Untrue Blood

The Protestant Reformation, which began as a broad protest against corruption and the fixation on rituals and sacred objects in the Catholic Church, soon gave rise to a series of more finely tuned doctrinal disputes. One point of fierce contention was “transubstantiation,” the longstanding Catholic doctrine that the holy wafer and wine were miraculously and literally transformed into Christ’s body and blood during the Eucharist ceremony. Leading Protestants in the German lands came to believe that the transformation of the bread and wine was more symbolic than real. In the course of the 16th century, this and other heresies began to spread into Poland, where Protestantism was beginning to make significant inroads. The poet Mikołaj Rej, Magda Teter tells us in Sinners on Trial, went so far as to publicly ridicule the entire idea of transubstantiation: “If I am to believe that here is the whole Christ,” he quipped at the Council in Cracow in 1570, “I am afraid I might choke on his shin.”

Rej doesn’t seem to have paid a price for his wisecrack. Protestants of his stature were more or less tolerated in early modern Poland-Lithuania, and punishments and executions were usually reserved for Christians who went so far as to steal or make improper use of the consecrated wafer. Needless to say, Jews needed only to be accused of such crimes to suffer comparable treatment.

Not quite as old or as infamous as the related charge of ritual murder, the accusation of host desecration can be traced only as far back as late-13th-century France. But from that time on, Jews in Western Europe were periodically accused and convicted of torturing Eucharist wafers by stabbing them with knives and causing them, miraculously, to bleed. In post-Reformation Poland, host desecration trials occurred about once every decade. There was, of course, a common idea behind ritual murder and host desecration accusations: whether drawing blood from an innocent Christian child or from a holy wafer, Jews were imagined to be re-enacting the crucifixion.

Historians have puzzled over the resilience of blood libels, which were at once so deadly and so purely fantastical. Some have argued that the accusations were intended to shore up shaky Christian belief by creating new myths, saints, and pilgrimage sites at Jewish expense. Others have seen them as a means of undermining Jewish prosperity. Still others have traced specific libels to local politics, the most notorious and unusual example being the 1759 Lvov disputation in which the messianic pretender Jacob Frank and his followers—in retaliation for persecution suffered at the hands of fellow Jews—cynically proposed to prove the veracity of Jewish ritual murder.

In her new study of accusations of Jewish sacrilege in post-Reformation Poland, Magda Teter argues that host desecration accusations in that country may actually have had less to do with Jews themselves than with intra-Christian contests. If Jewish tormentors could be shown to have caused the host to bleed, she explains, Catholics would have an answer to the mockery of Protestants like Rej. This claim is not new. In her 1995 book Czarna Legenda Żydów (The Black Legend About Jews) Polish scholar Hanna Węgrzynek concluded that host desecration accusations were “not only directed against Jews but also against Protestants, as unbelievers and traitors who were cooperating with Christ’s killers. The miracles accompanying the alleged desecrations were another argument proving the real presence of the body and blood of Christ in the consecrated host, one of the most important dogmas rejected by the Protestants.” But if Teter is not the first to take research in this direction, she has considerably advanced the argument by retelling the tale of Polish host desecration accusations with a graceful narrative and rich new detail.

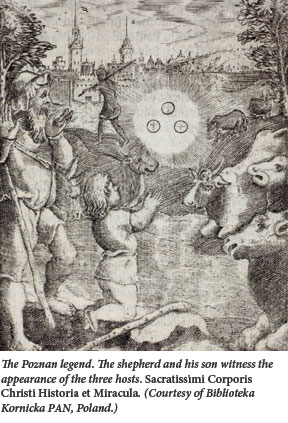

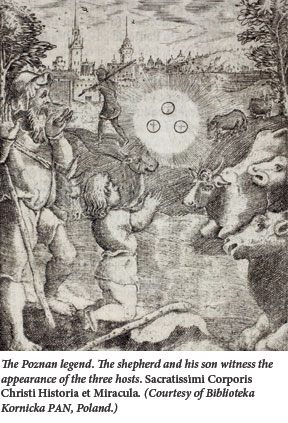

As Teter makes clear, accusations of host desecration against Jews surfaced in Poland only in the 16th century, when Protestantism first arrived in the country, and diminished in the mid-17th century when the Protestant threat to Polish Catholicism became significantly smaller. There is, to be sure, an account of the construction in 1401 of Poznan’s Corpus Christi church in a remote marshland where a shepherd is reported to have stumbled across some hosts that a group of Jews had previously tortured and tried to bury. Upon arriving at the scene of the crime, he noticed butterflies flying out of the spot, cattle kneeling all around, and three floating hosts. However, as Teter observes, “none of the earliest documents on the founding of the Corpus Christi church mentioned host desecration by Jews.“ The church’s foundation legend apparently was transformed into an anti-Jewish tale only much later, when Polish Protestantism was in full swing.

As Teter makes clear, accusations of host desecration against Jews surfaced in Poland only in the 16th century, when Protestantism first arrived in the country, and diminished in the mid-17th century when the Protestant threat to Polish Catholicism became significantly smaller. There is, to be sure, an account of the construction in 1401 of Poznan’s Corpus Christi church in a remote marshland where a shepherd is reported to have stumbled across some hosts that a group of Jews had previously tortured and tried to bury. Upon arriving at the scene of the crime, he noticed butterflies flying out of the spot, cattle kneeling all around, and three floating hosts. However, as Teter observes, “none of the earliest documents on the founding of the Corpus Christi church mentioned host desecration by Jews.“ The church’s foundation legend apparently was transformed into an anti-Jewish tale only much later, when Polish Protestantism was in full swing.

Teter demonstrates the linkage between the Protestant-Catholic struggle and anti-Jewish accusations most effectively in her account of the first documented trial for host desecration in Poland. In the spring of 1556, in the town of Sochaczew, a Christian servant named Dorota Lazecka confessed to stealing the holy wafer from a church in a village near Sochaczew and bringing it to her Jewish employer, Bieszko Szkolnik, who together with several accomplices allegedly proceeded to stab it and collect the wafer’s blood. Under torture, Szkolnik said that he did not know why the Jews required this blood, “but ‘had learned from Jewish leaders’ that it was needed during circumcision to spread over the wound.” He also confessed to the killing of a Christian boy. All those implicated in the crime—Dorota and five Jewish innocents—were subsequently burned at the stake.

That same spring, only 25 kilometers away, the papal nuncio, Bishop Luigi Lippomano of Verona, was deeply involved in a mission to “heal” a land that had, in the words of the Pope, “been infected by the heretical depravity.” From March to May of 1556, Lippomano’s ecclesiastical court was busy investigating reports that two Polish bishops were “polluted with heretical blemish and publicly nurtured among themselves heretical men.” The worst evidence revealed one of the bishops’ disbelief in the doctrine of transubstantiation.

According to one account, on Good Friday, after giving Communion to some students (scholars) “as is customary,” the bishop called on one of them and asked: “Lo, you! What do you believe you take in the Communion?” When the student responded, “The true and holy Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who was born of the blessed Virgin,” the bishop apparently exclaimed: “No, no; you believe the wrong thing (tu credis male). You have taken a token of [his] body, not the actual body.”

According to one account, on Good Friday, after giving Communion to some students (scholars) “as is customary,” the bishop called on one of them and asked: “Lo, you! What do you believe you take in the Communion?” When the student responded, “The true and holy Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who was born of the blessed Virgin,” the bishop apparently exclaimed: “No, no; you believe the wrong thing (tu credis male). You have taken a token of [his] body, not the actual body.”

News of Lippomano’s high-profile investigation must have spread quickly, Teter concludes, despite his efforts to keep things secret. “Travelers, merchants, and probably also vagabonds” undoubtedly carried word of the extraordinary activities of the papal nuncio to nearby Lowicz and Sochaczew. To Teter, it does not seem at all coincidental that Dorota was arrested in Sochaczew only a week after Lippomano sent his first report on the investigation to Pope Paul IV.

News of the Sochaczew trial, in turn, reached Lippomano quickly, and he “embraced it enthusiastically.” For “not only did it support his long struggle to affirm the dogma of transubstantiation, but it allowed him to push for his broader agenda—to fight heresy and to assert ecclesiastical authority over cases of religious doctrine.” Interestingly enough, the aggressive publicity campaign after the executions of Dorota and the five Jews prompted Protestants to react, accusing Catholics of trying to scare people with “made up false miracles.”

By developing Hanna Węgrzynek’s thesis so elaborately, Teter demonstrates that theological disputes are rarely only theological disputes, and that inter-ethnic conflicts are rarely only inter-ethnic conflicts. The struggle for power and authority seems always to intrude. Moreover, sometimes it is interethnic cooperation that gives rise to misunderstandings. For example, Teter recognizes that the use of Jews as ‘fences’ by Christians who were trafficking in stolen sacred objects merged rather naturally into deadly accusations against Jews themselves, for “the step from the charge of robbery to a charge of host desecration was an easy one.”

Teter has perhaps not been sufficiently critical of the Catholic perpetrators of host desecration accusations. At times, her book strays into psychoanalysis, interpreting the libels as reflecting “the Catholic Church’s profound anxiety about its identity and power after the threat of the Protestant Reformation.” It is worth remembering that, however much it might have lacked theological self-confidence, the Catholic Church remained the sole state-sanctioned religious institution in Poland throughout the Reformation. Its displaced aggression onto Jews sometimes resulted in state-sanctioned murder.

The tragic absurdity of pre-modern Christian fantasies about extraordinary Jewish power, in this case the power to kill an embodiment of God, is that the trials and executions they inspired exposed, time and again, a reality of powerlessness.

Suggested Reading

The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

After he visited the odd talmudic genius, Bialik said that “two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.”

The Danish Prince and the Israelite Preacher

Hamlet, Shakespeare’s most peculiar tragedy, echoes one of the most peculiar books in the Hebrew Bible, Ecclesiastes. It also helps us understand its wisdom.

Could It Have Happened Here? The Implausible Plotting of The Plot Against America

Was America in 1940 primed for an antisemitic leader, as Roth and his adapters would have us believe?

A Murder in Miropol

Lower simply shows us what she saw and lets us feel the weight of it; it's almost too much to bear.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In