Wild Things: The New Neo-Hasidism and Modern Orthodoxy

A couple of years ago, a prominent Modern Orthodox synagogue in Teaneck, New Jersey, invited the community to study with a young man named Joey Rosenfeld from Saint Louis, Missouri. As the synagogue filled up with a youthful crowd unfamiliar to many congregants, the atmosphere began to shift from suburban Orthodox bourgeois to a more fervent and decidedly less decorous hipster-Hasid aesthetic, exciting some and discomfiting others.

Teaneck is a leafy township of some forty thousand souls, including about fifteen thousand Modern Orthodox Jews, just across the Hudson from Yeshiva University, Modern Orthodoxy’s flagship institution. Many people who pray in Teaneck’s synagogues and frequent its kosher restaurants were educated at the university, which prepares young women and men to lead lives as observant Jewish professionals. Although they comprise just a small percentage of American Jewry, by dint of their prosperity, influence, and aspiration to succeed as traditional Jews in contemporary society, Modern Orthodox communities like the one in Teaneck hold special significance in the great arc of the modern Jewish story. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a thriving American Jewish future in which Modern Orthodoxy does not play a key role, and yet the movement is no longer as spiritually confident as it once seemed.

Modern Orthodoxy is what anthropologists would call a “discursive tradition,” one defined by its intellectual commitments. Its synagogues regularly host scholar-in-residence weekends featuring educators, often Yeshiva University faculty and alumni, who come armed with handouts crammed with resonant passages from Tanakh, rabbinic literature, and medieval and modern Jewish philosophy—especially the writings of Moses Maimonides and the Modern Orthodox Maimonidean, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik—often juxtaposed with, or framed by, works of secular literature or philosophy. Rosenfeld is a member of the subtribe, and he prepared nicely curated source sheets to accompany his talks, but when he began quoting medieval and Hasidic mystical writings that are not part of the Modern Orthodox canon, the excitement among some attendees, and the disorientation among others, was palpable.

Rosenfeld wears an old-school black yarmulke and has dark hair, a big beard, prominent eyebrows, and a kind demeanor. He prefers to teach seated, yet when he teaches, he moves—shuckling in his chair, stroking his beard, gesturing with his hands, and excitedly closing and opening his eyes. His teaching that Friday night took place in the synagogue’s social hall, which was set up in Hasidic style, with long tables around which crowded about a hundred people. Rosenfeld spoke extemporaneously, pausing here and there for the spirited singing of largely wordless niggunim.

His subject, the Sabbath, couldn’t have been more familiar, but he approached it from an unexpected angle, speaking of it as the “death of the week.” Rosenfeld invoked well-known rabbinic sources, which he read in conversation with the striking formulations of the Zohar, Hasidic teachings, and Nachman of Bratslav’s tales. He also made reference to Western literature—but it wasn’t Shakespeare or Kant, but Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. The final talk of the weekend was a postmodern mashup titled “The Redemption of Doubt” that riled a few in the audience, especially those still loyal to Yeshiva University’s litvishe (Lithuanian) rationalism. What, some unsympathetic congregants wondered, was this wild rumpus all about? Who are Joey Rosenfeld and his pseudo-Hasidic pranksters, and where did they come from?

The question of origins is the easier one to answer: nearly everyone in attendance was educated in Modern Orthodox institutions but somewhere along the way made subtle, yet significant, changes in weltanschauung and wardrobe. It has been more than a quarter century since Soloveitchik, Modern Orthodoxy’s leading light, died, and no figure approaching his stature has emerged to guide the community through the innovations and upheavals of the twenty-first century. In the intervening decades, Modern Orthodoxy has seen growing numbers of disaffected youth embark on personal journeys both away from and toward greater Jewish piety, sometimes after tasting the intensities of haredi life during a gap year study in Israel. Those who become more religious (“flipping out,” as the saying goes) typically throw themselves into Torah study, often at the expense of the college education and professional career that their parents, their schools, and their Yeshiva University–trained rabbis all expected of them. But Rosenfeld’s acolytes in the Teaneck synagogue didn’t quite seem to fit either model. Neither day school rebels nor black-hatted true believers, they share traits with both. One could discern a new and peculiar religious identity coalescing, one that shared some elements with haredization but also, paradoxically, included an abandonment of dogmatic certainty and religious convention.

Many in the audience knew Rosenfeld from the Internet, where he holds Hasidic court on Twitter, sending out tweets that miraculously distill Jewish mystical thought into 280 characters, like this meditation from September 12:

Yom Kippur is:

R. Tzadok: a mikvah

Vilna Gaon: the other half of purim

Chabad: pleasure of non-pleasure

R. Nachman: eating words

R. Kook: freedom

Izhbitz: a return to Nothing

R. Hutner: the only real day

Kozhnitz: the inner most point

Chazal: happening whether you’re aware or not

Though it presupposes more than a passing knowledge of Hasidism and rabbinic thought, it’s a characteristically virtuosic tweet.

Twitter dexterity notwithstanding, Rosenfeld’s main online contributions are his weekly classes, which he records in his basement and posts on YouTube and as a podcast called Inward with Rabbi Joey Rosenfeld. He’s recorded 150 episodes since January 2019. They are grouped in fifteen thematic “seasons,” each lasting anywhere from just a few episodes to over a dozen and ranging from explorations of “the inner world of addiction” (Rosenfeld is an addiction counselor) to introductions of major Jewish mystical ideas and figures to deep dives into difficult and esoteric works, including a dense book of alphabet mysticism by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook that was once considered unreadable.

In his podcasts, Rosenfeld returns again and again to themes of divine concealment and paradox, faith and doubt, anxiety and depression, joy, desire, and self-realization. Remarkably, this somewhat Kierkegaardian list is not a course of angst-ridden hurdles to be overcome, or at least contained, by the behavioral certainties of Jewish law. Rather, it reflects a divine reality in which these supposed negatives are accorded a position within God. There are also recurring thinkers on Inward who ground and organize the discussion, including well-known historical figures such as Isaac Luria, the Ba’al Shem Tov, and Nachman of Bratslav, as well as more recent and less widely known mystics, such as the Lithuanian kabbalist Rabbi Shlomo Elyashiv (the grandfather of the recently deceased Israeli haredi leader Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Elyashiv) and the contemporary Hasidic master Rabbi Itche Meir Morgenstern of Jerusalem, a Gerer turned Bratslaver Hasid who has a growing and surprisingly diverse following that extends far beyond the Gerer and Bratslaver circles.

On Inward, messenger, message, and medium often converge. In a class on Rav Nachman’s stories, which Rosenfeld describes as “tales that are so ancient that it is almost as if they are rooted in the future and tales that are so futuristic that it is as if they are rooted in the past,” he excogitates on Nachman’s deliberately unfinished tales:

[Rabbi Nachman] doesn’t tell us how the lost princess was saved. He doesn’t tell us about the seventh legless beggar. . . . The lack of the ending in Rabbenu’s tales is the very ending that we are trying to understand—that we don’t need the ends to arrive in order for us to taste the ending. We can taste the ending even prior to the end arriving—that laughter at the end of the joke of the dialectical sway between concealment and revelation that is existence, even though the joke is not finished yet, and the storyteller has not finished the story, the tale is not told over yet. Nevertheless we have the ability to laugh at the joke prior to the punch line.

In his explications of Jewish mysticism, Rosenfeld often turns to the ideas and tropes of continental philosophy. A recent meditation from a series called “The Inner World of Recovering” sounds like something a Hasidic Heidegger might say:

All of us come from someplace, from someplace that has already happened. . . . There always is a silent aleph that rests just beyond the cusp of our consciousness that we can’t quite reach back towards. . . . In spite of all of our best efforts to return back to the origin, back to the aleph, back to that place of silence we can only come close enough to it to realize that we can’t quite reach it. The Holy Zohar, [regarding] when it says [in Genesis 1:2] that “the earth was unformed and void”—“was” implies a past sense that the world was already in a state of desolation, and [the Zohar] has a beautiful poetically evocative language—“mikadmat dena”—where it refers to the chaos of the world, the chaos of the self, of the individual who finds himself stuck, always after something has taken place. Something happened and we find ourselves after the storm. . . . We are tossed into a battle where the bullets are already whizzing by our heads.

While this unexpectedly heimishe fusion of Jewish mysticism and European existentialism is distinctive, Rosenfeld is not the only contemporary Orthodox Jewish thinker now turning to Hasidism for guidance. What is more, this is not the first time we find Hasidism helping Jews cross modernity’s very narrow bridge. There is a history here, one summed up in the term “Neo-Hasidism.”

In the popular imagination, Hasidim are Jewish Rip Van Winkles. Better, they are Herschel Greenbaums, the hero of Seth Rogen’s 2020 dramedy, An American Pickle, who resurfaces in contemporary New York after having been brined in a pickle vat for a century. In fact, alongside its manifest traditionalism, Hasidism has been animated by newness since its founding more than two hundred years ago, which is why it provoked such opposition from the rabbinic establishment in Eastern Europe, who collectively came to be known as misnagdim (opponents).

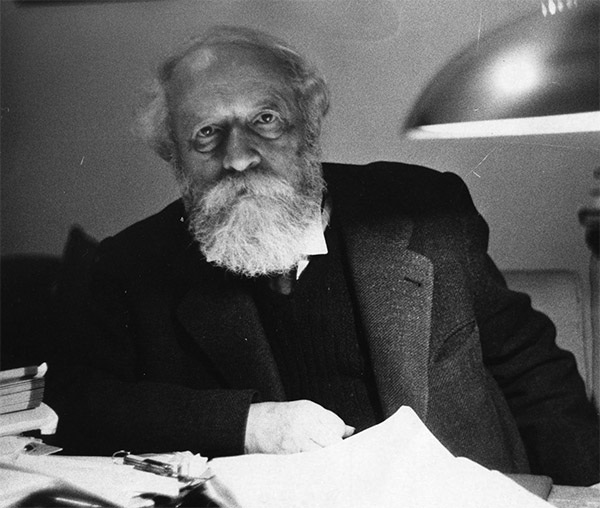

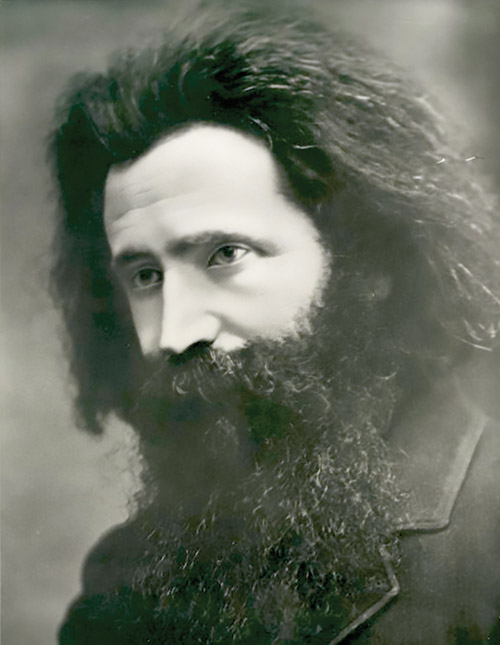

The Hasidic dance of the old and the new is particularly present just beyond the movement’s conventional confines—that is, in the Neo-Hasidism of figures like Rosenfeld and others considerably to the left of him on the Jewish spectrum. The most wide-ranging discussion of Neo-Hasidism’s past and future can be found in Arthur Green and Ariel Evan Mayse’s two-volume anthology, A New Hasidism. The volumes introduce us to the movement’s founding fathers and survey the writings of some of its budding patriarchs and matriarchs. In the first volume, subtitled Roots, we meet the Neo-Hasidic triumvirate of Martin Buber, Abraham Joshua Heschel, and Hillel Zeitlin, along with more recent figures such as Shlomo Carlebach, Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, and the book’s elder editor, Arthur Green.

It was Buber who first laid the groundwork with his bestselling translations and adaptations of Hasidic tales and teachings. In Buber’s reading, the essence of this oral tradition was about reenchanting a disenchanted world, as in this story he retold about Simcha Bunam of Pzhysha (1765–1827).

One evening when Rabbi Bunam was in Danzig he went to the public gardens. They were lit with many lights, and young men and girls were strolling about in bright-colored dress. “These lights are the candles of the Day of Atonement,” he said to himself. “And these garments are the shrouds of those who pray.”

The great historian of mysticism Gershom Scholem gleefully disparaged Buber’s Hasidic revivalism as “drenched in the romanticism and flowery metaphors of the Vienna School.” In a remarkably candid reply published shortly before his death, Buber admitted that his work derived “from the desire to convey to our own time the force of a former life of faith and to help our age renew its ruptured bond with the Absolute”—and refused to apologize for it.

Although there was a time when nearly every literate American Jewish household had a copy of the Schocken paperback of Buber’s Tales of the Hasidim, his younger contemporary Abraham Joshua Heschel is now the more familiar figure. Heschel, who was heir to the Hasidic dynasty of Apt, is perhaps best known for marching from Selma to Montgomery alongside Martin Luther King Jr., proudly decked out in a Hawaiian lei. Yet, in a piece he composed in ornate Late Rabbinic Hebrew and titled Pikuach Neshama (To Save a Soul), selected by Green and Mayse, we meet a far less beatific religious figure:

Our historical experience has taught us that our existence as Jews is not in the category of things which neither help nor hurt. The opposite is true: to be a Jew is either superfluous or essential. Anyone who adds Judaism to humanity is either diminishing or improving it. Being a Jew is either tyranny or holiness. . . . One who thinks that one can live as a Jew in a lackadaisical manner has never tasted Judaism.

There are moments in this burning document when the famously liberal Heschel comes shockingly close to parochialism: “The millions of Jews who were destroyed bear witness to the fact that as long as people do not accept the commandment ‘Remember the Sabbath to keep it holy,’ the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ will likewise fail to be operative in life.” Green and Mayse try to damage-control this fundamentalist declaration in a footnote, yet the text stands as an important testament to Heschel’s radicalism and the radical impulse at the root of Neo-Hasidism.

Like Heschel, Hillel Zeitlin was born into a Hasidic family, in his case, Chabad, and he, too, left its narrow confines to explore the Western philosophical tradition, eventually publishing Hebrew monographs on Spinoza and Nietzsche before reengaging with the Hasidism of his youth in the years leading up to the Second World War. Zeitlin was an impassioned pamphleteer and writer of manifestos. It is no accident that A New Hasidism, which also hopes to launch a Neo-Hasidic revolution, opens with a fervent quotation from Zeitlin about a new spiritual community called Yavneh that he wanted to establish:

Yavneh wants to be for Jewry what Hasidism was a hundred and fifty years ago. This was Hasidism in its origin, that of the BeSHT [Ba’al Shem Tov]. . . . [Yavneh] wants to bring into contemporary Jewish life the freshness, vitality, and joyful attachment to God, in accord with the style, concepts, mood, and meaning of the modern Jew, just as the BeSHT did—in his time.

As his aspirations for, and anxieties about, the Jewish future grew, Zeitlin became a serial organizer of such elitist utopian societies. The surviving documents are a miscellanea of curious texts. They include a self-interview that explains the goals of Yavneh and a charter with a strenuous list of rules for society members. We see in his writing an extraordinary mix of Nietzschean socialism and Hasidic piety as Zeitlin implores his imagined audience to “support yourself only from your own work! . . . Keep away from luxuries! . . . Do not exploit anyone! . . . Sanctify your sex life altogether! . . . Sanctify your Shabbat!” and more. A note accompanying the rules somewhat poignantly announces: “Any reader who has firmly decided to start living in accord with the fourteen principles outlined above, even if not all at once but gradually, may turn in this regard either orally or in writing to Hillel Zeitlin, Szliska 60, Warsaw.” It does not seem as if many Neo-Hasidic comrades showed up at Zeitlin’s door before he was murdered by the Nazis, wearing, Green and Mayse tell us, “tallit and tefillin and carrying a copy of the Zohar in his hand.”

Zeitlin’s key insight, that Neo-Hasidism could only thrive in the form of tight-knit spiritual societies not unlike those among which Hasidism originated, was adopted two decades later by Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, another Jewish thinker with origins in Chabad. Schachter-Shalomi is a fascinating figure who, while serving as a campus rabbi, got caught up in the psychedelic frenzy of his age and yet, judging from the intelligence of his writing—although it is frequently marred by New Age jargon—kept his wits about him.

In an early, orienting essay, Schachter-Shalomi weighs in on his predecessors: about Buber, he observes that his famous ideal of dialogue is wordless, a relation between beings rather than a substantive exchange: “Perhaps Buber is afraid that the ‘word’ would become ‘flesh,’ leaving only a non-dialogical Halakhah,” he writes. Heschel, on the other hand, is thankfully “not afraid that the word will become flesh. He wants it to become incarnate, not in space, but in time.” The problem, of course, is that when you dismiss the form-giving coordinates of space, you are left with an idea, not a community. The Sabbath may be, as Heschel famously wrote, “a cathedral in time,” but humans live in places. As a man of his time, Schachter-Shalomi believed that the solution was to turn not to a traditional rebbe but a guru—a role he ended up filling himself. Indeed, of all the figures anthologized in A New Hasidism, Schachter-Shalomi was the only one who successfully built something like a Hasidic court, one whose influence extended far and wide and included Jews, non-Jews, JewBus, and other wondrously strange birds.

Because of the dual role that Schachter-Shalomi and A New Hasidism’s coeditor Arthur Green played in establishing and advancing twentieth-century Neo-Hasidism, both men appear at the end of the first Roots volume and at the beginning of the second volume, which is subtitled Branches. In word and deed, Green has functioned as the great bridge between the old-new-Hasidism of the past century (he studied with Heschel) and the Neo-Hasidism of the present era. Alongside a distinguished career as an academic and theologian, Green has been a bricks-and-mortar institution builder, founding Havurat Shalom, the first non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic minyan, in Somerville, Massachusetts, in 1968 and, decades later, the nondenominational rabbinical school at Boston’s Hebrew College.

The two-volume structure of A New Hasidism also allows the editors to confront the Shlomo Carlebach conundrum by splitting the mixed legacy of the folk-singing rabbi in two. Carlebach’s ministry was, like that of his old Chabad comrade, Schachter-Shalomi, wildly successful among the flower children—his reach extended from San Francisco, where he founded “The House of Love and Prayer,” to Israel, where he helped establish the hippy town of Moshav Modi’in—and it also resonated among suburban Jews. Carlebach’s uncomplicated tunes, essentially American folk music played on old Jewish scales, became so popular that they are now standards of Jewish liturgy. At the same time, the matter of Carlebach’s sins—allegations of sexual abuse became public mainly after his death and have intensified with the #MeToo movement—could not go unremarked. The editors’ compromise, which I doubt will satisfy anyone, is to include a perceptive critical essay by Shaul Magid and one of Carlebach’s improvisatory teachings. In volume two, Magid depicts Carlebach as a spiritual troubadour who “carried with him the burdens of his own human failings, never apologizing for them—also never denying them—but never overcoming them either.” In the first volume, we get a talk by Carlebach based on the midrashic idea that fetuses learn the entire Jewish tradition while in utero, the “Torah of the Nine Months.” Faithfully transcribed from one of Carlebach’s extended, jazzlike discourses (when Schachter-Shalomi riffs on one of Carlebach’s themes, the latter enthuses, “Yeah, keep on going, brother”), this brilliant homily showcases Carlebach’s charismatic erudition and reminds us of the potential and peril of the charisma at the heart of Neo-Hasidism—and its unhyphenated ancestor, too.

Magid’s essay is not the only attempt in Branches to address problems in Roots. One glaring matter is the exclusion of women, and so volume two treats us to a personal essay by Rabbi Nancy Flam, a Neo-Hasidic leader who helped found the Institute for Jewish Spirituality, called “Training the Heart and Mind Toward Expansive Awareness” about her spiritual journey. There are just a few more women’s voices included in A New Hasidism and also a striking omission—the Israeli Neo-Hasidic poet (and first cousin of the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe) Zelda Schneurson Mishkovsky—so that the well-intentioned attempt at gender parity comes off as tokenistic.

The concluding essays of A New Hasidism attempt, ultimately insufficiently, to correct the American-centric, non-Orthodox orientation of most of the contributions. Briefly, we learn of developments in the Holy Land, where Orthodox Neo-Hasidism melds a disparate set of traditions—sometimes abbreviated with the playful acronym HaBaKuK: Chabad, Bratslav, Kook, and Carlebach—and now thrives in Israeli cities, towns, and hilltops, in yeshivot and midrashot, in popular religious music, and at lively Neo-Hasidic farbrengens.

In a chatty “Closing Conversation with the Editors,” we also get to hear of the octogenarian Green’s liberating discovery of Hasidism “after a bad youthful romance with Orthodoxy” and about the spiritual path of the nearly half-a-century younger Ariel Evan Mayse, who “like a double helix . . . came to Orthodoxy after a bad romance with liberal Judaism.”

Mayse’s reflections on his journey are revealing, but they are by nature personal in perspective and limited in scope. Fortunately, a forthcoming collection by Yeshiva University Press explores, albeit cautiously, the new frontier of Modern Orthodox Neo-Hasidism. Contemporary Uses and Forms of Hasidut is not an anthology of original Neo-Hasidic writings but an anxious account of this new, “potentially destabilizing force emerging from the ‘outer rim’ of the community.” The volume is part of the Orthodox Forum conference series, which was founded in 1989 by Yeshiva University president Norman Lamm to discuss leading issues in Modern Orthodoxy. An old-school proceedings volume, Contemporary Uses preserves a complete list of invited attendees, which reads like a who’s who of the Modern Orthodox chattering class. One way of thinking about the forum is as an informal ecclesiastical council, where religious intellectuals meet regularly to discuss hot-button issues and redraw boundaries. The conference has seen its share of controversy over the years, including a famous gathering in 1998 when theologian Tamar Ross’s paper “Modern Orthodoxy and the Challenge of Feminism” was deemed beyond the pale.

In that light, it is difficult at first to appreciate the urgency of this Orthodox Forum on Neo-Hasidism. What is not to like in the arrival of a little Hasidic spirit—inspiring singing, uplifting teachings, spiritual fervor—in the classrooms and study halls of Yeshiva University? Echoing the tension in Teaneck over Joey Rosenfeld’s visit, some of the essays explain how Modern Orthodox Jewry strongly identifies with Orthodoxy’s rationalist strain, which originated in the anti-Hasidic cantons of White Russia and took distinctive shape in the square suburbs of the northeastern United States. Some of the older conference participants recall their surprise upon learning that a growing number of students at their alma mater were studying exotic Hasidic texts rather than Talmud, participating in ecstatic Hasidic gatherings, and adopting Hasidic practices like growing payos or slipping shabby-chic gartels around their waists before prayer. There is also bewilderment concerning the appointment of Moshe Weinberger, a rabbi with a major Neo-Hasidic congregation on Long Island, New York, to the position of spiritual director (mashpia) at Yeshiva University and the hiring of the similarly named but unrelated Moshe Tzvi Weinberg as a mashgiach ruchani, a kind of spiritual counselor, at the institution.

Even for those without a personal stake in the future of Modern Orthodoxy, the story of Neo-Hasidism’s appearance among Modern Orthodox Jews, as told in this Orthodox Forum volume, makes for a bracing read. The subheadings of one critical contribution sound like a negative psychological assessment: “Superficiality,” “Excessive Emotionalism,” “Selfishness,” “Lack of Commitment,” and “Confusion of Priorities.” Some essays do come not to bury Neo-Hasidism but to praise it. The forum gathering, so I have been told, included testy exchanges and fervent testimonials. An article published in the Yeshiva University student newspaper following the conference complained of the “embarrassingly biased and cynical tone, as well as its remarkably poor timing at a moment when neo-Hassidut had finally gained some acceptance in the broader community.”

The first task of Contemporary Uses is to consider whether traces of Hasidic thought are somehow present within Modern Orthodoxy’s largely misnagdic heritage. Indeed, some twentieth-century litvishe thinkers engaged with Hasidism, including Yeshiva University’s own Rabbi Soloveitchik, who occasionally drew on Chabad thought, and Rabbi Norman Lamm, YU’s recently deceased, long-serving president, who had a deeper interest in Hasidism and edited an important anthology of primary Hasidic texts. Still, no one could claim that Soloveitchik or Lamm brought the spice and spirit of Hasidism to their religious lives or those of their students, say by engaging in visibly ecstatic prayer or telling paradoxical tales. And so the question of genealogy haunts the introductory essay by Shlomo Zuckier as he tries to define Neo-Hasidism, plot its American Modern Orthodox advent, and uncover antecedents, all while wondering if it is good for the Jews.

Against doctrinal dangers, Zuckier argues that whatever its merits and demerits, Neo-Hasidism is a legitimate Modern Orthodox phenomenon worthy of discussion at the forum. This entails detaching it from non-Orthodox predecessors, which was easily accomplished by gatekeeping forum participants, and finding well-groomed Orthodox ancestors, a more difficult task. Zuckier’s instinct is largely correct: one cannot draw a straight line from Buber, Zeitlin, and Schachter-Shalomi to Weinberger, Weinberg, and Rosenfeld. Yet the excision of the Neo-Hasidic prehistory means largely ignoring indirect connections, such as the rise of Carlebachian “Happy Minyans” in Modern Orthodox synagogues over the last forty years or the resonance of Heschel’s critique of pan-halakhism. It’s also a missed opportunity to uncover a kind of Neo-Hasidic ritual grammar that takes on new forms, depending on the social and religious contexts.

In search of an Orthodox forebear, Zuckier invents one in Ahron Marcus, an observant German Jewish intellectual born in 1843 who, after a crisis of faith, enthusiastically embraced Hasidic life and wrote an early history of Hasidism. Zuckier pads Marcus’s CV, suggesting that Gershom Scholem spoke approvingly of his work (in reality, Scholem was highly critical of Marcus’s hagiographical writings). More problematically, though instructively, Zuckier fails to realize that Neo-Hasidism does not entail the total conversion of non-Hasidim to the Hasidic movement. Conversion has accompanied Hasidic history from its origins, swelling its population with newly inspired common folk and studding it with some A-list converts. In the end, what turns out to be Neo-Hasidism’s defining characteristic is the complex, twirling choreography that non-

Hasidic Jews make toward, away from, and sometimes in concert with Hasidism.

This dance is meticulously documented in the collection’s two standout contributions, a piece of intellectual cartography by Israeli sociologist Shlomo Fischer and a well-constructed work of anthropology by the late American anthropologist David Landes. Fischer focuses on three fascinating and seemingly quite distinct Israeli Neo-Hasidic rabbis—Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg (known as Rav Shagar, an acronym of his name), a rabbinic scholar who consulted every work of postmodernism that had been translated into Hebrew (not many) in his efforts to find a cure for his religious-Zionist angst; Rabbi Menahem Froman, an off-the-grid utopian sage who envisioned a radical, religiously based peace with his Palestinian neighbors; and Yitzchak Ginsburgh, the rebbe of the West Bank’s “hilltop youth,” who uses kabbalistic concepts to construct a fiery and dangerous ethnonationalism. Brilliantly, Fischer shows how each of these Israeli Neo-Hasidic figures offers a different but equally expressionist reaction to religious Zionism’s spiritual forbearer, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook.

For his part, Landes embedded himself among a group of Yeshiva University students as they established a small and informal Neo-Hasidic fellowship during a semester break. Landes lets his subjects speak for themselves, giving us access to their hopes and disappointments. We hear of desperate Purim wanderings, revelatory New York City parking miracles, spontaneous midnight pilgrimages to the grave of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and the collective’s preferred term for skeptics of Neo-Hasidism: “snags”—short for Hasidism’s erstwhile enemies, the misnagdim. Landes’s piece reminds us that the new Neo-Hasidism is just as much an experiential development as it is an intellectual one. It is more lived than it is learned. Neo-Hasidism provides these young Modern Orthodox seekers with a way into the drama of spiritual longing and an inspired release from dogmatic rigidity.

This religious eros and postmodern ethos are realized in the Neo-Hasidic indie band Zusha, named after an early Hasidic master fondly recalled for his simple, childlike holiness. While Zusha the sage was born in the rustic Ukrainian village of Anipoli in 1718, Zusha the band was founded in 2013 by three young men who grew up in the Modern Orthodox strongholds of Teaneck; Riverdale, New York; and Silver Spring, Maryland. All caught the Hasidic bug while attending college in New York. Nowhere near as famous as rock stars of the conventional Hasidic and Orthodox worlds like Lipa Schmeltzer and Mordechai Ben David, the group has nevertheless achieved quieter, and in some ways wider, recognition, with two albums reaching Billboard’s World Music top ten and a song appearing in the trailer of an award-winning independent film. The band is led by Shlomo Gaisin and Zach Goldschmiedt, who with their infectious smiles and unruly beards, large black hats and long coats, formfitting pants and big boots, look as if their namesake rode his wagon from Anipoli into Brooklyn, stopping along the way to be outfitted at Urban Outfitters.

A comparison to Matisyahu, who catapulted into and out of fame as a Lubavitcher singer, is tempting but misplaced. Apart from the obvious differences in fame and fortune, Matisyahu’s sound is a cross between reggae, rap, and beatboxing, with little Jewish musical influence. At the core of Zusha’s music lies the Hasidic niggun, which Gaisin and Goldschmiedt studied seriously and have taken in new directions. Aside from the non-Hasidic instrumentals, which showcase luscious piano, guitar, ukulele, and some other strings, Gaisin’s heartfelt raspy take on traditional Jewish vocalization—the “ayayays,” “oyoyoys,” and “yububums” of Ashkenazi scat singing—brings unanticipated freshness to their musical heritage.

More productive comparisons can be made to Shlomo Carlebach’s folksy simplicity. Zusha’s reliance on easy minor-chord progressions executed on acoustic instruments is as beloved among the band’s millennial and Gen-Z fan base as it was by Carlebach’s boomers. Zusha is also influenced by more recent non-Jewish musicians, especially the indie-folk singer Sufjan Stevens. Although Zusha’s songs do not have anything like Stevens’s theologically pregnant lyrics—their lyrics, when they have them, are constructed from short phrases taken from classical Jewish and Hasidic sources—one can still discern a similar attempt to make religious sense of a world in which God seems at times pulsatingly immanent and at other times achingly distant.

Their new EP, Cave of Healing, has just six short, prayerful songs and is a COVID-19 album through and through. One of the tracks incorporates the musical voice notes that Gaisin and Goldschmiedt would send each other after the shutdown had disrupted their regular work rhythms. The first song invokes the saving grace of forefathers, another is a plea directed at the prophet Elijah, while a third expresses the awareness that God ultimately runs the world. The album’s final song, “Lama Ata Bosh” (Why Are You Shy?), is a quiet anthem with soaring strings that shifts the direction of supplication away from God and toward the person praying. Its few lyrics are taken from the biblical commentator Rashi, who explains that when Aaron the High Priest was embarrassed and fearful to step up to inaugurate the divine service in the tabernacle, his brother Moses prodded him, saying, “Why are you shy? Approach the altar!” It is a relatively obscure moment in the history of Jewish interpretation but one that resonates now, when it’s not entirely clear if it’s a good idea to come out of our caves.

Like all music, Zusha’s songs are best experienced not on AirPods while sheltering in place but live and among men. Indeed, the band got its start playing in living rooms, shul basements, and synagogue social halls—often alongside Neo-Hasidic teachers like Joey Rosenfeld—and came to wider attention after performing shows at cramped Lower East Side venues such as the Bowery Ballroom and the Mercury Lounge and at community events like the Sixth Street Community Synagogue’s epic Purim party. Sound quality turns out to be less important than the social effervescence that comes with congregating in small spaces to hear soulful music.

In interviews, the group has joked that people often erroneously assume “Zusha” is Gaisin’s name rather than the band’s. It’s a funny mistake, one that subtly recalls the best-known Zusha tale, here in Martin Buber’s telling:

Before his death, Rabbi Zusha said, “In the coming world, they will not ask me: ‘Why were you not Moses?’ They will ask me: ‘Why were you not Zusha?’”

Part of the genius of early Hasidism was the freedom it gave adherents to dig deep into their souls and chart a unique spiritual path. The same can be said for today’s Neo-Hasids, so that the question of “who are you?” is not just a skeptical query posed by Teaneck householders but one that animates this new generation of Modern (or post-Modern) Orthodox Jews.

The journey takes a lifetime and can involve painful transformations and inspired reimaginations. One may sail, as Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are puts it, “in and out of weeks and through a day,” yet the quest is ultimately one of self-discovery “into the night of [one’s] very own room.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

I Have Come to My Garden

Without the Torah, says Rabbi Akiva, we would still be able to discover all its truths by delving deeply into the words of the Song of Songs.

The Lost Textual Treasures of a Hasidic Community

The Regensburg Library at the University of Chicago contains a catalogue of markings and stamps from books saved from Nazi destruction. One such stamp comes from the library of the Karlin-Stolin Hasidim, a collection that might contain the most valuable manuscript for understanding the roots of Hasidism. But where is it?

The Rebbe and the Professor

After the war, the great Jewish historian Salo Baron wrote to Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, for help with his work on the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction. As Hannah Arendt suggested in a side note to Baron, the commission probably wasn't “kosher” enough for Schneersohn, but their exchange illuminates a dark historical moment.

Quarried in Air

Sefer Yeṣirah is the most influential Jewish book you never heard of. Indeed, it has been argued that early commentaries written on the book tilled the gnostic soil out of which sprouted the tree of Kabbalah.

alfred marcus

very cool article thanks

[email protected]

SUPPRESSION AND CONFIRMATION OF DOUBT

Suppression of doubt is tyranny,

its confirmation non-dumbstriking irony,

intended to be by a hearer ne-

omorphized, read as glyphs of metahierony.