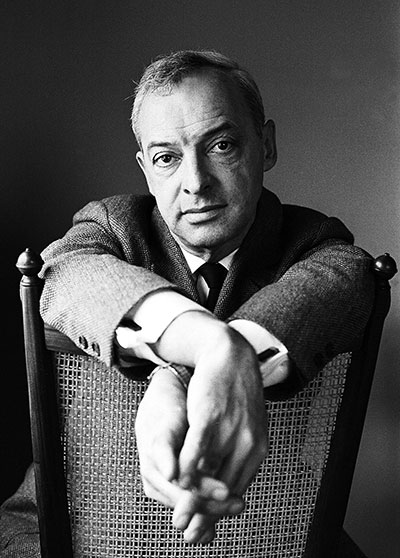

“Love Between Writers”: Saul Bellow and Bette Howland

You and I are able to track each other in words to perfection. I guess that’s what love is between writers. Or perhaps what love is—period.

—Saul Bellow, March 30, 1990

My mother, the writer Bette Howland, kept among her possessions an old postcard with a photo of stained glass from Canterbury Cathedral. The 13th-century “Miracle Glass” shows men carrying shovels and digging into the ground. “WILLIAM OF GLOUCESTER buried beneath a fall of earth, is dug up alive,” the card’s legend explains. William had been excavating an aqueduct when the accident occurred; St. Thomas of Canterbury appeared in a woman’s dream to tell her that he still lived. Bearing a Southampton postmark of July 8, 1968, the card is inscribed as follows:

There are always

some who have

to be dug out

S.B.

At the time she received that postcard, Bette was occupied with her own fruitless digging.

Alone in Saul Bellow’s apartment a few months later—a place, she told him in a letter dated January 21, 1970, that is “[t]o you . . . a sanctuary but to me a mausoleum”—she swallowed an almost lethal dose of pills. According to Bellow’s friend Walter Pozen, quoted in the second volume of Zachary Leader’s indispensable The Life of Saul Bellow, the two “had a long romance, and when they broke up she tried to commit suicide.” (She was not the only woman whose relationship with Bellow set sail in the fair breeze of erotic attraction but foundered in a storm of hurt feelings.) Subsequently confined to a psychiatric wing of Billings Hospital, she nevertheless seems to have taken to heart the advice Bellow offered in his letter of July 24, 1968: “One should cook and eat one’s misery. Chain it like a dog. Harness it like Niagara Falls to generate light and supply voltage for electric chairs.” The fellowship of buried lives she observed on the ward in any case furnished the raw material for her first book, W-3, published by Viking in 1974. Here it is also possible to speak of a miracle, although Bette’s salvation came not from a saint but from a muse. She wrote herself out of the grave.

Bette continued to struggle for Bellow’s attention even after her near suicide. The previously quoted January 21 letter briskly clarifies her disappointment with him:

What I don’t understand is this—you misjudge me if you think it was necessary to tell me that you loved me, because I thought you understood that I belonged to the Truth Party too—I know how to honor it. I know how to respect. I am not only hurt in the way as usual between men and women; but as a colleague, an ally. That is the particular quality of bewilderment and indignation I hope you can distinguish as you file me away. I had hoped to have a real friendship, a life-long friendship.

These words seem to have moved Bellow, for he did not file her away. As Leader wrote to me in 2018, Bette became “an important figure in Bellow’s life. He cared for her deeply and was a great champion of her writing.”

My mother died in late 2017, many years after her books had gone out of print. But two years earlier, Brigid Hughes, the editor of the literary magazine A Public Space, came across W-3 in the $1 bin at Manhattan’s Housing Works Bookstore and included Bette’s work in an issue on forgotten women writers. Prompted by this to look through Bette’s papers, my wife and I discovered a cache of letters and postcards from Bellow that formed the basis of an article I published in Commentary (“Chicago Love Letters: Bellow and Bette,” October 2015). Now, Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, a collection of Bette’s stories that includes those in Blue in Chicago, has appeared as the inaugural volume of A Public Space Books, and plans are in the works to reissue W-3 and Things to Come and Go.

Last year, my brother Frank and I discovered 29 more Bellow letters and postcards tucked away in a cardboard box in the attic, and, inspired by the find, I found most of Bette’s half of the correspondence in the Saul Bellow archive at the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library. Their exchanges reveal a friendship that, while not without unrealistic expectations and occasional recriminations (not least on Bellow’s side), was rooted in mutual admiration and a shared experience of the struggles and pleasures of authorship—a friendship that was, as Bette had hoped, both real and lifelong. One can also hear their inimitable voices. As everyone knows, Bellow was incapable of writing a boring sentence, and so was Bette.

Bellow wrote the earliest letter in the box during his 1973 residence at the aptly named Monk’s House, Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s former home in Sussex, England, where he was trying to finish Humboldt’s Gift. The letter sounds themes that echo throughout the correspondence: the solitude, even loneliness, of literary creation; the sense that writers, being outlandish by nature, do not so much inhabit worldly spaces as haunt them.

Perhaps under your influence, I’ve taken 3 weeks of solitary days and dinners, and nights. It saddens; it clears the head, but if eternity is like this, I quit. When I think of Heaven, I see Heavenly hosts. Even Hell is Italian i.e. basically sociable, in Dante.

I have flowers and birds all day. No people—spooks at night. I appease the last by standing on my head. At night I say to them “You’re no deader than I am.” Or, “I’m as dead as you are anytime.” What I mean by this, I don’t quite know. Perhaps that intimacy for me is the condition of normal existence & this privation is death. And the writing also belongs to intimacy. But this austerity is good for me. That’s it—good, painful & good.

As Bellow indicates, Bette’s routine was one of literary monasticism. “You are to solitude what Linus Pauling is to Vitamin C,” he wrote on January 31, 1980. “You understand I say this sympathetically not satirically. We know too well what it is to be mewed up, bagged cats who never get let out.” “I know your habit when you settle in,” Bellow observed in his letter of April 12, 1979, “something between a homemaker and a holy anchorite. When you set up your bed, your shop, your shelves of books, you tend to lose all sense of time.”

Plato writes in his Ion that “a poet is a light and winged and holy thing, and unable to make poetry until . . . he should be out of his mind.” This is about half right. My mother was winged but not light in soul, and her divine madness, like Bellow’s, consisted in a peculiarly mindful reckoning with demonic human forces. She made cozy nests in isolated locations—an A-frame on an island in Maine, a Quonset hut on the Michigan shore, farms in Pennsylvania and Indiana—filling each with homemade bread, yogurt, beet borscht, and innumerable notebooks and marked-up typescripts until she felt compelled to move on. And what Bellow calls her “shop,” a workspace posted with 3 × 5 cards inscribed with quotations in her beautiful hand (“The way is to the destructive element submit yourself, and with the motions of your hands and feet in the water, make the deep deep sea keep you up. Conrad Lord Jim”), was a scene of quasi-religious devotion to her craft: “Ardor” and “vocation” were two of her favorite words.

Although Bellow regularly complained about Bette’s falling out of touch for long stretches—his short note of August 28, 1978, stated that “I am too parsimonious in the matter of letters to write without knowing where you are,” to which she replied on September 11, 1978, that “It’s OK, a letter to me will not float adrift like a note in a bottle”—he, too, tended to lose track of the days and weeks. “I do it myself,” he admits in the letter that compares Bette to an anchorite, “and it explains why I am such a dilatory correspondent. I never quite see how time is flying and before I’ve known it I’ve defoliated three or four calendars.” But in her letter of September 11, Bette confesses to being lost in space as well as time—at least the metaphysical space in which we strive to locate the substance and human meaning of our lives. “As my grandmother used to say—you told me it was a translation of a Yiddish expression—I don’t know where to put myself. I think it’s the old story—as a writer one really has no life, and really no place to put oneself.” But her instincts on the matter are sound. She goes on to characterize a letter she received from James T. Farrell (whose Studs Lonigan she adored) as “full of affection for one writer to another, a sense of fellowship, which is about what you end up with.” “There is only one place to put ourselves, entrust ourselves,” she concludes, “& that is in & to the affection of friends. I place myself in your affections, my dear old friend, & remind you that you are always in mine.”

“If you don’t succeed [as a writer],” Bette wrote on August 2, 1979, “then you’re nothing. You don’t even have a life; since writers don’t. You don’t even have a—what—a personality, a character.” On some level, Bette always hungered for the black bread of ordinary existence.

Bette did eventually find a place of her own as a writer. She did so in part by triangulation, continuously calculating her intellectual and literary trajectory in relation to Bellow and his landmark distillations and expressions of the vast and vital tradition of American literature. Starting in the early 1960s, the two critiqued each other’s work—sometimes with brutal honesty, at least on her part. My brother recalls Bellow leaving the apartment in anger after she criticized something he’d read to her from the manuscript of Mr. Sammler’s Planet.

No less important, Bellow generously fulfilled his role as mentor. To the extent that he could, he made a place for Bette, promoting her writing and helping her to win major fellowships (a Rockefeller, Guggenheim, NEA, and MacArthur “genius grant”), to attend writers’ colonies whenever she wished, and to land a temporary position at the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, though not a permanent one. These beneficences lifted her to higher altitudes, but there she experienced unanticipated turbulence. Proudly talented, ambitious, passionate, and once spurned, she was naturally both grateful for Bellow’s help and resentful of it.

“I send you a blurb [for Blue in Chicago] which is both objective and passionate,” Bellow joked on December 19, 1977; the blurb stated that “Bette Howland writes of Chicago as only a Chicagoan—one who has paid the price—can write. Her book is passionate but objective—objective but eloquent.” Around this time, he also recommended her for the Guggenheim Fellowship she received the following spring. And when she complained of poor treatment by her publisher and that her friend Joseph Epstein had said nothing to her about Blue, Bellow replied on April 17, 1978, with bracing encouragement.

Yours will be one of those slow-growing reputations and your experience will be like mine. For fifteen years no one paid the slightest attention. Publishers save their money for the winners. And they are plungers. Everything on the favorite’s nose. For some years yet you will be running in the dusty rear. . . . If these resemblances don’t comfort you for Joseph Epstein’s lamentable coolness you’d better reorder your priorities.

Bette’s response of June 26, 1978, acknowledges her substantial debt to Bellow in a way that combines flattery and self-promotion (the letter is in part a piece of salesmanship) with indictment. For in speaking of the suffocating throng that chases after him—one imagines a multitude of grime-streaked women struggling for breath—she turns his horse-racing analogy into an implicit accusation:

I want to tell you, Saul, I do have my priorities straight. . . . There are a lot of us choking in the dusty rear; but I am the one, of all of them, who has had your constant friendship, your encouragement, and your example. And believe me, that doesn’t count for nothing. I know what to make of my advantages—it won’t be lost on me. You didn’t put your money on the wrong horse.

The tone of these remarks is not entirely fair; she was not just a bet (or investment) to be listed in Bellow’s ledger of accounts. That said, he was a trustworthy partner in Bette’s own business, unfailingly honoring her various, sometimes last-minute requests for reference letters. Writing to him in Vermont on August 14, 1979, she asked that he immediately “tell Ms. Sarah de Kay [his assistant] to pull out the standard Bette Howland hand-out letter” and mail it to Millay Colony. He replied on August 29 with chastising good humor:

Ah, what a character you are! A letter from the file in Chicago-and-back-and-out, all by Sept 1? Not with ten Sarah’s on the alert. I did get another, for its purpose, and got it in to the mails, in time, I trust, and much amused—bedeviled amusement. Which of us is Krazy Kat and which is Officer Pup? You may remember Ignatz the mouse zinging bricks with deadly aim at the Pup’s head while Krazy, adoring, clapped hands and gazed into the heavens.

Bette could make like Ignatz when she wanted to. She needed—demanded—a relationship with Bellow, but always (at least after the crisis of 1968) on her own terms. But Bellow needed her attention and approval, too, and occasionally zinged a few bricks of his own to get them.

In late 1981, Bette twice asked Bellow to send The Dean’s December. When the book appeared to unusually critical reviews, she wrote on January 30, 1982, to offer support.

As far as the book goes, I think you should stand up, face the music—in short, stick out your tongue. Publishing a book is no crime (even though it makes me feel I’ve done something wrong & I don’t know what). Have read a couple of reviews of Dean’s December (& have already cancelled a magazine subscription because of one); I read them for the quotes from you—things you say about your craft—messages to those who have ears to hear. This always refreshes & reassures me that all is well.

Bette nevertheless let most of the year pass without offering any substantive opinion of Bellow’s new book. In a letter of October 10, 1982, she asks if he’d be willing to read the manuscript of her new book (published the following year under the title Things to Come and Go). She wonders whether he received the copy she’d mailed of her story “The Life You Gave Me,” and in a postscript, she mentions that my brother Frank was “falling out of his seat reading ‘The Dean.’”

Bellow’s response, dated October 28, 1982, and typed in evident haste, reproaches her for ignoring him, for being “spacey” and inhabiting an “imaginary sphere” outside of time, and especially for her own lamentable coolness regarding his book. The letter is worth quoting in full.

Dear Bette,

I never like to say no to you. After all you are one of my protégés, the oddest of them all in fact, and the office of protector, you will not deny, I have filled rather well. In my time I was a protégé myself, and I know how bitter the role can be. But let’s get away from the abstract words and deal briefly in facts. There are protégés and protégés; and protégés annd [sic] protégés. I take a recent instance: I went to some trouble to get you into the Ragdale Residence (or whatever they call it). You were in the suburbs for several months and I was in the city. You phoned in once to say that you were around and that I would hear from you. That you were around is certain because I met the Mrs. from the Foundation (what’s her name?), and she told me that you were hard at work. Why didn’t you let me treat you to a hamburger downtown, or to a pizza at the Medici? And why do you send me Frank’s comment on The Dean’s December, but pointedly refrain from saying anything at all? It gives you an air of fiddling with the peg that holds back the blade of the guillotine. I am not at all worried about my neck, which is heavily armoured, but I think that if you can maneuver yourself into the position of a disinterested party, you may begin to see your behavior as I do—spacey. I did read your piece in Commentary, and of course I liked it, but I saw no reason in the world why I should tell you so. Besides, you were well aware that I would like it and you were only asking for a maraschino cherry.

But perhaps it is only your singular sense of time. When it comes to time you make Proust look like a stick-in-the-mud. You are in some kind of imaginary sphere in which you and I suffer no changes and you appear to be perfectly sure that when we next meet, (a decade from now) we will be exactly as we once were. We won’t, I assure you.

Well to hell with all these proud idiosyncracies [sic] of yours. If you send your G. D. manuscript I will read it. Don’t call it either The Life You Gave Me or Things to Come and Go. Rotten titles, both of them.

Yours earnestly,

Saul

Like Bette’s “Truth Party” letter, Bellow’s rebuke seems to have hit its mark. In an undated holiday card written sometime after November 1982 (he mentions a story published that month in the Atlantic, which can only be “Him with His Foot in His Mouth”) his mood is expansive and astronomical, as at the end of The Dean’s December: “I wanted to say, though, how pleased I am that you wrote to me. Right from the center of the Bette galaxy where all the sweetest intelligence is, and the best judgment.” He nevertheless returns to the old plaintive leitmotif of the letters, shrouded here in a haze of self-deprecation. “What I conveyed to you in a cloud was a dim thought about the defective time sense of people who write fiction. Maybe they have a confused conviction that their friends will be there, dusty but faithful like the Little Toy Soldier on the mantlepiece.”

Over the next few years, Bellow became intimately acquainted with time’s brutal march. He wrote on June 30, 1983, to acknowledge Bette’s greetings on his sixty-eighth birthday. “We are near and dear friends, and I was pleased, excited, touched by your note—Incredible! that I should have reached such an age. I never reckoned on it. Thank God, I am not quantitative in outlook. It would have made heavy counting.” But as his marriage to the astronomer Alexandra Tulcea began to unravel, pleasure and excitement gave way to a sense of cosmic isolation. He wrote on July 11, 1984, to say that, “It would do me good to hear from you. These are intriguing difficult days. I feel like a most complex telescope situated in the arctic circle. I can see celestial fires but it’s a comfortless environment, the immediate one. Won’t you write me a nice human letter?” By November 29, Bellow’s mood had not improved. Shedding his “garment of self deception,” he admits to being depressed:

What I suffer from isn’t a clinical depression, it’s a life-summary-uneasiness of considerable magnitude and comes with a full inventory of mistakes I can’t expect now to correct. . . . There’s also sickness, madness, senility, death. My brother Sam is in Sloan-Kettering having a tumor removed from his intestines. Only too probable that it’s a metastasis.

As Leader writes in his biography, the following year was Bellow’s nadir. “My brother S is in decline,” he informed Bette in his letter of March 16, 1985. “My brother M has just had cancer surgery again. My first wife, Anita, died last Sunday. The Angel of death is recalling our model. When he laps me I think it likely that I will be found at my Smith Corona.” Three months later, on June 25, he delivered even worse news.

Within two weeks—late May and early June—both my brothers died, both fully aware that death was coming. Morris said, “It’s curtains”, and Sam, “Get these hysterical women out of here so I can do it quietly.”

I came to Vermont last week, and here I am trying to

re-assemble myself. My existence? It feels more like being. The numbers on the

chronometer read 70, and perhaps reassembly (with ingenious substitutes for

missing parts) is not a firm possibility. I am not actually sick but I am

beaten low. One can and does prepare for one’s own death; out of egotism, you

neglect to do it for the others.

I loved them both, loved all of them.

Bette replied with heartfelt condolences on June 30. She also informed him that she was rereading his books, starting with Humboldt’s Gift, and “I have finally figured it out.”

From composers, we expect almost as a matter of course that their work will develop over time; & from artists, too—some enrichment and maturing. We don’t expect as much from writers, especially in America. . . . What I have figured out is that you are one of the rare ones. The pace of your production has quickened, your prose has too (though that one wouldn’t have thought possible). That is the nature of your gift; that, moreover, is what it’s about.

Which is just to say—I’m really looking forward.

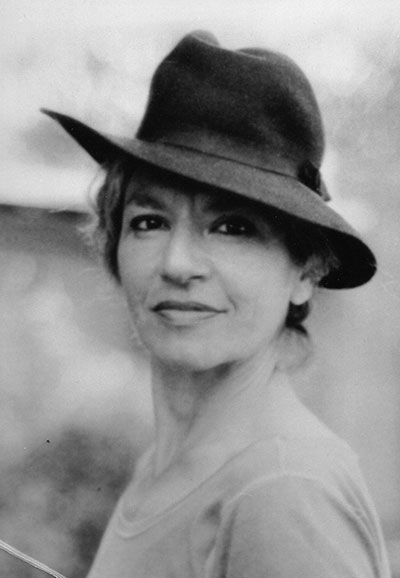

This letter seems to have cheered him, and a photo she sent didn’t hurt, either. “As for the picture, it is beautiful,” he wrote on September 12, 1985. “It would have knocked a Titian or a Delacroix to the ground. When he got up, he would set out to find you. B. Howland en plein essor, in full feather, eyes, brows, mouth and hat, bearing a clear winner. Chalk up one victory over Life, that dirty fighter. I take great pride in you.”

Letters to Bette Howland by Saul Bellow. Copyright © 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985 by Saul Bellow, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

Bette Howland’s letters are quoted courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago Library.

Suggested Reading

Father Abraham

Jews, Muslims, and Christians all revere Abraham. But is it the same Abraham?

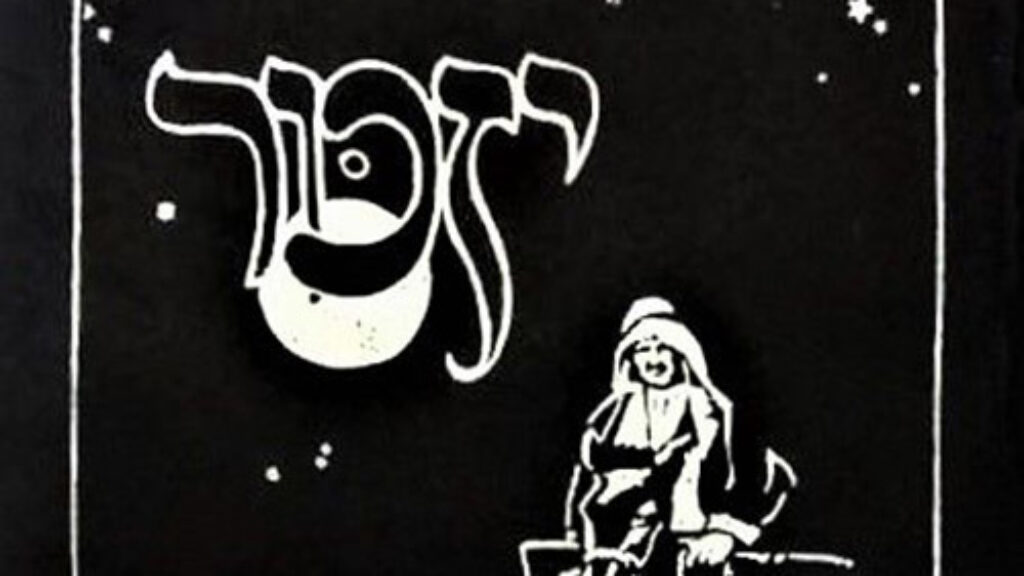

Let the People of Israel Remember

The earliest literary commemoration of Zionism’s fallen heroes was a book entitled Yizkor, published in Palestine in 1911 by members of Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion).

Free Radicals

The history of American anarchists, and of Jewish anarchists in particular, has been forgotten, largely overshadowed by the history of the American communist movement.

Lost from the Start: Kafka on Spinoza Street

Jerusalem-based writer Benjamin Balint has crafted a wise and eloquent study of Kafka around the eight-year battle in Israeli courts over Max Brod’s literary estate.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In