Family Secrets

The past is present in Eleanor Foa’s charming memoir of her travels through Italy with her younger sister, Pam. Foa’s chronicle of family tourism on a deluxe budget replete with savory meals and vintage wines is nothing less than an armchair treat, especially when the possibility of such travel is so remote. But the picturesque surroundings—medieval castles and Renaissance walls—are also darkly tinged and echo with displacement and loss. The book is a jumble of family and historical research, emotional introspection, and convivial travelogue. Foa makes the juxtapositions work, striking a tone that deftly captures each mood in turn.

Foa was born in Italy on the cusp of World War II, escaping with her parents as a baby before memories of her first homeland could leave an imprint. By the time her younger sister, Pamela, was born, the family was already settled in the United States and their American lives. Decades later, when Foa deplaned in Milan, it had been more than 20 years since she had stepped foot on Italian soil and the first time she had traveled with her sister, a federal prosecutor, as an adult. In the rental car, Eleanor imagines them as “Thelma and Louise on the Autostrada,” but they’re actually doing something very different. Instead of running from their past, the sisters rush toward it, investigating their family history with a trail of clues gleaned from remembered conversations, letters, and family photos and papers.

Eleanor and Pam decided to embark on this sojourn into family history after the death of their mother, Lisa, in 2006. The ostensible goal was to reconnect with family members they hadn’t seen in decades. But for Foa, the greater purpose was to untangle at least some of the contradictory, ambivalent, and (yes) mixed messages of their multiply hyphenated Jewish-Italian-American household. (That Foa’s mother was a German Jew is quickly dismissed: “Our food was Italian. Our parents’ friends were Italian. Our parents spoke Italian to each other, and mother never uttered a single German syllable to us or to anyone.”)

Foa’s list of family puzzles is long. To begin with, although their father, Bruno, often proclaimed that “family is everything,” there were deep, unexplained rifts. They rarely socialized with some of the few nearby relatives who had also fled the Nazis for America. Indeed, her mother’s older sister, Alma—whose husband, she mentions blithely, was Isaac Bashevis Singer—barely rates a cameo. Perhaps this is because Foa’s aunt abandoned her first husband and their two children to marry this “impecunious Yiddish writer from Poland,” but perhaps it is just because Lisa disapproved of Singer’s table manners. Her father’s first cousin Walter came to dinner three or four times a week, but his nieces were never permitted to visit him at his home.

Why did her family “sip water and wine out of Baccarat glasses and eat meals served on gold-rimmed Nymphenburg china” by their maid, even as her mother had to ask for money for every piece of clothing that she needed? Why did her father, who worked hard to go from a war refugee to the owner of a Park Avenue apartment, a condo in Florida, and a seven-figure portfolio constantly tell her money was unimportant and paint the Foa family men as not particularly successful in business?

Foa’s father spoke little of his past beyond his courtship with her mother and their escape from Europe just before World War II. More than that, Foa suggests her parents preferred to steer clear of uncomfortable memories that would contribute further to the pervasive atmosphere of regret, guilt, and remorse that swathed the household. There were enough problems in the present: their mother’s persistent moodiness and their father’s restless travel and philandering.

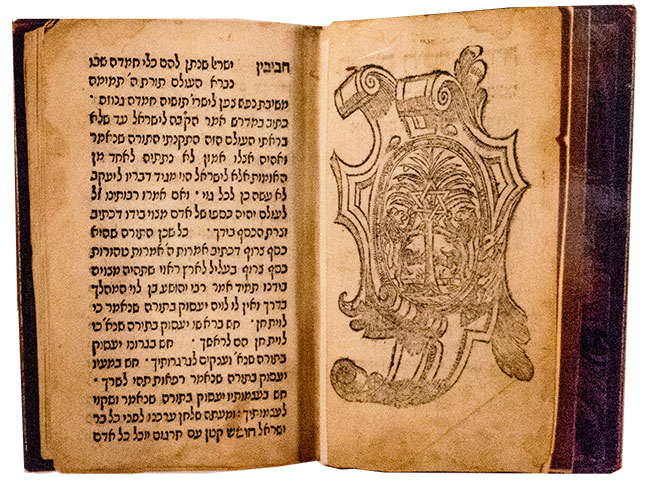

After their mother died in 2006, the sisters packed up their parents’ Saratoga condo. Eleanor perused many boxes of papers, letters, and photos she had shipped to her apartment in New York, though they shed little light on the mysteries of her childhood. In the 40-page typewritten history of the Foa family her father wrote in 1985, the year he turned 80, he briefly mentioned the most famous Foa ancestors. These were the eponymous I Fratelli Foa, printers of Bibles and Hebrew prayer books in the 16th century, a time when it was virtually impossible for Jews to get a license to print. Eleanor and Pam had first heard of them a decade earlier, when an Israeli cousin sent them reprints of their printer’s colophon. They would encounter the emblem again and again during their travels in Italy.

Foa fills in her father’s 40-page outline by interspersing accounts of her travels with her own recollections, family letters from the 1800s and 1900s (including many her father wrote to her, beginning when she was just five), plaques in old synagogues, and research shared by local historians rung up by friendly hoteliers. And every stop on the itinerary (Mantua, Cremona, Parma, Turin, Rome, Naples)—where the sisters dive into memory-laden, gossip-filled reunions with generations of the extended family who still make their homes in the Italian towns and cities where their ancestors once lived—reveals more of the family’s story as well as that of Italian Jewish history.

Jews first arrived on the Italian peninsula more than two thousand years ago. The Foa family itself probably did not set foot in Italy until the Spanish and Portuguese expulsions of the Jews forced them out of their homes on the Iberian Peninsula. Their first stops in the regions that today make up Italy—like those of the two sisters on this trip—were in northern Italy.

In the medieval town of Soragna, the sisters uncover the first local memories of their family lineage. At the Parmigiano Reggiano Museum, the wife of the farming couple that owns the museum comments that “Foa is a distinguished name in Soragna.” Elated, Foa writes this:

We beam with pleasure. We are in a place where our name is known. For both of us, this is astonishing. An absolute first. . . . We take photos. We exchange cards. She hopes we tell more Americans about the museum. As we make our way down the long cobblestone path in the rain, I suddenly wonder how this couple, their parents, and others in the village behaved during the round-up of Jews that took place after 1943. It’s the kind of deeply suspicious question Mom might have voiced. Dad, never.

Few traces of Soragna’s Jewish community remain; the one building that still stands had served as the town’s synagogue since at least 1584. By 1855, the Jewish community was large enough to finance an exuberant neoclassical-style renovation of the building, with Corinthian columns and a barrel-vaulted ceiling. In 1939, it was confiscated by the Fascist government. After the war, with a dwindling Jewish community—the last member died in 1971—it was abandoned altogether. Forty years after Mussolini had taken it, a patron brought new life to the synagogue building as a regional museum of Jewish life and history.

Foa also finds her family’s name in archival records. In a notation dating to 1547, Giuseppe Foa is described as the owner of a local lending bank. Foa is perplexed; her father had always claimed he (and his daughters) had inherited a genetic incompetence with anything to do with money (notwithstanding his success as an economist who flew first class and stayed in four-star hotels at his clients’ expense). In his typewritten history, Bruno began the family story in 1551, just four years after the notation about his moneylending ancestor, who he never mentioned. Had her father not known about Giuseppe? Or was he ashamed of the stereotype of the Jew as usurer? Had her father perhaps used this narrative of financial incompetence as a way to distance himself from antisemitic stereotypes about Jews and money, Foa wonders, writing the following:

The more I turn over in my mind the possibility that some of our ancestors were, in fact, moneylenders, the more sense it makes. Because if moneylenders were the only exception to the “No Jews” rule in the Parma region, how else did the Foas thrive in these tiny villages . . . when most of their Jewish brethren were already restricted to the ghettos of Venice, Turn and Rome? Why I wonder—and still wonder—did no one in the family ever entertain that possibility?

Their journey also fills in facts beyond Bruno’s cursory mention of I Fratelli Foa publishing house. The press, which published more than 30 works in Hebrew between 1551 and 1590, remains well known to bibliophiles, who prize the few copies still extant. Foa sees the publishing firm’s distinctive colophon—which, in addition to the family name in Hebrew, depicts two lions of Judah on either side of a palm tree and a Star of David—again and again, once even painted on the ceiling of a Sabbioneta home that had perhaps housed members of the family.

Other public mentions of Foa relatives carry grim reminders of the Holocaust. At the Jewish museum in Soragna, for instance, the sisters are startled to discover a familiar name on a memorial plaque honoring Jews murdered in the Holocaust. It is Aldo Foa, husband of their father’s favorite sister, Paola. Aldo had been an anti-Nazi partisan who, after his capture, was murdered in Mauthausen. Foa writes this:

Standing before this plaque, I am gripped by a terrible and profound sense of loss. And by the miracle of my family’s survival. . . . For the first time, I feel as though I belong not only to the Foa family but to the extended Italian Jewish family of roughly 40,000 souls who, before World War II, knew each other, intermarried and gossiped about each other as if they’d grown up in the same town.

Those emotions intensify in Naples, the town where Bruno was born and which, Foa notes, “but for historic happenstance, could have been my home town.” The warmth is palpable during the series of one nonstop family get-together after another, where the sisters are treated to regional cheeses, fried eggplant served with zesty spices, flavorful tomatoes just plucked from the garden, crispy baked zucchini, and delectable pastries. But then talk switches to the devastating years of Mussolini’s anti-Jewish racial laws, the terror of the Holocaust, and the postwar struggle to build life anew in a now bombed-out, impoverished country. Against this backdrop of family anguish, the sisters begin to understand, as they never could before, the grief and guilt their father had carried with him to America.

Bruno had been so devoted to his widowed mother, Eleanora, that he had described their relationship as having been like a marriage. But in 1939, having managed to escape Italy and settle in London with his mother; wife, Lisa; and baby daughter, Eleanor, he was impossibly torn by his domestic situation. The two women, displaced and traumatized, clashed fiercely. Bruno arranged for his mother to return to Italy to stay with family members there. Shortly afterward, the war began. With all communication from then on impossible, Bruno did not know whether he had sent his mother to her death.

Despite great hardship, his mother did survive, and immediately after the war, Bruno rushed to visit. But his decision haunted him, leaving him anxious and agitated on every visit “home.” “My father never let go of the family fantasy, never admitted the truth to himself, which was that he loved living 5,000 miles away from Italy.” Foa and her sister traveled the same five thousand miles to resolve this paradox.

Suggested Reading

The Great Gaon of Italian Art

Berenson’s teacher Charles Eliot Norton dismissively dubbed Berenson's method the “ear and toenail school,” but Berenson employed the technique in his first book to great effect.

In Giorgio Bassani’s Memory Garden

If you visit Ferrara, Italy, you can let Giorgio Bassani be your melancholy guide as you stroll along “the crowded rows of stores, shops and little outlets facing each other” to arrive at the synagogue’s “baked-red facade.”

Not So Innocent Abroad

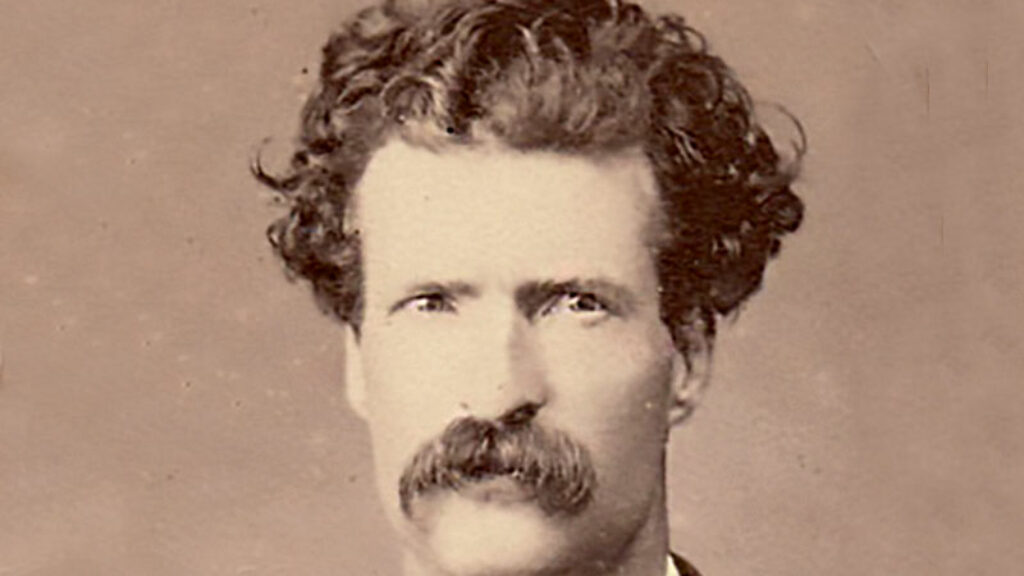

Mark Twain's book about his travels to the Holy Land and back is his bestselling book over the course of his lifetime and remains one of the bestselling travel books of all time.

Passport Sepharad

The recent offers of citizenship by Spain and Portugal tap into a long, rich, and complicated Sephardi history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In