The Mayor and the Massena Blood Libel

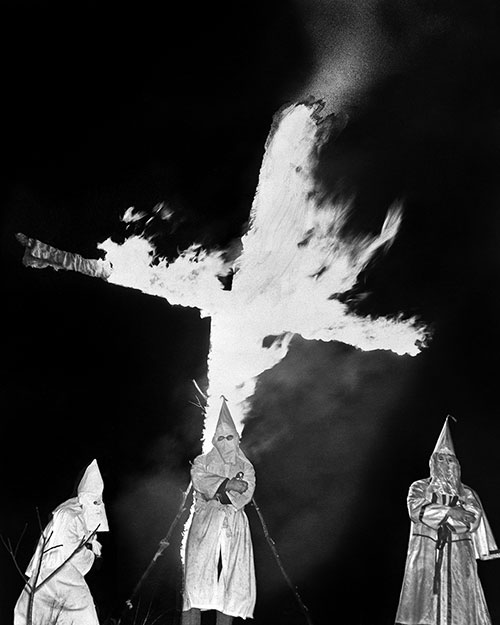

On September 22, 1928, two days before Yom Kippur, four-year-old Barbara Griffiths disappeared in the woods outside Massena, New York, a village of 10,000 residents on the Canadian border. A rumor quickly spread that echoed the vilest of antisemitic tropes of the Old World: Barbara had been kidnapped and murdered by the town’s Jews, who needed the blood of a Christian child for some depraved holiday ritual. The Massena blood libel might have started with “a Greek café owner,” an unidentified “foreigner,” a “French Canadian,” or “firefighters belonging to the Ku Klux Klan.” Whoever first suggested it (swapping the old calumny about Passover for one about Yom Kippur in the process), it quickly took hold.

As the search for the missing girl went on, firefighters and villagers shone flashlights into the cellars of Jewish businesses, looking for her body. Instead of immediately squelching the false and fantastical rumors, Massena’s mayor, W. Gilbert Hawes, authorized the police to investigate them. With Hawes’s blessing, state troopers summoned Massena’s rabbi to the town hall, where, after making his way through an agitated crowd, he was interrogated about the Jews’ alleged propensity for human sacrifice on religious holidays. Fearing an imminent pogrom, Massena’s small Jewish community frantically reached out to prominent Jewish leaders in New York City for help.

And then the black cloud passed, almost as quickly as it had appeared. Barely 24 hours after her initial disappearance, Barbara emerged from the woods, unharmed, and was reunited with her overjoyed parents. No one had done her ill; she had simply lost her way and fallen asleep, exhausted, in the tall grass. Yet if Barbara’s ordeal was over, the story of the Massena blood libel was just taking flight. Exploding onto the front pages of newspapers across the country, it briefly became a cause célèbre, as shocked and shaken Jews expressed their outrage.

The story has now been admirably retold in Edward Berenson’s The Accusation: Blood Libel in an American Town. Berenson, a professor of history at New York University, was born in Massena and heard about the incident from his grandparents, one of the 20 or so Jewish families who lived in the town at the time. Compactly framed and soberly presented, his highly readable account stands as an important corrective to the other book-length treatment of its subject, Saul Friedman’s overwrought and (according to Berenson) unreliable The Incident at Massena: Anti-Semitic Hysteria in a Typical American Town, published in 1978.

In assessing what the Massena incident says about “the place of Jews in American life” and how “American attitudes about Jews compare with European ones,” Berenson sharply disagrees with Friedman’s central thesis. Friedman claimed Massena revealed a “cesspool” of antisemitic hatred deep in the soul of Christian America. In Berenson’s judgment, this “turns the truth on its head”: in fact, he writes, “the Massena blood libel ultimately showed that American civilization, at least in relation to its Jewish population, was stronger than many people thought.”

Surely Berenson is right about this. As is true of other antisemitic episodes in American history, such as General Grant’s famous order expelling Jews from parts of Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee during the Civil War, what is most extraordinary about the Massena incident is its quick, forceful condemnation by Jews and non-Jews alike. Just as Paducah, Kentucky, merchant Caesar Kaskel, despite having emigrated from Prussia only four years earlier, immediately hopped a train to the nation’s capital to protest General Grant’s un-American order directly to President Lincoln, so too did Massena’s Lithuanian-born rabbi, Berel Brennglass, vehemently protest the gross prejudice with which he was confronted. When state trooper Corporal H. M. “Mickey” McCann asked if it was true that Jews offered human sacrifices on holy days, the diminutive rabbi responded with a tongue-lashing that may have reminded McCann, a veteran of the Great War, of his drill sergeant.

“I am dreadfully surprised,” Brennglass barked, “to hear such a foolish, ridiculous and contemptible question from an officer in the United States of America, which is the most enlightened and civilized country in the world. Do you realize the seriousness of this question?” To which McCann could only meekly reply that “a foreigner” had told him so. “It is a false and malicious accusation,” Brennglass assured him, adding, “We shall have to know who the foreigner is, he is dangerous and should be taught a lesson that he is in the United States of America.” Imagine a rabbi giving such a lecture to a uriadnik in Russia or a policjant in Poland, where, as Berenson recounts, the blood libel continued its tragic and murderous path well into the 20th century and even after the Holocaust.

Two days after Barbara’s reappearance, a contingent of officials including Hawes, McCann, McCann’s boss, and the town attorney showed up at Massena’s synagogue to offer their apology in person. The apology was not accepted. The congregation’s leaders felt the matter was now in the hands of the national Jewish leaders they had alerted, Louis Marshall of the American Jewish Committee and Dr. Stephen S. Wise of the American Jewish Congress. Hawes then wrote a defensive letter to Dr. Wise expressing “regret” if he had caused any offense to the Jewish people, but Wise found it “too vague to constitute an apology.” At Wise’s urging, Governor Alfred E. Smith, at the time also the Democratic nominee for president, convened a hearing in Albany to investigate the investigators and how they had come to pursue what Smith called the “absurd” claim of ritual murder.

At the end of the hearing on October 4, Hawes finally issued a formal written apology that satisfied Wise. Hawes admitted he had committed “a serious error of judgment” and expressed “clearly and unequivocally” his “deep and sincere regret” that he had “seemed to lend countenance, even for a moment, to what I ought to have known to be a cruel libel imputing human sacrifice as a practice now or at any time in the history of the Jewish people.” “Far from giving hospitable ear to the suggestion,” Hawes’s apology continued, “I should have repelled it withindignation and advised the state trooper to desist from his intention of making inquiry of the respected rabbi of the Jewish community of Massena concerning a rumor so monstrous and fantastic.” Corporal McCann issued his own written apology the same day, addressed to Rabbi Brennglass, saying he was “very, very sorry for my part in the incident at Massena” and now realized “how wrong it was of me to request you to come to the police station at Massena to be questioned concerning a rumor which I should have known to be absolutely false.”

If the substance and cadence of these apologies sound like they could have been dictated by Stephen S. Wise himself, that is for good reason: they were. Ironically, in the most notorious blood-libel incident in American history, the propagators of the ritual murder myth served as its public debunkers. Only in America, it could be said.

“Why Massena, New York?” Professor Berenson asks. “And why there but nowhere else in the United States—and at no other time?” Here, Berenson’s analysis is less satisfying.

To begin with, Berenson’s premise is incorrect. Massena is not “America’s only known instance of blood libel,” as The Accusation’s book jacket claims. Blood libels had happened before, if infrequently—in New York City in 1850, for example, when hundreds of Irish immigrants ransacked a synagogue after rumors that Jews had murdered a Christian girl for her blood; in Clayton, Pennsylvania, in 1913, when a 16-year-old Slavic servant in a Jewish household feared she was about to be sacrificed on the eve of a bris and went into hiding, prompting claims she had been killed by Jews; in Chicago in 1919, when a mob demanded that a Jewish businessman surrender a Polish boy supposedly locked inside his dry goods store; and in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, that same year, when a Polish boy cut after falling from a tree falsely claimed that Jews had abducted him on the street, dragged him into a synagogue, and drained two bottles of blood from his leg.

The Accusation spends much of its time far away from Massena, offering a brief history of the blood libel itself, with detailed accounts of numerous specific European examples dating back to the accusation against the Jews of Norwich, England, in 1144. Curiously, however, Berenson does not describe the other American blood libels at all. He dismisses them as “isolated accusations” that provoked “little community response”—without explaining how Massena was any different, and without mentioning the strong local reaction the incidents provoked. In 1919, for example, Chicago’s Jews complained to the police, as a result of which the leader of the mob and 17 of his cohorts were prosecuted. Massena is the most famous American blood libel, but it is not the only such incident, or, arguably, even the most serious one.

Berenson’s answer to the question “Why Massena?” focuses on the wave of immigrants who came to Massena around the turn of the century, attracted by the job opportunities offered by a local power canal and Alcoa’s new aluminum plant. Many of the new immigrants were from Italy, Greece, Poland, Romania, and Hungary, where the blood libel remained part of the folk culture. Many others were French Canadians from nearby Quebec, where anti-Jewish agitation and violence ran high in the 1910s and 1920s, with the ritual murder accusation figuring prominently in antisemitic literature.

But the source of the Massena blood libel is not the most interesting or important question raised by the incident. What makes Massena unique is that Mayor Hawes, the town’s top public official, gave the rumor credence and authorized the police to investigate it and interrogate the town’s rabbi. Berenson, however, says little about Hawes. And much of what he does say is wide of the mark, judging from information about Hawes culled from local newspapers, including the Massena Observer, and other sources.

Berenson describes Hawes as a “prosperous dairy farmer who had married well and become a wealthy man” and quotes Wise’s observation that Hawes had “a K.K.K. ‘ponim.’” The impression thus created—of a bigoted country bumpkin—bears little resemblance to reality. Hawes was in the dairy business, but he wasn’t a “farmer.” He owned and operated a dairy plant, H. & H. Dairy, which sold milk, cream, and butter. It was the first plant to pasteurize milk in Massena. Hawes did not, then or ever, live on a farm; as Berenson notes, he and his family occupied one of Massena’s oldest and most expensive houses, located in the center of the village.

The dairy was only one of the mayor’s business interests. He also owned a trucking and transport business. And he had recently purchased and planned to revive a once-famous health center at the site of Massena’s natural mineral springs (he was already bottling and selling spring water tapped from the site). He was a cofounder and director of a cold storage plant and an ice cream manufacturing business, and he was an organizer and director of two different banks: the Massena Banking and Trust Company and the Massena Savings and Loan Association. Hawes was also the president of the Massena Chamber of Commerce.

A relative newcomer to Massena, Hawes was born into a prosperous family in Tarrytown, New York. The Hawes family traced its lineage to Edward Hawes, a Puritan who immigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636. His many descendants included leading citizens of Massachusetts and New York, active in the Revolutionary cause. Lieutenant Joseph Hawes, for instance, fought at Concord and Bunker Hill authored Wrentham’s declaration of independence, which was issued June 5, 1776, and served in the Massachusetts legislature. A century later, the Hawes were still prominent. Mayor Hawes’s father, Charles F. Hawes, acted as an agent for a major English fire insurance carrier covering Southern New York, New Jersey, and western Connecticut. He was later promoted to head agent for New England, and the family moved to Newton, Massachusetts, where Hawes attended high school.

As a young man, Hawes was more early 20th-century yuppie than yahoo. He worked in America’s two most cosmopolitan cities: in Boston, for a railroad company, and then in New York, for a bank. When he married, he and his wife moved to New Rochelle, New York, which was already a tony suburb of Manhattan, with a significant Jewish population (it housed both Orthodox and Reform synagogues). Hawes did not arrive in Massena until 1918, when he was 31 years old.

Berenson suggests that Massena’s native-born residents were particularly susceptible to anti-Jewish messages in 1928 because they were still reeling from the town’s sudden transformation “from a largely agricultural community of Protestant, ‘old-stock’ Americans to an industrial boomtown with an ethnically and religious diverse population of Catholics, Protestants, Greek Orthodox, and Jews.” Berenson also cites the “religious passions” unleashed by that year’s presidential campaign following the Democratic Party’s nomination of Al Smith, a Catholic. These are plausible hypotheses, but they have little if any explanatory power as applied to Mayor Hawes. Having never experienced life in preindustrial Massena, Hawes had no reason to be nostalgic for it. Indeed, in his businesses and as mayor, Hawes was an agent of modernization. Nor was he likely to have been so inflamed by the Republican anti-Catholic rhetoric of 1928 that he suddenly fell sway to religious bigotry. Hawes first ran for office as a Democrat, unseating the Republican incumbent, and he was a member of the relatively tolerant Congregational church.

There is, of course, no reason to believe that Hawes was immune from the common prejudices that led to widespread discrimination against American Jews, especially those from Eastern Europe, in the early 20th century. But there is also no evidence prior to the blood-libel incident that he harbored any deep-seated anti-Jewish hatred. Hawes served alongside Joseph Stone, a prominent Jewish businessman, on the boards of the Massena Chamber of Commerce and the Massena Savings and Loan. The two men were also vice-chairmen of a charity committee. He sat with Isaac Friedman on the board of the Massena Banking and Trust Company and appointed Sam Shulkin, the brother of Willie Shulkin, whose interrogation helped ignite the incident, to serve on a Chamber of Commerce committee. “I have daily business intercourse with Jews and am on friendly terms with them,” Hawes said when defending himself during the scandal.

Hawes also claimed his “best friends” growing up were “mostly Jewish boys.” Berenson ridicules that claim as “certainly false” since Tarrytown’s tiny, strictly Orthodox Jewish population at the time was “unlikely to associate with Gentiles.” But this may be unfair, since Hawes spent much of his teens and early adulthood in places with less insular Jewish communities, such as Newton, Boston, Brooklyn, and New Rochelle. Even assuming its mayor was no philosemite, Berenson acknowledges that Massena was a place where the Jewish community “complained little of hostility to Jews” before the blood-libel incident.

So why did Mayor Hawes indulge such a pernicious and ludicrous stereotype about his town’s Jews? As Berenson says, we’ll never know precisely why. In his apology to Dr. Wise, Hawes claimed that his “serious error of judgment” was precipitated in part by “the excitement incident to the disappearance of the Griffith child of my community.” Corporal McCann, in his apology, similarly blamed the pressure of the situation, claiming he was “terribly excited and fatigued at the time, having been on duty for many hours without food or rest.” Self-serving and inadequate, to be sure, but these excuses find a measure of corroboration in the observations of George Gordon Battle, a New York City lawyer who attended the hearing in Albany on behalf of the AJC. Writing to Wise, Battle described Hawes and McCann as “unfortunate men” who had acted “through ignorance and weakness, rather than through malice.”

In one sense, that verdict is comforting; in another, it is profoundly disturbing. Individualism, capitalism, rationalism, religious tolerance—these are the quintessentially American traditions and values thought to have stifled the growth here of the kind of virulent European-style antisemitism that gave rise to the blood libel. Hawes’s life experiences and family background suggest he was fully steeped in those traditions and values. And yet, as an elected official in 20th-century America, he flirted, however briefly, with an accusation of Jewish ritual murder. If the crisis had continued—if little Barbara Griffiths had not resurfaced so quickly—would Hawes’s New World sensibilities have kicked in and kept a lid on brewing barbarism? Fortunately, the Jewish community of Massena never had to find out.

Suggested Reading

Fateless: The Beilis Trial a Century Later

The fame of Mendel Beilis—falsely accused of murdering a Christian boy in Russia 100 years ago—was lavish, if bitter and short-lived.

The Mortara Affair, Redux

Bologna, 1857: A six-year old is taken from his Jewish family to be raised a Catholic. Why are we still talking about this case? An archbishop responds.

Untrue Blood

There was a common idea behind ritual murder and host desecration accusations: Jews were imagined to be re-enacting the crucifixion.

The Child Was Circumcised

The circumcision controversy in Germany has been heating up, but it's not the first time. The discussion has been going for centuries and has involved differing levels of overt anti-Semitism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In