Distant Cousins

Reading novels published in the last year by some of America’s best Jewish writers, I found myself struck by a recurring character—Israel. That Jonathan Safran Foer’s Here I Am and Joshua Cohen’s Moving Kings both feature Israel and Israelis as important plot devices might have been a coincidence. But then this fall came Nathan Englander’s Dinner at the Center of the Earth and Nicole Krauss’s Forest Dark, both of which are set mostly in Israel. Something’s going on.

I came at these novels as someone the same age as the authors (40-ish) who left North America at 17 and has been living and writing in Israel since then. That might explain my sensitivity to this shift in American Jewish fiction. (I should also mention that I know Foer and Krauss, and that Forest Dark has a passing reference to an Israeli journalist named “Matti Friedman.”) But I don’t think anyone reading these books could miss their distance from the brash and rooted tone of “I am an American, Chicago-born.” The center seems to have moved.

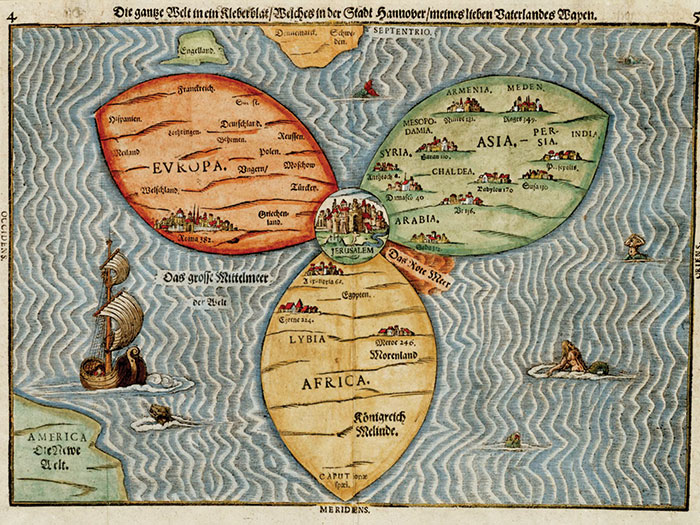

The Israel of each of these novelists is different, of course, but there are similarities. Two recount watching an Israeli war on TV from America and the strong emotions this elicits; two make reference to King David; two have hamsa keychains; two have the Mossad; all have soldiers; and all use a little Hebrew. Perhaps most tellingly, two feature American characters with Israeli second cousins—at first Jews in America and Israel were siblings divided by European wars, then first cousins, but now they’re only second cousins, a generational fact that might explain the fraying connection as much as anything else. None of these novels is fully at home in Israel—they’re more like Mars orbiters than rovers. They’re not permanently on the ground. But they have entered the gravitational pull of this place, which makes it worth trying to figure out what, exactly, that pull is.

Saul Bellow once said that for moral critics the Jewish state was becoming what the Alps are for skiers. To see how prophetic this remark turns out to have been, the reader need go no further than the recent collection of essays by writers who condemned the occupation of the West Bank after going on a little moral ski trip led by two prominent American Jewish novelists, Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman. None of the four authors here are up to anything as simplistic as that project (which I reviewed in the Washington Post), but moral dilemmas are certainly part of the draw. Englander’s Dinner at the Center of the Earth, for example, which is about an American Jew who becomes a Mossad spy before going off the rails, has two characters set out the positions for and against house demolitions. “Giving five-minute warnings to old women who never race out the door with anything but their olive oil and a picture of Arafat? It’s pitiful.” “How else do you punish someone who’s already gone? It’s a deterrent.” Elsewhere, there is a similar back-and-forth about bombing terrorists amid a civilian population, something the main character enables and regrets: “What we just did—it’s not what I signed up for.”

In all four novels Israel is the scene of strange and exciting events, if not outright enchantment, but the idea that magic is possible here is most present in Krauss’s Forest Dark. (Home, on the other hand, is where the novels set jobs, divorces, affairs, and bar mitzvahs.) Krauss’s narrator is a writer who has come unmoored in the United States and finds herself in Israel, which is evoked in descriptions of the Mediterranean, the warm and prickly people, the charmless concrete block of the Tel Aviv Hilton, and the smell of hot cat piss on the street—but also an Israel with the supernatural qualities suggested in some of the great stories set here, like the one in Kings where the prophet Elijah dramatically departs this earth without dying, or the one where Jesus dies, then comes back, and then leaves again, but is still not dead. In Forest Dark a departed European writer might live resurrected as a humble Israeli gardener, or an aging New Yorker might take a taxi to the Negev and vanish.

Many of the characters in these novels turn to Israel to shore up American lives that feel short on meaning, even if we’re not meant to take that turn entirely seriously. At the end of Foer’s Here I Am, in which an American family falls apart as Israel is struck by catastrophe and invaded, his main character gathers his courage and heads off to join the war. Entering a Long Island airport to be vetted along with other American Jewish volunteers singing “Jerusalem of Gold,” he reflects, “I had written books and screenplays my entire life, but it was the first time I’d felt like a character inside one—that the scale of my tchotchke existence, the drama of living, finally befitted the privilege of being alive.”

In Cohen’s Moving Kings, David King brings over an Israeli relative, a young military veteran, to work in his New York moving and storage company and muses that there’s something about Israel that is linked to immortality. “If he’d stay in touch with Israel,” King says of himself after a heart attack focusses his thinking, “if he’d maintain with Israel, certain responsibilities would devolve on the living after his demise. He was almost sure of it, he almost said it aloud: who among the living was going to shovel dirt in his grave or say a kaddish? His daughter?”

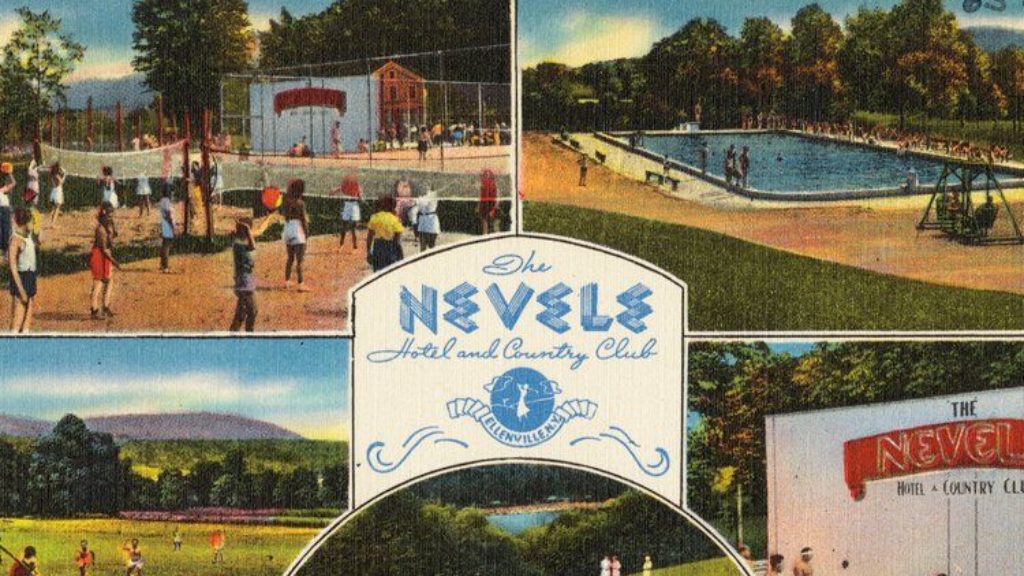

Jewish American writers of a few decades ago might have poked around the strange Jewish country in the Middle East, but they knew that the real literary action for them was back home. The novelists of 2017 don’t seem so sure. The immigrant fires of writers who once hit America like shtetl-launched ICBMs are now too cold to even toast a marshmallow. If you’re not a recent arrival from the Soviet Union, you’re not likely to have funny mannerisms, an ethnic chip on your shoulder, or much interesting history of your own. Yiddish nostalgia is stale, and with everyone in the suburbs, there is no American Jewish street. The broader American culture seems to offer little cohesion for a writer to either embrace or rebel against. So where do you go? As Shaul Tchernichovsky wrote in Berlin in the twilight of Jewish Europe a century ago, “They say there’s a country, a sun-drunk country…”

And so there is—a country that seems to have hit its cultural stride, having recently struck some reservoir of distinctly Jewish fuel, turning into a blend of Beirut, St. Petersburg, and Palo Alto, but mainly turning into itself. It’s a place that’s messed up and revved up and moving, one that feels so different from the American Jewish world not just because it’s Middle Eastern, and not just because it’s endangered, but because it’s alive.

Suggested Reading

Do Jews Count?

I would never have said this ten years ago, or even five years ago, but there apparently comes a time in the lives of those who write about Jewish identity when they have to decide whether to write about . . . it.

“I Am Talking to You Like King Solomon”

Saul Bellow once called Nabokov a “cold narcissist.” His letters to his wife, Véra, decisively dispel that common misconception.

Complicated Community: A Conversation with a Jewish Chavista

What happens to a Jewish supporter of Hugo Chavez when the revolution descends into chaos?

The Home Front

Eating very long breakfasts, lunches, and dinners with dozens of aging members of the Greatest Generation was the best part of Arkush's teaching experience.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In