Counting Jews

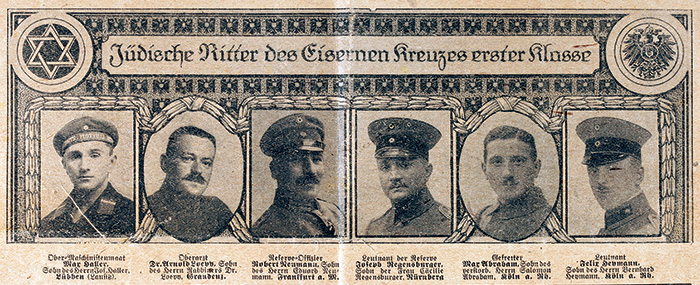

More than 12,000 German Jews died fighting for their country during World War I. It’s an astonishing figure given that there were only 550,000 German Jews at the time. (In Israel’s most costly war, the War of Independence, it lost around 10,000 soldiers and civilians out of a population of roughly 650,000.)

Nonetheless, in late 1916, the German army undertook a Judenzählung (“Jew count”) of serving soldiers to see if Jews were doing their part, yielding to widespread suspicion that they weren’t. This was a deep blow to German Jewish pride and is often described as a cultural turning point for German Jews. Of course, more was to come. After Germany’s defeat in 1918, Jews were accused of having “stabbed it in the back,” along with antimonarchists, socialists, and other radicals.

German Jews’ efforts to memorialize their fallen soldiers were the subject of Tim Grady’s highly informative first book. In his new and somewhat troubling book, A Deadly Legacy: German Jews and the Great War, he moves beyond battlefields, war memorials, and commemorative ceremonies to examine the role of all German Jews in the course of World War I. Grady’s account overlaps with conventional wisdom, but it has a much sharper edge. He highlights the ways in which “Jews and other Germans” (a phrase that he uses frequently) started out as war enthusiasts. Beyond that, he describes many ways in which Jews did their part to contribute to or support Germany’s worst excesses. And he doesn’t see the “Jew count” as a major turning point. Above all, in contrast to most historians, he focuses on the ways in which German Jews eventually became victims not just of vicious Nazi prejudice but of dangerous tendencies that they themselves had earlier aided and abetted. The way he makes this controversial case merits careful attention.

Grady provides a vivid account of the “early months of the war when Jews and other Germans often let their patriotic spirit run wild.” If German Jews had an additional, specifically Jewish reason for welcoming the outbreak of war, it was the fact that it pitted their country against the worst oppressor of their fellow Jews: Russia. “‘We are fighting,’ stated one German-Jewish publication, ‘to protect our holy fatherland, to rescue European culture and to liberate our brothers in the east.’” On this score, even the Zionists—a small minority of German Jewry—could eagerly join in: Their“main newspaper, the Jüdische Rundschau, declared, the Russians ‘will be taught a lesson.’ ‘Revenge for Kishinev,’ it cried.”

The Jewish-born but entirely deracinated Ernst Lissauer (Stefan Zweig described him as “perhaps the most Prussian or Prussian-assimilated Jew I knew”) poured out his wrath in a different direction shortly after the outbreak of war. His notorious “Hymn of Hate Against England” explicitly forswore hatred of Russia or France but—with a vehemence at which Grady only hints—portrayed England as being “full of envy, of rage, of craft, of gall” as Germany’s odious foe. This poem briefly became a sort of national anthem and even earned Lissauer the Order of the Red Eagle from the kaiser. (Grady traces Lissauer’s hyperpatriotism, in part, to the fact that the army rejected him on health grounds.)

After describing the murderous conduct of the Germans in neutral Belgium, which they overran at the very beginning of the war, Grady notes dryly but pointedly that “[s]ynagogue sermons often talked not of the sorrow of war but of its elemental power. Their focus was not on the destruction of Belgium but on the soldiers who had carried ‘the German flag from victory to victory.’” And it was not only run-of-the-mill Jewish leaders who fell short. Grady observes:

If Belgian women were amusing themselves by “poking the eyes out of wounded German soldiers,” as Martin Buber complained, then it was surely the Belgians rather than the Germans who were responsible for inhuman savagery.

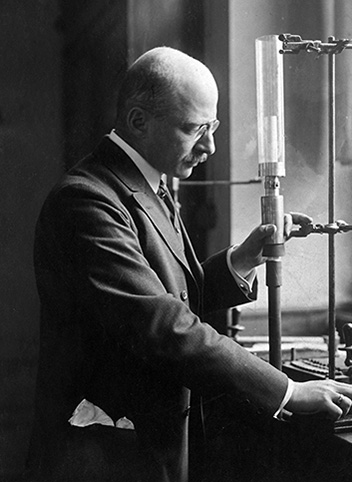

In 1915, Germany became the first country to use chemical weapons in combat when it released chlorine gas against the French line at Ypres, and it made extensive use of such weapons in the following years. Grady’s discussion of the Jewish role in these atrocities focuses on one man, the brilliant Jewish-born (but converted) chemist Fritz Haber. Grady highlights both the importance of Haber’s role and his zeal.

Throughout the development of this weapons programme, it was Haber, rather than the military, who pushed the technology forward. Haber arranged the experiments, won the backing of the army and even went to the battlefield to oversee the installation of the gas equipment. Such was his commitment to this new form of warfare that he put military success before his own family life. Soon after the first gas attack, Clara Immerwahr, Haber’s wife of twelve years, shot herself with her husband’s service pistol. The reasons for her suicide remain unclear. Nonetheless, looking back on events, it appears remarkable that the very next day Haber decided to travel to the Eastern Front to arrange further rounds of gas attacks.

Grady is careful to place all of this in perspective, however. “Despite Haber’s belligerence, German Jews were never the main cheerleaders of this aspect of total war.” On the other hand, he writes, “like all other Germans, they gave their tacit backing through either quiet acquiescence or, on rarer occasions, direct support.”

When Reinhold Seeberg, a professor of Christian theology in Berlin, published in June 1915 a petition calling “for both large-scale annexations and the Germanisation of land in the east,” several prominent German Jews signed it. The conservative publicist and academic Adolf Grabowska (Jewish-born but a convert to Protestantism) “was particularly vociferous in his support of eastern expansion.” Davis Trietsch, a prominent Zionist, called for expansion in the east, the west, and Africa, “while Max Warburg, Walther Rathenau and other prominent German-Jewish businessmen advocated economic dominance.”

By the winter of 1915–1916, Germans, including German Jews, “started to look around for an explanation for the military’s failure to end the war” and increasingly tended to vilify and mistreat “the others” whose conduct supplied one. Grady’s primary example of such deplorable behavior seems to be the Germans’ illegal exploitation of foreign laborers: “Plans to force Belgians and Eastern Europeans to work for the German war effort suggested a cruel and uncaring stance towards other population groups.” The Jews who played a part in drawing up and implementing these plans included industrialists such as Walther Rathenau, legislators such as Georg Davidson and Max Cohen-Reuß, and the Zionist Franz Oppenheimer. Grady sees further evidence of the wrong stance toward other population groups in the participation of German Jewish anthropologists in research projects “based on a distinct sense of national superiority” and focused on African, Asian, and Eastern European captives in German POW camps.

Grady’s succinct retelling of the story of the “Jew count” clearly shows how disturbed German Jews were by it. Among others, he cites the case of Ernst Simon, who had patriotically volunteered for duty and been wounded at Verdun but in the aftermath of the count felt increasingly alienated from his country (and eventually migrated to Palestine, where he became a prominent teacher and religious thinker). But Grady rejects the idea that Simon was typical. While “[i]t has become almost a given that the military’s census permanently altered German Jews’ relationship to Germany,” he writes, people like Simon were “the exception rather than the rule.” The census and German setbacks “may have wiped some of the lustre from the fight” for German Jews, “but their desire to see Germany emerge victorious was undiminished.”

While this remained true of most German Jews, there were some who turned, in time, against the war, such as Martin Buber, whose change of heart does not seem to have registered much outside of the Jewish world. More significantly, there were highly visible Social Democratic politicians, such as Hugo Haase and Kurt Eisner, who supported and even led strikers calling for “‘more and better food,’ peace and democratic reforms.” Unrepresentative as they were of German Jews in general, they “seemed to provide further evidence for those who believed that German Jews were somehow inextricably linked to revolutionary, unpatriotic behavior.” When Haase, Max Cohen-Reuß, and their colleague Oskar Cohn spoke out in the Reichstag early in 1918 against the annexationist Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, it “further provoked anti-Semites back to life.”

It is these developments that Grady seems to have in mind, primarily, when he observes that the postwar right-wing notion that Germany had been stabbed in the back was “not simply plucked from thin air, but rather stemmed from the actions of Jews and other Germans during the final months of the conflict.” But there is something else as well: The myth “had actually first been propagated by a broader spectrum of Germans, including several German Jews, during the war. Georg Bernhard, Walther Rathenau, and Max Warburg had all added elements to the ‘stab in the back’ myth with their response to the strikes of January 1918 or to the armistice later that same year.”

Together with other Germans, then, Jews left a number of “dangerous legacies” for their country. In contributing to the “specifics of Germany’s First World War,” they unwittingly played a part in establishing “the foundations for Hitler’s eventual path to power.” Ironically enough, they “were gradually excluded from the legacies that they themselves had earlier helped to shape” and subsequently either forced into exile or killed.

Grady does not intend to say that the Jews reaped what they sowed, only that they reaped what some or even most of them together with others helped to sow—which is still a grave enough judgment, if not exactly an accusation. One can’t say that it is utterly unwarranted, but it is overblown. As Grady demonstrates, German Jews were surely caught up in the wave of war enthusiasm, persisted for the most part in supporting the war effort to the end, and by and large acquiesced to Germany’s most egregious misdeeds. And a number of individual Jews bore a considerably greater degree of culpability. Still, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that some of the worst things that Grady repeatedly attributes to “Jews and other Germans” were really the work mostly of other Germans—and some Jews. Nor are the Jews in question always as representative or as numerous as his account, at first glance, makes them appear to be.

One has to wonder, to begin with, about Grady’s regular identification of converts from Judaism as Jews. It is true, as he observes, that in imperial Germany Jews often became Christians not for spiritual reasons but in order to become “more German” and that many of them “retained a deep connection to their Jewish identities long after they had been baptised.” But can one on these grounds count any ex-Jew as a Jew, without further explanation, as Grady generally seems to do? I am not entirely sure that this is how he is counting Jews, but if it is, he doesn’t do it with perfect consistency. One of the journalists he adduces as evidence of German Jewish hyperpatriotism is Paul Nikolaus Cossmann, who was a convert, as Grady notes, to Catholicism. Later in the book, however, after noting how the “defining image of the infamous ‘stab in the back’ myth” had first appeared in 1924 on the cover of Cossmann’s journal, Grady observes that a Munich Jewish lawyer “suggested that ‘the Jew’ Cossmann had invented the ‘stab in the back’ myth.” Grady goes on to say that this lawyer was wrong to label him as a Jew since “Cossmann had converted to Christianity in his mid-thirties.” But either Cossmann counts as a Jew or he doesn’t, and if he doesn’t, why does the inventor of chemical weapons and Protestant convert Fritz Haber count?

Actually, as Grady observes, even Cossmann did not specifically identify Jews as the people who had stabbed Germany in the back; he accused socialists. Toward the end of the book, Grady refers vaguely to several Jews who propagated the “stab in the back” myth, but earlier in the text, he names only two more: the parliamentarian Ludwig Haas and the converted banker Georg Solmssen. His claim that three other Jews—Georg Bernhard, Walther Rathenau, and Max Warburg—added elements to this myth is not really substantiated. All he shows is that these men remained diehard supporters of the war effort to the bitter end and beyond.

Similarly, when Grady documents the participation of Jews in anthropological studies tinged with racism, he speaks of “many German-Jewish academics” who showed remarkable enthusiasm for such work. After identifying an artist and a sculptor on a racist project, he introduces, with the word “finally,” his third example, the photographer Adolph Goldschmidt. Three, one has to say, is not that many (and there aren’t more lurking in the footnotes).

Grady, it is clear, sometimes strains to make his case. But that doesn’t mean that he has no case to make. Among the more than half a million Jews and converts from Judaism living in Germany during the war, there were certainly a significant number of individuals who, as he shows, placed their country “über alles” and followed up on their convictions in deplorable ways. Some of them later concluded that the things they did had helped lay the foundations for Hitler. In his epilogue, Grady cites the ex-soldier and great medieval historian Ernst Kantorowicz, who said that both during World War I and afterwards, “fighting actively, with rifle and gun,” he had “prepared, if indirectly and against my intention, the road leading to National-Socialism.” Kantorowicz had better reason than most other Jews to consider himself blameworthy: He had, as Grady observes, joined the violent right-wing paramilitary Freikorps after the war. But we should be wary of attributing a comparable measure of guilt to too many of his German Jewish contemporaries.

Suggested Reading

A Foreign Song I Learned in Utah

Despite all of Bob Dylan’s subterfuges, disguises, and costume changes, he really was a child of the American heartland. Winning the Nobel Prize might actually be his most Jewish achievement.

In Brief, Winter 2011

Judaism and Americanism, Young Tel Aviv, Psalms in the Arctic, Haym Solomon, and Funnyman

High Threshold

Visitors to the Hazon Ish's house would sometimes enter through the window; the venerable sage occasionally left home the same way. “A window,” the Hazon Ish reassuringly explained, “is in fact just a door with a high threshold.”

A Stone for His Slingshot

In 1948 screenwriter Ben Hecht lectured “a thousand bookies, ex-prize fighters, gamblers, jockeys, touts,” and gangsters on the burdens and responsibilities of Jewish history. The night at Slapsy Maxie’s was a big success, but the speech was lost, until now.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In