A Foreign Song I Learned in Utah

What could be more Jewish than winning the Nobel Prize? According to a recent accounting, of the 850 recipients since the prize’s inception, 181 (or 21.294 percent) have been Jews. If the Nobel Prize were the electoral college, Jews would be the state of Wyoming, represented way beyond their actual size in the population.

So when Bob Dylan became the surprise winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature on October 13, 2016, it could be seen as further proof of his Jewishness. And in fact, just about every Jewish newspaper, magazine, and website, from the left-leaning Forward to the right-careening Jewish Press, dutifully noted the ethno-religious connection. The association was more or less reflexive. Everybody knows that Dylan is a Jew—even if he did once convert to evangelical Christianity. And gone are the days when an Elderhostel lecturer might try to simulate hipness by revealing to his assembled class of alte kakers that the now septuagenarian enfant terrible of rock was actually born Robert Allen Zimmerman.

Still, what beside his birth name is really Jewish about him? Ask that and you’ll get a standard array of answers. It’s his questioning pose, some say, which echoes the interrogative Jewish sensibility (Dylan’s first hit, “Blowin’ in the Wind,” is comprised of nine unanswered questions). Or it’s his prophetic voice, others insist, perpetually challenging authority in lyrics drenched in Old Testament imagery (his “All Along the Watchtower,” for instance, strongly evokes Isaiah 21). Or—in an argument that’s as hard to refute as to prove—it’s his very constructed identity, his Bob Dylan-ness, an intricate garb of concealment behind which the modern-day Marrano occasionally winks in bemused acknowledgement of his authentic Semitic self.

Singer Dave Van Ronk, a mentor to many younger folk performers in the Greenwich Village scene of the early 1960s, relates a charming story of young Dylan’s inadvertent self-exposure while relaxing after a gig in the Gaslight Cafe. “Dylan was telling everyone in New York that he was from New Mexico, an orphan who had been on the road for years.” In fact, this was only one of Dylan’s fabrications. By that time he had already posed as the Okie replicant of his early musical hero Woody Guthrie; as a hobo who’d shared a boxcar with the likes of blues singer Big Joe Williams; as a “circus hand, carnival boy, road bum, musician, and many other roles in what have come to be called the Dylan myths,” as early biographer Anthony Scaduto catalogued. Of course, such subterfuges were hardly alien to the contemporary folk scene that Dylan had noisily barged in on. Guthrie himself, though certainly an Okie, was no peasant but the scion of a well-off and politically connected family. Woody’s disciple and another of Dylan’s mentors, the cowboy singer Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, is a more telling precedent. As Van Ronk notes, Dylan had no idea that Ramblin’ Jack’s father was a Jewish doctor from Brooklyn who shared the name Abraham with his own father. “As far as Bobby knew, Jack Elliott was absolutely gold-coin goyisha cowboy. In the course of the conversation it came out somehow that he was Elliott Adnopoz, a Jewish cat from Ocean Parkway, and Bobby fell off his chair. He rolled under the table, laughing like a madman.” To Van Ronk, Dylan’s (over)reaction provided clear proof of his own Semitic origins. “We had all suspected Bobby was Jewish, and that proved it.”

If Dylan’s Jewishness was an open secret, at least within his close circle, he still insisted on maintaining the pretense of being a Gentile cowboy, or poor farmer, or hillbilly. This was not merely a ruse born of an assimilatory impulse; it was a professional necessity, since the type of folk music the early Dylan performed was very much in the vein of Guthrie, and Williams, and Elliott. Dylan is often described as a revolutionary, but in fact his early records were surprisingly conservative, sticking largely to an Anglo American conception of folk song with occasional forays into Negro blues—though distinctly of the country rather than the urban variety. What captivated early listeners was, first, his apparent total mastery of that style, veritably embodying and not merely emulating the Okie persona (to a remarkable extent he managed this even physically, as the cover of his record The Times They Are a-Changin’ attests, despite a visage that would later be categorized as “obviously” Jewish); and second, the convincing manner in which he extended and updated that same Anglo folk form when he began writing his own songs. The remarkable compositions on his 1963 breakthrough album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, updated American folk music’s traditional practice of topical social commentary, replacing 1930s images of striking workers and dust bowl migrations with fresh ones of freedom rides (“Oxford Town”), nuclear destruction (“A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall”), and the military-industrial complex (“Masters of War”). Dylan’s convincing embodiment of a rural Appalachian persona lent these performances a powerful if oddly anachronistic flavor—as if the musical sensibility of the New Left derived from the middle American heartland.

Certainly, there were other roads he could have walked down. Contemporary folk artists like Theodore Bikel were known exponents of Yiddish and Hebrew song. Jewish song, in fact, comprised a more or less standard component of the American folk music scene dating back to Paul Robeson’s 1940s performances of “The Hassidic Chant of Levi Isaac of Berditchev” and the Yiddish “Partisan Song” of the Warsaw Ghetto. In 1950 The Weavers enjoyed a two-sided hit with Lead Belly’s “Goodnight Irene,” backed by a rousing version of the Zionist tune “Tzena, Tzena.” And even as late as the early 1960s, the black singer and civil rights activist Nina Simone (who would later record a number of Dylan compositions) continued the tradition by recording and then performing live “Eretz Zavat Chalav u’Dvash” at Carnegie Hall. The closest Dylan came to dabbling in this “folk songs from many lands” tradition was his parodying of the subgenre in the comical “Talkin’ Hava Negeilah Blues,” performed as early as 1961 in a style so deliberately un-Jewish that it really sounded like “a foreign song I learned in Utah” (replete with yodel), as Dylan’s tongue-in-cheek introduction would have it.

Otherwise, Dylan seemed to completely bypass the ethnicizing component of traditional American folk performance. When he did finally leave his Woody Guthrie pose behind it was not to adopt a Jewish or other national style but rather to shift his orientation from rural to urban, from acoustic to electric. The episode in which this transformation fully crystallized—Dylan’s (partly) electric performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival—has been so frequently rehearsed, not to say mythologized, that it hardly bears repeating. Suffice it to say that many of Dylan’s fans really did see his coming out electric as a fully fledged betrayal, a sell-out to the market for shallow youth pop music. And some of those fans really did scream “Judas!” Jewish Dylanologists (almost a redundant term) are not entirely wrong to hear the Judas charge as an ugly outing of Dylan’s Jewishness. While the distinctly Judaic references in his subsequent vast musical output remain paltry, it could even be argued that the metamorphosis from hick to slick and clod to mod did entail the disclosure of a more authentic hipster Jewish self behind the pose of country rube, with lyrics now marked less by earnest youth protest (“your sons and your daughters are beyond your command”) than by the surreal subversion of American middle class normality (“you never understood that it ain’t no good to let other people get your kicks for you”).

Still, this argument overlooks the fact that despite all of Dylan’s subterfuges, disguises, and costume changes, he actually was a child of the American heartland. Why, one might wonder, should his definite Jewish origins contradict his rural Midwestern ones? While biographers routinely invoke his backwater hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota, the difference it made in defining his kind of Jewishness or his musical identity is typically ignored.

Hibbing was a mining town in the Minnesotan far north. Like many such places it had its smattering of Jews that constituted the bulk of its shopkeeping class (Abe Zimmerman, Dylan’s father, owned a furniture and electronics store with two of his brothers, Maurice and Paul). Yet the wartime booms Hibbing experienced could not overcome its sheer physical and cultural isolation. Enveloped by hills and dense forest, the town felt paralyzed during long winter months (“in the winter everything was still, nothing moved,” Dylan recalled). Hibbing’s small Jewish community was similarly forlorn. Historians have focused heavily on 20th-century big-city Jews; small and isolated settlements like Hibbing rarely make it onto their maps. Life in such places seems to have had a dualistic quality: a high degree of social segregation combined with high levels of cultural assimilation.

Bobby Zimmerman had a bar mitzvah, attended Wisconsin’s Herzl Camp, and was surrounded by an extended yet close-knit Jewish family. But the kind of reference points and ethnic connections that city Jews, no matter how alienated, possess as a birthright were largely absent from his youth. He developed a strong sense of his distinctiveness from his environs but lacked the consolation or crutch of an ethnic cohort to cushion his estrangement. Part of this estrangement was expressed, as several acquaintances during these early years attest, by a discomfort with his Jewish origins. Bob’s difficult relationship with his father, Abe, derived in part from the latter’s stern and disapproving demeanor but also from his mercantile values as a small shopkeeper, ones his son apparently found distasteful. Highway 61, the setting for the akedah redux in his 1965 song “Highway 61 Revisited” (“God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son’”), runs right through the songwriter’s Duluth birthplace.

It is not a romanticization to say that the Jewish vacuum of his adolescence was filled not just with the country and western music that Dylan imbibed on AM stations throughout those frozen Hibbing months, but by a genuine body of American folk imagery absorbed from his surroundings. “The madly complicated modern world was something I took little interest in,” he recalled in his arresting memoir Chronicles: Volume One:

It had no relevancy, no weight. I wasn’t seduced by it. What was swinging, topical and up to date for me was stuff like the Titanic sinking, the Galveston flood, John Henry driving steel, John Hardy shooting a man on the West Virginia line. All this was current, played out and in the open. This was the news that I considered, followed and kept tabs on.

Folk songs, Dylan remarked, “transcended the immediate culture.” They represented “a reality of a more brilliant dimension” comprised of “archetypes,” of “life magnified” and “metaphysical in shape.”

So it’s often forgotten that while Dylan went electric in 1965, he went acoustic again in 1967. Two years later he recorded a country and western album with megastar Johnny Cash, and he has continued to record country, folk, blues, and other heartland musical forms right up through the present. While in the eyes of many critics the mid-1960s “electric” years mark Dylan’s artistic peak, this phase’s entwining of surrealist poetry with heavy amplified rock doesn’t typify his musical career as a whole. If there is any truth to the notion that Dylan’s mid-60s urban shift represents a Judaization (or Judas-ization) of his sensibility and allegiances, it remains a fact that he wasn’t a big-city Jew for very long.

There is another “Jewish” ambiguity—this one in regard to Dylan’s relationship to the mainstream tradition of American pop music songwriting. Generically labeled Tin Pan Alley, the cream of which has come to be called the Great American Songbook, this monumental body of work includes the contributions of such figures as Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Cole Porter, Duke Ellington, Hoagy Carmichael, and Fats Waller. Half the names on this list are Jewish ones, an over-representation that extends from the Alley’s turn-of-the-century origins to its later Brill Building incarnation of the early 1960s, where almost all of the writers—including Jerry Leiber, Burt Bacharach, Carole King, Jeff Barry, and Neil Diamond—were Jews. When Dylan first started making his mark as a songwriter, at the very moment Brill was bustling, he made it clear that his goal was nothing less than to demolish this commercial hit-making machine. He spoke disdainfully of the “milk and sugar” and “empty pleasantries” of contemporary American pop that was manufactured by “workhorses,” cogs in the songwriting “factories” of midtown Manhattan, and juxtaposed its saccharine concoctions to authentic expressions of indigenous rural, blues, and country folk.

How much of Dylan’s dislike of the Alley reflected the small-town Midwestern Jew’s suspicion of his city cousins? Well into the 1980s he boasted of having “put an end” to Tin Pan Alley, and even when he was honored in 1986 by ASCAP, its professional association, he accepted the lifetime achievement award, he insisted, on behalf of the excluded folk musicians like Hank Williams, Jimmy Reed, and Muddy Waters. “We never claimed to be as good as Johnny Mercer or Hal David or Jerome Kern or any of those people. We just used that medium to write what we were feeling,” he said. Nevertheless, in an interesting late-career twist Dylan finally began to explore the Great American Songbook for himself, releasing two albums of his affecting if scratchy-voiced renditions of such chestnuts as “Autumn Leaves,” “Some Enchanted Evening,” and “Polka Dots and Moonbeams.” He wasn’t covering these songs, he insisted, but rather “uncovering” them, exposing them not as “standards” to be preserved but as genuine folk songs to be interpreted. In this remarkable gesture, was Dylan finally laying claim to the songs of his people, the Tin Pan Alley tunesmiths writing songs on commission? Perhaps, but as with every effort to penetrate Dylan’s Jewish soul, in this case too there is no clear direction home.

No one has better analyzed Dylan’s “Jewish question” than the historian David Kaufman. His unfairly neglected 2012 book, saddled with the unfortunate title Jewhooing the Sixties, is comprised of four stimulating essays on the early 60s Jewish celebrity of Sandy Koufax, Lenny Bruce, Barbra Streisand, and Bob Dylan. (See Eitan Kensky’s review in the Spring 2013 issue of this magazine.) The Dylan chapter is a particularly subtle and astute performance. Kaufman begins by addressing the question of how important Jewishness is to Dylan’s role as an artist and public figure. His answer—given the actual dearth of positive evidence—is: not very. But Kaufman then moves on to a far more interesting question: Why then have so many Jews (and some non-Jews) invested such remarkable energy in uncovering Dylan’s Jewish core? The answer, according to Kaufman, is that Dylan’s prestige and mystique as a preeminent contemporary artist—especially if misleadingly understood as an artist of the counterculture—his very opaqueness, in fact, make him the perfect target for our muddled pursuit of modern Jewish identity. “In the end,” Kaufman asks, “might it be that Dylan’s assimilation is the Jewish behavior of his with which so many have identified?”

Kaufman suggests that the astonishing vitality of Jewish Dylanology exposes its function as seeking in Dylan’s work and life a usable Jewish present. This pursuit, bordering at times on obsession, a veritable Zimmermania, was not marginal to the shaping of the baby boom’s Jewish self-image but actually lay close to its core. It penetrated to some of the generation’s leading scholars of Jewish modernity, while also reaching Jews far beyond America’s borders, in Europe and especially in Israel where Dylan’s infrequent concert visits have been anticipated with near messianic expectation.

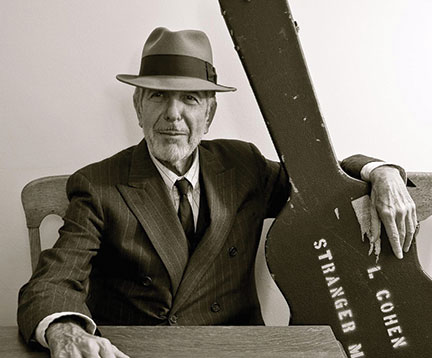

Yet in recent decades there has emerged a serious competitor to the status of our century’s premier Jewish icon and poetic sage. For this role, the recently deceased Leonard Cohen possessed many assets that Dylan himself lacked. More obviously learned in Jewish texts and far more effusive about his identification with the tradition, the rabbinic allusions found in a number of Cohen’s songs, from his famous “Hallelujah” to his own akedah song “You Want It Darker,” released just weeks before he died, do not require any extraordinary forensic-exegetical ingenuity to ferret out. Those who know really do know.

Unlike Dylan, moreover, Cohen came from the center not the periphery of Jewish life, raised in a place almost as cold as Hibbing but, from a Jewish perspective, its polar opposite. A scion of the Montreal Jewish establishment, Cohen’s family was an industrious mix of makhers and scholars. And if Cohen’s five-year seclusion in a Buddhist monastery parallels Dylan’s temporary Christian conversion, Jewishly speaking it’s a hell of a lot more palatable. The outpouring of eulogistic tributes from learned Jewish admirers lamenting the passing of Eliezer ben Nisan ha-Cohen (referring to him by the Hebrew name he liked his friends to employ) makes him appear at times like a great tzaddik who—to quote a Dylan lyric—“crossed over from another century” into our blessed present.

While Cohen’s reputation as a poet has been widely acknowledged, labeling Dylan one still raises eyebrows and even eye rolls from literary feinschmeckers. No wonder the Swedish Academy’s naming of Dylan as its 2016 laureate for literature was greeted with so much hand-wringing, discomfort, even outrage. Some grumbled that if a songwriter had to be granted the prize, it should have gone to Rabbi Cohen rather than to Reb Bob. This debate too will not be soon resolved. We can leave it then to the deceased to pronounce a final word on the living. When asked about his friend and fellow Jewish “rock poet” receiving the prize, Cohen, with characteristic grace, simply hinted at its redundancy, saying it was like “pinning a medal on Mount Everest for being the highest mountain.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On That Distant Day

Benjamin Netanyahu is back in the Prime Minister’s chair, but where are the factions who put him there taking Israel?

The Jewish Preview of Books—September 2018

A quick look at Jewish books being published this month.

The Homecoming

A 1977 Jerusalem Post article on Harold Pinter's visit to Israel was enticing but short on details. Pinter had just been to the Dead Sea (“hot!”) and Mount Masada (“high!”) and was planning to visit a cousin who lived on a kibbutz.

Words, Words, Words

The super sad truth about Gary Shteyngart's new novel.

gwhepner

The difference between Reb Bob, Jonathan Karp's Reb Bob, Bob Dylan, and Rabbi Cohen, his version of Leonard Cohen, who liked his friends to call him Eliezer ben Nisan HaCohen, is that Reb Bob is and always has been an authentically assimilated Jew who never fakes it with pretentious misquotations of Judaic texts, whereas by contrast Leonard Cohen was unfortunately an unconvincing replica of an apikores,though considered hallowed by a Hallejah chorus for whiich Jwes who're authentic should not stand. Bob is, as Leonard to his credit once implied, as real as Everest, since he's the highest mountain where kosher oxygen is not offered, whereas Leonard was, regrettably, an overrated, nebbishdicker literary kohanic faux feinschmecker.

gwhepner@yahoo.

gwhepner

The difference between Reb Bob, Jonathan Karp's Reb Bob, Bob Dylan, and Rabbi Cohen, his version of Leonard Cohen, who liked his friends to call him Eliezer ben Nisan HaCohen, is that Reb Bob is and always has been an authentically assimilated Jew who never fakes it with pretentious misquotations of Judaic texts, whereas by contrast Leonard Cohen was unfortunately an unconvincing replica of an apikores,though considered hallowed by a Hallejah chorus for which Jews who're authentic should not stand. Bob is, as Leonard to his credit once implied, as real as Everest, since he's the highest mountain where kosher oxygen is not offered, whereas Leonard was, regrettably, an overrated, nebbishdicker literary kohanic faux feinschmecker.

[email protected]