“A Story of Commitment, Solidarity, Love Even”

In 1944, Hannah Senesh, a young, newly minted kibbutznik who was also a budding poet, parachuted as a British soldier into Yugoslavia and from there crossed back into her native Hungary to do what she could to help protect the country’s Jews from the Nazis. Caught near the border and tortured mercilessly, she refused to divulge any information about her mission to the Hungarian authorities, who eventually executed her. “In my youth,” Michael Walzer wrote 20 years ago, “Hannah Senesh was the great woman, and Marie Syrkin’s popular history Blessed Is the Match was the crucial text; the book worked its magic: the first time I brought my daughters to Israel, I took them to visit Hannah Senesh’s grave on Mt. Herzl.” But Walzer knew that times were changing. “I dread the revisionist assault,” he continued, “on Syrkin and Senesh.”

I remembered Walzer’s comment when I picked up Mikhal Dekel’s new book Tehran Children. The “Tehran children” made their way from Poland through the Soviet Union to the Iranian capital during World War II, until they were finally transported in February 1943 to Palestine, where they were joyously welcomed. This was one of the more heartening episodes in the history of efforts to save Jewish lives during the years of the Holocaust, and, like Walzer, I dreaded the prospect of Dekel’s revisionism. She was going to expose their rescue, I immediately suspected, as unseemly Zionist shenanigans. In her previous, densely written book, The Universal Jew: Masculinity, Modernity, and the Zionist Moment, the Haifa-born professor of English at CUNY, who had, in her words, moved “entirely outside the logos of the nation,” had sought to expose some of the defective roots of the Zionist idea. Now, it seemed, she had moved on to discredit one of the steps taken toward its embodiment.

But I was entirely wrong. Dekel identifies as someone who has absorbed, “like other students trained at American universities during the 1990s, the political scientist Benedict Anderson’s insight that nations were not historic, ancient entities, but ‘imagined communities,’ bound together by shared texts, images, and dates on the calendar,” and she has “spent years identifying how such communities were ‘constructed,’ ‘imagined,’ and ‘manipulated.’” But this model, Dekel tells us, is inadequate for her current subject. This inadequacy is in part because the views on Israel prevailing in her scholarly milieu had begun to irk her, and, as dissatisfied with her native country’s policies as she continued to be, she often found herself defending, albeit “halfheartedly, what I called home and what many of my friends called ‘the Zionist project.’” And it is in part because her new research was about her own family—not the product of an academic agenda but the outcome of her personal history. It is a belated attempt to grapple with the fact that one of the Tehran children had grown up to become her father.

Dekel’s father, Hannan, had rarely spoken to her of his earlier life, and by the time she began work on her book, he was no longer alive, but his sister Regina (in Israel, Rivka), who had also been a “Tehran child,” was. Dekel’s account is mostly based, however, on what she could glean from books, archives, and travels to the most important stations on her father’s routes (excluding, of course, Iran). Her research involved a considerable amount of detective work and benefited from some extraordinary good luck. She knew, for instance, that her father, like the other children, must have been interviewed when he arrived in Palestine in 1943. Still, she couldn’t find evidence of that anywhere—until she happened to attend a panel on children’s war testimonies at an academic conference in Boston. After she heard one of the participants read from the testimony of a 15-year-old named Chananja Teitel (her father’s original name), “the rest of the panel was a blur.” The speaker didn’t have the full transcript, but she told Dekel where to find it: in “a tiny, messy, strangely fascinating archive at the heart of the Gur Hasidic community in Bnei Brak.” That night Dekel sent an email to the archive, and the very next morning, she received a reply that included a photo of “eight yellowing pages.”

Dekel’s story begins in the Polish town of Ostrow Mazowiecka, where her paternal ancestors had resided for eight generations. Her family’s prosperity rested on the success of their popular brewery. Leading figures in the town, the Teitels were fairly assimilated, still somewhat observant, and committed Zionists, though, except for a cousin, who was a student at the Technion, they were not inclined in the 1930s to leave Poland for Palestine. After the Nazis invaded, in September 1939, Dekel’s father and his brother packed their families and everything else that they could into two trucks and fled eastward to territory newly occupied by the Soviets.

Things were so bad there for Dekel’s grandparents Zundel and Ruchela that they actually signed up their family to be returned to German-occupied territory. That’s where they thought they were headed when they were rounded up by NKVD men, thrown onto a “Red Cow” cattle car, and transported to Siberia as slave labor. Terrible as this was, it was better than what they had asked for. And they had it better than some others who shared their fate since they had been able to bring with them coats that “would mitigate the frost and minus-50-degree-Celsius temperatures that would arrive in winter.” They were lucky, too, to have only eight people in their barrack. These were small consolations, however, when the brutal winter of 1940 came. “The frost,” Dekel writes, “caused Hannan to lose sensation in his fingertips, a sensation he never regained, though I had not previously known when it happened.”

Released from their “special settlement” in “the gulag universe,” following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Teitels headed for Central Asia. By November 1941, they had been resettled in a poor kolkhoz (collective farm) in Uzbekistan, but Zundel quickly arranged to have the family smuggled out and then steered them to Samarkand, a magnet for hundreds of thousands of refugees, many of whom found themselves sleeping in its streets. Zundel, again, did better; he eventually found a “straw and mud hut” at 24 Jangirabackaia Street, an address Dekel succeeded in locating 70 years later. The building had by then been improved, but the owner could point out an interior wall still made of mud and straw, and told Dekel that “her baba had told her many times that refugees had lived there.”

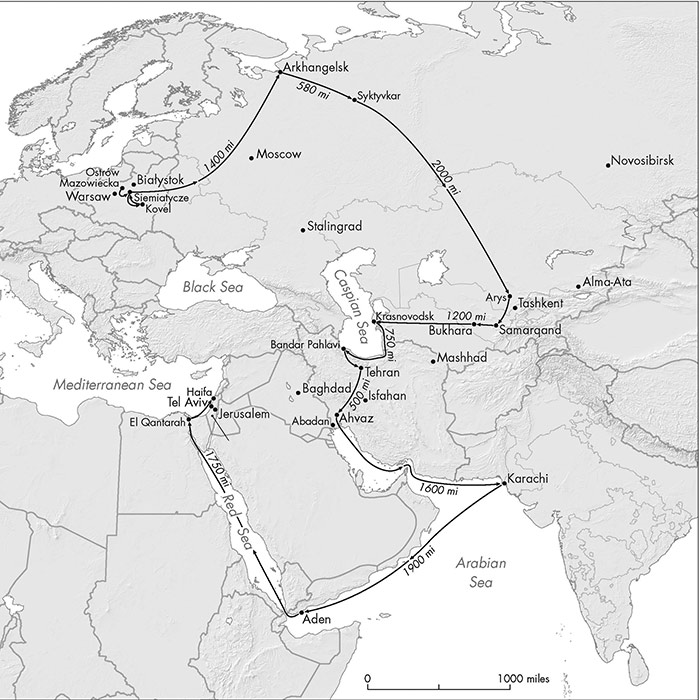

Dekel’s grandparents remained in that hut for several years, but her father and aunt, after being placed in an orphanage, were lucky enough to be among the thousands of Polish refugee children (a thousand of them Jews) who were evacuated in 1942 to Iran. They traveled there together with General Anders’s Polish Army-in-exile, composed mainly of ex-prisoners (including Menachem Begin). Dekel poignantly imagines their last moments in Samarkand, walking silently alongside their emaciated parents, who were trying to save them from starvation by sending them “penniless and parentless, possibly forever, to an uncertain future and a country they could not point to on a map.”

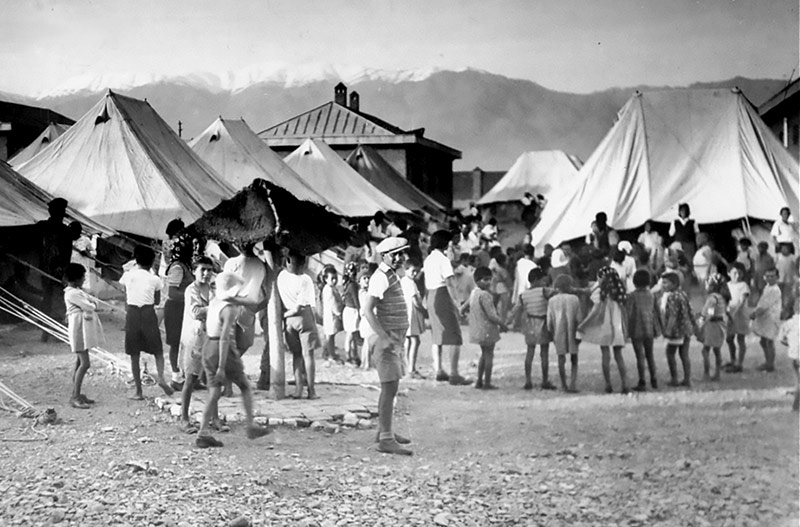

Some of the children with whom they crossed the Iranian border died of malaria and typhus en route; the rest arrived in Tehran with hair lice, ringworm, scabies, and diarrhea. Once they were there, however, the children found themselves in good hands and were nursed back to health in a Jewish orphanage established by the local Jewish community. By September 1942, the Jewish Agency was able to obtain immigration certificates for them to enter Palestine, and the Joint Distribution Committee was ready to pay for their transportation. The remaining hurdle was the opposition of the Iraqi government to their passage through its territory to Palestine, a hurdle that Moshe Shertok (later Sharett) succeeded in overcoming by devising a 48-day roundabout voyage through the Persian Gulf to Pakistan, back west again to Egypt, and, in the end, across the Sinai by train. The children finally arrived in Palestine on February 19, 1943. By May, the Teitel children, together with a cousin who had made the journey with them, had been taken by one of Zundel’s cousins to live in Kibbutz Ein Harod.

Dekel describes her book as “a new kind of Holocaust history, a new kind of second-generation memoir of my father’s Holocaust.” What most interests me is that when she turned to the topic closest to her, she very consciously put aside the ideological lenses through which she had previously approached history. Even if she doesn’t use them, however, they are not too far away.

She tells us, for instance, how in Uzbekistan she met Nina, an 83-year-old Polish-born woman, “a Polish-Jewish girl turned Uzbek.” In Samarkand, Nina had long ago married an Uzbek worker at the shoe factory where they both worked, and eventually became a beloved “Jewish-Muslim matriarch.” “Had she replaced her Polish-Jewish identity for an Uzbek-Muslim one,” Dekel wondered, “while my father and his sister and cousin had reclaimed their ‘original’ Jewish identity in Israel? Or was the identity of the refugee something more fluid?” And “If your family cares for you with such tenderness in old age, does it really matter if you end up in a brick house in Samarqand or a luxury condo in Tel Aviv?”

Her father and aunt “would have balked at the comparison,” she thought, but when she was next in Israel she told her aunt about Nina, to which her aunt replied:

You come to a place, you have no one. You meet a guy, and he behaves nicely and accepts you, and brings you to his family, and they are good people. So you ask yourself: what am I going to look for?

Dekel asks her aunt whether she could imagine her own life “in Russia or Uzbekistan or in Iran or elsewhere but Israel” and is surprised and pleased to find that she could.

There are other occasions on which Dekel muses about the accidental character and mutability of nationality, but more often, she takes note of its enduring strength. As she retraces her family’s route from Poland to Palestine, she talks with the locals—some quite knowledgeable and some not—about the tensions between the Jews and their neighbors in the past as well as the present. She also read thousands of documents pertaining to the Polish government-in-exile, which revealed precisely what she hoped not to see: “the exclusion of Jews from resources and from their very identity as Poles, and concurrently a denial of this exclusion by Polish authorities.”

Conversely, Dekel was deeply impressed by the evidence she found of a sense of Jewish mutual responsibility all over the world. In the past, she had always thought of the JDC as a somewhat hapless organization. After learning, however, of the efforts it had made to assist the wartime Jewish refugees in Central Asia, she “was amazed by the ingenuity and expediency with which the JDC purchased and shipped the medicines, and by the commitment and urgency with which it acted.”

I now knew what my father had never known: that in faraway continents and cities—New York, London, Mexico City, Montreal, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Jerusalem—many highly competent and devoted persons worked incessantly to try to save him.

There was help from closer by, too. When the children and other refugees showed up in Tehran, the local Jewish communities bent over backward to help them. By the end of 1942, according to a JDC report, these communities “would contribute more to the relief of the Jewish refugees in ‘larger amounts, both in cash and kind, than have the JDC and the Jewish Agency together.’”

Reading this, I thought of the 17th-century situation described by Adam Teller in his recent Rescue the Surviving Souls (which I reviewed in our Spring 2020 issue). Then, too, benefactors from all over the world chipped in to help Polish Jews who had been carried off to the East, and then, too, the local Jewish communities reached deep into their pockets to redeem them. One 20th-century difference—an enormous one—was the fact that one of the Middle Eastern Jewish communities prepared to help was the embryonic Jewish state based in Palestine, and it could do so with more than money.

Saul Meirov, the legendary head of the Jewish Agency’s clandestine immigration arm, went to Iran, where he launched border-crossing operations to aid the refugees still in the Soviet Union. As one agent later testified, “We made tremendous efforts to smuggle ourselves through the border, but we did not succeed. There were casualties. Emissaries were killed. It didn’t help. They [the Soviets] guarded the border.” The border could be penetrated by packages, however, and Meirov’s team mailed as many as they could to their trapped brethren. This, Dekel tells us, “was a story of commitment, solidarity, love even: packages that ‘rescued from illness, death, and arrest,’ packages that ‘kept people alive and helped them maneuver their situation.’”

Even while they were stranded in Samarkand, Zundel and Ruchela were kept abreast of their children’s progress in Palestine. The archives preserve a copy of a respectful, reassuring, and utterly remarkable letter sent to them in August 1943 by the legendary head of Youth Aliyah, Henrietta Szold. Reading it, Dekel was “moved that Szold had addressed the man who she well knew was a starving, lice-ridden refugee as ‘Herr Teitel’ [in Yiddish, not German].” She was moved, most of all, “by the letter’s content: the polite report, the solicitation of parental consent for the education of their offspring. . . . It was as if Szold was still preserving, in 1943, the contours of a world of legal norms, logic, politeness, and cordiality, while every norm, every convention, and life itself would soon be completely annihilated.”

Nonetheless, Dekel’s research has not brought her back to what she describes as the unreflective Zionism of her youth, when Israel was for her “a thing to love and defend and never question, an absolute safehaven, a guarantee against the violence of others.” Whatever sympathy she now has for the logic of nationalism is tempered by her understanding of “the price that was paid for those who remained outside the fold of the nation, for those who were targeted as its enemies and its threat, for the violence begat by the nation.”

She does not think, however, that the path to wisdom lies in a guilt-ridden eschewal of national identity. Rather, she writes:

The only way around being locked in an eternal focus on your own people’s victimization . . . was to first and foremost feel it, take in the pain of it, the humiliation, the starvation and helplessness that my father never had the privilege of acknowledging, that few Israeli survivors and their offspring had. And after that pain, there should come attention to history, to time, to change: to persons and groups that come together, grow apart, and come together again; to fates that are redealt and reshuffled over the course of history; to dialogues that sometimes, with some people—the challenge is to figure out which—may continue despite rifts and even momentary hatred. It was the only way out of a binary thinking that cast one side as eternal victim and the other as eternal enemy.

In Tehran Children, Dekelsucceeds, to an extraordinary degree, in evoking her parents’ pain as well as in provoking reflection on the nature of belonging. Precisely because her book avoids any facile conclusions, it leaves an indelible impression. It does so also because of its disarming frankness. In the introduction, Dekel tells us how deferentially and tenderly her father had always treated his mother Ruchela, from whom he had been separated during and after World War II. When Dekel was growing up, her grandmother lived in a little room off the kitchen in the family’s Haifa apartment, and the extraordinary attention her father paid to his mother unsettled her: “When I was six or seven and had just learned to write, I composed a letter to my father, asking why he loved his mother more than us.” This infuriated her father and had long-lasting aftereffects. At the very end of the book, after we have heard her family’s story and seen how her grandfather Zundel died, a broken man in Poland, Dekel takes us back to that apartment in Haifa, “with its quiet yet breathtaking views of the Mediterranean,” where “a girl of six or seven, raised in what I now knew were relative privilege and safety and care, asked her father why he loved his mother more than her.”

Suggested Reading

Where To: America or Palestine? Simon Dubnov’s Memoir of Emigration Debates in Tsarist Russia

Dubnov's magisterial autobiography, written while Dubnov was in exile from both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, takes the reader on a deeply personal journey through nearly a century of upheaval for the Jews of Eastern Europe. A new translation.

Confusion and Illusions: 1939

In their new book, Jehuda Reinharz and Yaacov Shavit focus on the efforts of the leaders of a diverse and disunited Jewish people in Europe, the United States, and Palestine to cope with this crisis in the years leading up to World War II.

Original Sins

John Judis book about Truman's Middle East policy isn't a rant, but it's not exactly history either.

Cri de Coeur

The Short, Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan: A Boy Avenger, a Nazi Diplomat, and a Murder in Paris.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In