“I Am Talking to You Like King Solomon”

“Most of my works have been dedicated to my wife and her picture has often been reproduced by some mysterious means of reflected color in the inner mirrors of my books,” Vladimir Nabokov said in one of his carefully wrought late-life interviews. Theirs was an artistic marriage, life and text conjoined. Arcing over two continents and several languages, the double story of Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) and Véra Nabokov (1902–1991) is both old fur hat and unworn fedora. Brian Boyd documented aspects of their marriage in his two-volume biography of Nabokov. Stacy Schiff told a version of the story of Véra Slonim’s transformation into Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov in her 2000 biography. In this long-anticipated volume, lovingly edited and translated by Boyd and Olga Voronina, we get a first-hand look at the marriage—at least from one angle. Some time in the late 1960s or early 1970s Véra destroyed virtually all of her letters to Vladimir.

Saul Bellow once called Nabokov a “cold narcissist,” and Letters to Véra decisively dispels that common misconception. In these letters, Nabokov is passionate and vulnerable; chivalrous and (sometimes) inconstant; a man of his time and one ahead of the historical curve. These are, above all, love letters, first for Véra alone, later for Véra and their son, Dmitri. Throughout, Vladimir writes to Véra with the flame of a young poet and the sophistication of a verbal conjuror. Here’s 24-year-old Vladimir in Prague writing to almost-22-year-old Véra in Berlin, on the eve of 1924: “I love you very much. Love you in a bad way (don’t be angry, my happiness). Love you in a good way. Love your teeth.” And here he is in April 1937, writing from Paris to his wife in Berlin:

I dreamt of you this night. I saw you with some kind of hallucinatory clarity, and, all morning long, have been going around in a sort of cloud of tenderness for you. I felt your hands, your lips, hair, everything . . .

Finally, this is Nabokov writing to Véra on April 10, 1970, one of the rare times they were apart during the last decades of their marriage: “My gold-voiced angel, (can’t get out of the habit of these endearments).”

Elegant and fearless, with her coiffed silver hair and regal bearing, with a pistol sometimes concealed in her handbag, in another life Véra Slonim might have become a commissar of the arts or a premier of Israel. But she had only one domain to guard and represent to the world, Vladimir Nabokov’s kingdom. As early as August 24, 1924, eight months before they were married, Vladimir tried on a Jewish crown as he wrote to Véra: “You understand my every thought,—and my every hour is full of your presence—and I am all a song about you . . . See, I am talking to you like King Solomon.”

Véra’s maiden name bespeaks her ancestors’ origins in the town of Słonim, formerly in Poland and now in Belarus, also the birthplace of the Slonimer Hasidic dynasty. Both of them born in the Pale and native speakers of Yiddish, Véra’s acculturated parents had seen most of the social and professional opportunities they had imagined for themselves and their children taken away in the late 1880s. Russian culture remained a sanctuary for the family of Evsey Slonim, a graduate of St. Petersburg University who left the legal profession following the 1889 imperial ukase barring Jews from practicing law. The Slonim sisters enjoyed a first-rate European upbringing in St. Petersburg and, as young émigrées in the early 1920s Berlin, felt no less European than did other educated “Russians” in exile. Her sisters would also marry or form public unions with non-Jews. Her older sister Helena Massalsky converted to Catholicism, married a prince, and barely escaped from Nazi Germany with their young child. Véra’s letter to Helena, dated December 4, 1959, offers much insight into her own Jewish identity:

Does Michaël [Helena’s son] know that you are Jewish, and that consequently he is half-Jewish himself? . . . Mind you, my question has nothing to do with your Catholicism, or the religious education you may have given your son. . . . I must admit that if M. does not know who he is there would be no sense in my coming to see you, since for me no relationship would be possible unless based on complete truth and sincerity.

Véra’s unapologetic line was drawn on loyalties of memory, blood, and spirit.

Not only in the Soviet 1920s but also in the Russian émigré milieu, in which Véra and Vladimir discovered each other in 1923 Berlin, the social gap between Jews and non-Jews had been closing. Nonetheless, even Russians known for their philo-Semitism voiced private exasperation at marriages between Russian aristocrats and young Jewish women. Ivan Bunin, one of young Nabokov’s literary masters, had himself been married to a half-Jewish woman in Odessa and would shelter Jews during the occupation of France. Yet, on April 7, 1922 Bunin noted in his diary:

[Prince Vladimir Argutinsky-Dolgorukov] walked me home and on the way told me about Prince Golitsyn, who in Berlin married a Jewess—for 75 thousand marks. These marriages are getting ever more frequent, Jewesses becoming countesses, princesses—finishing us off, purchasing us up.

Bunin’s irate comment anticipated other Russian émigrés’ hushed puzzlement over Nabokov’s choice of bride.

Nabokov’s grandfather Dmitri N. Nabokov had been minister of justice under two tsars. In terms of probabilities, a scion of such a wealthy aristocratic Russian family was unlikely to marry a Jewish woman. Nabokov’s father, a liberal statesman and champion of Jewish legal equality, was killed by an ultra-rightist assassin in Berlin in 1922. “[My father] very much shared his own father’s very strong opposition to anti-Semitism, was close to Jewish culture in many ways—not typical for a young Russian man,” Nabokov’s son, Dmitri, told me in 2011. Stacy Schiff notes, “Nabokov’s mother . . . embraced Véra warmly. No discomfort whatever materialized.” Piercing the bubble of Russian aristocratic toleration, Nabokov’s grandmother (Maria, Baroness Korff) poignantly queried about the bride: “Of what religion is she?” Véra and Vladimir were married in a civil ceremony in Berlin on April 15, 1925.

After Nabokov’s death, Zinaida Shakhovskoy, who had been a great supporter of Nabokov’s work in the 1930s and once been related to him by marriage, published V poiskakh Nabokova (In Search of Nabokov), in which she charged Nabokov with abnegating Russia and his Russian friends. It was indeed an old canard (Russian bigots had called Nabokov a “half-Yid” in the 1930s). The book was, Shakhovskoy admitted, written “against Véra,” and it reignited the debate over Véra’s impact amongst Nabokov’s aging relatives and émigré colleagues. Nina Krivosheina, a member of the Resistance during the war, mixed reason and prejudice as she linked Nabokov’s “anticlericalism” with his marriage, writing to Shakhovskoy: “Following his marriage Nabokov became completely enjuivé,” that is “Jewified.” Nabokov’s sister Elena Sikorski sharply rebuked Shakhovskoy, who had been born a Russian princess, writing to her that Véra was “an aristocrat of the spirit, not of the name.”

Véra herself never shirked or apologized for her identity. In 1958, after an article in the New York Post described the Nabokovs as Russian aristocrats, Véra wrote to correct the paper: “In your article you describe me as an émigré of the Russian aristocratic class. I am very proud of my ancestry which actually is Jewish.” Seven years later when Bellow’s Herzog beat out Nabokov’s The Defense for the 1965 National Book Award she remarked: “I know many Jews, including my own family, and never saw anybody or anything even remotely like his [Bellow’s] Jews and his ‘Jewish’ atmosphere.”

Véra and Vladimir Nabokov became parents in 1934 while living in Nazi Germany, where the Nuremberg Laws would soon be passed. In a January 1939 letter to their sister Elena, Nabokov’s brother Sergei stressed young Dmitri’s “Jewish” looks: “Thank God that they got out of Germany. They would have had a difficult time, and right now it would be utterly ghastly.” With Nazi troops advancing, the Nabokovs departed from France in May 1940 on board the Champlain, chartered by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society to carry Jewish refugees. Nabokov always spoke of his first American years as happy, even his happiest. This was not because he had forgotten the horrors and people he left behind, and the first novel he wrote in America, Bend Sinister, depicted an intellectual living under a brutal “Communazi” regime. Nabokov’s American “happiness” was that of a Russian man who had managed to rescue the two Jews he loved the most, his wife, Véra, and son, Dmitri.

Shortly before his death, I asked Dmitri Nabokov in Montreux if his parents ever discussed religion with him.

We never had that problem, and neither did I. . . . For example . . . I sang on Fridays and I think on Saturdays at a wonderful . . . would it be Reform synagogue . . . in Boston. . . . So yes, it was never much of a problem.

In the late 1940s, while attending St. Mark’s School, Dmitri, who became a professional opera singer as an adult, sang in both a Protestant church and a synagogue. If he and his mother discussed Judaism, it was mostly in the context of liturgical music and literary culture: “I could ask her certain details, meanings of certain words, meanings of certain similes.”

One can see the way his marriage to a Jewish woman opened Nabokov’s eyes. In his longest pre-war novel, The Gift, the aristocratic protagonist, who is married to a half-Jewish woman, goes from professing vaguely liberal beliefs in the equality of all people to a “personal shame for listening silently to [anti-Semitic] rot.” Three decades later, in a letter to his former St. Petersburg classmate Samuel Rozoff, an Israeli architect, Nabokov wrote: “I have been with you with all my soul, deeply and anxiously, in the course of the latest events, and I triumph now, saluting the marvelous victory of Israel [in the Six-Day War].”

Letters to Véra is both a guide to Russian culture in exile and an atlas of Nabokov’s rising fame and acclaim. Vladimir often wrote Véra daily when they were apart, with the densest periods of letter-writing being in the summer of 1926, when Véra was under medical care in the Black Forest, and January–May 1937, when Nabokov was alone in Paris. After 1940, the maps of Nabokov’s American—and then Swiss—years are far more scantily represented—partly because Vladimir and Véra were rarely apart over their last four decades together. After February 1945 there’s a gap of almost nine years, and save for an occasional note, illuminated inscription, or improvised verse, Vladimir’s letters to Véra peter out in the 1960s, following Lolita’s stardom.

Reading these letters, one hears echoes or premonitions of pages in the novels and short stories. Olga Voronina compares a passage from a 1926 letter to the opening of Lolita. In fact even earlier, on August 18, 1924, Nabokov writes to his future wife:

I need so little: a bottle of ink, a speck of sun on the floor—and you; but the latter is not all that little, and fate, God, the seraphs know this perfectly well—and withhold and withhold . . .

Decades later, Humbert Humbert will speak of jealous “winged seraphs.” In their fragmented unity the missives collected in Letters to Véra amount to a deeply literary text in their own right. On January 22, 1936, Nabokov writes from Brussels: “My adorable love, all went well (true, my journey was somewhat marred by the torturous talkativeness of a tailor from Kovno who got so friendly he offered me a foot-long kosher sausage as a present).” In 1940, in Nabokov’s first English-language novel, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, the tailor from Kovno would become Mr. Silbermann, a Lithuanian Jew and the author’s helper.

There is one epistolary chapter, in which the fabric of this Jewish-Russian marriage comes close to being ripped. In the spring of 1937, Nabokov left Véra and three-year-old Dmitri in Nazi Berlin to try to establish a base for them in France, or, if possible, find a way to America or England from there. In Paris, he was embroiled in a love affair with Irina Guadanini, a Russian émigrée, all the while writing anxiously and guiltily to Véra about Russian literary life there. On May 1, 1937, he writes: “What a truly unpleasant gentleman Bunin is. He can more or less tolerate my muse, but he cannot forgive me my ‘lady admirers.’” It’s difficult to read some of these letters without a rancid aftertaste.

Two weeks earlier, on their 12th wedding anniversary, Nabokov had written:

My love, my love, how long since you stood in front of me in your prim little robe—my God!—and how much new there will be in my little one, and how many births (words, games, all kinds of little things) I’ve missed . . . Poor Ilf died, and somehow one thinks of separating Siamese twins. I love you, I love you.

Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov were Soviet writers, who co-authored their fabulously popular satirical novels until Ilf’s death dissolved the partnership. One cannot help but suspect that Nabokov was thinking of his own partnership with Véra. The Nabokovs’ marriage survived the trial of infidelity and separation. Marital discord, framed by the advent of World War II and the Shoah, seeped into Part 2 to The Gift, composed around 1940 and only recently published by Andrei Babikov. In the unfinished Part 2, the half-Jewish Zina and her husband Fyodor are living in Paris in the late 1930s; they are childless and poverty-stricken. Their marriage is strained; Fyodor sees a French prostitute. Zina dies in Paris, run over by a car—perhaps more of an authorial rescue from encroaching history than it is an authorial punishment.

Dozens of Jews appear as minor characters in the pages of Letters to Véra, but Nabokov seems to have been more likely to take up Jewish topics when writing to others, for instance his trusted friend, the Jewish-Russian writer Mark Aldanov. He was however quick to notice and report anti-Semitism to Véra. Thus writing from Paris in 1932 of a visit with the writer Boris Zaytsev and his wife: “They have tons of Jewish friends, but, at the same time, Zaytsev likes to savour, now and then, a Jewish accent. And overall, there is something a little off in them, some rather unpleasant little quirk.” Six years later, Zaytsev would write to Bunin that the émigré community was divided into “Jews who are crazy about [Nabokov]” and “Russians (and especially Orthodox Christians) who don’t like him.”

As a non-Jewish writer writing with much sensitivity about Jews, Nabokov was in a league of his own in Anglo-American fiction of the 1940s and 1950s. The figure of Jewish parents who lose or fear losing their sons had appeared in his Russian works and reappeared in his American works, from the story “Signs and Symbols” to the novel Pnin. Pnin is often thought of as an academic comedy, which, to some extent, it is, but it is also one of the first great post-Shoah novels. Nabokov endowed Timofey Pnin, a Russian émigré professor living in postwar America, with ceaseless memories of a Jewish first love, Mira Belochkin, who died in Buchenwald. Mira embodies Pnin’s brightest recollections of Russia and of love, and she helps him understand that memory, however painful, is an ethical imperative.

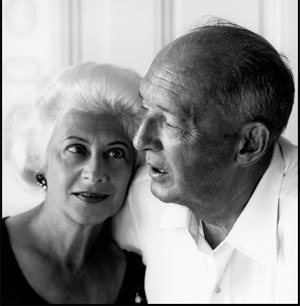

Véra loved her husband with a Russian idealism, a Jewish loyalty, and an American pragmatism. In a 1958 picture taken in Ithaca, New York by Carl Mydans, Professor Nabokov dictates to a tired-looking Véra as she works the typewriter like an organist. We see Vladimir reflected in a wall mirror. As Nabokov was to say later, Véra’s luminous image was constantly present in his texts. Following the escape to America, Véra remained Vladimir Nabokov’s muse as she also took charge of almost every aspect of his life and career. After his death in 1977 and until her own death in 1991, she curated his legacy—and Dmitri Nabokov took over his mother’s baton. When I spoke to Dmitri Nabokov in 2011, he said simply, “My mother did more for my father as a person and a writer than anyone else in the world could have.”

Suggested Reading

Sitting with Shylock on Yom Kippur

The poet Heinrich Heine imagined the merchant of Venice attending Neilah, the final service of Yom Kippur, but I find him earlier in the day, at Mincha, and we are listening together to the story of another Jew among Gentiles, bitter at being compelled to show mercy.

Shas: The Movie

If you think this Israeli election is raucous, travel back to 1984 and Shas's arrival on the political scene in the film The Unorthodox.

Strange Journey: A Response to Shmuel Trigano

Two historians challenge Shmuel Trigano’s analysis of anti-Semitic violence in France.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Stepan Bandera: A Rejoinder to Dovid Katz

Konstanty Gebert responds to Dovid Katz's critique.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In