When Eve Ate the Etrog: A Passage from Tsena-Urena

The commandment to recite the blessing over the lulav and the etrog on Sukkot can only be fulfilled with a fully intact fruit. If the etrog’s stem is broken off or missing, it is unfit for ritual use. But as soon as the holiday is over, the etrog is superfluous. It was once the custom for a pregnant woman to bite off the tip of the etrog after services on Hoshanah Rabbah.

This strange action is an outgrowth of an early modern Ashkenazic tradition about the pangs of childbirth. The earliest known source for both the tradition and the custom is in the popular Tsena-Urena, the famous Yiddish biblical commentary by Jacob ben Isaac Ashkenazi of Janov, which was especially popular among women, and as some title pages had it, “men who are like women,” in that they read Yiddish instead of Hebrew. The brief passage below includes the text of a Yiddish prayer, or tkhine, that the pregnant woman is instructed to recite based on Bahya ben Asher’s commentary to Genesis 3:6. Strikingly, it also describes the forbidden fruit that Adam and Eve ate as an apple, a medieval Christian notion with no source in rabbinic interpretation.

Rather than being a Yiddish translation of the Pentateuch, as is commonly assumed, Tsena-Urena is a commentary on the Pentateuch, the Haftarot, and the Five Scrolls. First published at the beginning of the seventeenth century, it has appeared in more than two hundred and twenty-five editions and is still in print. Unfortunately, nineteenth-century publishers abbreviated and sometimes censored the text, and more recent publishers have followed in their footsteps. The following passage is among those that were deleted in the later editions.

This excerpt is taken from what will be, when it is finished, the first complete and annotated English translation of the Tsena-Urena. It is based on the earliest extant edition (Basel/Hanau, 1622).

The tree was good for eating (Genesis 3:6). The tree was good to eat. Some sages say that it was a fig tree and therefore they ripped off leaves from a fig tree to cover their shame after they ate from the tree of knowledge. Their eyes were opened and they were ashamed to go naked. Others say that it was a grape vine and that she squeezed some grapes and gave him wine, red as blood, to drink. That is why the commandment of niddah was given to the women, from whom red blood flows (Genesis Rabbah 15:7). Others say that it was an etrog tree and that is why it is the custom for women to tear out the tip of the etrog on Hoshanah Rabbah. That is to say, they give money to charity because “charity saves from death” (Proverbs 10:2), and so that God should protect the child she is pregnant with. Since she did not eat from the apple, may the woman give birth to her child as easily as a hen lays an egg, without pain. The woman should say, “Lord of the universe, because Eve ate the apple, we women must suffer the terrible fate to die in childbirth. Had I been present there, I would not have derived any benefit from it, just as now I did not want to make the etrog ritually unfit.” It was used for the fulfillment of a commandment for seven days, but now on Hoshanah Rabbah, the commandment is ended. I am not quick to eat it, and just as I have little benefit from the tip, so did I have little benefit from the apple that you forbade.

The tree was good for eating (Genesis 3:6). The tree was good to eat. Some sages say that it was a fig tree and therefore they ripped off leaves from a fig tree to cover their shame after they ate from the tree of knowledge. Their eyes were opened and they were ashamed to go naked. Others say that it was a grape vine and that she squeezed some grapes and gave him wine, red as blood, to drink. That is why the commandment of niddah was given to the women, from whom red blood flows (Genesis Rabbah 15:7). Others say that it was an etrog tree and that is why it is the custom for women to tear out the tip of the etrog on Hoshanah Rabbah. That is to say, they give money to charity because “charity saves from death” (Proverbs 10:2), and so that God should protect the child she is pregnant with. Since she did not eat from the apple, may the woman give birth to her child as easily as a hen lays an egg, without pain. The woman should say, “Lord of the universe, because Eve ate the apple, we women must suffer the terrible fate to die in childbirth. Had I been present there, I would not have derived any benefit from it, just as now I did not want to make the etrog ritually unfit.” It was used for the fulfillment of a commandment for seven days, but now on Hoshanah Rabbah, the commandment is ended. I am not quick to eat it, and just as I have little benefit from the tip, so did I have little benefit from the apple that you forbade.

Suggested Reading

Overturned Tables

Despite his incontestable Jewishness, Jesus never participated in a Seder as the Mishnah describes it any more than he intended for Judeans to abandon biblical law for the worship of God’s only begotten son.

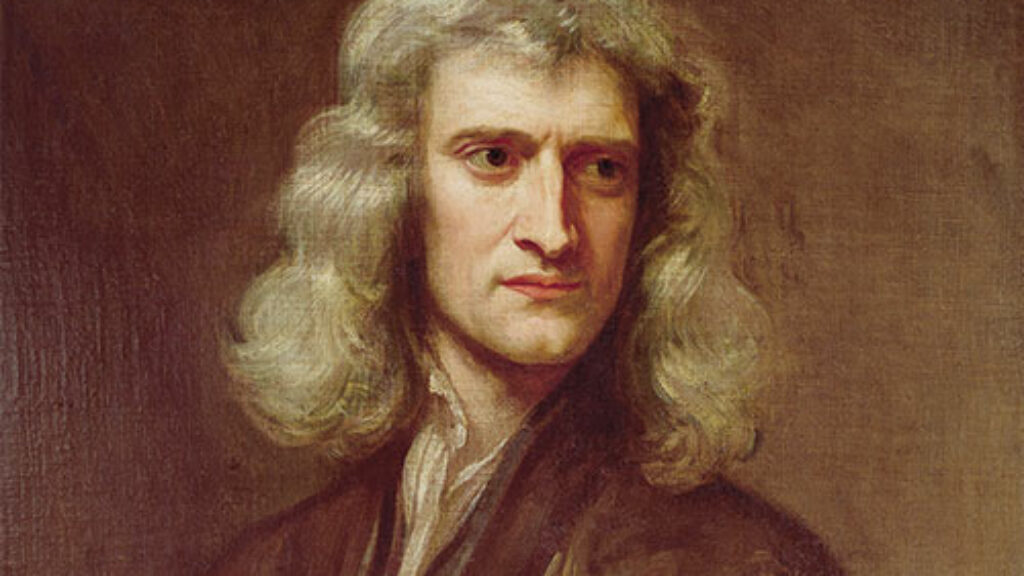

Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions

It takes a bit of a genius to successfully study a genius, and in this case one must first master the millions of words Isaac Newton wrote about natural theology, doctrine, prophecy, and church history.

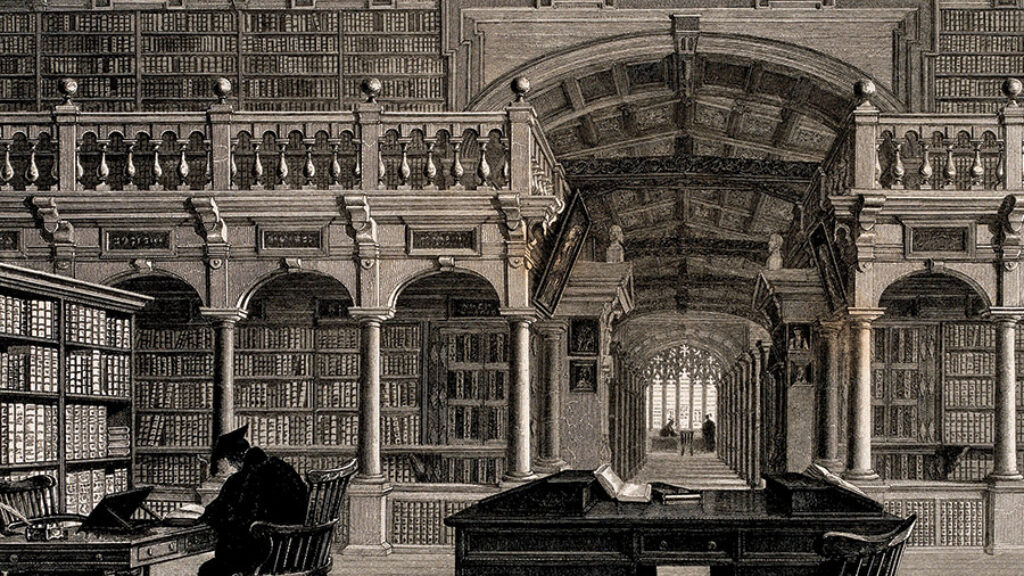

Jerusalem in Albion

The inclusion of Hebrew manuscripts was a priority for Thomas Bodley in 1598, when he began turning the university’s library into the institution of international and historic renown that would bear his name.

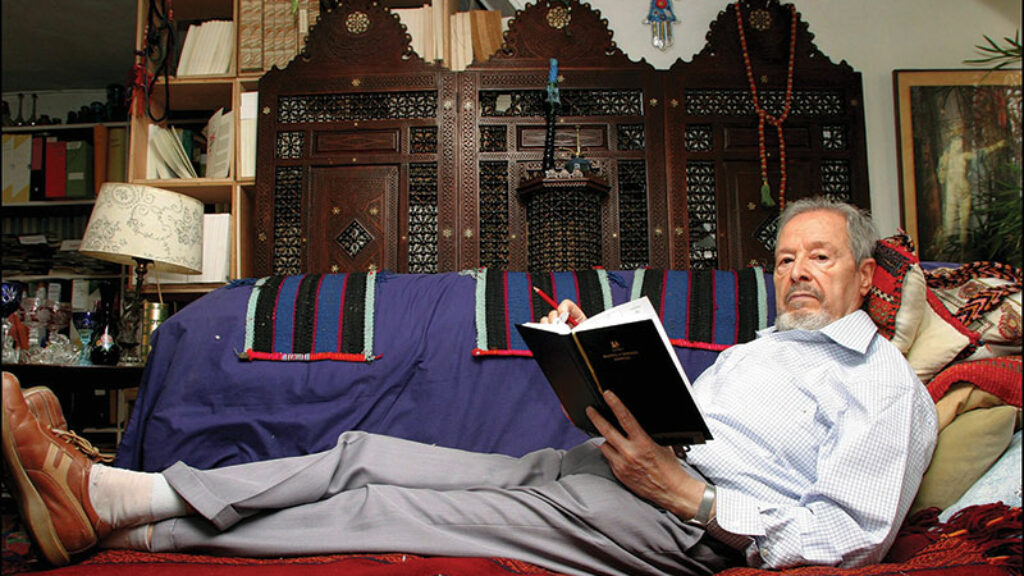

Telling the Whole Truth: Albert Memmi

Albert Memmi began his career as a writer of fiction, but, with the appearance of The Colonizer and the Colonized in 1957, the novelist who wrote like a sociologist became a sociologist who wrote like a novelist.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In