Available Light: Pictures from Yemen

In 1929, while sailing home from a trip to Italy and Eritrea to visit relatives, 18-year-old Yihye Haybi met an Italian doctor who was also on his way to Yemen. Born to a modest soap merchant family, Haybi had, for a few years, attended the modern school founded by arch-Maimonidean rationalist Rabbi Yihyah Qafih. Impressed with the bits of Italian Haybi had picked up in his travels, the doctor hired him to work as an interpreter and house manager at the medical clinic he was establishing in Haybi’s hometown of Sana’a.

Bright and capable, Haybi quickly worked his way up to medical assistant, giving injections and procuring supplies from Italy. Soon the Jewish community was summoning him during medical emergencies, and he began seeing “patients” after morning Shacharit prayers, before reporting for work. Beloved by the clinic’s staff, he was given various forbidden Western gadgets including a record player, a radio, and, fatefully, two automatic cameras.

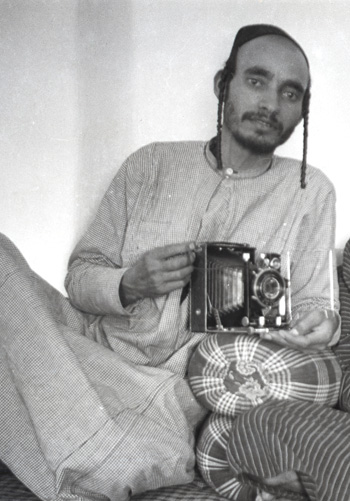

Once he had mastered the techniques of the darkroom, Haybi began to photograph landscapes and events, but it was portraits that he favored and at which he excelled. His oeuvre even includes a few self-portraits, thanks to the delayed time-release feature of his cameras. A trusted liaison between the European, Muslim, and Jewish communities, Haybi was able to gain access to the highest ranks of nobility in the royal Muslim houses, his Italian employers and their families at their leisure, and the great rabbinic families and sages of the day.

Haybi’s photographs, the subject of a recent exhibit at The Israel Museum’s Ticho House in downtown Jerusalem, are trenchantly discussed and elegantly displayed in the accompanying book introduced and edited by curator Ester Muchawsky-Schnapper. The photos on display, spanning the years from 1930 to 1944, are an ethnographic treasure documenting the waning years of an ancient community. And, though beautiful and compelling in their own right, when viewed in light of the challenging circumstances in which he worked they also reveal a remarkable figure behind the lens.

In 1918, with the end of Ottoman rule, a medieval Shia Zaydi dynasty was reinstated in Yemen with Yahya ibn Muhammad Hamid ed-Din serving as both imam and king. Western influences were viewed with suspicion, and the Jews’ inferior dhimmi status was restored. Most daunting of all to a budding cameraman, photography was illegal, deemed both an act of espionage and a violation of Muslim religious practice. Only one other indigenous Jewish photographer, David Arusi, is known to have taken pictures of the community in Yemen in the early 20th century, and only a handful of those photos survive. All other extant photographs were taken by Europeans, who shot, as it were, through an Occidental lens. In that regard the Haybi collection, wide-ranging in subject matter and following the inquisitive gaze of one of its own, offers a fresh and authentic look at this unique Mizrachi Jewish community in its waning moments. Numbering some 55,000 in Haybi’s day, today it is estimated at no more than 200.

Forced to circumvent the government ban, Haybi still managed to cover a great deal of ground. In one photograph furtively shot from a window we glimpse the procession of the Yemenite king on its way to prayers. The procession is caught as it passes through the Jewish quarter, with its mandatory low, unadorned walls contrasting with the high, ornate buildings of the Muslim neighborhood documented in other photos. It is this documentary impulse, coupled with an intuitive and idiosyncratic eye, that mark Haybi as a gifted and important photographer.

In 1922, four years after the Zaydi dynasty known for its long legacy of anti-Jewish edicts resumed the throne, the government of Yemen reintroduced the medieval Islamic law requiring Jewish orphans under age 12 to be forcibly converted to Islam (gezeirat ha-yitomim). Haybi captures one such unfortunate child, earlocks shorn, surrounded by his Muslim guards. (Ironically, the traditional Jewish practice of wearing earlocks, or pe’ot, was forced upon Jewish men as an act of humiliation, because they were regarded as effeminate.)

In another, Jewish men are seen engaged in the demeaning task of disposing of animal carcasses outside the city walls. Vultures crowd the foreground of the picture frame, flapping their wings and kicking up the dust, adding to the sense of filth and abasement. In a kind of topographical palimpsest that may have been a tribute to the community’s tragic past, Haybi even photographed the dry Al-Sayileh riverbed where Sana’a’s Jews lived until their expulsion in 1679. Upon their return a year later they were confined to a swampy area of the city where they constructed the Jewish ghetto.

In other photos, though, the proud traditions of the community are on display. His “Interior of the Al-Kissar Synagogue” showcases the ornate, silver filigreed Torah case. Barred from decorating building exteriors, the considerable artistry of Yemenite Jewry was devoted to ritual objects. Shooting indoors using available light at a slow shutter speed, Haybi reveals his gifts as a cameraman working under difficult conditions and with limited technical means. Focus falls away centrifugally from the foreground and center given the narrow depth of field, but the Torah, at the precise center of the picture frame, can be seen in all its glorious detail.

With no photographic tradition to refer to, Haybi instinctively grasped how best to position his subjects. The great sage and healer, Rabbi Yihye Ghiyath, is posed against a dark curtain wrapped in the light-colored Western-style tallit introduced to Yemen in the early 20th century, an open Talmud resting on a stave of rough wood before him. The spare and simple props effectively guide the viewer’s eye to the rabbi’s face and hands. It is a beautiful and stark representation of the man, conveying at a glance his intelligence, gentleness, and authority.

A portrait of the Italian doctors and engineers playing cards is composed as casually as the game they’re enjoying, but to artful effect. Grouped loosely around a table, one is wearing what appear to be lounge pajamas, another has a cigarette dangling from his lips, and the third slouches, gazing at the camera out of the corner of his eye. Only the armed and turbaned Yemenite guard at their feet sits upright facing the camera, gazing intently, a swarthy, formal contrast to the white-shirted, light-skinned, blasé Europeans.

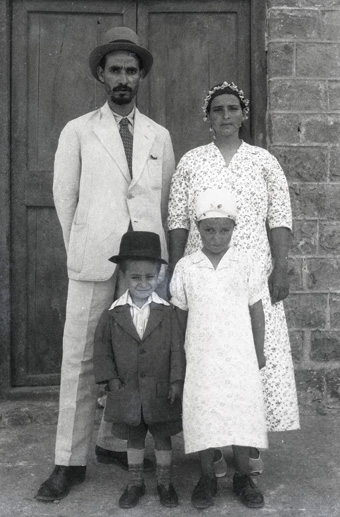

As his reputation grew, local Jews started enlisting Haybi for family portraits, eager to send pictures to their relatives in Palestine, to which a trickle of Jews had been immigrating since the late 19th century. The wealthy extended Arussi family is formally posed in their upper courtyard, a space typical to Jewish homes and a favorite setting of Haybi’s because the exterior light was ample and it was free from prying eyes. The elaborate and exotic hair-covering of the girls and women, the males posing in their tallitot, and the amulet-laden children with painted faces to ward off the evil eye remind us that this was a deeply superstitious and traditional society.

Nonetheless, it’s shocking to see a wedding picture featuring a newly married 10-year-old bride, though child brides were not uncommon. Shot inside an elegant home, soft sunlight bathing the background, Haybi achieves a remarkable range of focus despite the limited light. The gazes of the groom and other guests are eager and curious as they stare into the unfamiliar apparatus. Not so, the frightened and bewildered look of the little bride. Haybi shot a fair number of Sana’a’s weddings, though never the ceremony itself, which would have been considered an invitation to the evil eye. We see Haybi posing his already-married sister in her ornamental bridal dress in a picture that has become somewhat iconic, given Sana’a’s renown for its distinctive and highly elaborate bridal wear. Another more spontaneous picture of a giggling bride with her friends in an inner courtyard captures a wonderfully carefree and rare moment since marriage was considered a very solemn affair—particularly for the bride.

The authorities turned a blind eye to Haybi’s Jewish and European portraits, but opportunity and daring drove him to recruit members of the Muslim upper classes to sit for him as well. Sent frequently by his Italian employers to the homes of the royals and nobles whom they treated, his photographic instincts proved equally canny with these subjects. He poses two child princes in highly ornate dress side by side in a garden, every detail of their sumptuous brocade outfits in crisp focus down to the Arabic calligraphy on their caps and the ornamented daggers in their belts, as befitted their rank.

Drawn to secular public occasions as well, Haybi was careful to shoot those events surreptitiously so the authorities would remain ignorant of his activities. He would have achieved a photojournalistic coup when he captured the moment a saber descended to behead a convicted criminal at a public execution. But shot on the sly, the grainy photo locates the central event in the lower right-hand corner while most of the picture frame is filled with spectators. Nevertheless, Haybi can be playful even when taking extraordinary chances. He can’t resist snapping a picture of the king’s court jester, for example, plunked down irreverently on his master’s throne, surrounded by his cronies.

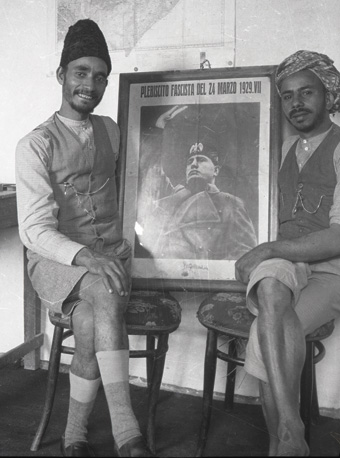

Given the span of history covered by the exhibit, it is unsettling to see only one photograph that indirectly conjures up the shadow of events in the Jewish communities of Europe at this time, half a world away. Suggesting the insularity of the Yemenite Jewish community, it depicts a smiling Haybi, earlocks tucked, and the Muslim cook at the clinic holding up a framed poster of Mussolini—a favorite of their Italian employers.

In 1943 Yemen’s Jewish community finally was able to procure an official photography permit for Haybi. Ester Muchawsky-Schnapper speculates that his work was already beginning to be threatened by the authorities and an official permit seemed prudent. But only a year later anti-Jewish outbreaks had increased in frequency and intensity, and Haybi fled Yemen, making aliyah with his family.

In Palestine Haybi’s fate was typical of the multitudes of Yemenite Jews who followed him a few years later in Operation Magic Carpet, a rescue effort following pogroms in Yemen that brought virtually the entire remaining Yemenite Jewish community to the newly established state of Israel. After a few months in a tent camp, he was given temporary agricultural work before finding permanent employment in a laundry in Ra’anana. A photograph of the Haybi family in Western clothes taken a few years after they immigrated to Israel shows the radical cultural change they have undergone. The air of self-assurance so dominant in self-portraits Haybi snapped in Yemen only a decade earlier is gone; he appears shrunken and diffident.

Yihye Haybi continued to take pictures in Israel, but he was no longer the sole community photographer at the crossroads of overlapping cultures. Hoping to publish his trove of pictures once he became a pensioner, he died of a heart attack only a month after his retirement, at the age of 66. His widow, Rumiyeh, eventually succeeded in publishing his life’s work from which the priceless photographs of this exhibit and book were drawn. We owe her a debt of gratitude.

Suggested Reading

Forget Remembering

Rutu Modan’s graphic novel The Property explores the uneasy coexistence of love and death.

Kibitzing in God’s Country

It may come as a surprise that there is an entirely different Catskills, a Catskills that doesn't involve Grossinger's, bungalow colonies, or Jews, in the words of Billy Crystal, eating "like Vikings."

Something Antigonus Said

When the Saducees misinterpreted Antigonus of Sokho, they lost eternity--at least that's what the Rabbis thought.

Miami Vices

As it is, The Orchard reads more like Days of Our Lives than Daniel Deronda.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In