Where To: America or Palestine? Simon Dubnov’s Memoir of Emigration Debates in Tsarist Russia

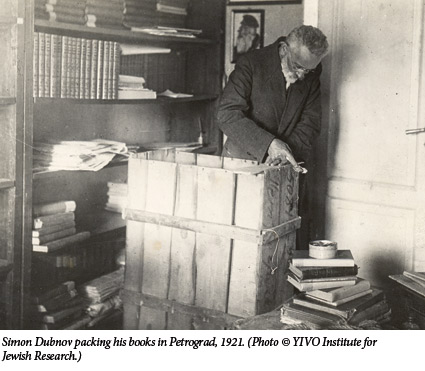

Simon Dubnov (1860-1941), whose name is often spelled “Dubnow” to yield the correct pronunciation in German, was one of the 20th century’s most influential historians of the Jews. Like Gershom Scholem and Jacob Katz, he transformed not only what we know about the Jewish past, but the way we understand what “history” means for a diasporic people. In his native Russia, Dubnov was both a well-known historian and an engaged public intellectual whose best-selling works recast the Jewish past and its relevance to the present.

Dubnov’s magisterial autobiography, Kniga zhizni; vospominanīia i razmyshlenīia. Materīaly dli a istorīi moego vremeni. (The Book of Life: Memoirs and Reflections. Materials for the History of My Time), published in Riga between 1934 and 1940 while Dubnov was in exile from both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, takes the reader on a deeply personal journey through nearly a century of upheaval for the Jews of Eastern Europe. This excerpt is taken from the new English translation by Dianne Sattinger, edited and annotated by Benjamin Nathans and Viktor Kelner, forthcoming from the University of Wisconsin Press.

My youthful radicalism also found expression in journalism. At that time [1881] the burning question was which direction the emigration of Jews from Russia should take. Refugees from the pogrom-plagued south had rushed to the German and Austrian borders with the goal of emigrating to America, but then the plan of colonizing Palestine arose. Certain eccentrics even proposed a plan of resettlement in Spain. I took a stance on this question in the article “The Question of the Day” (Rassvet [The Dawn, a Russian-language Jewish weekly newspaper published in St. Petersburg]). It was easy to deal with the Spanish proposal: an economically underdeveloped country of Catholic monks, where the law forbidding public worship by non-Catholics still had not been revoked, could not serve as a haven for Jews. For mass immigration, Palestine too was unsuitable, with its despotic Turkish regime and primitive Arab population, with its Jewish pilgrims, hostile to modern schooling and to all attempts at agricultural colonization. Only one destination was left: the great democracy of North America. There, in the sparsely settled states, broad expanses of land could be acquired for cultivation and for creating a whole network of farming colonies. Here I cited the declaration of the Parisian “Alliance Israélite” that only America was suitable for emigration, as well as the initiative of the Union of American Jewish Congregations, which had just established a collection of funds to buy land for Jewish settlers. Remarkably, at that time we all had agricultural colonization in mind and not urban industrial immigration . . .

I do not know how much my article, one of the first on the emigration question, contributed to this result; I merely know that after its appearance a lively debate took place on the pages of Rassvet and Russkii evrei [The Russian Jew, another weekly published in St. Petersburg] about the question “Where to”: America or Palestine? The first advocates of Palestinism expressed their opinions, and two months after the publication of my article, Moshe Leib Lilienblum also came forward in Rassvet with heavy artillery in the well-known article “The All-Jewish Question and Palestine,” in which the new pro-Palestine ideology was developed for the first time. I recall how the secretary to the editor, Markus Kagan, who was in favor of emigration to Palestine, showed me the manuscript of Lilienblum’s article immediately after it was received. Before revealing it to me, he posed an insidious question: “Well, what do you think—what position will Lilienblum take on the emigration question?” I answered: probably in favor of America. Then and there he opened the manuscript and triumphantly tapped his finger on its concluding lines. At that time it could not have entered my mind that the author of Sins of Youth, my teacher in all things radical, would hurl a challenge at European progress and turn his face to the East. That summer I had the opportunity to express my opinion on yet another cultural question, much less urgent at the time, but which later became the subject of passionate debates. [Alexander] Tsederbaum, the editor of the Jewish weekly Hamelits in Petersburg, conceived the idea of also publishing a weekly in Yiddish, or as people used to say, in “jargon,” under the title Yidishes folksblat [The Jewish/Yiddish People’s Paper]. When an announcement about the publication arrived at Rassvet‘s editorial office, [associate editor Mark] Varshavskii suggested that I write a special article about how necessary such an organ was, and he advised me to speak personally with Tsederbaum . . .

On a summer day I rang the doorbell at Tsederbaum’s apartment on Liteinyi Prospect. I was greeted by a graying, slightly hunchbacked, diminutive old man, who bore very little resemblance to that mighty “cedar” (erez) by which he pseudonymously dignified himself at Hamelits. I was curious to speak with the editor of the once-militant organ that had unmasked rabbinic and Hasidic fanaticism, whose articles I had read with such enthusiasm in earlier years, but the conversation with him disillusioned me. The garrulous old man recounted at length his pursuits and achievements, including the Yiddish-language Kol Mevaser [Voice of the Messenger], which he published in the 1860s in Odessa, and the conflicts he had had with contributors to his publications: [Sholem Yankev] Abramovich (Mendele), [Avraham Ber] Gottlober,Lilienblum. We parted amicably, and I could not then foresee that a couple of years later this old denouncer would sharply attack me, a young denouncer, after the appearance of my articles about religious reforms. Under the influence of our conversation, I wrote a short anonymous article titled “A Newspaper for the Jewish People” (Rassvet 1881, No. 35), where I passionately demonstrated the necessity of creating serious journalism in the language of the people, which both “our nationalists and cosmopolitans” treated with equal scorn. The new organ was especially important given the disarray of the masses in the wake of the pogroms, when the common folk needed to know what to do, where to emigrate, and how to refashion their livelihoods on the basis of “productive labor,” whether agricultural or artisanal. “The main goal of a newspaper for the Jewish people,” I wrote, “should be to foster serious discussion of social problem—and not via sarcasm or humor, as has hitherto been the case.” In general, the new organ fulfilled our expectations. During the 1880s it grouped around itself a number of young writers who later became famous, such as [Mordechai] Spektor, Sholem-Aleichem, and [Simon] Frug, but within the newspaper there were never-ending debates about the equality of rights “jargon” should have with Hebrew and Russian. At that time I advocated only tolerance toward the Jewish vernacular; it was only much later that I came to acknowledge its equal worth.

On a summer day I rang the doorbell at Tsederbaum’s apartment on Liteinyi Prospect. I was greeted by a graying, slightly hunchbacked, diminutive old man, who bore very little resemblance to that mighty “cedar” (erez) by which he pseudonymously dignified himself at Hamelits. I was curious to speak with the editor of the once-militant organ that had unmasked rabbinic and Hasidic fanaticism, whose articles I had read with such enthusiasm in earlier years, but the conversation with him disillusioned me. The garrulous old man recounted at length his pursuits and achievements, including the Yiddish-language Kol Mevaser [Voice of the Messenger], which he published in the 1860s in Odessa, and the conflicts he had had with contributors to his publications: [Sholem Yankev] Abramovich (Mendele), [Avraham Ber] Gottlober,Lilienblum. We parted amicably, and I could not then foresee that a couple of years later this old denouncer would sharply attack me, a young denouncer, after the appearance of my articles about religious reforms. Under the influence of our conversation, I wrote a short anonymous article titled “A Newspaper for the Jewish People” (Rassvet 1881, No. 35), where I passionately demonstrated the necessity of creating serious journalism in the language of the people, which both “our nationalists and cosmopolitans” treated with equal scorn. The new organ was especially important given the disarray of the masses in the wake of the pogroms, when the common folk needed to know what to do, where to emigrate, and how to refashion their livelihoods on the basis of “productive labor,” whether agricultural or artisanal. “The main goal of a newspaper for the Jewish people,” I wrote, “should be to foster serious discussion of social problem—and not via sarcasm or humor, as has hitherto been the case.” In general, the new organ fulfilled our expectations. During the 1880s it grouped around itself a number of young writers who later became famous, such as [Mordechai] Spektor, Sholem-Aleichem, and [Simon] Frug, but within the newspaper there were never-ending debates about the equality of rights “jargon” should have with Hebrew and Russian. At that time I advocated only tolerance toward the Jewish vernacular; it was only much later that I came to acknowledge its equal worth.

Suggested Reading

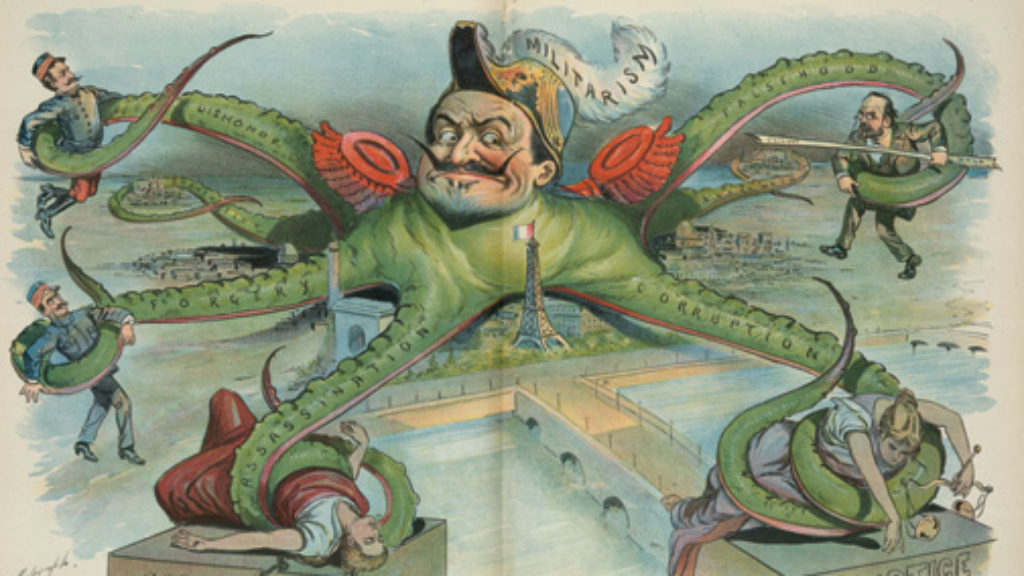

An Affair as We Don’t Know It

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit.

In and Out of Time

A new collection of Heschel's writings plucked from obscurity and presented with clarity to English readers adds to our understanding of the centrality of time in Heschel’s worldview.

Haim Gouri at 90

The poet turned 90 last fall, and his latest poems are among the best he has ever written.

Friendship in the Fields of Moab

Naomi and Ruth have mourned together and are now setting off on the 50-mile journey from the plains of Moab to Bethlehem, toward an uncertain future—alone but side by side.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In