At Professor Bachlam’s

The anti-hero of S.Y. Agnon’s posthumous novel Shira, Dr. Manfred Herbst, is a professor at The Hebrew University in Jerusalem in the 1930s. Born and educated in Germany, like so many of the actual faculty members at the institution in those days, Herbst tends his flock of index cards, tirelessly searching for the final footnote to complete his work on Byzantine tomb inscriptions, the one that will, he hopes, earn him tenure. Agnon, ever the witty Galician, skewers the dry, pedantic, Germanic personality of his leading man, whose very name, Herbst (German for autumn), telegraphs that his best days have fallen like so many dry leaves, while he is weighed down by domestic life, departmental bickering, and writer’s block. And Herbst is by no means the only target on which the novelist sets his sights. Agnon, who lived in Jerusalem throughout the period during which the book is set and traveled a great deal in its academic circles, peopled Shira with many semi-ridiculous professors who bore suspicious resemblance to his neighbors.

Although Shira was not published in its entirety until 1971, some chapters began appearing already in the late 1940s, immediately sparking attempts to unlock the presumed roman à clef, just as in the case of the recent Israeli film Footnote (He’arat Shulayim, reviewed in the Fall 2011 issue of this magazine), which explicitly drew on many elements of Shira. Many have argued that Agnon’s pompous Professor Bachlam was based on Professor Joseph Klausner (1874–1958), a Lithuania-born Hebrew University professor, chief editor of The Hebrew Encyclopedia, and losing candidate in the first election for president of Israel. Agnon and Klausner were neighbors in Jerusalem’s Talpiot suburb and had a famously chilly relationship, as documented by Klausner’s great-nephew Amos Oz in his memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness.

The main plot of Shira revolves around Herbst’s brief extramarital affair with the eponymous nurse Shira, whom he meets in a hospital while his wife is delivering their third child. His obsession with the rather unlikeable and unfeminine nurse further derails him from his work, but she disappears in the middle of the novel, leaving “Mr. Adjunct Professor Dr. Herbst” in the lurch. What happened to her? “I won’t show you Shira, whose tracks have not been uncovered, whose whereabouts remain unknown,” the narrator concludes the novel. But the author, whose work is replete with indeterminate endings, also left an alternate conclusion to the unfinished manuscript in his files. His daughter and literary executor, Emuna Yaron, published it posthumously: Shira had contracted leprosy (there are clues to this earlier in the novel) and was secluded in Jerusalem’s leper colony, where Herbst ultimately finds her, condemning himself to the same diseased fate as the price for his obsession.

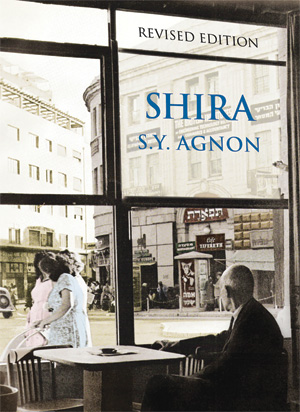

The main plot of Shira is tragic; the accompanying academic satire is tragicomic. The chapter before us is the epitome of that satire—so much so that the note Agnon left on the manuscript pages indicated that he thought it might need softening to be included in the final work. In fact, while it clearly belongs in the novel’s Book II, between chapters 5 and 6, it was only included by Yaron as an appendix to the second posthumous edition of 1974. When the novel was first translated to English in 1989 by Zeva Shapiro, it was left out. We present it here for the first time in English, as an excerpt from the newly revised edition of Shira, which has just been published as the first volume of The Toby Press’ S.Y. Agnon Library.

The visit with Professor Bachlam went well. He opened the door with a cold greeting, nor was he particularly cordial toward Mrs. Herbst. And quite right that he should offer a cold greeting, for Herbst had never praised a single one of Bachlam’s books—and he’d authored over sixty books, and each and every one deserved sixtyfold measures of praise. And besides, Herbst was unliked by him, like all the other academics who were unliked by Bachlam. Some were unliked for one reason, and others for some other reason, but of all these reasons the bottom line was the unspoken praise they should have showered on him instead of remaining silent.

He began discussing the day’s news as broadcast on the radio, and criticized the lead story in Ha’aretz, which was written in ink, not blood, like all the other articles, which don’t contain even the tiniest drop of blood. After that he mentioned the lecture of a visiting professor, who had acquired quite a reputation in the scholarly world, despite never having innovated a thing. If one were to find something noteworthy in any of his books it would be that he hadn’t mentioned that this had already been mentioned by Professor Bachlam in this or that book. Having mentioned his own books, Bachlam began listing them one by one, and their various editions in multiple translations, some having been translated into the same language by two different publishers. Even though the world’s greatest professors have already declared that Professor Bachlam’s insights are unparalleled among those of other scholars, here the world spins on with nary a mention, save for two or three lines about his newest book. But he pays no attention to such things, for these things don’t interest him, and he has no spare time to dwell on such matters, for he is busy with his next great, seven-hundred page book, to say nothing of the footnotes and indices which will take up many printer’s galleys. He does all this on his own, with his own hands, despite his many illnesses and pains and anguishes—quite literally every bone in his body aches. But he overcomes his pains, just as he overcomes his adversaries, through his unnaturally great spiritual strength. Having mentioned his adversaries he began to disparage them. They work in Jewish studies, yet are ashamed to be known as Jews. So-and-so calls himself Ludwig, while another calls himself Wolfgang, this one Walter and that one Kilian. Oh, you scoundrels, shouldn’t your first patriotic duty be to go by Hebrew names? It’s the least you can do in the name of the Jewish people! Mrs. Bachlam had a very nice non-Jewish name, yet exchanged it for a Hebrew one. I say to you, madam and sir, isn’t the nice Jewish name Hannah more suited for a Jewish woman than the name Janette, which Mrs. Bachlam had at the start?

Mrs. Bachlam rose and brought tea and cakes, and was praised for her homemade cakes—both the large and the small ones. In general, said Mrs. Bachlam, I enjoy doing things by myself. By myself I bake, by myself I cook, by myself I look after the house, and by myself I take care of the garden. The professor always asks, Hannah, how can you do so much all by yourself, with just ten fingers? And I answer him: Issacher, how can you write so many books with just ten fingers? And not just that—you also give so many lectures, and write essays, and travel to Tel Aviv to lecture at Ohel Shem, and at dinners for the Jewish National Fund, and conferences of Brit Rishonim, and at gatherings of the Veteran Zionists and at so many other conferences and committees, and he answers me, You’re right Hanitshki, you’re right, but since I’m so busy I have no time to think about how I manage to do so much. But I worry that I won’t be able to complete my magnum opus which I’ve been toiling at day and night for over twenty years. I tell him: Issacher, you’ll finish it, you’ll finish it, and he smiles his charming smile at me and says, Without you, Hanitshki, what would I do in these times which are so strange to me? I tell him, Issacher, don’t be foolish. You say the world is strange to you, but the whole world is pressing to get near to you, and nothing happens in this world without you. Mrs. Herbst, there’s no day that ten messengers aren’t coming to see him—ten did I say? Really it’s twenty or thirty. They come from the Jewish National Fund and the United Israel Appeal, and from the General Zionist Party and the Veteran Zionists and from Brit Rishonim, and from the Nationalist Student Union, and they all come and beg him to speak. He smiles, my professor, his good smile and says, Hanitshki, perhaps you’re right. I shout and tell him, Issacher, you say “perhaps,” and I say if I’m not right there is no right in the world! Since she mentioned “right in the world” Professor Bachlam begins discussing worldwide righteousness, as described by our Righteous Prophets and by the Greek philosophers, and on the phrase “flourishing of righteousness” as mentioned in the Prophets, a phrase we find in cuneiform inscriptions especially in the context of the Assyrian Kings, without diminishing the original Israelite meaning, for such is the way of intellectual trends, that nations and languages are impacted and nourished one from the next. There are turns of phrase in Bialik’s poetry which everyone thinks are original, that he coined them, when in fact they appear in the poems of Pushkin. My dear Mrs. Herbst doesn’t know Russian, so I will translate for her and she’ll hear. Tchernichovsky is unique, he’s completely original. We Jews can’t fully appreciate this giant, who thanks to me has become a Hebrew poet, but originally wrote in Russian, lyrical poems in Russian, but through my influence began writing in Hebrew. Madam, you should take Tchernichovsky’s poetry and read it day and night. Day and night! A poet like this in any other nation would be raised on high. Ah, but we are a downtrodden folk, with no need of poets—we need money. Money and more money! The national funds want money, more money! And what do we get in return? I asked Ussishkin this; what did he say? Nothing. He had nothing to say. I don’t deny the value of money. Certainly the world needs money. I myself pay membership to forty different societies, and don’t even remember their names. Even though I am a rememberer, that is, I have a phenomenal memory. I coined this word—“rememberer”—myself. One of my four hundred linguistic innovations. In two weeks I will mark the forty-seventh anniversary of my first publication, which revolutionized our world—and many of my linguistic inventions have entered our vocabulary, even though no one asks, who coined this phrase, or who came up with that word. So it is with all living things—they go about living without asking or wondering who birthed them. Madam, every day you use this … or that … new Hebrew word—did you ever consider who created them? If I were to count up all the words I coined I could write a book of twenty printer’s galleys-length—and that’s just the words, aside from the footnotes which would take another thirty galleys. Twenty galleys plus thirty galleys—that’s fifty printer’s galleys. Tell, me, madam, how many professors from our university have produced books of that length? And that’s nothing compared to the books I’ve already published. Please, if madam will follow me for a moment I will show her something which will amaze her for the rest of her days. Does she see these binders? Seventy-one volumes, each containing an article I myself wrote. And if madam will just raise her head a bit to look up at the top shelf, she’ll see the stack of newspapers my articles appeared in. When I gaze at the bounty of articles that have flowed from my pen I am amazed—how did I manage to write it all?

Mrs. Herbst rose from her chair while Professor Bachlam led her by the arm to the book shelf. While they stood there Bachlam said, Please, madam, stretch your arms out wide to each side. You see the books in that arm-span? I wrote them all, and still there are some that don’t fit between your arms. I doubt that even our friend Adjunct Professor Herbst could encompass all the books I’ve written between his outstretched arms. I’ve invested my whole life—and that of my wife—and haven’t gained a drop of benefit in this world from all these books, while to them—pardon me Adjunct Professor Herbst that I include you with the German crowd—to them authoring one small footnote the size of a lizard tail qualifies a man as a scholar. I am not speaking of the Gentile scholars, who write, and print, and publish great fat books. Why just yesterday I received a book from Professor Meier—six hundred folio pages—folio pages, madam, not mere single-sided pages. If we count pages it comes to one-thousand-two-hundred, aside from the footnotes and references and bibliography which take another hundred pages. And you wouldn’t believe your ears about what the book is about—it’s about . . . [Agnon had left these facts—the particular newly coined Hebrew words, and topic of Meier’s 1,200 page book—blank in the MS., apparently planning on filling them in at a later point.] Hanitschki, is that the doorbell? Where’s the maid? Go see who it is. Sit, madam, sit, you needn’t go. The guests who have arrived are just neighbors. Allow me to introduce you, Mrs. and Mr. Kattakibo, this is Mrs. Herbst and Mr. Adjunct Professor Dr. Herbst.

Since the neighbors weren’t intellectual folks the professor changed topics to news of the day, goings on in the country, and public affairs. He scratched the end of his nose, and rubbed his hands together, and said, From a reliable source, but of course I cannot say who, I’ve heard the Allies already have plans in place for what to do with Germany after the war.

Mrs. Bachlam looked adoringly at her all-knowing husband, from whom nothing escapes, yet she grew bored by the political talk. Turning to Mrs. Herbst, who was known as an industrious housewife, she asked about her apricot preserves and what she does with grapes, if she makes puddings, and why hadn’t she brought her small daughter along. Professor Bachlam loves small children like life itself. Having overheard something about children, Bachlam jumped up and said, Madam, madam, grownups are worthless, but the children are our hope—only through them will we build our nation . . . Mrs. Bachlam chimed in detailing the professor’s great love for children. He eyed her with resentment for having interrupted him, plotting to regain control of the conversation as soon as she let up, and when she paused to inhale a breath, he began speaking, but she again broke into his words. So unfolded their dialogue of praise, his-for-her and hers-for-him, until other guests arrived—neighbors, academics, and students. Bachlam greeted them, gave them refreshments, and had an interesting word for each and every one suited to his interest, until the day grew dark.

Professor Bachlam was a religious man. While he had sharp criticism for various Jewish practices, and wrote critically of various superstitious customs, he was strict about most mitzvot and never violated the Sabbath. Therefore he didn’t put the light on in the room, but hinted to his wife that she might turn it on. When the light was lit the Herbsts got up to leave, but the professor detained them, first in the room, then in the hallway, and finally in the foyer. In the end he escorted them out, asking them to return soon for another visit. Outside there remained a bit of daylight, with cars carrying Sabbath travelers filling the street. Mrs. Herbst wanted to walk back to town on foot, but along the way felt very weary and wished to take a taxi, which Herbst agreed to do, since while talking with Professor Bachlam he thought of various things he wanted to fix in his article, and feared the long walk by foot would cause him to forget.

Sitting in the car Mrs. Herbst remarked to her husband, This man we were visiting has no love in his heart, not for a single person in this world. Herbst replied, But he has great love for the greatest man in Israel. Mrs. Herbst asked, Who is the greatest man in Israel that Professor Bachlam loves? Herbst answered, He is the one! Professor Bachlam himself is the great man in all his glory. In any case, it’s good that we made the visit. Perhaps on account of it he won’t stand in my way, or at least he’ll soften his objection to me. Mrs. Herbst sighed and said, If only!

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Israel’s Arab Sholem Aleichem

Sayed Kashua's new novel presents a characteristic depiction of the dual identities of Israel's Arabs.

Strange Journey: A Response to Shmuel Trigano

Two historians challenge Shmuel Trigano’s analysis of anti-Semitic violence in France.

A Failure of Reimagination?

We once worried about the faith of young American Jews; now we worry about their politics. It’s part of a long historical development we should resist because Judaism-as-politics isn’t enough.

Pogrom: A Poem

Will the hunters come again to our abode tonight, seeking our souls with gun threats? Will they come quiet and furtive, until the crack of a shot cuts through the crickets? Perhaps they will arrive with a shofar blast like the lords of the land subduing the world, bringing their sons to teach them the wiles of war, carrying our…

lawrence.kaplan

I wonder whether Oz's description of Klausner in his memoir was influenced by Agnon's portrait of Bachlam.