“He Called Me Jim”

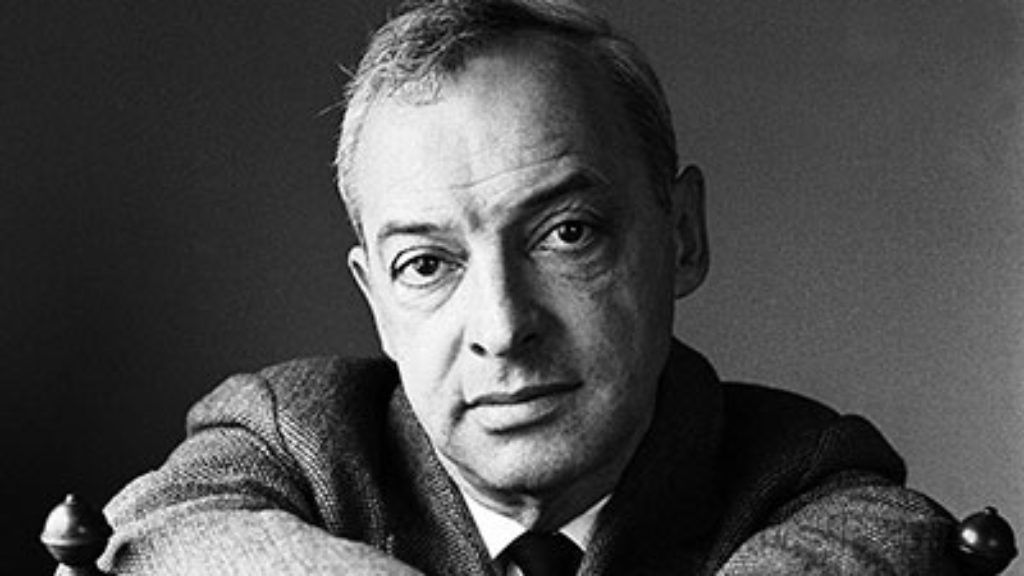

In a particularly self-lacerating moment in The Shadow in the Garden: A Biographer’s Tale, James Atlas describes what it felt like—at least, in his darker hours—to labor on the life of Saul Bellow for nine years:

Most of the time, I didn’t mind our unequal stature and talents: Go, you be the genius. But sometimes I felt: What about my life? Doesn’t it count, too? There comes, inevitably, a moment of rebellion, when the inequality begins to chafe. Biographers are people, too, even if we’re condemned to huddle in the shadow of our subjects’ monumentality.

Atlas’s death of lung disease this past September at the age of 70 felt all the more jarring because he managed to combine a young man’s brashness and raw vulnerability with a literary and historical hunger so sincere, so winning, as to overshadow all else. His memoir is full of recollections of meandering in second-hand bookshops, dead time between projects, a failure as a novelist and poet, and the hectoring that yielded him a job atthe New York Times Magazine. And yet, he produced two illuminating, memorable literary biographies.

Of his attraction to the brilliant, ill-fated poet Delmore Schwartz, whose much-acclaimed biography he completed at the age of 28, he admits:

My connection with Delmore was overt—

so much so that I sometimes wondered if I was writing my autobiography. . . . Delmore’s attachment to the innocence of early childhood, his unrealizable expectations, his piercing loneliness, his book hunger, his literary ambition, his dread of failure, his sense of the sadness of life . . . these were traits and longings we shared.

Atlas’s model for telling his own life was Richard Holmes’s Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, where, in a cluster of beautifully etched chapters, Holmes describes biographical endeavors achieved as well as aborted. In contrast to Holmes, whose personal revelations are oblique, decidedly British, Atlas lays himself bare to his readers. He goes so far as to admit to the discovery, late in life, of a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and of near-disastrous missteps that, time and again, were checked by a wise, level-headed, spouse.

Given his impatience and an aggressiveness that dampened only in his sixties, it was by no means inevitable that Atlas would become a literary biographer. But at Oxford, he became the student of Richard Ellmann, author of a magisterial biography of James Joyce. In Ellmann, he found someone of singular talent who chose to devote his life to writing the lives of others. Not only would Atlas go on to write superb biographies himself, he would launch Penguin Lives, a publishing enterprise of dozens of brief books, many of them extraordinary.

He spent his professional life living with and overshadowed by complex, overweening literary giants. As Atlas himself recognized in his brief and touching Audible book, Remembering Roth, released earlier this year, there was some truth to Philip Roth’s grim, fictionalized portrait of him as a young man in Exit Ghost, published in 2007: “the tactless severity of vital male youth, not a single doubt about his coherence, blind with self-confidence and the virtue of knowing what matters most. The ruthless sense of necessity. The annihilating impulse in the face of an obstacle. . . . Everything is a target; you’re on the attack; and you, and you alone, are right.”

Roth was outraged by the tone and content of Atlas’s biography of Bellow. Roth’s ire may also have been fueled by the fact that he had, at least according to Atlas, been the one to suggest that he write the book. Moreover, Roth was now himself the subject of a biographical endeavor by a handpicked author, Ross Miller, who had once been a close friend. That project had soured and then been dropped.

Atlas acknowledges in his memoir that by the time he nearly finished his 700-page Bellow tome, he found himself unable to sequester not only his dislike for his subject’s tendency to betray wives, lovers, and friends, but his sense that he, too, had been betrayed. What he had expected of Bellow, oddly enough, was for him to become a father figure; that he might play Boswell to Bellow’s Johnson. In The Shadow in the Garden, Atlas quotes the famous passage in which Boswell recalled that “we embraced and parted with tenderness” with still-palpable yearning.

Much of the edginess—and also the indisputable energy—in Atlas’s Bellow is the by-product of just this discomfort. Yet, on my initial reading, I found the book disconcerting. I had first met Atlas while writing my biography of Isaac Rosenfeld, a brilliant writer and childhood friend of Bellow’s who died young and tragically. We developed an easy, amiable relationship that deteriorated when, in the pages of this magazine, in a review of Benjamin Taylor’s 2010 edition of Saul Bellow: Letters I summed up Atlas’s portrait of Bellow as that of “a crabbed man as vain as a movie star, and as promiscuous as an alley cat.” Atlas took offense.

Soon afterward, at the launch for Roth’s final novel, Nemesis, he yelled at me as I stepped off the stage. A few years later, at Roth’s final reading at the 92nd Street Y, I found myself seated in the large hall right next to him. At first, he refused to shake my hand, but then, once we started to talk—at first haltingly, then more and more warmly over the years—we managed to renew a friendship that only deepened. (Atlas’s recollection of that encounter is more rancorous than mine.)

My sense of his Bellow had by then changed, in part because Zachary Leader’s subsequent, minutely detailed, authorized two-volume account largely substantiated Atlas, albeit without his petulance. Leader’s narrative prose is cool and meticulous; there is nothing cool about Atlas’s language. In Bellow, as in nearly everything else he touched, one sees Atlas’s fingerprint smudges, his overheatedness, his tendency to take all-too-quick offense. If, as Richard Holmes has observed, biography is an uneasy mix of fiction and history, few in recent years have proven themselves better suited to expose this uneasiness than Atlas—and to show the bruises. One last glimpse of his rueful self-awareness: He recalls the first phone conversation he had with Bellow to discuss the prospect of writing his life. “He told me to come the next day from one-thirty to three p.m.” And then, Atlas adds—this a glimpse of how he had forever sought to be treated, yet with an awareness of how infrequent such moments were to be—“He called me Jim.”

Suggested Reading

A Little Arabic within Our Hebrew

Tracing lines of a linguistic heritage through Hebrew poetry.

Desire and Power: Adam and Eve in Genesis 1–3

What did Eve really want and what did Adam need?

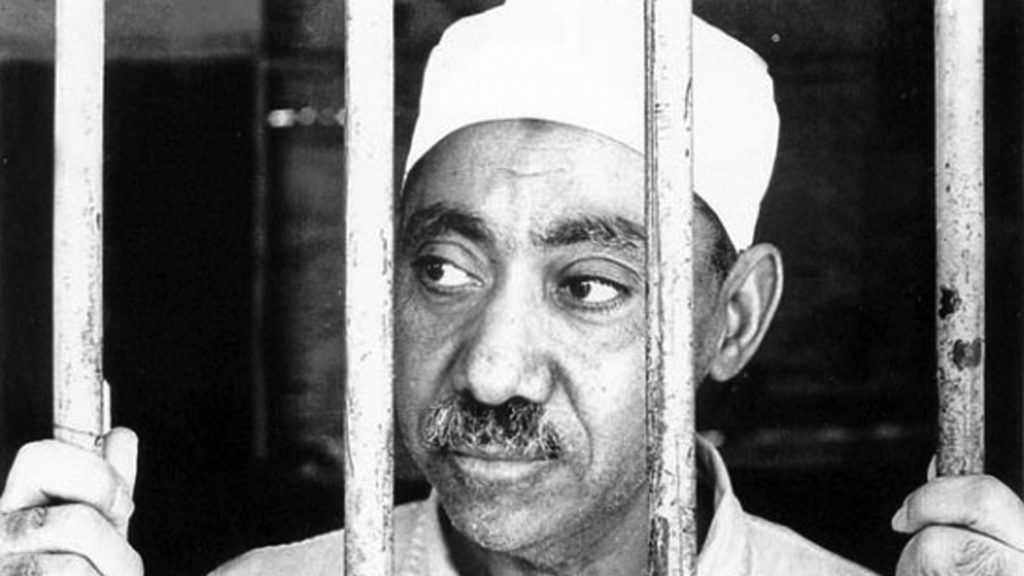

Qutb’s Milestones

A timely look at the intellectual father of radical Islam.

“Love Between Writers”: Saul Bellow and Bette Howland

“I thought you knew that I belonged to the Truth Party too,” Bette Howland wrote her fellow novelist, mentor, and sometime lover, Saul Bellow. Her son recently found a new cache of letters between them that illuminates two brilliant artists at work.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In