The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

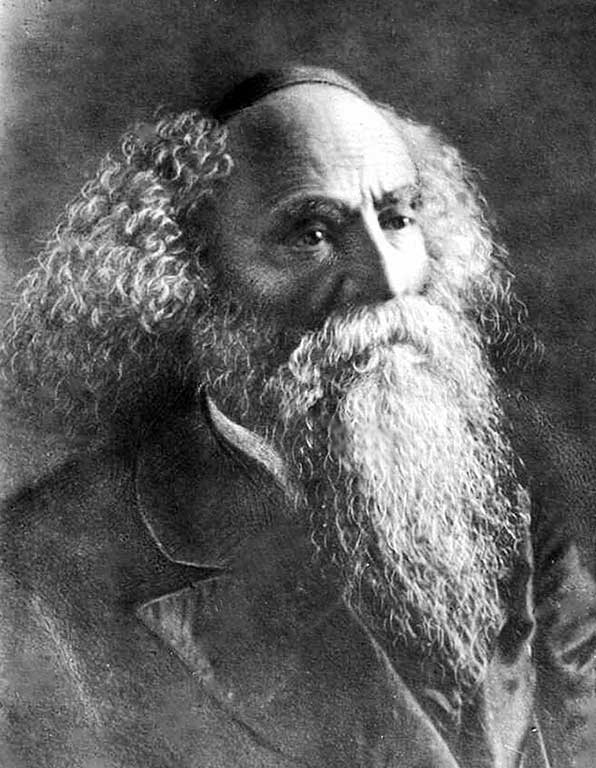

Ask a yeshiva student who the greatest talmudic genius of the 20th-century was and odds are he will answer “the Rogochover.” Ask him who was the most unusual talmudic genius of that time, and you will probably get the same answer. The Rogochover was Rabbi Joseph Rozin (1858–1936), rabbi of the Hasidic community of Dvinsk. Yet as with many rabbinic greats, his birth name has been supplanted by a resonant phrase—in this case not the name of his famous book, but rather the city of his birth.

The Rogochover’s genius and unconventionality are immediately evident to anyone who peruses his writings, which are collectively known under the title Tzofnat Pane’ach (the biblical Joseph’s Egyptian name), but there is hardly anyone who does more than peruse them, as they are extraordinarily terse and difficult. Take his responsa, for instance. While responsa generally follow a pattern in which a question is posed and a halakhic response is formulated by interpreting key texts, with the Rogochover almost all you get is “see this” and a lengthy list of rabbinic citations. He wrote many thousands of such letters to scholars around the world. Such responsa have never been written by anyone else, indeed one often needs to be a significant talmudic scholar to even begin to understand how all these references relate to the question. It is said that the Rogochover, who found it hard to respect any of his lesser contemporaries, once sent such a letter to a less-than-stellar contemporary. Curiously, the references did not seem to have anything to do with the points raised by his correspondent—until someone pointed out that all of the sources referred to an am ha-aretz (an “ignoramus,” in current rabbinic usage).

(Widener Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Rogochover’s complete originality and independence as a legal thinker are striking. Take the question of the halakhic standing of civil marriage, which is one of the major rabbinic disputes of the 20th-century (a dispute that was later extended to the status of Reform and Conservative marriage). Does a non-halakhic marriage create a marital bond that requires a halakhic divorce (a get) to dissolve the union? While halakhic authorities lined up on opposite sides of the dispute, the Rogochover charted a unique path. In brief, he argued that the proper question is not whether or not a get is required, but rather what kind of get is necessary. The Rogochover held that the origin of the non-halakhic marital bond is in the pre-Sinai Noahide code that also recognizes marriage. Lacking a halakhic marriage, a couple with a civil marriage is married according to the Noahide code, and for Jews this status can only be ended with a get, which is written differently than a typical get.

Another less consequential, but characteristically original, idea of the Rogochover’s is with regard to the blessing one recites when embarking on a potentially dangerous journey (tefilat ha-derekh). The question was raised if one should recite this for airplane travel. For most rabbis this was not a hard question: If one recites this blessing while traveling even a short distance outside the city, then certainly one should recite it while flying hundreds of miles. The Rogochover approached this question from “left field,” or rather from an apparently unrelated talmudic passage (Hullin, 139b), which discusses the commandment to send away a mother bird before taking its young (or eggs). This discussion focuses on the significance of the word derekh in the biblical verse recording this obligation: “If a bird’s nest chance to be before thee in the way (derekh)” (Deut. 22:6). Because the word derekh is used elsewhere in the Bible with reference to the sea (Isaiah 43:16), the Talmud derives the rule that one who finds a nest at sea must send the mother bird away before taking the young. However, the Talmud also concludes that if you find a bird’s nest in the air (for example, being carried by a flying bird), there is no such obligation, as the word derekh is not used with reference to the sky. The Rogochover concludes that one traveling in an airplane does not recite tefilat ha-derekh, as a route through the sky is not considered a derekh.

The Rogochover’s genius was tied to his unconventionality. Whether it was his unrabbinically long hair (no one knows for sure why he allowed his hair to grow so long, and there is no evidence that he was any sort of Nazirite, as is sometimes claimed), or the fact that he broke with rabbinic convention by refusing to deal with post-medieval rabbinic sources, the Rogochover was certainly different than his contemporaries. While other 19th– and 20th-century rabbis regarded the Shulchan Arukh as the standard code of Jewish law and the first place to look when one had a halakhic question, the Rogochover had little use for it. He made legal decisions based on the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, Maimonides, and other medieval sources when necessary.

In fact, it is questionable whether the Rogochover’s behavior can always be regarded as halakhic. I refer to the fact that he famously studied Torah on both Tisha b’Av and when he was in mourning, behavior that is against accepted Jewish law. When asked about this, the Rogochover is said to have replied that he was happy to be punished for the study of Torah, because the Torah was worth it. Adding to the legend of the Rogochover is how he treated his rabbinic contemporaries and earlier rabbinic greats. Such outstanding figures as Rabbi Moses Sofer and Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Spektor could be pushed aside with the wave of a hand. As shown in the document published here, even the Vilna Gaon did not escape his tongue.

The Rogochover’s special love for Maimonides, who in his eyes stood above all other medieval greats, is not only seen in his halakhic writings or in his volumes of commentary on Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah. Unusual among his contemporaries, the Rogochover also intensively studied Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed, and a number of his notes on it survive. (In these notes he particularly attacked the 13th-century commentator Moses of Narbonne, whom he regarded as nothing less than a heretic.) A number of the philosophical expressions found in the Guide were applied by him in an original fashion to halakhic texts.

After the Rogochover died in 1936, his daughter Rachel Citron returned to Latvia to assist his student Yisroel Alter Safern-Fuchs in collecting and saving many of the Rogochover’s manuscripts, which they photographed and sent to New York. Some of this material was later published by Rabbi Menachem Kasher, but most of it still remains in manuscript. Citron and Safern-Fuchs were murdered in the Holocaust.

On December 11, 1933 the New York Yiddish paper Der morgen-zhurnal published a rare profile and interview with the Rogochover by its Riga correspondent. As far as I know, this interview has never been discussed in the scholarly literature. I thank Shimon Szimonowitz for producing an initial translation, which I in turn revised.

A Discussion with the Rogochover Gaon about Wordly Matters

From Our Riga Correspondent M. Gurtz

The Rogochover Gaon lives in the Latvian provincial city of Dvinsk. Occasionally, the Rogochover travels to Riga either because of his poor health, to preside over an important din Torah, or for some other reason.

On these occasions, when the Rogochover comes to Riga, he is friendly with the people and it is actually possible to converse with him. In Dvinsk this is impossible since this gaon, by nature, does not enjoy visiting or exchanging idle talk. Simply put, the Gaon is not a people’s person. He does not have regard for people. He holds of no one. He holds only of one thing—learning Torah. The Gaon is so preoccupied with Torah study, that he does not even have time to be frum . . . [The ellipses here and elsewhere are to be found in the original.] His prayers take only a few minutes. He does not even put back his tefillin. It would be a sin to waste so much time—he needs to learn!

One must know that the Rogochover is not only considered a gaon in our ignorant times. He would have been considered the same gaon in previous generations, when the Torah was still considered by Jews to be precious merchandise.

The best characterization of the Rogochover was made by H. N. Bialik. The Rogochover—Bialik holds—is the most brilliant talmudist whom he had the opportunity of meeting:

From one Rogochover one can carve out two Einsteins. The Rogochover is nowadays something unique, a rare mechanism of which only one exists, one of a kind. The Rogochover needs to be considered a great spiritual national treasure.

If we were to translate the enormous talmudic knowledge of the Rogochover Gaon into scientific knowledge, it would enrich the sciences with great new works. If we were to draw out all of the Rogochover’s talmudic knowledge we could then set up an entire cultural history. In short, this is the opinion held by the greatest Jewish poet about the Rogochover: Two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.

It is interesting and also fascinating to converse with such a Jew. Of course, it is even more so when one is able to draw such a Jew into a discussion about contemporary issues—Jewish suffering, Hitlerism and other problems.

It is true that while the Rogochover is extraordinarily clever in talmudic subjects, in worldly matters he is not the greatest specialist. Nevertheless, it is still interesting [to hear] his opinion about contemporary worldly matters. One must bear in mind that in order to speak with the Rogochover, even about worldly matters, one must be a lamdan. In the course of the most basic conversation, the Gaon weaves in many Toseftas, Mechiltas, Sifras, and other books, leaving one dizzy. In the eyes of the Gaon, every issue in life can be solved with an “open” Yerushalmi . . .

To present a discussion that was held with the Rogochover, one needs to peel away all the talmudic texts and commentaries [he quotes] in order to convey the main point. We will make an attempt at that. Let us hear what he, the greatest Jewish gaon of our times, says about the question that we are all agonizing over so much.

“The Jewish situation is not good right now”—says the Gaon—“a new war is unavoidable. I just do not see another way . . . When all [nations] are so divided and against one another. . . On one side there is Russia, Italy, and Japan, and on the other side all the others. Today there are troubles in Austria . . . and all because of Germany. This is no small matter!” And the Gaon lectures about Germany, cites many Gemaras, and reveals that today’s Germans are not real Aryans.

Office, Israel.)

“The Rambam says in his commentary on the Mishnah”—says the Rogochover—“that the name Germany is derived from the Hebrew word gerem—a bone. The Germans are hard like a bone and therefore their wild actions should come as no surprise.” “But in truth”—concludes the Gaon—“today’s Germans, who inhabit Germany, are not real Aryans. The real Germans immigrated to England hundreds of years ago, and today’s inhabitants of Germany are the ancient Slovaks and Swabians . . . The English are to blame for the entire current situation . . . It is better not to talk . . .”—The Gaon makes a motion with his hand and moves on to other subjects.

I do not let the Gaon digress and I ask him a foolish question: Rebbe, what will happen in the end? When will we be redeemed? Jewish suffering is too much to bear! Hitler . . .

The Gaon gets angry: “It is true that it is not a good situation for us, but when did we have it better? Now the oppressor is Hitler, once it was Haman, Pharaoh, Torquemada, Purishkevich—only the names change, but the suffering remains the same. It is possible that the troubles in the past were greater. When we compare the entire Jewish situation in the world to certain eras in Jewish history, it will emerge that Jews are now doing much better than in certain difficult eras of the past. There is no reason to despair.”

This is basically the opinion of the Rogochover if we were to strip his words of all the multiple Gemaras and commentaries [he cited]. Maybe he is correct . . . He just freed himself of [the topic of] politics and he goes back into his domain [comfort zone].

“There is not even one person”—says the Rogochover—“who can understand how important a piece of Gemara is. Even in Russia where there are many Jews”—says the Rabbi—“and where so many famous rabbis live, they also do not have the basic understanding of a passage in the Gemara.”

What does that mean, everyone is wondering? In Russia it is now forbidden to study [Torah]. Who in Russia is now learning Torah?

The Gaon becomes angry. “In Russia they learn Torah now just like before. There are those who learn and those who do not. It was always like that. Nine years ago, I was in Russia, and I learned as much as I wanted. No one disturbed me. The Jews whom I was with also studied undisturbed. It depends on where you are . . .”

“But Judaism”—someone interjects with a comment—“is going under in Soviet Russia, how can you say this?!”

The Gaon gets a bit angry and mocks the questioner. “Since when did you start to worry so much about Judaism, about religiosity? Have you no other worries? Since I remember, they are always saying that Judaism is going under, and praise the Almighty! . . . ”

We go back to the original discussion, in which the Gaon had said that no one knows how to [properly] study a piece of Gemara. What does this mean? What about the Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Akiva Eiger and the other gedolim?

The Rogochover waves his hand [in a dismissive way] and says: “The Vilna Gaon had all-encompassing knowledge, he took everything in. But that is not all [there is to knowing Gemara]. In a shtetl near me lived a melamed, a small rebbele [teacher of children]. He dressed with a torn hat and he knew how to learn much better than the Vilna Gaon . . . a thousand times more! You see, the Rambam knew how to learn, he truly knew how to learn well.”

And for that reason, the Rogochover Gaon considers the Rambam to be his teacher . . .

The Rebbetzin, who accompanied the Gaon on his way, lets the people know that the Rabbi is not allowed to talk so much. It is already two o’clock in the afternoon and the Rabbi still has not eaten breakfast. The people finally take leave of the Gaon.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Some Calming Words

Hillel Halkin shouldn’t be so worried. Democracy is still alive and kicking in Israel. The Israelis who didn’t vote like him aren’t stupid. They’re no less wise, humanitarian, and upright…

Ruby Sees Red

"I’m still trying to wake up from this nightmare. I walk in the streets. I see parents with babies. I can’t look. I walk in Riverside Park, I see an older man hugging his granddaughter, and I almost start crying. We have been forced back into Jewish history, into the bloody raw part of Jewish history."

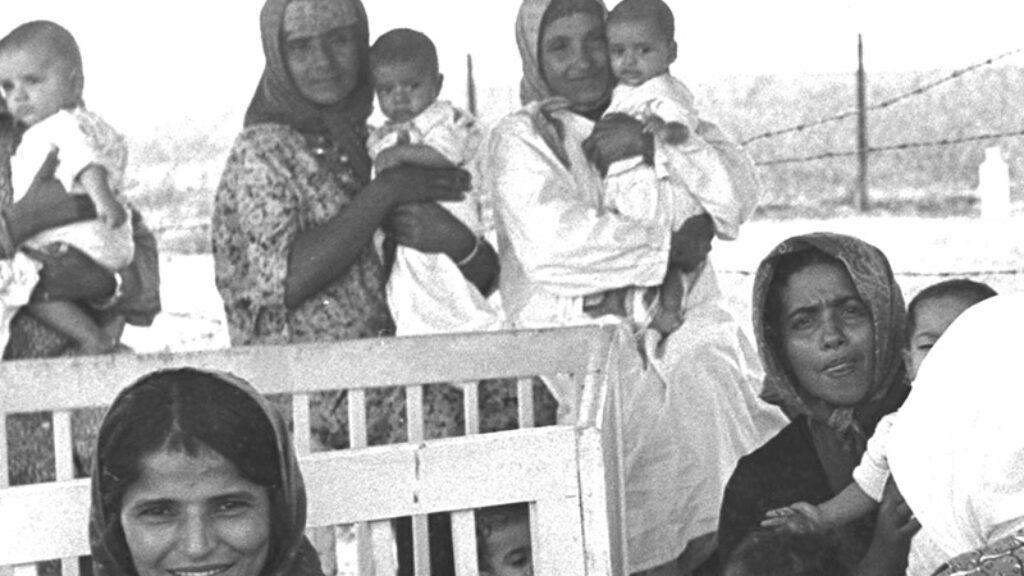

Kidnapping History

Did the Ashkenazi elite of the early State of Israel conspire to systematically kidnap Yemenite Jewish children?

A Journey Through French Anti-Semitism

There is a problem with the inevitable reflexive warnings after every vicious attack not to slip into Islamophobia. A short personal history of how France got here.

kaganovitch

In all likelihood, the Rogatchever's dismissal of the Vilna Gaon was motivated by traditional Chabadsker antipathy to the Gaon as leader of the misnagdim. In general Chabad retained it's pugnacious attitude towards misnagdim far longer than other strands of chassidus. Indeed the polemic with misnagdim exists up until the present day in Chabad. When the Alter Rebbe was released from prison, he was released into the custody of a sort of court Jew, Nota Notkin from Shklov who was permitted to have residence in St Petersburg. He was there for a few hours before chassidim could arrange to pick him up and take back to Liozna. I have heard many times from Ana"sh friends the trope " Der Alter Rebbe hut gehat mehr tzaar fun di por sho'oh by der misnagid Notkin, vi in der gantze tzeyt in tfisse beym Czar". --"The Alter Rebbe suffered more in these few hours by the misnagid Notkin than he suffered in the Czar's prison". Combine this attitude with the traditional Chabad pungency of expression and you get the Rogatchever's statement. It's (ceteris paribus) not very different from what is said in Chabad about (I think)the Smargoner gaon. When Reb Chaim Brisker's daughter was suggested as a shidduch for one of his sons, The Smargoner sent two of his daughters to Brisk to make the young girl and her family's aquaintance and report back. When they returned they allegedly said "Tateh, Deyn asher yotzar is mehr vi zeyr krias shma"

daized79

Well I guess he should've stuck to Talmud. Oy.