Between New York and Jerusalem

“[Scholem] is so preoccupied that he has no eyes (and not only that: no ears). Basically, he believes: The midpoint of the world is Israel; the midpoint of Israel is Jerusalem; the midpoint of Jerusalem is the university and the midpoint of the university is Scholem. And the worst of it is that he really believes the world has a central point.”

—Hannah Arendt to Kurt Blumenfeld, January 9, 1957

“I knew Hannah Arendt when she was a socialist or half-communist and I knew her when she was a Zionist. I am astounded by her ability to pronounce upon movements in which she was once so deeply engaged, in terms of a distance measured in light years and from such sovereign heights.”

—Gershom Scholem to Hans Paeschke, March 24, 1968

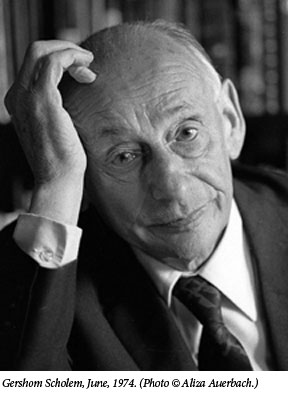

Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem, two of the most gifted, influential, and opinionated Jewish intellectuals of the 20th century, maintained an extraordinary correspondence from 1939 until 1964. Many readers will be aware of the gladiatorial exchange between these two giants during the early 1960s occasioned by Arendt’s (in)famous Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. As a result, Scholem and Arendt have been typically regarded as intellectual foes, formidable ideological enemies. Those who only know of their later animosity will be considerably surprised by Scholem’s enthusiastic 1941 description of Arendt (to his New York friend, Shalom Spiegel) as “a wonderful woman and an extraordinary Zionist.” Now that their full correspondence has finally been published, in an edition meticulously assembled, annotated, and explicated by Marie Luise Knott, we can begin to understand the contours and dynamics of a relationship that was always complex. These letters illuminate the historical record by placing into context and documenting not only the profound differences between these powerful personalities but also their commonalities, shared activities, interests, and loyalties. (One hopes that English and Hebrew translations of this correspondence are forthcoming.)

Although for most of their correspondence, Arendt was in New York and Scholem was in Jerusalem, they most frequently wrote to each other in German (here Scholem is Gerhard not Gershom). They did so, moreover, as quintessential German-Jewish thinkers. Throughout their lives, both Arendt and Scholem remained deeply grounded in the restless intellectual culture of the Weimar Republic. They both formulated a radical critique of German-Jewish bourgeois “assimilationism”; both advocated, and were active in, the politics of collective Jewish affirmation; and they were both acutely aware of the breakdown of tradition, and of the need to grasp the past—and orient the present and future—in radical new ways.

The two had met fleetingly in the early or mid-1930s, but their real dialogue began in Paris in the autumn of 1938. Scholem was returning from New York, where he had delivered the lectures that would eventually be published as Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, and stopped in Paris to meet his great friend, the philosopher-critic Walter Benjamin. Arendt, whom Scholem described to Benjamin as having been “Heidegger’s prize student,” was there preparing Jewish refugee children for life in Palestine. The first letter in this volume, from Arendt to Scholem, is dated the following Spring, on May 29, 1939.

This is a correspondence that spanned a quarter of a century, yet Scholem and Arendt’s actual meetings were few and far between. In fact, there is no known photograph of them together—the book features a picture of Arendt on the front cover and Scholem on the back—and many of their letters concern planned but never realized meetings. On September 22, 1945, Arendt noted: “It’s five minutes after the end of the war and we still have not been able to arrange a meeting at the corner café.” This was a reference to their frequent wistful, and eventually self-ironizing, comments upon a never-to-take-place 5 o’ clock post-war reunion at the Café Westen (an allusion to Jaroslav Hašek’s comic novel The Good Soldier Schwejk).

Given their divergent viewpoints and flammable egos, it is not surprising that on the few occasions when they found themselves together, they did so with a certain anxiety. Just before a meeting in Zurich in July 1952, Arendt wrote to Scholem: “I’m happy about us seeing each other again. Don’t be argumentative. Let’s have a few nice days; we both know we can do it.” As it happens, Scholem subsequently wrote to Arendt how much he had enjoyed it.

The letters also contain innumerable expressions of reciprocal admiration and evidence of mutual assistance. “If possible, please send me all your materials; they interest me very much,” Scholem wrote Arendt in July 1944. In March 1945, he requested that she send what he had missed in her work so that he could have a full “archive” of her writings. Included in Scholem’s collection was the manuscript of Arendt’s early biographical study of Rahel Varnhagen, the German-Jewish salon hostess and early Romantic. Scholem regarded it as a vital piece of scholarship, which depicted the deluded misapprehensions of post-enlightenment German Jewry. In fact, it was Scholem, who, in the chaos of wartime, proved to have been the one to save the last copy of the manuscript, enabling Arendt to finally publish the book in 1956, more than two decades after she had composed it.

For her part, in New York, Arendt acted as an advocate for Scholem. She struggled mightily, and not always successfully, to get Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism reviewed, and eventually published her own glowing piece, which he described to another correspondent as “one of the two intelligent criticisms I have seen of my book.” She also sent Scholem and his wife Fania frequent food parcels during the difficult years of rationing in the Yishuv.

Although Arendt would publish in her Origins of Totalitarianism one of the most influential accounts of National Socialism and anti-Semitism, their wartime correspondence contains surprisingly few theoretical discussions of the crisis through which they were living. But mutual, deeply painful, personal concerns generated by that catastrophe abound. In a letter dated October 21, 1940, Arendt delivered the shattering news of their friend Walter Benjamin’s death by suicide in Catalonia while trying to escape the Nazis. “Jews are dying in Europe,” she wrote, “and one buries them like dogs.” Scholem, as his wife Fania reported to Arendt, was devastated. He later replied to Arendt: “Oh, we have so much to talk about and who knows when we will again have the opportunity. We have, so to speak, to eat our way through this mountain of darkness.” A little later, in February 1942, he wrote that one had to go on writing, “without which we cannot fulfill our duty toward the dead.” (He dedicated Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism to Benjamin.)

For all that drew the two thinkers together, their ultimate interests and goals diverged. Arendt may have been fascinated by the Jews—her analyses of the psychological machinations entailed in secular Jewish creativity and her (probably self-reflective) critique of the assimilation process remain exemplary. Judaism itself, however, hardly interested her and though early on she advocated Jewish collective political action, she grew increasingly skeptical of the Zionist project. She was trained and remained within the worldly philo-Hellenic European tradition (her philosophical diary is frighteningly full of erudite Greek quotations). Her great project was to rethink “the political”—the necessity of pluralism and the very possibility of politics—in a post-nationalist, post-totalitarian age.

These commitments affected her ideas on Jewry. Prior to and during the war, Arendt’s intellectual and practical Jewish and Zionist commitments had seemed clear. Her study of Rahel Varnhagen was compatible with a Zionist critique of assimilation. She worked with Youth Aliyah, and insisted that “politically I will always speak only in the name of the Jews.” Yet, even then, Arendt qualified the above statement by adding that this only applied when “circumstances force me to give my nationality.” When, immediately after the war, her friend and teacher Karl Jaspers asked whether she was a German or a Jew she replied: “To be perfectly honest, it doesn’t matter to me in the least on the personal and individual level.” In an April 1951 entry in her philosophical diary, she provocatively declared that the Jewish idea of chosenness was both unpolitical and “always carried the germ of murder in it, simply because it is the enemy of plurality.”

Scholem, on the other hand, had claimed the Judaic tradition as his world. His studies on Jewish mysticism put sects and movements previously regarded as too obscure and notorious for serious consideration at the very heart of historical Judaism. Yet it was precisely through them that he affirmed both the essential value and vitality of the Jewish nation. Mysticism, with its potentially explosive religious content, was not a fleeting construction but “an essential determining force of the inner form of Judaism.”

Like Arendt, who wrote perceptively about the figure of the Jewish pariah, he was interested in fissures, conflicts, and paradoxes. He probed subversive figures such as Shabbtai Tzvi and Jacob Frank, but these investigations all took place within a foundational structure. Like Arendt, too, Scholem’s early political preferences for Palestine were binationalist, and he belonged to the binationalist group, Brit Shalom. But his commitment to a collective Jewish renaissance and (an admittedly idiosyncratic) Zionism did not waver when the possibility of a binational Arab-Jewish state appeared foreclosed. This Zionist vision, cut out of organic Judaic materials, did not sit well with Arendt’s more skeptical modes of identification.

It was, of course, around the question of Zionism that Arendt and Scholem’s first serious conflict emerged. This was occasioned by Arendt’s fierce 1945 article “Zionism Reconsidered” in The Menorah Journal. In the article, Arendt argued that, unlike previous resolutions, that of the American Zionist Convention in October 1944, demanding “a free and democratic commonwealth . . . [which] shall embrace the whole of Palestine, undivided and undiminished,” had entirely omitted to mention the Arabs, and simply left “them the choice between voluntary emigration or second-class citizenship . . . It is a deadly blow to those Jewish parties in Palestine that have tirelessly preached the necessity of an understanding between the Arab and the Jewish peoples.”

However, the terrible catastrophes in Europe had rendered the majority of Zionists ever more narrowly nationalist and chauvinist. In so doing, she argued, Zionists had created their own “insoluble ‘tragic conflict,’ which can only be ended through cutting the Gordian knot.” A nationalism that insisted upon one’s own exclusive sovereignty and that relied only upon force and, indeed, the force of outside powers, would lead to intractable conflict. Such an emergent national state would appear to be a tool, an agent of foreign and hostile interests, a fact that—she rather presciently noted—will “inevitably lead to a new wave of Jew-hatred.”

Arendt also criticized Zionism for what she regarded as its unpolitical and unhistorical notion of an “eternal” Jew-hatred leading to “utter resignation, an open acceptance of anti-Semitism as a ‘fact,’ and therefore a ‘realistic’ willingness not only to do business with the foes of the Jewish people but also to take propagandistic advantage of anti-Jewish hostility.” Central to her polemic here was a withering attack on the Nazi-Zionist transfer agreement. She also attacked the kibbutz movement as a Utopia “on the moon” whose supposedly visionary elite only sought to recreate the socio-political conditions of other nations. Finally, she argued that “the Zionists shut themselves off from the destiny of the Jews all over the world,” through their negation of the Diaspora and the belief that the galut was destined to disappear.

In a letter written on January 14, 1945, she warned Scholem of what was coming. She had been hard at work on “a principled reconsideration of Zionism, as I am of the earnest opinion that if we continue like this, everything will be lost.” This formulation implied that the criticism derived from her own involvement in the movement and a sense of concerned familial identification. “On the other hand,” she added, “this may cost me my last Zionist friends if they are fanatic.”

As it happens, in his youthful diaries, Scholem had proudly described himself as a “fanatic.” It was partly as such a self-confessed “fanatic” and partly as a pained friend and ideological relative that he couched his angry, well-wrought reply to Arendt. In a letter of January 28, 1946, a “disappointed” and “embittered” Scholem expressed his surprise that given her own Zionist affiliations, Arendt’s critique was based “not on Zionist but rather extreme . . . anti-Zionist grounds.” As much as the content of her arguments (each of which he sought to refute), at stake too was the question of the limits of loyal, connected criticism. Arendt, he observed, had indiscriminately combined all the old charges against Zionism (its imperialist, reactionary character, its exploitation of anti-Semitism, its narrow sectarianism, etc.). It was a jumble, he wrote, written from the standpoint of a “communist critique, transposed into an incoherent Golus-nationalism” and a universal morality that existed in practice nowhere but in the heads of disaffected Jewish intellectuals. Despite his earlier advocacy of a binational solution, Scholem told Arendt:

I would vote with an equally heavy heart for a binational State as for partition. The Arabs have not agreed to one solution, be it federal, statist or binational, when it is connected to Jewish immigration. And I am convinced that the confrontation with the Arabs on the basis of a partition fait accompli will be easier than without.

Arendt’s argument that members of the Yishuv (the pre-State Jewish community in Palestine) were not interested in the fate of the Jewish people was simply absurd and though the transfer agreement raised ethical dilemmas, Scholem’s only regret was that—as this was the only possibility of rescue from the hands of fascism—they had not been able to save more Jews with it. “I confess my guilt,” he replied:

with the greatest calm to most of the sins you have attributed to Zionism. I am a nationalist and fully unmoved by apparently progressive declarations against a view that since my earliest youth has been repeatedly declared as superseded . . . I am a ‘sectarian’ and have never been ashamed to present my conviction of sectarianism as decisive and positive.

In her long answer of April 21, 1946, Arendt insisted that her arguments did not flow from “an anti-Palestine” complex but rather an alarmed concern for it. She had nothing against nationalism itself but rather its organization into political states that could easily transform nations “into a race-horde . . . an enduring danger in our time.” For all that, she added to Scholem, “I can’t stop you being a nationalist, although I can’t quite see why you are so proud of it.” Arendt’s critique sounds almost contemporary; the basic terms of debate remain seemingly unchanged.

She concluded her reply by expressing a concern that their angry dialogue—an “orgy of honesty” she called it—could threaten their friendship. She herself did not feel wounded by the harsh exchange but, perhaps as “masculini generis,” she bitingly noted, Scholem was more vulnerable. Human relations, she pleaded, were ultimately more important than differences of opinions.

Arendt was certainly right to note that Scholem was a man who did not enjoy being contradicted, but he also worked hard to maintain their friendship. Most of this time, they kept their ideological tensions under control through occasional familiar Yiddishisms like “tachles,” witty barbs against common targets such as Scholem’s “Love thy Buber as thyself,” or careful silence (the name Martin Heidegger does not appear in any of the letters). Most often, however, it was their mutual commitment to the memory of Walter Benjamin that held their friendship together. Whenever disagreements arose, they reverted to Benjamin, and the ways in which they could advance his publications and good name, which was then virtually unknown. They both regarded Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, the leading figures of the “Frankfurt School” of neo-Marxist critical theory, who had been Benjamin’s erstwhile colleagues and patrons, as the enemies, determined to monopolize, misconstrue, or even hide Benjamin’s work.

Meanwhile, in the years after World War II, Scholem and Arendt both worked independently for the Jewish Reconstruction Committee (JRC), that great project to rescue Nazi-looted Judaica. Arendt generously cooperated with Scholem to ensure that Israel’s National Library received the bulk of pillaged literature recovered by the JRC. A great deal of the correspondence deals with the strategies, legal and bureaucratic difficulties, and political intrigues of this complicated, heroic enterprise. (A useful history of the JRC, by David Heredia, is included as an appendix, after the letters.)

In December 1951, when the JRC had completed its work, a dinner was held honoring Arendt, and Scholem requested that the following words be read out:

I am proud to think how lucky JRC has been in having her serve as head of staff. I am an old friend and admirer of Miss Arendt as an engaging personality and masterly intellect, but in this latest phase of her career she has revealed even greater qualities: her sensitiveness and understanding, her energy that knew no bounds, and her devotion to the task have been of the highest value. I shall always remember with the greatest pleasure this period of our common work. We have shared the excitement of digging for the lost treasures of the Jewish cultural heritage; we have shared the hopes and disappointments involved and also the joy of discovery and recovery.

Their disagreements were more or less held in check until Arendt wrote Eichmann in Jerusalem. She was sent to Jerusalem by The New Yorker to cover Eichmann’s trial, and she was coming, she flippantly wrote Scholem, to “amuse” herself. Actually, Arendt did not spend all that much time in the courtroom itself, nor, curiously, did she see Scholem. As far as I can ascertain, it appears that Scholem was not in Jerusalem at the time. In any case, they did not meet. Arendt did meet with other intellectuals, including Leni Yahil, and political figures such as Golda Meir, but their discussions did little to temper her views—(in fact, they may have made them more extreme). Given Scholem’s stature and the history of their relationship, one wonders whether his presence would have changed Arendt’s thinking, or at least her tone. In the end, one doubts it. Arendt later admitted to Mary McCarthy “that I wrote this book in a curious state of euphoria. And that ever since I did it, I feel light-hearted about the whole matter. Don’t tell anybody; is it not proof positive that I have no ‘soul’?”

Taken separately, none of Arendt’s main claims in the Eichmann book were entirely original.

Already in 1940 the young German journalist Sebastian Haffner had written of the Nazi perpetrators: “The doer does not fit the deeds. The enormity is committed by extraordinarily banal, weak, and insignificant men . . . No different are their bureaucratic colleagues who sit in offices and torture their victims by methods less physical and palpable, but no less effective.” Others, too, had criticized the ways in which Israel and the prosecution conducted the trial. Even her claim that the Jewish Councils were complicit in the murder of their own people was not new, although her counterfactual formulation was extraordinarily harsh:

The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and a half and six million people.

It was, however, the combination of these claims, the American forum in which they appeared, the international publicity they generated, the apparent callousness of their formulation, and, above all, the affiliated Jewish identity of the famous author that generated such outrage.

Scholem first answered Arendt’s charges in a private letter dated June 23, 1963. While such close proximity to the catastrophe made objectivity impossible, he stated, the difficult issues must indeed be confronted. Yet Arendt’s constant insistence upon Jewish weakness in the face of the Nazi assault acquired “overtones of malice.” He wrote:

The problem, I have admitted, is real enough. Why, then, should your book leave one with so strong a sensation of bitterness and shame—not for the compilation, but for the compiler?

The letter resounds with Scholem’s shock that someone whom he regarded “wholly as a daughter of our people, and in no other way,” could express such convictions, convictions that were so lacking in love for the Jewish people (ahavat Yisrael). This sense was only exacerbated for Scholem by Arendt’s harsh remarks, such as that concerning Leo Baeck, “who in the eyes of both Jews and Gentiles,” Arendt proclaimed, “was the Jewish Führer.” (She also described Eichmann as “a convert to Zionism.”) As for the Jewish Councils, Scholem argued for a more forgiving view of their impossible predicament:

Some among them were swine, others were saints . . . There were among them also many people in no way different from ourselves, who were compelled to make terrible decisions in circumstances that we cannot even begin to reproduce or reconstruct. I do not know whether they were right or wrong. Nor do I presume to judge. I was not there.

Arendt’s thesis that the Nazi compulsion of the Jews to participate in their own extermination blurred the distinction between torturer and victim, Scholem proclaimed, was “wholly false and tendentious . . . What perversity! We are asked, it appears, to confess that the Jews, too, had their ‘share’ in these acts of genocide.” To be sure, Scholem argued, if the Jews had indeed run away, “in particular to Palestine—more Jews would have remained alive. Whether, in view of the special circumstances of Jewish history and Jewish life, that would have been possible, and whether it implies a historical share of guilt in Hitler’s crime, is another question.”

In her reply to Scholem, Arendt declared that “I have always regarded my Jewishness as one of the indisputable factual data of my life, and I have never had the wish to change or disclaim facts of this kind.” Yet with regard to Scholem’s comment regarding “love of the Jewish people,” she exclaimed: “I have never in my life ‘loved’ any people or collective . . . the only kind of love I know and believe in is the love of persons . . . This ‘love of the Jews’ would appear to me, since I am myself Jewish, as something rather suspect. I cannot love myself or anything which I know is part and parcel of my own person.”

Clearly the divide between them was great, yet when Scholem suggested that these letters be published, Arendt assented adding: “The value of this controversy consists in its epistolary character, namely in the fact that it is informed by personal friendship.”

But it was precisely the personal friendship that made the argument so painful. Scholem’s commitment to Jewishness was unconditional; Arendt took pride in the complex, even subversive nature of her intertwined commitments. As she commented about her non-Jewish, second husband, Heinrich Blücher: “If I had wanted to become respectable I would either have had to give up my interest in Jewish affairs or not marry a non-Jewish man, either option equally inhuman and in a sense crazy.”

She delighted in publicly challenging collective narrative and national memory. Her defenders regarded this as a matter of intellectual principle and honesty, her critics viewed this as a kind of tactless perversity, indeed, as a kind of Jewish anti-Semitism. The controversy became so fierce that at one point Arendt told Mary McCarthy that there was “a war between me and the Jews.” Scholem, it should be pointed out, specifically did not join those who accused Arendt of “self-hatred.” Nevertheless, it was this controversy that brought the correspondence and their friendship to an end.

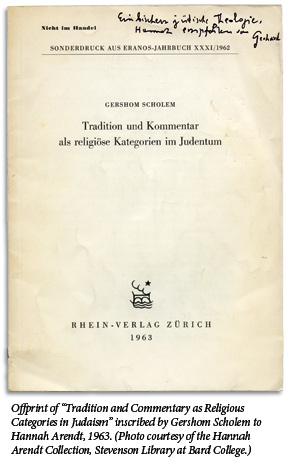

There is a final irony here. Throughout her career, Arendt reflected beautifully on the nature and critical importance of friendship. Truth, she declared in her moving essay on Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, should be sacrificed to friendship and humanity. Yet—and this is the climactic surprise of the correspondence—it was she and not Scholem who declined to continue the friendship. Intriguingly, at more or less the same time that their Eichmann controversy raged, Scholem made sure to send Arendt his inscribed article on “Tradition and Commentary.” The final letter of the correspondence, dated July 27, 1964, is from Scholem. Addressed to “Dear Hannah” and closing with “Heartfelt Greetings,” it informs Arendt of his forthcoming trip to New York to deliver a lecture on their friend Walter Benjamin. “In case you will be in New York,” he wrote, “and if we want to see each other again, this is the given moment.” That moment was never to be.

Suggested Reading

Necessary Power: A Rejoinder to Jonathan Sacks

When Rabbi Sacks writes, “It is not our task” (and it was not Abraham’s task) “to conquer or convert the world or to enforce uniformity of belief. It is our task to be a blessing to the world. The use of religion for political ends is not righteousness but idolatry,” it seems to me that he oversimplifies matters.

You Say You Want a Revelation

Who's afraid of biblical criticism?

No Joke

Sigmund Freud loved Jewish jokes and for many years collected material for the study that would appear in 1905 as Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. An excerpt from Ruth Wisse's new book No Joke: Making Jewish Humor.

Light Reading

Stoicism and the human heart.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In