A Heretic in the Truth

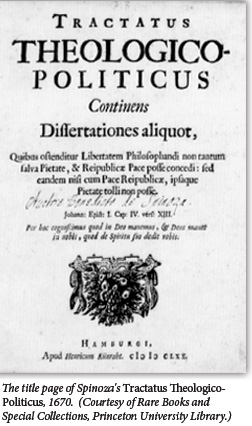

Baruch (Benedictus) Spinoza’s name and legacy have been connected with, or claimed for, a diversity of causes, most notably and insistently that of modern secular liberalism. Spinoza’s reputation was vexed early on. Although he published little in his lifetime, one text, published anonymously in 1670, became instantly notorious in the Dutch Republic and soon throughout Europe. That text was titled the Theological-Political Treatise (Tractatus theologico-politicus). It was a book decried by its immediate readership-theologians, professors, political authorities, even Spinoza’s own friends and correspondents—as “godless,” “full of abominations,” and “forged in hell . . . by the devil himself.” Even Thomas Hobbes, who in his Leviathan had audaciously advocated the subordination of ecclesiastical authority to the power of a secular ruler, is reported to have said of the Treatise, “I durst not write so boldly.”

The “theological” claims of the Treatise are indeed radical. For Spinoza, prophets were men with vivid imaginations; the chosenness of the Jewish people just amounts to the historical fact that the Hebrew commonwealth enjoyed remarkable prosperity before its destruction by the Romans; and miracles, considered as violations of the laws of nature, are strictly impossible. As Spinoza writes early in the Treatise, “whether therefore we say that all things happen according to the laws of nature, or are ordained by the edict and direction of God, we are saying the same thing.” This is all consistent with the Bible, properly, which is to say historically, understood, because it is a work of human literature.

These discussions in the Treatise are then followed by its more overtly “political”—and no less provocative—chapters. Here, Spinoza identifies right with power; argues that the supreme right of governance belongs to a secular, not ecclesiastical, authority; and promotes a tolerant democracy as the best form of government.

Nor can one neatly separate the “theological” from the “political.” Rather, the Treatise weaves together a staggeringly diverse array of subjects—theology, biblical exegesis, political philosophy, metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and more—while announcing its central theme as an argument for the “freedom to philosophize.” This presents a bewildering state of affairs for anyone seeking to provide an adequate account of what Spinoza’s text means as a whole.

Steven Nadler’s new study of the Treatise, A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza’s Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age, succeeds in doing just that. While his tasks are primarily expository and contextual, Nadler, who is the author of the standard biography of Spinoza, puts forward a substantive thesis as well:

To the extent that we are committed to the ideal of a secular society free of ecclesiastic influence and governed by toleration, liberty, and a conception of civic virtue; and insofar as we think of religious piety as consisting in treating other human beings with dignity and respect, and regard the Bible simply as a profound work of human literature with a universal moral message, we are the heirs of Spinoza’s scandalous treatise.

Guided by this set of claims, Nadler takes us through the Treatise in a detailed but seamless account of Spinoza’s arguments and aims. One measure of his integrity, indeed, is that while endorsing the common portrayal of Spinoza as a founder of modern secularism, Nadler is sensitive to some of the ways in which Spinoza is not to be taken as the harbinger of the secular mindset. In fact, A Book Forged in Hell raises the important question of how appropriate it is to view Spinoza as a philosophical founder of contemporary secularism and especially of contemporary liberalism. It also raises the question of whether Spinoza should be understood as a Jewish thinker and, if so, to what extent.

If “secularism” means “politics without God,” then Spinoza’s endorsement of a society free of ecclesiastical influence makes him a secularist. However, while he defends toleration and liberty of conscience as crucial to the existence of the “free state,” he also draws a distinction between “internal” and “external” expressions of belief and maintains that the latter, when it comes to religious matters, must firmly be controlled by the state. It is the sovereign—ideally, for Spinoza, a democratic governing body—and the sovereign alone who is to be the “interpreter” of religion and Scripture, and the regulator of all public religious practice. As the title of the penultimate chapter of the Treatise reads: “authority in sacred matters belongs wholly to the sovereign powers and . . . the external cult of religion must be consistent with the stability of the state if we wish to obey God rightly.”

In fact, nothing in Spinoza’s view prevents the state from censoring the expression of deviant religious views. And while in the final chapter of the Treatise Spinoza argues that it is, as a matter of fact, unwise and even impracticable for the sovereign authorities to coerce people into thinking or saying one thing rather than another, he earlier maintains that, as a matter of principle, citizens should obey all the decrees of the sovereign. Indeed, in the final chapter whose title proclaims, “in a free state everyone is allowed to think what they wish and to say what they think,” Spinoza admits that here “we have moved on from arguing about right, and are now discussing what is beneficial.”

Passages such as this place a good deal of pressure on Nadler’s blanket description of the Treatise as “an extended plea for freedom in the civic realm: freedom of thought and expression, and especially freedom of philosophizing and freedom of religion.” In truth, the matter is not so simple. The subtitle of the Treatise, which Nadler quotes early on in his book, states that “freedom of philosophizing can be allowed in preserving piety and the peace of the Republic; but . . . it is not possible for such freedom to be upheld except when accompanied by the peace of the Republic and piety themselves.” Nadler takes this formulation to show that “the Treatise . . . is an extended argument for freedom of thought and expression in the modern state.” Yet, “peace” and “piety” are, for Spinoza, things over which the state presides. For Spinoza, freedom can (in fact) be allowed only if (in principle) the state-administered status quo is upheld.

This being so, it is far from obvious how Spinoza’s “secularism” ought to be construed. One way to approach the issue is by differentiating Spinoza’s advocacy of a society free of ecclesiastical influence from his attitude toward other political positions closely associated with that core requirement. The chief such position is liberalism: a political ideology intimately linked—both historically and conceptually—to secularism.

Here, Nadler is circumspect:

Is the political philosophy of the Treatise a liberalism? That is a difficult question to answer, in part because of the shifting and uncertain meaning of liberalism itself. More to the point, it is not a helpful question when it comes to Spinoza. His account of the state and of religion is too multifaceted to be pigeonholed . . . What can be said is that Spinoza is, without question, one of history’s most eloquent proponents of a secular, democratic society and the strongest advocate for freedom and toleration in the early modern period.

Where does this leave us? Spinoza’s political philosophy is in many respects inchoate, and the details are insufficiently worked out in the Treatise. Still, the central thought is clear enough to justify Nadler in being less prepared than many to apply to Spinoza the title “liberal,” especially in its modern connotation. Consider, for instance, the following description of the essential liberal standpoint recently offered by the influential political philosopher Jeremy Waldron:

[T]he liberal insists that intelligible justifications in social and political life must be available in principle for everyone, for society is to be understood by the individual mind, not by tradition or sense of community. Its legitimacy and the basis of social obligation must be made out to each individual, for once the mantle of mystery has been lifted, everybody is going to want an answer. If there is some individual to whom a justification cannot be given, then so far as he is concerned the social order had better be replaced by other arrangements, for the status quo has made out no claim to his allegiance.

Waldron’s characterization throws Spinoza’s political values into sharp relief. If we define the essence of liberalism as a concern with the transparent justification of the social world, then Spinoza’s politics is not a transparent politics of liberalism but of prudence. In the Treatise, Spinoza’s anthropology trumps his philosophy. Human beings are buffeted about by volatile passions and governed by the “delirious wanderings of the imagination.” What we seek for human society must be constrained practically rather than theoretically.

Spinoza thus inverts Waldron’s statement of the priorities as between individual and sovereign. For Spinoza, a free state is one whose laws its subjects, acting freely, would wholeheartedly uphold. Yet, concomitantly, a free and rational subject is one “who does by command of the sovereign what is useful for the community and consequently for himself” (my emphasis). Spinoza’s concept of rationality, unlike Waldron’s intelligibility, makes consideration of the individual subordinate to obedience to the sovereign authority—and to the social advantages attendant upon such obedience—rather than vice versa. Surprisingly, if we take the view Waldron describes as paradigmatically liberal, then Spinoza’s theory is, in its most basic assumptions, the opposite of liberal.

Nor is this the end of the matter. True, Spinoza promotes toleration of diversity in belief and rails against ecclesiastical meddling in civic affairs. Yet he also appears to recommend an anti-pluralistic society, in which “piety and religion” are accommodated “to the public interest,” rather than it being in the public interest to accommodate plurality of expression in religious belief. Can a tolerant society be anti-pluralistic? However we may answer that question, the Treatise demands social uniformity and the preservation of the status quo.

In the realm of religion, Spinoza’s views are less elusive than are his views on politics. He comes down hard on all forms of sectarian religion, especially Judaism and Christianity (the essence of which he defines as superstition). Yet even this has not prevented many from asking whether he was not, after all, a religious thinker, and in particular a Jewish thinker.

Although he was famously excommunicated, Spinoza was deeply informed by Jewish textual and intellectual traditions throughout his philosophical career. Descended from a family of Portuguese conversos who had relocated to the more tolerant Dutch Republic of the early 1600s, he studied under many, if not all, of the great rabbis of the Talmud Torah congregation in Amsterdam—including, possibly, the famous Menasseh ben Israel—before his brother’s death required him to take charge of the family business. While quickly disillusioned with mercantile life, and increasingly absorbed by Cartesian philosophy, he continued his Jewish education at the Keter Torah academy run by Saul Levi Mortera, who schooled Spinoza in the tradition of medieval Jewish philosophy.

Although he was no Talmudist, Spinoza’s grasp of Jewish texts and philosophy is manifest on almost every page of the Theological-Political Treatise. Most impressive is his engagement with the thought of Moses Maimonides; at times, indeed, the Treatise appears to carry the ideas of that great medieval thinker to their most extreme conclusion. Such is the case, for example, with Spinoza’s discussion of miracles, in which he takes and runs with Maimonides’ characterization of miracles in his Guide for the Perplexed as divinely implante—but still natural—anomalies in the regular course of things. Spinoza adds a twist: If God is nature, as he famously maintains, and if God’s will and intellect are not distinct (for what grounds exist for distinguishing the two?), then these preordained anomalies or “interventions” amount to nothing other than nature (God) acting according to its own laws. That is, they are themselves natural processes that are neither interventions nor exceptions, even though we may simply not apprehend their causes.

At other times, Spinoza is explicitly critical of Maimonides. In the Guide, Maimonides advocates a method for reading sacred Scripture that will allow the text to be interpreted in conformity with independently established philosophical doctrines. Where Scripture appears to anthropomorphize God, for example, it should be interpreted allegorically so as not to transgress a proper philosophical understanding of God’s (non-human) nature. In the Treatise, Spinoza ridicules this interpretive strategy, asserting that to make philosophers the guides of Scripture “would surely produce a new ecclesiastical authority and a novel species of priest or pontiff, which would more likely be mocked than venerated by the common people.”

Drawing on the work of Warren Zev Harvey, Catherine Chalier, and earlier scholars, Nadler deftly fleshes out the connection between Maimonides and Spinoza in their approaches to prophecy, miracles, and Scripture. Nor was Spinoza’s engagement with Jewish tradition limited to Maimonides. For instance he drew on the biblical commentaries of Abraham ibn Ezra as well as medieval Jewish polemics against Christianity. If deep engagement with Jewish tradition makes a philosopher Jewish, then Spinoza was a Jewish philosopher.

But, of course, Spinoza did not identify himself as a Jewish thinker. As a young man, he was already beginning to depart from the Cartesian and Jewish medieval philosophies and to espouse at least some of the radical conclusions to which he would eventually give full voice in the Treatise and the Ethics. This all came to a head in 1656, when the Talmud Torah congregation of Amsterdam issued its harshest-ever writ of cherem (excommunication) banning Spinoza from the Jewish community in which he had been raised. Although we do not know on what grounds this cherem was declared, the document itself cites (without specifying) Spinoza’s “monstrous opinions.” (Nadler and others have argued that one such opinion was that the soul was not immortal.)

Spinoza appears to have responded by promptly relinquishing any sense of Jewish identity. Jean-Maximilian Lucas, his biographer and friend, reports him as defiantly declaring:

They [the Jewish community of Amsterdam] do not force me to do anything that I would not have done of my own accord if I did not dread scandal; but, since they want it that way, I enter gladly on the path that was opened to me.

In the Treatise, and elsewhere, he always referred to the Jewish people in the third person.

Perhaps the most important criterion for evaluating the Jewishness of a thinker is whether his views are consonant with the pillars of Jewish faith, and here the verdict is clearest. Spinoza’s treatment of Scripture, prophecy, and miracles, together with his views of Jewish chosenness and the purpose of religious practice, emphatically seeks not to uphold but to undermine Judaism. As Nadler correctly points out, “There can be no more serious offense within rabbinic Judaism than denying the continued validity of Jewish law,” which is precisely what Spinoza did.

Granted, alternatives to a complete and practical embrace of Jewish law and custom are now accessible to modern Jews, but, these alternatives, including Reform and Conservative Judaism, did not begin to emerge until the 19th century and were not even on the horizon in Spinoza’s day. For Spinoza, as Nadler forcefully argues, “Judaism” was synonymous with what we would today distinguish as Orthodox Judaism-and it is this Judaism that Spinoza wholeheartedly rejected. Here, one can imagine an objection being raised. Even if Spinoza himself saw no alternative to strict Orthodoxy in Judaism, can the Treatise nevertheless be seen as foregrounding-or as influencing-the advent of non-Orthodox expressions of Judaism or Jewish culture? Nadler is entirely right in his rejection of this approach:

Spinoza had great contempt for traditional sectarian religions and Judaism in particular. And he did argue that Jewish law is no longer binding on contemporary Jews. Perhaps in this sense he unwittingly opened the door for a secular or even Reform Judaism. But he also had a very strict understanding of what was to count as Judaism. Spinoza may have been a religious reformer, but what he envisioned was not reform within Judaism. Rather, what he had in mind was a universal rational religion that eschewed meaningless, superstitious rituals and focused instead on a few simple moral principles, above all, to love one’s neighbor as oneself.

Should Jews, nonetheless, seek to reclaim Spinoza? Jewish intellectuals and politicians from Martin Buber to David Ben-Gurion to contemporary Jewish secularists have attempted to do so. Generally, the effort has involved grossly romanticizing Spinoza’s attitude toward Judaism. But there is another, arguably more credible way in which today’s Jews—some Orthodox Jews included—have appropriated Spinoza, or at least the method he founded. The effort to account for biblical content mainly—if not solely—in terms of its intended meaning and especially through consideration of the historical circumstances that gave rise to the composition and compilation of its various components is central to modern biblical studies. Spinoza’s principles of biblical interpretation probably are consistent with the belief that the texts themselves were divinely inspired, but it should go without saying that this is one of the many Jewish beliefs that Spinoza himself repudiated.

Reflecting at the end of A Book Forged in Hell upon the aftermath of the Treatise, Nadler remarks that Spinoza’s work

did not have the consequences he wanted. Rather than opening up the door to greater liberty to philosophize…Spinoza seems mainly to have succeeded in mobilizing the entire world…against himself.

Nadler’s book ends where it began: the issue of how Spinoza came to be understood. As he shows, Spinoza was regarded as a thinker who so doggedly pursued philosophical truth that he came to embrace the most blatant religious and even political heresies. One is tempted to sum this up by quoting Milton: Spinoza was a “heretic in the truth”—a heretic, that is, for the sake of the truth. Milton, however, meant something else by this phrase, which fits Spinoza even better. In his Areopagitica Milton explained the phrase:

A man may be a heretic in the truth; and if he believe things only because his pastor says so, or the Assembly so determines, without knowing other reason, though his belief be true, yet the very truth he holds becomes his heresy.

Milton retains the pejorative meaning of “heresy” while hurling it back upon the orthodox: The heretic is one who forsakes the truth by not seeking decent reasons for believing it. The Treatise takes such Miltonic sentiment to an even higher pitch, as when Spinoza asks: “[W]hat altar of refuge can a man find for himself when he commits treason against the majesty of reason?” It is difficult to think of a more sobering challenge from a philosopher than that.

Suggested Reading

In Brief, Spring 2012

Baseball, Beats, and Scandals in Satmar.

Dialectical Spirit

A new intellectual biography explores the thought and legacy of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook.

Chopped Herring and the Making of the American Kosher Certification System

In 1986, the discovery of non-kosher vinegar in a classic Jewish delicacy led to a revolution in kosher supervision.

Hanukkah’s Confounding Miracle

How Hanukkah became a holiday of many miracles and none.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In