Was Lincoln Jewish?

In my Jerusalem neighborhood, there are three quiet streets named for historic Hebrew newspapers. Ha-Melitz (The Advocate), founded in 1860 in Odessa, fostered vigorous debate about social and political issues. Ha-Tzfira (The Clarion) began life in Warsaw in 1862 as an ideologically pareve marketplace of ideas, with an emphasis on science. Ha-Magid (The Storyteller), published in Lyck, East Prussia, specialized in news of Jews around the world, such as the following story of February 19, 1863:

Permit me a florid translation:

The ruler Abraham Lincoln, head of government of the Lands of the North (president [transliterated]) in America, during a recent visit of the learned rabbis, Messrs. Wise and Lilienthal from Cincinnati, and attorney (advocat) Martin Ligur [sic: the man’s name was Bijur] from Louisville, who had come to vent their spleen upon General Grant (see Ha-Magid No. 7), and ask him to reverse the evil decree issued by the general upon all the Jews in the territory of Tennessee, told them in the course of conversation, after promising to reverse the decree, that he (the president) sprang from the belly [lit. “bowels”] of Judah, and his forefathers were Jews; and these emissaries indeed report that the facial features of the president are evidence of his descent from the loins of the Hebrews.

The story of the “evil decree,” Ulysses S. Grant’s “General Orders No. 11” of December 17, 1862, aimed outrageously at “Jews as a class,” has been compellingly told by Jonathan Sarna in his sesquicentennial study, When General Grant Expelled the Jews. (Sarna has also coauthored a history called Lincoln and the Jews.) Sarna explains that Isaac Mayer Wise and his companions were on their way to Washington to protest—perhaps a hundred Jews were expelled, some of them speculators and smugglers—when they learned that Lincoln had revoked Grant’s order; they decided to continue their journey and thank him in person. Sarna quotes from the Hebrew account of the expulsion in Ha-Magid No. 7, but doesn’t identify its author or relate the astonishing scoop of yichus in Ha-Magid No. 8. Following that strange Lincoln story, the dispatch concluded with a litany of real and alleged Jewish notables in the armies of the South and North, and was signed only with the Hebrew letter vav.

It appears that Ha-Magid’s reportage about Grant was penned from afar by one Henry Vidaver, a young Warsaw-born, German-trained rabbi and Hebraist who had held a pulpit at Congregation Rodeph Shalom in Philadelphia, but fell out with community leaders and went back to Germany in 1861. His politics apparently had something to do with it: He was rooting for the wrong side. As Rabbi Morris B. Margolies of Kansas City unearthed in 1983, in an article for the journal Western States Jewish History, Vidaver had defended slavery and the Confederate cause in other stories he wrote for Ha-Magid. In 1863, he was sitting in Germany, pontificating on American Jewry as blithely as any long-distance blogger today. He could have read about General Orders No. 11 in a European newspaper and rehashed it in Hebrew for Ha-Magid. Margolies is silent on the Grant episode, leaving us to wonder: How did Henry Vidaver know what happened on January 7, 1863, when those Jewish leaders met Lincoln in the White House?

Barely two years later, the Civil War was over, Lincoln was assassinated, and Vidaver was back in the United States, serving as a rabbi in St. Louis. Now he wrote in Ha-Magid that Lincoln’s name “will be remembered eternally with love by all decent people.” Indeed Father Abraham became a saint for American Jews, a martyred Moses who revered the Bible. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who had thundered that Lincoln’s election was a national “blunder” and called him “a country squire who would look queer in the White House with his primitive manner,” now eulogized the slain president at Cincinnati’s Lodge Street Synagogue as “the chosen banner-bearer of our people, the Messiah of this country,” a man “whose greatness was in his goodness,” and crowned his encomium with a stunning revelation:

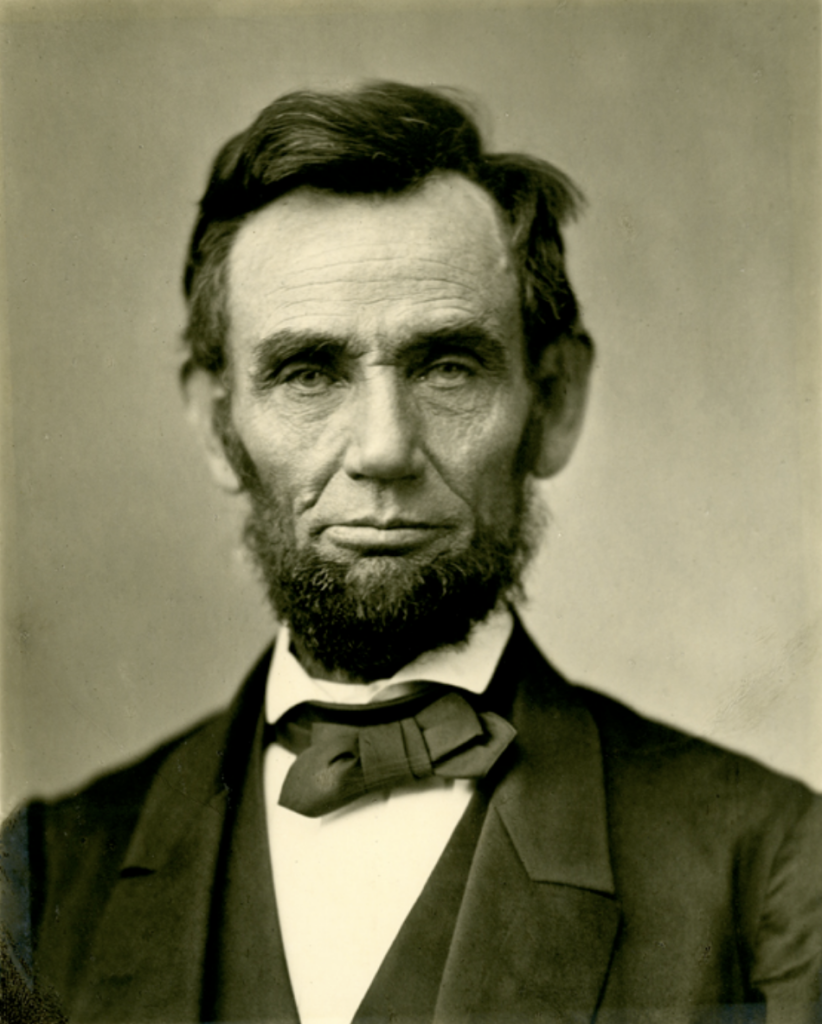

Brethren, the lamented Abraham Lincoln believed himself to be bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh. He supposed himself to be a descendant of Hebrew parentage. He said so in my presence. And, indeed, he preserved numerous features of the Hebrew race, both in countenance and character.

Character is one thing, countenance quite another: a euphemism for yiddishe punim, the nose in particular. Countenance is what enables seasoned Chabadniks to pick out Jewish pedestrians with staggering accuracy, and Rabbi Wise, it would seem, was likewise gifted. It was he who must have leaked the original story to Vidaver, as we learn from Bertram W. Korn’s canonical work of 1951, American Jewry and the Civil War. Korn, a Reform rabbi and scholar, began a chapter called “Lincoln and the Jews” by quoting Wise’s striking words, quickly adding: “There is no shred of evidence to substantiate Wise’s assertion. . . . [Lincoln] could not, however, have been any friendlier to individual Jews, or more sympathetic to Jewish causes, if he had stemmed from Jewish ancestry.” In a long footnote, the author alleged that although Wise, in his 1863 editorials about Grant, did not mention the conversation with Lincoln, “he did tell one of his colleagues, Rabbi Henry Vidaver of St. Louis, about it.” Korn helpfully identified Vidaver as “the American Correspondent for the Hebrew monthly HaMagid” (it was a weekly, but no matter.) “Wise’s assertion has been known to writers for a long time,” noted Korn, but “has not been given much weight in their writing about the mysteries of Lincoln’s background.” Besides, he ventured, “Wise may not have reported the conversation accurately, or may not have understood the meaning of the President’s remarks.”

There the learned consensus stands: Lincoln spoke to Wise metaphorically, and the Jewish roots are merely a tantalizing rumor, like Ulysses S. Grant keeping kosher. (Indeed, as Sarna shows, Grant contritely became a practicing philo-Semite in the aftermath of the affair, but there’s no proof his feelings extended to the kitchen.) And yet, if Isaac Mayer Wise, grand panjandrum of American Reform Judaism and founder of Hebrew Union College, said Lincoln looked Jewish, and took seriously his claim of Hebrew ancestry, why on earth haven’t dogged scholars picked up the bone of our bone and run with it? Admittedly, Wise’s credibility may have been blemished after he declared that oysters were both kosher and treif. But still—in the delicious pursuit of Jewish yichus, is any rumor ever too mere?

In this case, there may indeed be more to it. Educated speculation has it that Lincoln was of Melungeon stock, an ethnic melange possibly derived in part from Muslims and Sephardic Jews who landed with Spanish explorers in the American Southeast in the 16th century, and migrated to Appalachia. According to Elizabeth Caldwell Hirschman, professor of marketing at Rutgers University and author of the 2005 monograph Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America, not only Lincoln but also Daniel Boone was of Judeo-Melungeon lineage. “Anyone who looks at photographs of Abraham Lincoln,” she wrote, “is no doubt struck by his distinctively Semitic features.” Raised as a Protestant in Tennessee, Hirschman converted to Judaism after discovering her own Melungeon roots. Her intriguing book, alas, makes no mention of Lincoln’s remark to Isaac Mayer Wise in 1863.

How do we handle such material? Dismiss it as pseudoscholarship, mere clickbait for conspiracy buffs, or entertain the reasonable hypothesis of buried identity, awaiting further research? Let’s imagine that some futuristic DNA sleuth determines that Abraham Lincoln was mostly Anglo with a splash of Cherokee, but also a direct descendant of the Spanish kabbalist Abraham Abulafia. If I were a maggid in Hollywood, I’d be tempted to concoct a Da Vinci Code clone, with Oscar Isaac as the handsome Henry Vidaver, and a shattering climax in the bowels of the Lincoln Memorial. But seriously—will it sell?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Lost in America

Two new books, different in tone but matched in caliber, show Israelis making their way as best they can in America and in life.

The People of the Book – Since When?

A new book seeks to overturn everything we know about the history of the Talmud.

Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942.

On Re-Reading a Banned Book: Nathan Kamenetsky’s Making of a Godol

Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky spent years on an odd, brilliant biography of his father. The book was banned, and one leading haredi rosh yeshiva said he had forfeited his share in the world to come. Now it is an underground classic that costs $2,503 on Amazon.

David Cooper

At the time of the English expulsion in 1290 Lincoln, England had a sizable Jewish community most of whose members converted to Christianity. It is possible that one of President Lincoln's distant ancestors was a member of that community of English formerly Jewish Christians.