Bambi’s Jewish Roots

On January 20, 1909, the Bar Kochba Association in Prague launched an ambitious program of “festive evenings.” The organizers hoped for an immediate impact, so they invited Martin Buber, whose cultural Zionism had been generating a great deal of excitement among Central European Jewish intellectuals.

Buber’s emphasis on education and inner self-development, together with his call for the recovery of subterranean Jewish forces and sensibilities, and his promise that this would equip Western Jews to have a key part in a larger, cosmopolitan project of rebirth, all resonated powerfully with Bar Kochba’s leadership. Indeed, in addition to paying tribute to Buber again and again, they kept inviting him back. It was as their guest that Buber delivered the addresses in his celebrated volume Three Speeches on Judaism. And it was enthusiasm like theirs that eventually led Gershom Scholem, who went through his own adolescent infatuation with Buber, to remark on the excesses of “Buberty.”

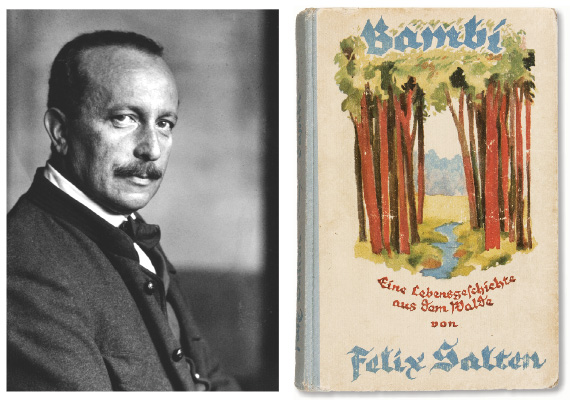

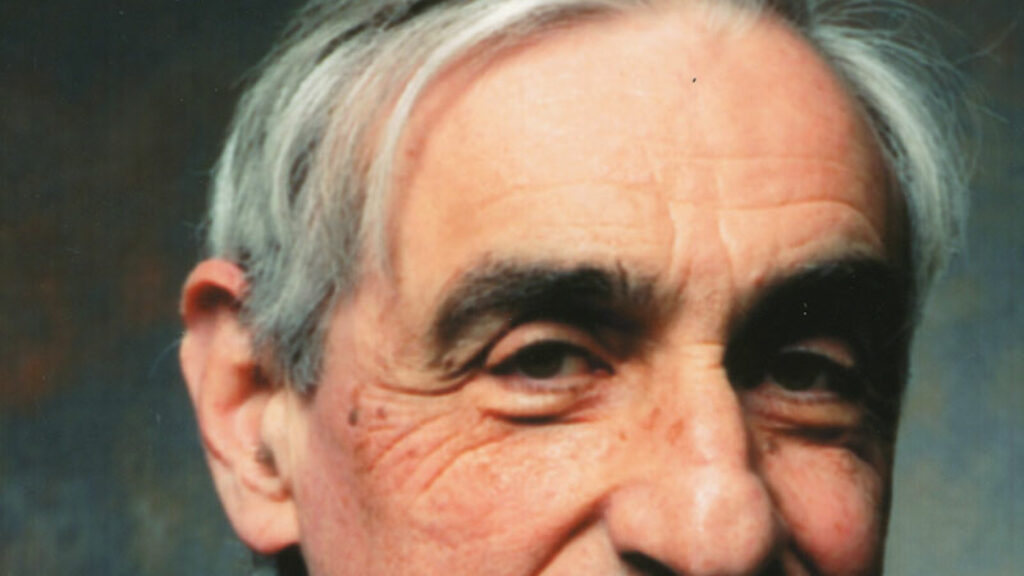

Landing Buber was a coup, but Leo Hermann, the man in charge of setting up the festive evening, hadn’t done as well with his other invitations. Or so it must have seemed. Hermann wanted to pair Buber with someone who would broaden the appeal of the event. His first choice, the novelist Arthur Schnitzler, had turned him down. His second choice, the poet Richard Beer-Hofmann, did too. So Hermann went with Plan C—Felix Salten, who was a friend of both writers. Like Schnitzler and Beer-Hofmann, Salten had been a member of the Young Vienna circle of writers in the 1890s. Unlike them, however, he hadn’t produced any major works, let alone ones that engaged with Jewish themes, as, for example, Schnitzler’s great novel The Road into the Open (Der Weg ins Freie) did. At the time, Salten was mostly known for his wide-ranging activities as a newspaper critic, as a cultivator of connections to the Habsburg family (the great satirist Karl Kraus once described him as a “court journalist”), and for being the author of the pornographic fictional memoir Josefine Mutzenbacher. Published anonymously but immediately attributed to Salten, the book relates, in vivid detail, the story of a prostitute who has “experienced everything a woman can experience in bed, on tables, chairs, and benches,” etc., and who claims to “regret none of it.”

Hermann, of course, turned to Salten for other reasons. At 39, Salten was as fit—he was a devoted hiker and cyclist—and as lively as ever, and he could be a charismatic, even beguiling presence. Rilke, who wasn’t quick to praise, effused over the charm and energy of Salten’s conversation. After attending one of Salten’s lectures, Kafka noted that “the pleasure” of the female auditors had been palpable. Salten was, moreover, intriguing as a Zionist. Of the Young Vienna authors, he alone mobilized his pen in support of Theodor Herzl’s Zionist newspaper The World (Die Welt): During its first year, Salten had a regular column. Inspired by Herzl’s message of self-acceptance (or really, of self-improvement through self-acceptance), Salten became an effective critic of the attempt to hide or disown one’s Jewish heritage. He was also concerned about the menace of anti-Semitism. Salten grew up poor and feeling unprotected, and in his column he addressed the vulnerability of Eastern European Jews living in destitution, as well as the anti-Jewish utterances of demagogues such as Karl Lueger and Georg von Schönerer.

But, above all, it was culture that interested Salten. His most substantial, most searching essay for The World underlines the importance of the theater for Jewry’s self-awareness. His profile of Herzl, composed just after Herzl’s death in 1904, treats the project of political Zionism as the culmination of Herzl’s efforts as a playwright, rather than as a departure from them—as the “fifth act” that Herzl had plotted for the drama of his own life. Having consulted with Buber, Salten brought together his various interests and tendencies as a Zionist commentator in the speech he gave on January 20. The combination proved to be a winning one: Both the Zionists and the non-Zionists in attendance responded with clamorous approval. As the applause for Salten thundered on, Buber, who had worried that following him would be hard, was left wondering how, under such circumstances, he would manage to “connect with the public.” Reviews of the event suggest that Buber’s lecture didn’t, in fact, go over as well. As one participant wrote, “the evening was successful . . . mostly because Salten gave a brilliant performance.”

The years before the First World War mark the highpoint of Salten’s career as a Zionist speaker. He was invited back by Bar Kochba’s leaders, and when, in 1911, he made another appearance in the festive evening series, he shone just as brightly as he had the first time. But even after Zionist lecturing was mostly behind him, Salten continued to write as a Zionist. In 1924, for example, he travelled to Palestine and published a largely admiring book about what he saw there. This was soon after Salten had produced the work that would win him international fame: Bambi.

Bambi first appeared in serialized form in Vienna’s stately paper of record, the Neue Freie Presse. The book version appeared in 1923, and by then the story had established itself as one that appealed to adults and children alike. The American edition was so hotly anticipated that the fledgling Book of the Month Club ordered 50,000 copies before it had even appeared. Translated into English by Whittaker Chambers, of all people, and published in the United States in 1928, the novel was both a critical and commercial success.

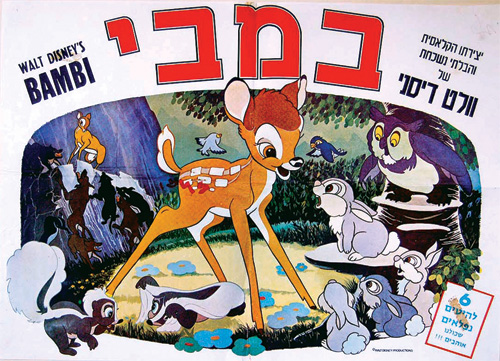

One American reviewer deemed it to be as “profoundly pertinent to the modern experience as The Magic Mountain,” and it impressed more than a few influential readers. Among these was the producer and director Sidney Franklin, who bought the film rights to Bambi in 1933—for $1,000. His plan was to adapt the book to the screen as a live nature film, but he couldn’t figure out how to make it work. Eventually, he sold the rights to Walt Disney, who, with his visceral dislike of hunting, had been genuinely moved by Salten’s novel.

Of course, that didn’t stop Disney from transforming the story Bambi tells. Captiousness, melancholy, and a sentimental streak count among the prominent characteristics of Salten’s animals. The animals in the Disney film, which premiered in 1942, are altogether more frolicsome, brash, and affable. The plucky rabbit Thumper, for example, is Disney’s creation, not Salten’s. In the film, more than in the book, the forest, while no Eden, has an initial tranquility that is shattered by the cruelty of man. Indeed, some viewers regarded the film as registering the trauma of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the loss of America’s innocence. Salten, nevertheless, liked the film, though he always described it as “Disney’s Bambi.” What distressed him were the terms of his contract. In 1941, Salten, whose works had long been banned in Germany, complained, “I have been delivered over to Disney with my hands and feet fettered and a gag in my mouth.” Salten’s heirs would fare no better. In 1996, a senior district judge in California wrote that, “Bambi learned very early in life that the meadow . . . was full of potential dangers everywhere he turned. Unfortunately, Bambi’s creator, Mr. Salten, could not know of the equally dangerous conditions lurking in the world of copyright protection.”

Despite the fact that Salten’s Bambi appeared just before his book about Palestine, critics have hardly ever discussed Bambi in the context of his Zionism. They have spent more energy tracking the affinities between Bambi and Josefine Mutzenbacher (beginning with the mockers who ridiculed the sensual moments in the former book as the work of a “deer sodomite”). Which isn’t to suggest that critics have spent that much energy on Salten. He is a little like Max Brod: principally known now for the people he knew. Because of his role in important literary networks, as well as his enormous output, his name comes up a lot, but even his own literary friends—Schnitzler and Hugo von Hofmannsthal—had their doubts about the seriousness of his efforts.

If the scholarly discussion of Salten’s works were larger, it is likely that we would have detailed interpretations of Salten’s animal stories as allegories of the Jewish experience. For they do lend themselves to such readings, even if Salten didn’t play as much or as artfully as Kafka did with the longstanding associations in German culture between Jews and certain animals (mice, monkeys). Consider The Hound of Florence, another work by Salten that has had an afterlife in American popular culture: It was—and was formally credited as being—the inspiration for Disney’s The Shaggy Dog film franchise. This semi-autobiographical novel tells the story of an artist who must spend every other day in aristocratic society as a dog. A central theme of the novel (and needless to say entirely lost in the Disney films) is the outsider as abject insider.

Much more central in the animal stories, however, is the theme of persecution. It was Karl Kraus who first linked this to Salten’s Jewish background, though not in the way you might expect, especially given that Kraus was writing just after the Nazi Party had achieved mainstream success. Writing about a Bambi spin-off in 1930, Kraus claimed to detect the sound of Jewish dialect—or “jüdeln”—in the speech of Salten’s hares. Salten was a hunter (a humane one, he always insisted), and, as it happened, he had just published a piece about his love of hunting. Kraus joked that Salten’s hares had adopted a Yiddishy tone of voice in order to blend in with a special type of enemy—the Jewish hunter. The hares were “perhaps using mimicry as a defense against persecution.” When Salten died in 1945, an American critic found a more straightforward connection between the plight of some animal characters and that of the Jews. In his obituary for Salten, the critic, having noted Salten’s “Zionist sentiments,” maintained that the fox in Bambi not only comes across as the rapacious “Hitler of the forest,” but also has a mentality of hatred and rage that bears similarities with Goebbels’ anti-Semitism.

It was not until a decade ago, however, that an actual reading of the “Zionist overtones” in Bambi was proposed. In an essay published in 2003, Iris Bruce argues broadly that the novel evokes the “experience of exclusion and discrimination.” But she also pays close attention to its language. Salten’s suggestive phrase for butterflies is “wandering flowers,” and Bambi describes them elsewhere as “beautiful losers” who have to keep moving, “because the best spots have already been taken.” Bruce stresses, as well, that the culture of the deer develops around the fact of their victimization: They tell their children tales that “are always full of horror and misery.”

Likening Bambi to Kafka’s talking-ape story “A Report to an Academy,” Bruce claims that Salten’s work, too, is a critique of assimilation. One of the deer uses the loaded verb verfolgen to ask whether humans and deer might get along: “Will they ever stop persecuting us?” When another deer answers that “reconciliation” with humans will eventually come about, Old Nettla, a third deer with vastly more experience of the world, will have none of it. Indeed, her response foreshadows a line from Salten’s Zionist book Neue Menschen auf alter Erde (loosely translated, new people on ancient ground), which expresses impatience with the enduring “dream of full integration.” Old Nettla seethes that humans, “have given us no peace and have murdered us for as long as we’ve existed.”

Not many of the deer in Bambi persist in believing that living harmoniously among humans is possible. Of the deer that do, two, Bruce points out, wind up being killed by hunters. One of those deer, Bambi’s cousin Gobo, spends time in captivity, and when he returns to the forest boasting of how well he was treated, Bambi is taken aback by how “strange and blind” Gobo has become. Furthermore, where Gobo is proud of the band that humans have placed around his neck (which should have made him off-limits to hunters), the wise “Royal Leader” (fürst) of the deer regards it as a sign of degradation and Gobo as “an unfortunate child.” That Gobo’s faith in humankind leads to his death reinforces the Royal Leader’s assessment. The label “Royal Leader,” on the other hand, reinforces the old deer’s status as a Herzl figure, since at the time Herzl was often given regal titles by Zionist writers. As Bruce puts it, “The old Prince of the Forest, then, can be said to represent Herzl.”

That formulation may be a bit much. As we shall see, Salten’s Zionist background isn’t the only key to understanding what Bambi is really about, as Bruce herself allows. But, in the end, Bruce’s essay provides enough support to make its conclusion seem plausible: “Bambi has Zionist overtones because the critique of assimilation and the longing for a new Herzl figure are prominent themes.” We could, however, cite quite a bit of additional evidence to underpin this claim, especially the part about the critique of assimilation. For example, Bruce might have mentioned the memorable scene when one of the hunters’ dogs chases down the fox, which has been shot. Even the fox’s prey stick up for him, accusing the dog of a self-betrayal that can’t be compared to the fox’s natural cruelty. Also worth noting the scene when The Royal Leader, who turns out to be Bambi’s father, takes Bambi to see a slain poacher. As the two of them stand over the dead body, the Leader encourages Bambi to draw the lesson that he shouldn’t see himself as inferior to his oppressors.

“If you want, it is no fairy tale.” Thus reads the epigraph that introduces Old-New Land (Altneuland), Herzl’s utopian novel of a Jews’ state. Salten might have used the line “it is no fairy tale, despite what you want” at the beginning of Bambi. Like a lot of other early Zionists, Salten wanted to see Jews settle in Palestine, but he couldn’t imagine leaving Europe himself. Part of the reason was the landscape. Salten regarded himself as a true lover of Austria’s forests who was well acquainted with, and could even find beauty in, their darker sides. With Bambi, Salten wanted to disabuse members of the then-popular “back to nature movement” of idealizations that evidently annoyed him. Most nature enthusiasts were, according to him, “familiar only with the lifeless forest, with the forest without animals.” These “friends of nature” were in truth “strangers to nature” and especially to its harshness.

Bambi sets the record straight by emphasizing the inevitability of violence and privation in its sylvan setting. Even without the hunters, the woods would be a dangerous, difficult place for most animals. Their homeland could never be a land of milk and honey. Yet precisely because of the omnipresence of danger in Bambi, the importance of a safe space, a major theme in the Zionist literature of the period, is foregrounded everywhere. Indeed, the Royal Leader never seems more like a metaphor for a Zionist savior than when he leads Bambi to that rarest of things in the forest: a secure mini-territory where Bambi, whom hunters have injured, can at last rest and regenerate properly.

Piling up examples like these has its merits, but it isn’t the only way to understand Bambi. Salten’s Zionism consisted of more than a broad critique of assimilationism and his veneration of Herzl. Salten had other Zionist concerns, too, and taking them into account as we read Bambi helps to make sense of some of the book’s more enigmatic and resonant moments. I am thinking, above all, of Bambi’s encounters with the elk. It turns out that Bambi’s father isn’t the only royalty in the forest. All the male deer enjoy the status of “princes” (prinzen). But the elk, Bambi’s towering “relatives,” are referred to as “kings.” Even more than his father does, these majestic animals intimidate Bambi. Around them he feels not simply small, but also diminished. Confronted with their looming regality, Bambi becomes ashamed of the diffidence and anxiety of his own community. Bambi’s response is to try to think of himself as their equal, and to attempt to connect with them. But he is too awed by the elk to reach either goal. He winds up seeing himself as “nothing” in comparison. And he is unable to bring himself to strike up a conversation with one of them, which further undermines his sense of self and which, from the perspective of the elk, is too bad. As Bambi chides himself, the elk casually wonders why deer and elk speak to each other so rarely. Bambi, for instance, appears to be such a “charming fellow.”

This drawn-out communicative failure has its counterpart—and complement—in Bambi’s experience of the elk’s mating calls, which the novel presents as a kind of aesthetic experience, or rather, as the kind that Salten the cultural Zionist wanted to see. Like Buber and others, Salten thought that Western Jewry had fallen into an unfortunate cycle. Deracination had made real creativity hard to come by, and real creativity in the aesthetic sphere was both a primary end itself and the way to greater self-consciousness and spiritual renewal. Where Buber believed that Western Jews could find crucial knowledge and inspiration in the mystical folk culture of Eastern Jewry, Salten envisioned a progression that would take Jews from the “tear-filled” Zionist dramas of the present to liberating artistic expressions of “Ur-power” rooted in the “consciousness” of the “free person,” and to “mother sounds” as primordial as those “in the books of Job and Solomon.” In the meantime, though, Salten thought that you could find a taste of the elemental in Jewish culture in the “raging” work of Heinrich Eisenbach, an actor whose physical comedy included a popular imitation of ape movements.

Suggestively enough, Salten employed the key terms from his cultural Zionist writings to evoke the sounds with which the elk, those undaunted kings of the forest, call for renewal. As Bambi listens to the “elemental tones” of “a noble, unsettled blood, raging with Ur-power in its longing, anger, and pride,” he is transfixed. Regular conversation with the elk may not work quite yet, but their song affects him profoundly. Bambi can think of nothing else until it stops, and it makes him afraid, in part, perhaps, because of the stirring it induces in the deepest part of his being. Yet as Bambi takes in his relatives’ expressions of Ur-power, he feels something else, too: “pride.” In the end, Bambi may be Austrian schmaltz—this no doubt facilitated its assimilation into American kitsch—but it is a book with complicated roots, which go back to and beyond Bar Kochba’s first festive evening.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

“He Called Me Jim”

In his autobiography, James Atlas explores how and why he spent his professional life living with and overshadowed by complex, overweening literary giants.

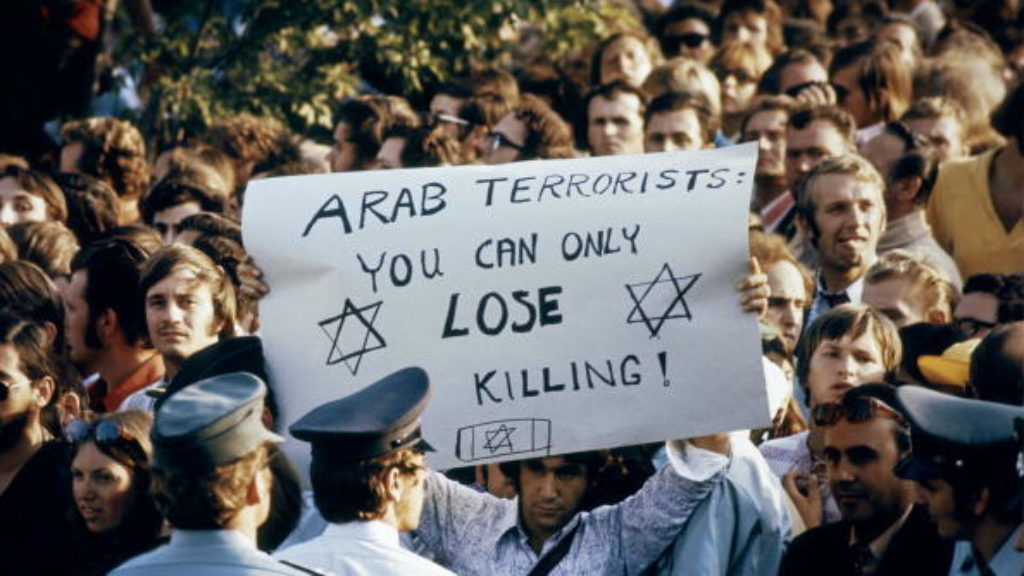

Black September

Organizers of the 1972 Olympic games were determined to avoid recalling Munich's Nazi past—which inadvertently facilitated the bloody massacre of Israeli athletes.

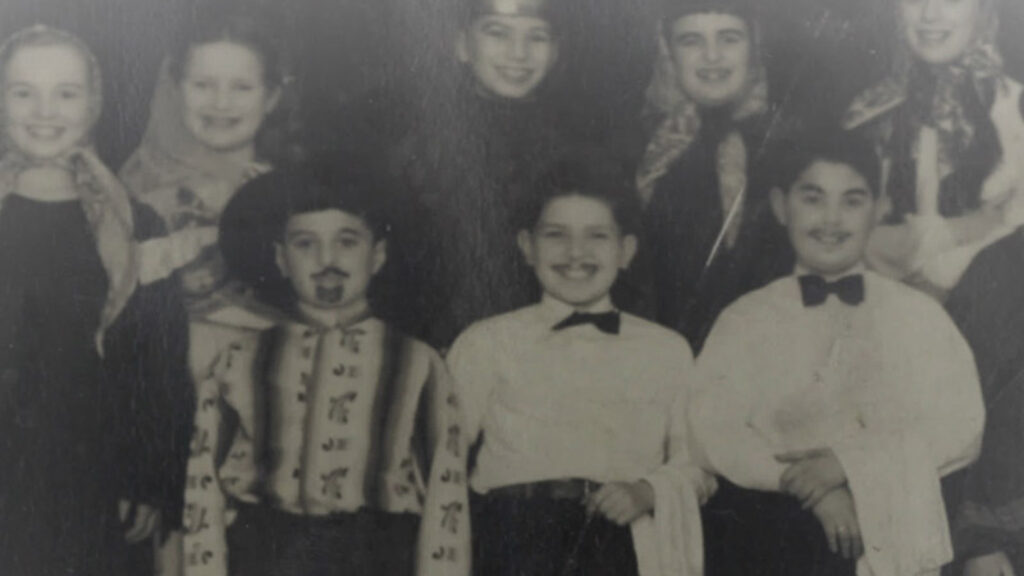

A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

Lyon Cohen wrote and starred in Congregation Shaar HaShomayim's first Purim spiel in 1885--and then led the Montreal Jewish community for half-century. His grandson Leonard didn’t exactly follow his lead, but he does have a big grin in the cast photo of the 1947 Purim Spiel.

Tradition and Invention

If Jews were included in early 20th-century discussions of political communities, it was generally concerning their right to preserve their language and culture, along with other minorities, at a time when empires were being dismantled.

gwhepner

BAMBI AND THE JEWISH QUESTION

Felix Salten’s animals in Felix Salten’s Bambi

show melancholy and a sentimental streak,

In Disney’s movie, which is far more campy,

the animals are far more frolicsome and chic.

For Felix Salten’s readers who are keener

to follow characters that love to frolic

unmelancholically there’s Josefina

Mutzenbacher, a sex workaholic.

In a way that’s very allegorical

his focus is in Bambi on the Jews,

for their impending plight an oracle

stated with a sentimental ooze.

The book has Zionist overtones, the deer

sad victims telling tales of horror to

their children, living in an atmosphere

like Salten’s, where it’s hard to be a Jew,

the butterflies , described as wandering flowers

compelled to move, best spots already taken.

Only with the help of Zionistic powers

could they find new ones, and not feel forsaken.

[email protected]