Mansions, Museums, and Magen Davids

“All that remains is the art,” writes James McAuley at the opening of The House of Fragile Things: Jewish Art Collectors and the Fall of France, an elegiac, beautifully written study of four interconnected French museums. All were houses originally owned by Jews whose descendants perished in Auschwitz. The houses they loved and objects they collected remained prized possessions of the French state. This fate is, simultaneously, both an acceptance of their refined engagement with European culture and a rejection of their inescapably Jewish selves. It was, in short, precisely what these Jewish patriots and philanthropists had wanted—and, at the same time, the very antithesis of what they had in mind. That paradox lies at the heart of McAuley’s elegant and moving book.

The Cahen d’Anvers, Camondos, Reinachs, and Rothschilds were immensely rich Jews who lived lives of luxury and privilege in the French fin de siècle and its aftermath. They were also Jewish business dynasties who came from (and belonged to) a strikingly cosmopolitan world. Count Louis Raphael Cahen d’Anvers was the French son of Belgian German parents who had married in Antwerp, where his mother’s Bischoffsheim relatives were prominent figures in the worlds of politics and finance. His wife, Louise Morpurgo, came from an Italian family whose business interests spanned the Mediterranean. A seductive woman with heavy eyes, her blazing yellow hair belied the Sephardi origins of her family, prompting the Goncourt brothers (famous writers and minor aristocrats) to comment with characteristic acidity that “when Jewesses are blonde, there is gold at the base of their blondness, like in the painting of Titian’s mistress.”

Louise and her husband had a passion for eighteenth-century French art—something she, at least, may well have inherited; her family home in Trieste (replete with contents) is now a public museum as well. Together they restored a charming château on the outskirts of Paris that had once been the home of Louis XV’s mistress Madame de Pompadour. Their daughter Irène was famously painted as a child by Renoir. She inherited her mother’s long gold tresses and married an older man from Istanbul, whose passion for the French eighteenth century must have felt deeply familiar.

Count Moïse de Camondo’s family were stupendously wealthy Levantine bankers who had recently moved to Paris. Relatives would later blame his “oriental” attitudes toward women for the marriage’s rapid demise. At all events, the Camondos divorced. Irène converted to marry a socialite and a sportsman—dashing, titled, but ultimately the kind of man her parents might have employed to manage their stables. This marriage eventually foundered as well.

As for Moïse, he lived a life of rigid aestheticism. After his mother died, he disposed of everything that seemed to recall the family’s Ottoman origins. Donations flowed from the house to the Musée de Cluny, which already housed the pioneering collection of Jewish ritual objects built up by the composer Isaac Strauss. Most of the family’s treasured collection of Judaica was donated to Synagogue Buffault. Yet we should not quite read this as a rejection of everything his parents had stood for. As Moïse explained in an oddly intimate letter to the synagogue’s curator that recalled the family’s practice of using a particular pair of candelabra to light memorial candles on Yom Kippur, he hoped they would “remain in this destination as long as our descendants will light candles on the occasion of this holiday.”

Free to live on his own terms, Moïse set about transforming his home into a small-scale Versailles. He was creating a stage for the stunning collection of eighteenth-century French furniture, paintings, and objects—all strictly Louis XVI—he would amass over decades. This was not, in his view, a frivolous undertaking but an intensely serious “reconstitution of an artistic residence of the eighteenth century.” It was a house of fragile things, packed to bursting with strictly in-period “paintings, tapestries, statues, bronzes, busts, andirons, chandeliers, sconces, table stools, porcelains, Savonnerie and Oriental carpets, draperies, cabinetry, pendulums, barometers, candelabras and candlesticks, consoles, tables, chairs, window items, boxes of leather goods, engravings, shovels and tweezers.” And it became, in due course, a gift to the nation and a memorial to his only son, Nissim, a French army pilot whose plane was shot down by the Germans in September 1917.

Moïse and Irène’s daughter, Béatrice, married the composer Léon Reinach in 1919. Like the Rothschilds, the Reinachs were German Jews who had made the transition from Frankfurt to Parisian high society within a generation. And like the Rothschilds, the Reinachs were a lightning rod for political antisemitism in France. Indeed, Léon’s great-uncle, Baron Jacques, had committed suicide in 1892 after being implicated in the infamous Panama scandals over the failed financing of the canal—an affair that helped propel the career of Édouard Drumont, author of the notorious antisemitic text La France Juive.

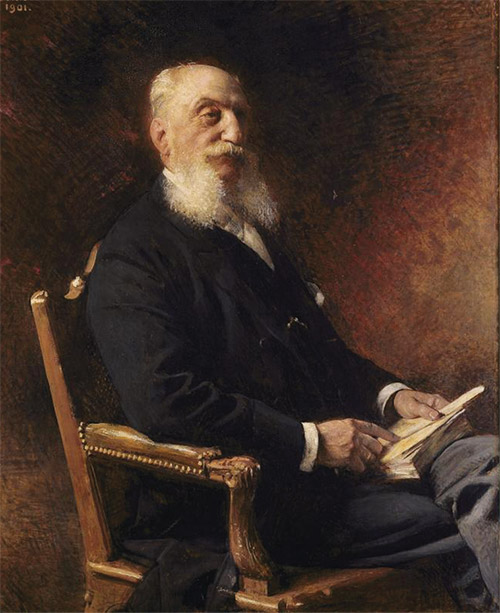

In France, the Reinachs were rapidly and astonishingly successful. Léon’s uncle Joseph was a political protégé of the French minister Léon Gambetta, who became one of the most effective and influential supporters of Dreyfus. Another uncle, Salomon, was a philologist, archaeologist, and historian of religion, keenly engaged with a number of international Jewish causes. As for Léon’s father, Théodore, he was a lawyer, politician, and classically minded polymath who helped establish liberal Judaism in France. Collectively, these three men were known to French society as “les frères Je Sais Tout” (The brothers “I know everything”)—a play on their respective initials and a nod toward their eclectic academic interests and intellectual brilliance.

At the height of the Dreyfus Affair, Théodore built a luxury retreat on the French Riviera. Villa Kérylos—where French president Macron in 2019 hosted President Xi Jinping of China—survives as a monument to the rarefied milieu of its owner. It was, as the secretary of the Institut de France noted with admiration on Théodore’s death, a house whose “details have been borrowed from skilfully chosen archaeological documents, mosaics, bas-reliefs, paintings, vases, lamps.” Like the Musée Nissim de Camondo, it was both a total artwork and a material manifesto for a high-minded French-Jewish symbiosis. It, too, became the property of the nation.

Unlike Moïse’s house, Théodore’s Kérylos did not aspire to authenticity. With its carefully hidden piano and expensive sanitary arrangements, Kérylos adapted the ancient Greek ideal to modern life. A prolific scholar, Théodore wrote 328 articles and books over the course of his lifetime, including a history of the Jews “from the Ruin of Their National Independence Until Our Days” (1884). Published just as the first wave of pogroms in Russia was giving rise to Zionism, it made the case not for nationalism but for a Jewish universalism that Théodore identified with the spirit of modern French republicanism. The Greek villa into which Théodore poured his learning represented a variation on the same theme. McAuley describes the library as “a bibliographic reconstruction of Théodore himself,” although oddly, he fails to mention the Magen David motif that illuminates the mosaics on the library floor.

Across the bay from Kérylos was another extraordinary house. It, too, had been built from scratch, this time by a woman, Béatrice Ephrussi de Rothschild, who had been married off at nineteen to a man almost twice her age, a cousin of Théodore Reinach’s. Her husband, Maurice Ephrussi, was the scion of a Russian Jewish banking dynasty. A gambler, racing enthusiast, and syphilitic bon viveur, he managed to squander quite a bit of his wife’s fortune and render her infertile before they divorced. Béatrice responded by living a life of excess. She collected intemperately and incoherently, traveled exotically, and entertained lavishly. And she left the eclectic Villa Île de France, with its fantastic gardens, to the Institut de France as a monument to her parents—and a museum that would house the fruits of a life spent collecting great art while maintaining “the actual appearance of a living house as much as possible.”

None of this is precisely news to French or Jewish historians. Nor does The House of Fragile Things have much to offer the history of collecting: a specialist field, often preoccupied with provenance, that relies less on letters, memoirs, and architectural plans than painstaking work with old catalogues. What holds this book together, and makes it memorable, is the linkage McAuley forges between memory, material culture, and identity—both Jewish and French.

These links are explored in one of McAuley’s early chapters, which are about the politics of material culture in France and what the historian Tom Stammers has described as “a political debate about who could—and who could not—be entrusted with care of the French past.” It turns out that Édouard Drumont was himself an antiquarian whose first book, Mon Vieux Paris (1878), underlined the importance he attached to the material traces of French history. In La France Juive (1886), he made a similar case, but differently. He presented the Rothschild château at Ferrières—designed by an English architect in a self-consciously pan-European style—in vivid and meticulous detail, as a material manifestation of the duplicity, acquisitiveness, and cultural inauthenticity of the Jew.

Viewed in this light, it is surely right to read the museums men like Moïse de Camondo left to the nation not as simple exercises in patriotism but as an attempt to write Jews and Judaism into the narrative of the nation itself. Nonetheless, McAuley’s book is framed by the French Jewish tragedy in a way that seems reductive given the cosmopolitan origins and orientation of the men and women he studies. Many of these individuals reached out beyond their privileged but suffocating milieu, and some of them left it completely.

Yet perhaps the real problem is less with framing than with teleology, the sense that his subjects were doomed from the start. McAuley wants to work against this, and to celebrate his protagonists for the lives they led and the dreams they nurtured. “The ending has always overshadowed the beginning and the middle,” he asserts in an early allusion to the Holocaust, before saluting his protagonists for their ability to live “according to universalist principles in a time of hateful irrationality.” In practice, however, his book is suffused with foreboding: a to-ing and fro-ing between before and after that constantly reminds the reader not just of what once was but of what would later be.

Their ending gives the protagonists a tragic glamour that the rest of their lives may not have warranted. How would it be, for example, if we focused not on Irène, and her daughter Béatrice, who was murdered in Auschwitz along with her husband and two children, but on her sister Lady Alice Townshend, who was also painted by Renoir? That is a question McAuley himself implicitly poses at the outset, when he describes Lady Alice—with her baptism in the Church of England and seat at the British royal court—as “a rare emblem of what others in her milieu might have become had they, too, managed to live long lives free of the identity categories that had shattered their cosmopolitan world after the rise of Nazism.” Yet it is not a question he considers in any depth.

McAuley’s tragic narratives may be usefully set against the story John Hilary tells in his new book From Refugees to Royalty: The Remarkable Story of the Messel Family of Nymans. Like the Reinachs and the Rothschilds, the Messel dynasty traced its origins to a German Jewish immigrant with a gift for making money. The Messels, too, acquired (or rather built) a grand house, collected great art, and eventually gave what remained to their nation. Unlike their French counterparts, however, the Messels were not murdered in Auschwitz, and they were not forced to flee as penniless refugees like their German relatives either. Instead, they calmly married their way into British society—starting from the bottom and working their way right to the top. Although Hilary’s handling of his Jewish subject matter can be a little off-key, he tells this story well, and his book is a bold (if not entirely successful) attempt to subvert the glossy, deferential genre that is the English country house history.

Ludwig was the first of the English Messels. His parents had been privileged but unemancipated Jews whose families served the grand duke of Hessen-Darmstadt; his brother Alfred was to become an architect whose iconic designs helped define Wilhelmine Berlin—from the once-legendary Wertheim department store to the Pergamon Museum. But Ludwig abandoned Germany for London, perhaps because he thought it was an easier place to be Jewish (as Hilary speculates), but more likely because the capital of the British empire presented financial opportunities of a quite different order. German unification was already underway in 1865, and it did not take so much foresight to realize that states like Hessen-Darmstadt were on their way out.

Back in Germany, the Messels had been well established. Here, they were arrivistes. Ludwig was to become the richest man on the London Stock Exchange, but his wife, Annie, was not even solidly middle class: her father, who had been illegitimate, was a hopeless provider, and her parents struggled to make ends meet. Still, she was English—and Protestant. Their children were baptized, and his son Leonard even became a churchwarden. But Ludwig did not cut ties with his Jewish family. Three of his siblings had followed him to Britain. Rudolph was a successful industrial chemist and a bachelor, Eugenie married a German Jewish stockbroker, and Lina married Isaac Seligman: Ludwig’s boss and a Bavarian Jew who had made a fortune providing uniforms to the Union army during the US Civil War. Isaac was a prominent figure in British Jewish life and a key supporter of Jewish charities at home and abroad (to which Ludwig gave generously as well).

Both Isaac and Ludwig ended up owning grand rural properties in Sussex, an English county conveniently situated between London and the south coast. Shoyswell was a large Elizabethan manor house, which the Seligmans appear to have modernized substantially. Nymans was a Regency villa that Ludwig comprehensively redeveloped, with the help of his brother Alfred, in an unabashedly Germanic style. In 1924, when Lina’s health began to fail, Isaac donated Shoyswell Manor to the Jewish “friendly societies” Achei Brith and Shield of Abraham for use as a convalescent home. Ludwig was already dead by this time, and his daughter-in-law Maud was busily engaged in re-imagining Nymans as a faux-medieval Cotswold manor house—a building that looked authentic but was, in the words of the architect Percy Newton, “the most marvellous fake.”

The point, which Hilary makes nicely, is that the rebuilding of Nymans created a faux-dynastic pedigree for the Messel family, distinct from their identity as German Jewish immigrants. It was a pedigree reinforced by the doors, fireplaces, and ceiling beams Maud sourced from genuine medieval manor houses around Britain—and undermined, only slightly, by a small Magen David relief fitted into the garden wall.

The gardens, ah the gardens. These are now the great pride of Nymans—a much-visited National Trust property—just as they were the great passion of Ludwig (for whom gardening was also a performance of Englishness). Yet the interior of Nymans must have been magnificent, with its extensive collection of old English furniture and Ludwig’s old master paintings. Alas, the Velázquez that hung over the fireplace in the library was one of many treasures to perish in 1947 when most of the extravaganza came down in flames.

By this time, however, the Messels had made it. Leonard and Maud’s son Oliver became one of the foremost British stage designers of the twentieth century. Their daughter Anne married into the British aristocracy. Her son, the photographer Tony Armstrong-Jones, would marry Princess Margaret in Westminster Abbey on May 6, 1960—about the same time that Julien Reinach, then aged 68 and still suffering from the injuries he had sustained in Bergen-Belsen, charged his lawyer with tracking down items missing from his brother Léon’s estate. Featuring prominently in the list of their missing possessions was Renoir’s portrait of la petite Irène.

At first glance, juxtaposing these two dynastic narratives seems to reinforce what we thought we knew about British Jews, French Jews, assimilation, and annihilation. But family histories, like national histories, are constructs. They tell the stories we now want to hear and reflect our pre-existing ideas about the French tragedy or “the British dream.” And yet, following one branch of a family rather than another leads to an entirely different fate.

Suggested Reading

Pew’s Jews: Religion Is (Still) the Key

Who are the “Jews of no religion” in the much-discussed Pew Research Center's “A Portrait of Jewish Americans”? It’s a question that gets at the deep structures of Jewish life and the inadequacy of many of the sociological methods used to describe it.

The Jewish Turn of Norman Podhoretz

A new biography charts the rise of Norman Podhoretz, from a young voice of the anti-Communist left, to a leading neoconservative and American Zionist.

Wishful Republic

What lessons can be learned from the city of Haifa, and what does its culture suggest about the likelihood and limitations of a binational state?

Anita and the Wolf

A new Argentinian film sheds light on living with Down Syndrome.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In