Vive la Differénce! A Rejoinder to Joshua Holo

In his response to my essay, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion’s Dean Joshua Holo had the difficult task of distancing his institution and the Reform movement from Michael Chabon’s now-infamous commencement address calling for the dissolution of all Jewish particularism while at the same time justifying the choice of Chabon as commencement speaker. It is not a task I envy him, and I can say that he has responded with erudition and grace. Nevertheless, I would like to push back a bit against his response, both to clarify my aims in critiquing Chabon’s speech and even more so to continue an important conversation that, as Holo notes, has been going on for two centuries.

Holo (charitably, as he is aware) brackets Chabon with the great 19th-century Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider as an uncompromising universalist and contrasts them with Steinschneider’s contemporary Abraham Geiger and his heirs in the Reform movement, who retain a sense of (particularist) commitment to the Jewish community while remaining on the liberal side of the spectrum. The Conservative movement and Modern Orthodoxy, which are both also products of the 19th-century Jewish Enlightenment are, on this view, simply further along the same spectrum that runs from extreme particularism to extreme universalism.

I am sure that Holo oversimplifies—as I must—due to the constraints of space and genre, yet I must take issue with the presentation of particularism and universalism as polar opposites. On one hand, the two are not necessarily contradictory. The Jewish sense of mission—of being a light unto the nations and a kingdom of priests—is of universal scope but demands that those charged with the mission remain distinct. It is precisely our particularism that enables our universalism. This theme can be detected in a great deal of modern Jewish writing, especially that of Lord Jonathan Sacks.

On the other hand, purging Judaism of its particularity usually results not in greater universalism, but simply a different particularism. The German Jewish Enlightenment project did not really liberate Judaism from exclusiveness and particularism so much as it exchanged them for bourgeois cosmopolitan Deutschtum, which it mistook for universalism. The polar opposite of Jewish particularism is sometimes not universalism but non-Jewish particularism. Already in the early 19th century, particularly in the Habsburg realms, rabbis such as Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Rimanov in Galicia and Rabbi Moshe Sofer in western Hungary and their intellectual heirs saw this clearly. They insisted that Jews could live within a modern state, as citizens, without having to become “good” Germans, Russians, or Hungarians. They demanded the acceptance of Jews qua Jews, in all their beautiful, idiosyncratic otherness.

This brings us back to Michael Chabon’s speech. Dean Holo and I agree that Chabon’s call to “knock down the walls”—seemingly all walls—separating Jews from others is factually misguided and philosophically nihilistic. However, Holo agrees with Allison Kaplan Sommer that, nonetheless, Chabon’s speech “works as anger” and even tries to grant it some intellectual heft by treating it as a restatement of the view Gershom Scholem attributed to Moritz Steinschneider that Judaism ought to be given a proper burial. It is doubtful that this is a fair characterization of Steinschneider, but, even if it is, Steinschneider spent a lifetime of brilliant, meticulous scholarship on that task. Chabon doesn’t even understand his own examples and can’t be bothered to google them.

Chabon’s speech doesn’t work, not even as anger, kal va-chomer as a restatement of Steinschneider. For, whatever angered Chabon, his target was Judaism in all its particularism. His alternative masquerades as a kind of universal hybridity—everything “cooked up in the same skillet”—but is really just omnivorousness. Chabon wants us to sample it all but refrain from ordering too much of any one item on the menu. Nothing should be foreign to us, but nowhere should be home, either. Unlike the late gourmand Anthony Bourdain, Chabon shows no desire to encounter other cultures in their deep idiosyncrasy.

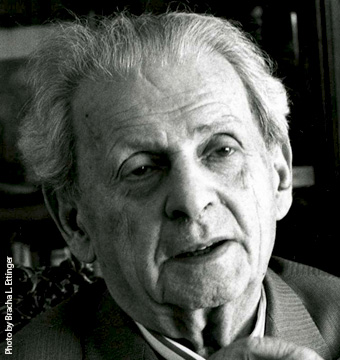

Perhaps the most telling example of this simplistic attitude in Chabon’s speech was when he suggested that barriers invariably mark those on the outside as “Others” and therefore, according to “the logic of the deepest, oldest human evil—less truly human.” The great Litvish-French-Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, who introduced the “Other” into our moral vocabulary, taught precisely the opposite. It is only when one encounters the other qua other that one truly dignifies them as fully human. If everyone is, in some sense, the “same,” if my recognizing the humanity of the other is contingent upon my seeing my own reflection in them, then it is not universalism but narcissism.

The alternative to Chabon’s world of no Others—a world of cosmopolitan sameness—is a world in which we are all each other’s others. Accepting the other qua other begins—must begin—with the acceptance of our own otherness in all its particularity.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Our Kind of Traitor

More than 40 years after the Yom Kippur War, some of its battles rage on, including the debate over the spy Ashraf Marwan’s true loyalty.

The First Debate Over Religious Martyrdom

The name of God is sanctified when life is preserved, not when it is proclaimed great an instant before life is obliterated.

Wild Things: The New Neo-Hasidism and Modern Orthodoxy

Who are Joey Rosenfeld and his pseudo-Hasidic pranksters, and what does their success have to do with the future of Modern Orthodoxy?

A View from Reservoir Hill

A shul that never left the Old Jewish Neighborhood lives, volunteers, and prays through the recent crisis in Baltimore.

Paul Jeser

Dean Halo continues to use very wordy responses to defend what is not defendable.

Bottom line - He and his colleagues invited an anti-Israel self-hating Jew to spew his trash at a graduation ceremony. The fact that they don't have the derech eretz to apologize reinforces the harm they have done to HUC and the Reform movement. Shame on them!