If God Wills It, a Broom Can Shoot

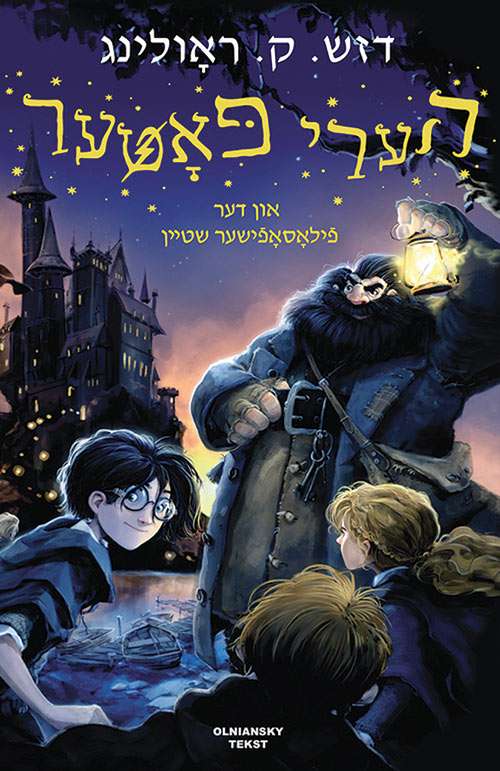

Call him Voldemort,” Dumbledore had told Harry. “Always use the proper name for things.” “Ruf im Voldemor. Zolst tomid onrufn a zakh mitn geherikn nomen.” This was my primary directive as I attempted to translate the characters and objects of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone into Yiddish.

Take, for example, the name Slytherin, a house at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, whose mascot is a serpent and whose students and alumni—from Draco Malfoy to Bellatrix Lestrange to Voldemort himself—are known for cunning and ruthlessness. Initially, I saw only two possibilities: either a close phonetic approximation such as Sliderin or a literal translation of the verb “to slither,” something like Shlengelin. I went back and forth for weeks, unsure of which was better, feeling out how each sounded and remaining unsatisfied. Then, I was struck by a completely different solution that immediately felt right: Samderin, composed of two words—sam and derin—that together mean “venom within.”

Quidditch, on the other hand, the name of the popular wizarding sport in which players flying on brooms throw balls through hoops, seemed like it could work well enough once the “qu” was replaced with a “kv.” And yet, I found myself drawn to the old saying az got vil, shist a bezem, which means, “If God wills it, a broom can shoot.” I condensed shist a bezem into shisbezem (literally “shootbroom”) and knew that I had discovered Quidditch’s proper name in Yiddish.

Of course, some terms required little or no modification: Muggle, Hufflepuff, and Bludger already sounded at home in Yiddish, and Ravenclaw and the Hog’s Head pub found their direct translations in Robnkrel and Khazer-Kop. But beyond individual words, I was faced with a bigger challenge: bridging the gap between the world of Yiddish, with its culture and personality, and that of the magical British boarding school of Hogwarts. The variety of Yiddish dialects and registers worked surprisingly well when mapped onto the Hogwarts faculty: Hagrid spoke like a backwoods Galitzianer; Snape and McGonagall were severe, buttoned-up Litvaks; and Albus Dumbledore was a lomdish rosh yeshiva, peppering his Yiddish with rabbinic Hebrew and Aramaic.

But other parts of the language were not such a good fit. For example, a Yiddish speaker (even an atheist) might punctuate a hopeful observation with the phrase “im yirtzeh Hashem” (if God wills it), and, though Harry and his friends are certainly full of optimism, I just couldn’t imagine them using a traditional Jewish formula to express it. After all, I wasn’t trying to create a Jewish version of Harry Potter; I was rendering J. K. Rowling’s novel into a Jewish language, and that was a very different enterprise. But how did I come to this enterprise in the first place? To understand that, we must go back to my childhood in the Modern Orthodox suburbs of New Jersey.

When I was 14, I pulled a hardcover book off the shelf entitled Antologye fun der yidisher literatur far yugnt (Anthology of Yiddish Literature for Youth) and flipped it open to a short story by I. L. Peretz. It was about a fisherman, I think, but I’m not sure because I couldn’t make it past the second paragraph. I struggled through the sentences at a painstakingly slow pace, sounding out unfamiliar words—valgern, hoyzgezind, shlaydert, umgekumen—before giving up and coming to the realization that I was barely literate in my mother tongue.

This was alarming. My sisters and I had been raised with the expectation that we one day would raise our own children speaking Yiddish. It was our family mission. My grandfather, Dr. Mordkhe Schaechter, whose own father had traveled 100 miles by foot in 1908 to attend the famous Czernowitz Conference on Yiddish, had committed his life to documenting and teaching the language. My mother was a Yiddish poet and the editor of a comprehensive English-Yiddish dictionary, and my aunts and uncles were all prominent figures in the Yiddish community. And yet, I couldn’t even make it through a simple story in a young adult anthology. I now know that my experience was not unique; many children who speak a minority language with their parents find themselves losing their grasp on their home language as they grow older, lacking the capability to fully express themselves and constantly being corrected by parents and relatives. But that didn’t make it any less terrifying. There was a real possibility that I might break the chain of transmission—and I couldn’t allow that.

I spent the next decade reading as much as I could in Yiddish and inputting each new word or phrase into a flashcard program on my computer. Reviewing these cards became a daily activity that I returned to at every free moment: in between classes during high school and college, on the subway, in line at the supermarket. Each right answer was a tangible indicator of my progress. And yet, somehow, the larger my digital stack of cards got, the more I discovered there was to learn.

Are you really intending to raise our kids,” my wife Tali asked me one Saturday afternoon after our Shabbes lunch, “in a world that doesn’t have Harry Potter in Yiddish?” I was hesitant. After all, I felt I was still recovering that which I had almost lost. Could I really rebuild J. K. Rowling’s expansive universe of magical spells and objects out of a flashcard vocabulary?

But Tali had set the challenge, and I couldn’t resist trying. I dove into the project, armed with dictionaries and in partnership with a publisher, two editors, a typesetter, and half a dozen informal advisors that included sisters, cousins, in-laws, and, of course, my wife. The deeper I got, the more I discovered that translation problems do not have definitively correct solutions that can be methodically uncovered. I had become so accustomed to the rigid and binary nature of my flashcards that I had forgotten what it was like to be in a dynamic relationship with Yiddish, to explore its sounds and shapes and shades with open-ended curiosity—and, sometimes, to innovate. Samderin for Slytherin was nowhere to be found in my flashcards or my mother’s dictionary, but it sounded right and felt good—and it was Yiddish.

Translating gave me permission to see not only Harry, Hermione, and Ron but also myself in Yiddish, not merely as a container to preserve and pass on, but as a living part of the language itself. What had seemed for so long to be a burden, however proudly I bore it, became a source of joy and energy—and I was finally able to understand why it is that my family has fought so hard to ensure the continuity of this wonderful language. When my children come along, I will be ready and excited to read them Harry Potter in a language that possesses a magic of its own.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

Why There Is No Jewish Narnia

So why don’t Jews write more fantasy literature? And a different, deeper but related question: why are there no works of modern fantasy that are profoundly Jewish in the way that, say, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is Christian?

Riding Leviathan: A New Wave of Israeli Genre Fiction

A new batch of Israeli fantasy books may not contain Narnias, but they pound on the wardrobe, rattling the scrolls inside.

Translating and Remembering Chaim Grade

A memoir of faith, literature, and chickens.

Paulette Millander

This is wonderful!

By translating Harry Potter into Yiddish, young kids will be inspired to use the language and keep it alive!

Rochelle Mogilner

The irony is that the largest Yiddish speaking populations are the chareidi ultra orthodox communities and their children most probably will not have access to this translation. It is ‘bitul Torah’for them and ‘se past nisht’ to read this in any language. However, ‘samderin’ is a wonderful choice for Slytherin as are the others. כל הכבוד!