Blood Delusion

In the latest example of the “paranoid style in American politics,” so-called QAnon conspiracy theorists have been circulating rumors of a vast Democratic-Hollywood cabal to kidnap children and murder them in order to imbibe their blood. This myth got its start with the “Pizzagate” story in 2016 in which Hillary Clinton was alleged to be orchestrating a pedophilia ring centered improbably in a Washington, DC, pizza shop. But where fantasies of ritual murder are concerned, the Jews cannot be far behind, and, indeed, George Soros has featured prominently in some of these vampiric tales.

The blood libel lurks in the historical background of these calumnies; the QAnon obsession with child abduction and murder could, and largely does, flourish without Jews. Thus, before turning to the blood libel’s importance in Jewish history, we should remember that anxiety over the safety of children is natural, even if such worries can metastasize into bizarre fantasies. We should recall the epidemic of false accusations against child care centers in the early 1990s for practicing satanic rituals on the children in their care. In a grim reminder of medieval and early modern blood libels, some of the accused in these cases ended up with long prison sentences.

The earliest allegations of ritual murder were not aimed at Jews but at early Christians, whose celebration of the death of Jesus and symbolic consumption of his blood led some pagans to assume that Christians actually committed murder and drank the blood of their victims. It was only in the 12th and 13th centuries, for reasons still debated, that these accusations were turned against Jews. In 1144, during the week leading up to Easter in the city of Norwich, England, a boy named William was murdered, and the Jews were accused, apparently for the first time, of murdering an innocent Christian child for ritual purposes. As would become the subsequent practice, the victim was turned into a saint, starting with miracles such as his corpse smelling sweet. Such accusations became a way of reenacting the passion of Christ, especially around Easter—and, perhaps not so incidentally, producing a profitable pilgrimage site.

A hundred years later, in Fulda, Germany, and Valréas, Provence, blood was added to this imagined ritual, with the Jews now accused of needing Christian blood for various purposes, such as the making of matza or curing the wound of circumcision. Although the Jews of Norwich had been protected from a trial by ordeal by the sheriff, who took them into a kind of protective custody at Norwich Castle, the Jews of Fulda, Valréas, and other European towns and cities were not so fortunate. In what would become a pattern, some were murdered by angry mobs, and others were executed after trials that typically involved torture.

The belief that the Jews need blood for their rituals presupposed that they reenacted the consumption of Christ’s blood in the eucharist sacrament—but for malign, even demonic reasons. While the blood libel was rooted in Christianity, it also accused Jews of practicing precisely the opposite of what Judaism itself teaches, namely, not to consume blood. This accusation is similar to the medieval images of Jews suckling from, as well as committing heinous sexual acts with, pigs, another blatant inversion of Jewish teaching. Indeed, antisemitism, medieval and modern, typically claims that “real” Jews engage in esoteric practices that are the opposite of “official” Judaism. The myth’s power lies in the belief that Jews are part of a secret conspiracy whose tracks they hide by pretending that they do and believe the opposite.

The blood libel flourished in the Middle Ages as a local myth, rather than one rooted in church teaching. In the 13th century, the Vatican came down firmly against the ritual murder accusation, repeatedly noting that Jews do not consume blood of any kind. While this dynamic would remain more or less the same over the subsequent centuries, in the early modern period, the subject of Magda Teter’s deeply researched and engaging history, a subtle shift occurred that made it possible for these local forces to assert themselves much more aggressively.

The medieval and early modern blood libel has been researched by several fine historians, notably Gavin Langmuir, Miri Rubin, and R. Po-chia Hsia. Teter, a historian of Jewish-Christian relations in early modern Poland, builds upon this literature, but she also has something new to say. Like Hsia, she focuses much of her attention on a blood libel case from 1475 in Trent, Italy, when a small boy named Simon turned up dead in a canal under a Jew’s house. She convincingly argues that this was a kind of “hinge” case that transformed the medieval blood libel into its early modern incarnation. Trent’s geographical location, on the border between Italy in the south and the Holy Roman Empire in the north, was a key factor. While ecclesiastical authorities in Italy, and especially in the Vatican, followed medieval precedent in throwing cold water on ritual murder accusations, the bellicose German prince-bishop of Trent, Johannes Hinderbach, agitated vigorously for the torture and execution of the Jewish suspects, then created a barrage of propaganda over the case. Hinderbach had two interlocking goals: to defame the Jews and to produce a saint who would put Trent on the pilgrimage map. In doing so, Hinderbach got into a royal battle with the Vatican, which, following medieval practice, was inclined to protect the Jews. But after Trent, the Vatican became far more reluctant to fulfill its medieval role.

In addition—and here is where Teter makes a striking contribution—the new technology of printing fundamentally changed how the (fake) news of the event was received and disseminated. Hinderbach and other writers flooded the market in Germany and Poland with descriptions of the case and illustrations in what Teter calls “a sophisticated multimedia propaganda campaign.” Some of these accounts were still in circulation in the 20th century. Teter shows how German accounts of the Trent case made their way to Poland and served, in her view, as a primary cause of the many blood libels that occurred there between the 16th and 18th centuries. One sign of the long reach of Trent could be found in the Polish town of Sandomierz, more than 1,300 kilometers away, where frescos on the walls of the church portrayed the murder of little Simon, thus making the story available even to the illiterate.

The 16th century witnessed the decline of blood libel cases in Central Europe even as they rose in Poland. It is possible that the Reformation played a role in diminishing belief in such myths (Protestants who rejected the ritual of communion were less likely to imagine that Jews secretly performed a secret satanic anticommunion), but Catholic Poland did not undergo such disenchantment. The rise of Christian Hebraism also increased the number of people among the Central European intellectual elite who knew that the Jews were actually prohibited from imbibing blood. This kind of knowledge was less available in Poland, where few works of Christian scholarship about Judaism circulated. But the Catholic Church itself also underwent a significant development, which pulled in the opposite direction. In 1583, the Vatican allowed Simon of Trent to be considered a martyr and, in 1588, endorsed his cult, although he was never made into a saint. No longer were popes publicly vocal in defense of the Jews, a shift that must have had an impact in Poland. Teter does a masterful job of excavating Vatican archives to provide one of the most in-depth accounts of this increasingly anti-Jewish papal policy.

In 1755, Pope Benedict XIV endorsed the cult of Andreas Oxner von Rinn, a boy who died in the 15th century and whose death local folklore had blamed on the Jews. Reversing earlier policy, the pope now affirmed that the Jews did, indeed, perpetrate ritual murder. At the same time, however, a cardinal named Lorenzo Ganganelli was commissioned to write a report on such purported crimes. Following medieval Catholic dicta, he decisively rejected the idea that the Jews needed Christian blood. Interestingly, Ganganelli, like other church officials who rejected the blood libel, did so less for philosemitic reasons than for the opposite: such accusations, trials under torture, and grisly executions made it harder to convert Jews. But, as Teter shows, Ganganelli’s report was hidden in the archives and only resurfaced by accident at the end of the 19th century when a new wave of blood libels swept Central Europe.

As an historian of the Jews, Teter is also interested in the Jewish response to the history of such accusations. She points out that, surprisingly, Sephardi writers were more likely to address the blood libel, even though almost all the cases were from the Ashkenazi world. Texts such as Solomon ibn Verga’s Shevet Yehudah typically end the tales of these accusations with the Jews emerging triumphant. For example, Ibn Verga quotes agents of King Alfonso, who are sent to investigate an attempted ritual murder: “Last year, in this matter, they also accused [Jews] but it turned out to be a lie.” By contrast, when Ashkenazi writers did address the libel, they usually highlighted the Jewish victims as martyrs, thus mirroring the child martyrs of the libel. Adil Kikinesh of Drohobycz, for instance, confessed falsely to convincing her Christian maid to kill a Christian boy to obtain blood for the Passover matza. Steadfast in her modesty, she requested pins to attach her skirt to the skin of her legs so that they would not be exposed to onlookers on the way to her execution. Her fabricated confession saved her community, and she was celebrated on her tombstone as “the holy and pure woman who sanctified the great name and gave her soul for all Israel.”

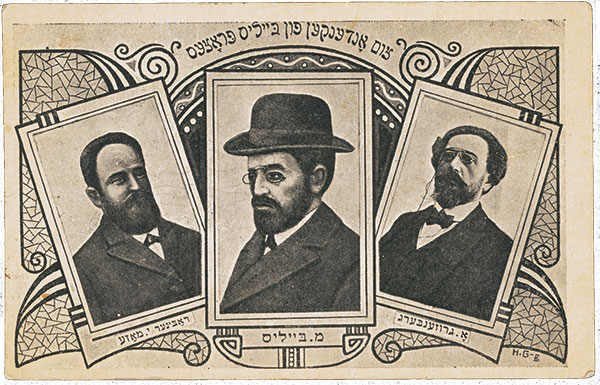

Teter’s history of blood libel really ends in the 18th century and doesn’t seek to explain the emergence of new accusations in the 1880s, culminating in the infamous 1911–1913 case in Kiev in which Mendel Beilis was accused of killing a Christian boy for his blood. The judges exculpated Beilis but asserted that such ritual murders do, indeed, take place. The Beilis trial is usually seen as the end of a string of modern ritual murder trials. In Weimar Germany, attempts to revive the libel typically resulted in the Jews turning the tables on their accusers, suing them for libel. In the Nazi period, Julius Streicher, publisher of the semipornographic Der Stürmer, tried to make ritual murder an integral part of Nazi antisemitism, even resurrecting the iconography around Simon of Trent, but it never really stuck. Nazis found the accusation that Jewish men were obsessed with “defiling” Aryan women more useful. For reasons we can only guess, the new, racial antisemites were obsessed more with Jews injecting their impure blood into Christians than they were with Jews extracting blood from them.

Yet, as Elissa Bemporad teaches us in her concise and compelling book, blood libel and ritual murder had an afterlife in the Soviet Union and the “bloodlands” of the Holocaust. As she writes:

It is difficult to fully grasp the dynamics of violence unleashed during World War II in the region of Eastern Europe, which comprised present-day Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, without integrating the historical violence and memories of violence that earmarked Jews. The blood legacies played a central role in the carnage of European Jewry and made the Bloodlands likely.

Bemporad sets out to trace this blood legacy. In the tsarist period, blood libels were often connected to pogroms, that is, to mob violence, and Bemporad argues that the wave of pogroms during the Russian Civil War (1918–1921), which actually dwarfed those of the 19th century, cannot be understood without understanding the persistence of mythic beliefs about the Jews, including the blood libel. The myth of Judeo-Bolshevism added fuel to this fire. Indeed, one of the strongest aspects of this book is to remind us how the memory of the pogroms reverberated among Soviet Jews and created a loyalty to the regime that had initially made antisemitism a crime. In Bemporad’s apt phrase, pogroms became “sites of memory” for both Soviet Jews and the regime. The first Soviet government imprisoned the prosecutor in the Beilis case and executed Vera Cheberiak, the real murderer.

Nonetheless, the widespread belief in the Jews’ ritual use of blood persisted in Russia during the 1920s and even into the 1930s. An accusation in Minsk in 1937, Bemporad argues, may have taken part of its momentum from the wild conspiracies that Stalin’s purge trials evoked. After all, if stalwart Bolsheviks could be accused of spying for Western countries, why couldn’t the Jews be involved in ritual murder? And since circumcision and ritual slaughter were banned by the Soviet state, perhaps the Jews were carrying on other, more hidden rituals. However, these accusations never amounted to much in the 1920s and 1930s, and, most significantly, they rarely provoked pogroms.

And, yet, violent attacks on Jews of the sort that would have earned them the name of “pogrom” in the ancien régimedid occasionally take place. This was particularly true in Lvov, Poland, in the summer of 1945 after it was liberated by the Red Army. Ethnic Poles and Ukrainians incited riots by accusing Jews who were returning to their homes from wartime exile in central Asia of ritual murder and cannibalism. Although the Soviet authorities initially arrested those making the accusations, by spring of the next year, they dropped the charges for “lack of evidence.”

The Soviets’ failure to prosecute antisemitic pogromists in Lvov was one sign of a shift in the regime toward antisemitism. The notorious Doctors’ Plot of 1951–1953, in which Stalin accused a group of mainly Jewish doctors of plotting to kill Soviet leaders, was the culmination of a series of false accusations and political murders of Jews, including Yiddish writers. Bemporad’s contribution to this well-known history is to show that the belief that Jewish doctors were poisoning children was already a widespread folk belief, so in the Doctors’ Plot antisemitism from above converged with antisemitism from below. Indeed, many of these conspiracy theories were little more than secularized versions of the age-old blood libel. Even Stalin’s death, which put an end to the Doctors’ Plot, scarcely banished the belief in such myths from later Communist Russia and its post-Communist successor states.

The persistence of such beliefs in Russia, even in the face of state propaganda against them, makes one wonder why and how they persisted. Magda Teter makes a strong case that early print stories of Simon of Trent kept the idea of the blood libel alive and spread it to Germany and Poland. Yet, the material that Bemporad has assembled from more recent history suggests the importance of folk beliefs that circulate orally and, like a hardy bacillus, can survive even in a hostile environment (as the blood libel did in the Middle Ages when the Vatican repeatedly rejected it). A history of the blood libel must account for both literary and oral routes of transmission.

We also tend to focus primarily on blood libels against Jews, who have certainly been the primary victims of these bloodcurdling fantasies and for the longest time. But such malign beliefs are free-floating signifiers. They can attach to women accused of witchcraft and even to executioners, a taboo trade in early modern Europe. One of the most important defenses of the Jews against the modern blood libel was Hermann Strack’s The Jew and Human Sacrifice, which went through eight editions between 1891 and 1900 and was translated into many languages. Strack was intent on exculpating the Jews from the blood libel, but he also showed just how many strange and terrifying beliefs about blood one can find in folk culture throughout Europe and beyond. The blood libel drew its terrible energy from this wider set of beliefs. QAnon’s tales of secret blood-drinking rituals are just the latest incarnation of this old and ugly myth.

Suggested Reading

Fateless: The Beilis Trial a Century Later

The fame of Mendel Beilis—falsely accused of murdering a Christian boy in Russia 100 years ago—was lavish, if bitter and short-lived.

Revealer Revealed

Earlier this year, an email announcement of a publication made its rounds among scholars of Jewish studies. Written in the flowery Hebrew of the Eastern European Jewish Enlightenment, the advertisement proclaimed that the work would “reveal all secrets.”

Untrue Blood

There was a common idea behind ritual murder and host desecration accusations: Jews were imagined to be re-enacting the crucifixion.

The Mayor and the Massena Blood Libel

When State Trooper Corporal H. M. “Mickey” McCann asked if it was true that Jews offered human sacrifices on holy days, the diminutive rabbi responded with a tongue-lashing that may have reminded McCann, a veteran of the Great War, of his drill sergeant.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In