Anita and the Wolf

In the late 1980s, I used to walk from my apartment in Morningside Heights to Shabbat services for “beginners,” at Lincoln Square Synagogue. One Shabbat, a friend prevailed on me to come back to hear Rabbi Saul Berman give his afternoon talk. The main sanctuary was filled not only with congregants from the morning services, but with dozens of teenagers with Down Syndrome. Berman spoke—I remember the soft earnestness of his voice—about the patriarchs, slowing his delivery to consider Isaac. He described Isaac’s imitative tendencies, his apparent naiveté, and his simple trust. Then Berman offered—to the collective gasp of at least part of his audience—a suggestion: “Isaac had Down Syndrome.”

I have sometimes tried to recount Berman’s talk, especially after my son with Down Syndrome was born. But I rarely do these days, usually discouraged by the looks of offended shock or condescending incredulity it almost inevitably elicits. I understand the resistance to Berman’s take (though the history of rabbinic interpretation is full of daring leaps), but while sitting in shul among those boys—adolescent, gawky, and attentive—Berman’s words resonated with me as, for lack of a better word, true.

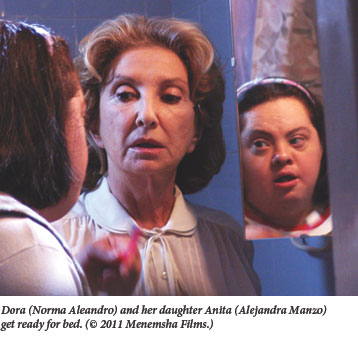

Marcos Carnavale’s Anita, the Argentinian film featured in the 2010 San Francisco Jewish Film Festival and now in distribution in the United States is set against the backdrop of the 1994 bombing of the Jewish Community Center in Buenos Aires. It begins with a mother rousing her daughter in Yiddish “Mein feigele, good morning.” Anita, her mother’s little bird, awakes exclaiming “There’s a wolf!” before she is reassured that wolves are not in the city park, but only in “forests and mountains.” Anita (movingly played by Alejandra Manzo) is a young adult with Down Syndrome. Her widowed mother, Dora, still lovingly manages every aspect of her life, presiding over, among other things, “hot cocoa and vanilla biscuits” at the window table of her favorite coffee shop.

A morning comes when Dora instructs Anita to remain alone in the family stationery store. Dora assures her anxious daughter that she will be gone only the short amount of time it takes to collect their disability subsidy from the Jewish Community Center nearby. While Anita is alone in the store, climbing a ladder to arrange merchandise on one of the shelves above (though her mother had warned her against it), the bomb explodes, shattering windows and throwing her to the ground. Anita is left, alone and unprotected, to wander the streets of Buenos Aires.

A morning comes when Dora instructs Anita to remain alone in the family stationery store. Dora assures her anxious daughter that she will be gone only the short amount of time it takes to collect their disability subsidy from the Jewish Community Center nearby. While Anita is alone in the store, climbing a ladder to arrange merchandise on one of the shelves above (though her mother had warned her against it), the bomb explodes, shattering windows and throwing her to the ground. Anita is left, alone and unprotected, to wander the streets of Buenos Aires.

In the days that follow, Anita, lost and hungry, meets those on the margins of Argentinian society: immigrants and outcasts, vagabonds and thieves. In the first of these encounters, Anita, her nose still bleeding from the blast, meets Felix. She is waiting by a payphone as he argues with his estranged wife. Smashing the phone in frustration, Felix turns to Anita apologetically: “You can’t call anyone from this telephone anymore.” After Anita extends her hand to him—she always wants to make human contact—he reluctantly takes her back to his apartment.

To Felix’s persistent inquiries, “Where do you live?” Anita, who does not know her own address or her last name, much less her phone number, can only answer: “with my mommy.” Felix, who does not make the connection to the bombing, persists: “What happened to you?” to which Anita responds, “I fell off the ladder.” “You fell down the ladder,” Felix laments, “and my life fell into pieces.” Anita is abandoned on the streets of Buenos Aires, but the people she meets are almost as vulnerable.

Anita may be marketed in the United States as a heartwarming, even feel-good movie—and Manzo’s expressive face of trusting frailty will bring most viewers to tears at one point or another—but it is also a careful meditation on the nature of helplessness, trust, and love. Anita—in the face of repeated rejection—remains unabashed in expressing her desire for love. Before falling asleep in Felix’s strange house, Anita asks her unenthused and temporary guardian: “Sing to me.” Although one night he painstakingly combs her hair, he never does sing to her and eventually cannot help but abandon her, stealthily ditching her on a bus. Later, he asks a bartender, “What do you do with someone like this?”

Later, another outsider, an Asian shopkeeper, herself without a husband, at odds with her adolescent son, pushes Anita out of her grocery store twice before taking her into her home. Again abandoned, hungry, and feverish, Anita is rescued by homeless scavengers who discover her searching through piles of garbage and, only after much debate, bring her to the home of a relative, a nurse, Nori, who succeeds in tending her back to health.

In the relationship between Nori and Anita, Anita moves beyond the sense that the film’s protagonist is just someone requiring care. One night, Nori, seemingly disoriented, trips and falls, calling to Anita to take her to the examination room in her house. Anita dutifully follows her directions, swabbing the wound with disinfectant. Nori’s cries of pain seem in excess of the cut on her lips, though the film never explains her anguish. Anita first blows on the wound, as Nori’s weeping gives into cries of sorrow: “They are all sons of bitches.” Anita caresses her face—”I didn’t know that”—hugs her, kissing first her cheek, then her forehead.

Throughout Anita’s odyssey, her older brother has been searching for her. Eventually he meets Felix, who can only remember that her name began with ‘M’. This is not a promising lead until he realizes that this broken alcoholic is trying to remember the words mein feigele.

I do not remember whether Rabbi Berman mentioned that kabbalists connect the patriarch Isaac with the trait of gevura (strength or courage). Anita, for all her helplessness, emerges as the most heroically self-possessed character in Carnevale’s film, a little bird who needs care, but is also able to sing and give comfort. Helplessness, as the British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips parses Freud, “is the most important thing about us.” The beginning of ethics in Anita is not only caring for the other, but acknowledging helplessness—even one’s own—as a virtue.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Halakha and Theocracy: A Response

Allan Arkush fails to see the novelty of the theocratic idea in Judaism.

Darkness and Light: Leonard Cohen and the New Cantors—A Playlist for the High Holidays

Old World Ashkenazi cantorial art—khazones—is making a comeback, with a surprising little boost from Leonard Cohen's new single (yes, that Leonard Cohen).

As American as Augie March

Once again, Maya Arad marries the metafictional play of Nabokov with the moral warmth of Jane Austen.

Available Light: Pictures from Yemen

Yihye Haybi, a Jewish medical assistant to an Italian doctor in Sana'a, found himself in possession of a camera. Self-taught and working under difficult circumstances, he captured the waning days of Yemen's ancient Jewish community.

nathan.kravetz

I admired the film very much, as did Mr. Kolbrener. Anita is first rather passive but eventually she shows initiative. She shows that someone like Anita is teachable, affectionate, and thoughtful. Let's enjoy this moving film.