Roth’s Roth-Centricity Was Just Fine

In a New York Times essay, “What Philip Roth Didn’t Know About Women Could Fill a Book,” novelist Dara Horn criticizes Roth’s inability (or refusal?) to create complex female characters. She begins with her own remembered reaction, as a 15-year-old Short Hills, New Jersey, resident, to the novella Goodbye, Columbus:

The town, still leafy and affluent, felt familiar. What didn’t feel familiar was Brenda Patimkin, the Newark narrator’s love interest. Vain and vapid, Brenda, whose striving parents were among the first Jews in exclusive Short Hills, was the sort who had her nose “fixed” to fit in with her Harvard classmates.

Brenda, to Horn, failed as a character, not because Roth’s depiction of Jewish women is dated and at times offensive, but because she didn’t ring true: “The problem is literary: these caricatures reveal a lack of not only empathy, but curiosity.” After praising Shakespeare for at least considering Shylock’s perspective, she adds, “Philip Roth’s works are only curious about Philip Roth.”

Since Roth’s death last week, tributes, along with some misgivings, have flooded the Internet. It did not take the past few days’ output to convince me that for a young Jewish woman, Roth novels might be jarring. I’m 34 but began reading him as a teenager and felt that same mix other critics have described of being represented as an American Jew, yet profoundly ignored as a woman. Except, unlike for Horn, it wasn’t Goodbye, Columbus, with its “princess” cliché, that got to me. Yes, Brenda was uptight and weak-willed, afraid to sweat, and prepared to choose obeying her financially generous parents over having an adult sexual relationship with Neil, a young man not as posh as herself. But to my adolescent self, preoccupied with whether boys would like me, Portnoy’s Complaint was more disturbing. Much of the novel is devoted to Jewish women’s inadequacies, and to (white) non-Jewish women’s charms:

But the shikses, ah, the shikses are something else again. Between the smell of damp sawdust and wet wool in the overheated boathouse, and the sight of their fresh cold blond hair spilling out of their kerchiefs and caps, I am ecstatic.

A Jewish woman as a stuck-up love interest was one (tolerable) thing; the portrayal of us as sexual nonentities, something else.

Once I reached the part of the novel where Alex Portnoy is in Israel and can’t . . . perform in the presence of an Israeli Jewish woman, the point had already been made. Whatever it was, Jewish girls—girls like me—were lacking it. What a change from Goodbye, Columbus, with Neil’s post-break-up wallow, after the two parted ways: “And I knew it would be a long while before I made love to anyone the way I had made love to her. With anyone else, could I summon up such a passion?” In the Portnoy universe, a Brenda—a Jewish woman with (stereotype-meeting) flaws, yes, but an allure all the same—couldn’t exist.

Upon my reflection, though, it wasn’t exactly Portnoy that left me so shaken. It was how the novel’s approach to Jewish womanhood fit so seamlessly into the culture. The notion of Jewish women as revolting, paired with that of non-Jewish women as inherently alluring, appeared (and continues to appear) everywhere: in Woody Allen movies, in sitcoms (Elaine’s “shiksappeal” on Seinfeld and, later, Howard’s grotesque off-screen mother on The Big Bang Theory).

It’s tempting to blame Roth for introducing negative stereotypes of Jewish women into mainstream culture, but the stereotypes themselves were already around. Historian Paula Hyman’s Gender and Assimilation in Modern Jewish History demonstrates that the intersection of anti-Semitism and misogyny long predated Roth. Portnoy, like his creator, was a product of the culture.

Still, I’m not convinced Roth’s Roth-centricity—offensive though it could be to the not-Roth population—constitutes a literary weakness. There’s great (and mediocre) fiction across the autobiography to fantasy spectrum. The ability to persuasively imagine the perspective of those from other cultures (or planets!) is indeed a form of literary talent. But to treat it as inherently superior to the ability to describe one’s own experiences in a way that’s relatable across time and identity is to confuse literary merit with a type of virtuosity, one that deserves praise, but that hardly exhausts what fiction can accomplish.

Rather than lamenting that Roth failed to create more three-dimensional Jewish women characters, why not turn to works by Jewish women authors? Erica Jong’s lust-filled 1973 Fear of Flying is the first that comes to mind. But so, too, does Rebecca Goldstein’s 1983 The Mind-Body Problem. Unlike Portnoy, whose sexual adventures are fueled by the desire to fuse with (or screw with) Gentile America, Goldstein’s protagonist Renee Feuer’s are driven by the (perhaps more gender-specific) desire to get as close as possible to (male) brilliance. These are just two novels I read, long after encountering Roth’s works, that helped me realize what felt missing in his works was absolutely out there, just elsewhere.

Despite the rich literature by American Jewish women, including sexuality-themed midcentury fiction, it remains sadly true that the Rothian Jewish experience is entrenched, in the culture, as the Jewish experience. But I don’t believe the corrective involves wishing, as Horn does, that Roth had been more deferential to the qualities of Jewish New Jersey women, who she notes are “talented professionals in every field, and often in those two thankless professions that Roth quite likely required to thrive: teachers and therapists.” Giving thanks is a great quality in life, but not generally the aim of great fiction.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Family Secrets

“We beam with pleasure. We are in a place where our name is known. For both of us, this is astonishing. An absolute first.”

An Affair as We Don’t Know It

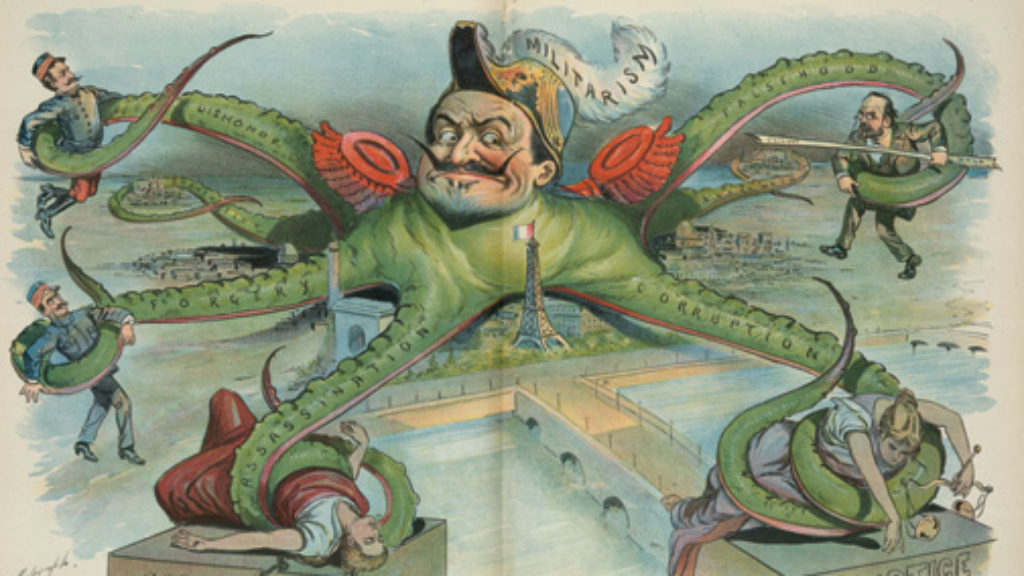

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit.

The Play’s the Thing: A Revolutionary New Haggadah

The exodus from Egyptian bondage was a good thing. What about a haggadah that is "unbound"

A Little Arabic within Our Hebrew

Tracing lines of a linguistic heritage through Hebrew poetry.

amy.caplan

Writers can write about whatever they choose. Obviously. Roth's genius is not in doubt. Nevertheless, eventually I just couldn't tolerate his loathsome caricatures, lack of sympathetic understanding, and reductionist hyper-sexualization of women. I think that's Dara Horn's point. I also detested his graphic descriptions of bodily functions, the worst being the fecal incontinence of his father in Patrimony - how humiliating to be immortalized that way. So I stopped reading Roth because he alienated me. His incandescent writing simply could not outweigh my revulsion - I felt I was being complicit in my own degradation.

firebird1878

When Phoebe Maltz Bovy says "Rather than lamenting that Roth failed to create more three-dimensional Jewish women characters, why not turn to works by Jewish women authors?" she is implying that instead of complaining about Roth's Jewish women characters, Horn and anyone like her should be reading Jewish women authors. However, Horn has not only read such authors, she IS one of them herself. And the subject of her opinion piece is not those authors, but Roth, so why shouldn't she say what she thinks about him? Bovy twists Horn's whole point unfairly. All Horn is saying is that she can live without Roth's novels, thank you; and I second her. Why read an author whose views of people like you are wholly inadequate and for whom those views are absolutely central? Roth was a misogynist, and it affected his novels on a deep level. I applaud Dara Horn's courage in standing up and expressing her true experience and feelings, especially at this moment, when everyone is taking stock of Roth's work. Dara Horn speaks for a lot of us.

Stephen Feingold

While many have complained of Philip Roth’s negative portrayal of Jewish women, those critiques fail to address that Roth is equally harsh in his portrayal of Jewish men. What attracts the male protagonist in Goodbye Columbus to Brenda? Her money After all, he used his cousin’s membership at a posh country club precisely in order to meet a rich Jewish girl. Portnoy’s Complaint ends with the psychiatrist saying now that he has heard the tale they can begin treatment of this deeply disturbed charactrr.

Roth captured the failure of American Jewish life in the years after World War II In response to the Shoa, American Jews were focused on becoming American and operated on the belief that American values were equivalent to Jewish values. But, of course, fidelity to certain Jewish observances such as marrying within the faith were inconsistent with American pluralism. Commitment to Jewish community as a central principal contradicted American values promoting diversity and equality.

Roth portrayed the emptiness that was the result of this warped perspective. In Defender of the Faith the protagonist is a Jewish Sargent who has already served in combat during World War II. He rejects the efforts by Jewish soldiers in basic training to avoid a combat assignment and who repeatedly seek special favors based exclusively on a common heritage. In The Concersion of the Jews we see the reaction of a thoughtful Jewish child in Hebrew School to an explanation about why Jesus could not be the child of a virgin based on a scientific explanation. He wants to know how to reconcile that explanation with the Rabbi’s previous explanation-that God performed miracles on the Bible. The Rabbi is clearly not even able to comprehend the contradiction and becomes so indignant that he has to claim the child is mentally unstable. In Goodbye Columbus Brenda’s mother is fixated on whether Brenda is a Conservative or Reform Jew when it is clear that the only value to her in those designations are the social and not religious implications.

Roth’s fixation on the comparison of Jewish and non-‘Jewish women reflects the ultimate tug of war for Jewish males coming of age in the 50s and 60s. They had been raised to value Americanism and to aggressively pursue the upper middle class dream. Wasn’t the non-Jewish woman with a boat house and a house in an exclusive community the most coveted part of how that dream was conveyed to all American men? If Jewish values were the same as American values, then was it wrong to marry someone who shared those values even if not Jewish? In a culture fixed on status and upward mobility wasn’t marrying a non Jew more likely to achieve that goal? Wasn’t marrying the Jewish woman a step backward?

If Jewish women are repulsive is that because in the 50s and 60s the primary responsibility of the woman was the home. While Brenda’s mother loved her social standing as a Jew living the upper middle class dream, she was not expected to make her way in the world of commerce. As distant as she was from any meaningful Jewish connection, she still focused on such things as whether to be a Reform or Conservative Jew. Wasn’t that sort of preoccupation inconsistent with the message conveyed to Jewish men? The grosstique presentation of Jewish women represents the grosstique contradiction presented Jewish men of that era it is far more an indictment of Jewish life and Jewish leaders than it is a condemnation of Jewish women

Roth’s personnel choices in his life and death suggest in the end he choose Americanism over Jewishness. But his writing is the best most honest exploration of the causes behind the massive growth in intermarriage since Goodbye Columbus was published. The world Roth painted was filled with these contradictions and his characters were enraged by the contractions inherent in American Jewish life. In some ways he is like the child in Conversion of the Jews. He is asking some very sharp and difficult questions and for

Much of his life and continuing into his death, too many Jews are like the Rabbi in the story who insists that such questions and characterizations are nothing more than the ramblings of a deeply deranged man

I suggest those interested in Jewish continuity would be better off exploring the contradictions that continue to plague American Jewish life

Stephen Feingold

Much has been written about Roth's horrific treatment of Jewish women. His treatment is harsh. But that harshness should not deter us from seeking to understand what it derives from. I believe that ultimately his portrayal of Jewish women is part of the message about the grotesque nature of American Jewish life in the 50s and 60s.

First, we should consider that Portnoy's Complaint -- his most insulting and demeaning portrayal of Jewish women -- ends with a psychiatrist telling the protagonist that now having heard the tale they can begin the treatment. The male protagonist in both Portnoy's Complaint and Goodbye Columbus are not icons of good. Neil in Goodbye Columbus meets Brenda when he manages to get his cousin to invite him to her rich country club. He is seeking a way into the world of the Upper Middle Class even as he is stymied in finding a career path.

Roth's stories again and again portray the shallowness of American Jewish life in the 50s and 60s. In the wake of the Shoa, American Jews are seeking to blend into America. The message conveyed is that Jewish values are virtually identical to American values. In seeking the American dream, one is fulfilling one's Jewish destiny. I am reminded of how as a child in the 60s when my best friend and i were asked what we wanted to be when we became adults the response to my friend's desire to become a lawyer was far more positive to my statement that I wanted to become a Rabbi.

This perspective, of course, was filled with contradictions. If Americanism stood for plurality, Judaism still required marrying with the faith. If Americanism was based on hard work, fairness, and merit, Jewish community still required an absolute commitment to Jews above anyone else.

In Defender of the Faith the protagonist is a Jewish sargent who having fought in World War II is now training new recruits during the last years of the war. He is sought out by new Jewish recruits who at first seek special favors to celebrate their Jewish tradition which they then ignore. He ultimately rejects the plea for a noncombat assignment deciding in favor of Americanism and rejecting that wrapped view of Jewish community.

In The Conversion of the Jews we meet a Jewish boy who truly seeks to understand God. He questions the Rabbi's explanation that science refutes the possibility that Jesus was the son of a virgin by recalling the Rabbi's earlier message about God's miracles and ability to do anything. The Rabbi does not even understand the nature of the contradiction and becomes so outraged by the question that he manipulates the situation so that he can call the boy mentally ill.

In Goodbye Columbus Brenda's mother is preoccupied with whether Brenda is a Reform or Conservative Jew though it is obvious that those designations only matter based on their equivalence to social status and not based on even a basic understanding of the religious differences between the two denominations.

Roth's men are constantly struggling with the contradictions between values which they have been taught were in fact identical. Indeed, the focus of their education has been on American ideals with Jewish values an after thought. But if the purist of Americanism would also fulfil Jewish values, why not marry a non-Jew? The ideal women of the time was the non-Jew with a boat house in an exclusive community.

Women of this period were associated with maintaining the home. And the home was the only place where Jewishness played out in this period. Additionally, in this era before women's liberation, Jewish women did not have the same pressures for financial success. Thus, while Brenda's mother relished living the upper middle class dream and was suspicious of a Jewish boy with lesser means, she was still concerned about such unimportant things as whether one was a Reform or Conservative Jew. If Roth's portrayal of Jewish women was grotesque, so was his portrayal of this shallow Jewish lifestyle in general including its Jewish men, who as we see in Portnoy's Complaint require psychiatric care.

Throughout his life and continuing after his death, many explore the important messages conveyed by Roth's harsh and accurate portrayal of Jewish life in the 50s and 60s. He resembles the child in The Conversion of the Jews whose questions so disturb the Rabbi that he must find some way to label the boy deranged rather than explore the emptiness of his own answers.

Roth seems to have in the end choose Americanism over Jewishness based on instructions he left about his funeral. That saddens me. But for those of us interested in Jewish continuity I suggest that we not let the offensive nature of his portrayal detract from the serious indictment he has made of American Jewish life. His work provides the best insight into why intermarriage exploded in the 60s and 70s as the majority of Jews outside the Orthodox camp continue to find the explanations from the liberal forms of Judaism unconvincing.