Zero-Sum Game

When I started reporting on Israel for the international press, I was made aware of linguistic quirks unique to this particular beat. One good example was the word “settlement,” which, in ordinary usage, means “a small village,” an isolated community out of Little House on the Prairie or perhaps colonial Rhodesia—but which we often used to describe suburban towns of 50,000 in the West Bank or certain neighborhoods in Jerusalem. A typical reader of the English language envisioned one thing, while the reality was another. Another quirk was our use of the word “capital,” which we refused to apply to Jerusalem, even though Jerusalem is Israel’s official seat of government, and that is the meaning of the word, which has nothing to do with international recognition. Or there was the word “disputed,” which we weren’t allowed to use for the West Bank, even though there’s obviously a dispute over the territory—the word “disputed” would make it seem like Israel might have a case. Our vocabulary was a kind of political code.

One of the most confusing examples was the word “refugee.” In describing the problems associated with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we regularly referred to “millions of Palestinian refugees,” summoning a clear image for Western readers—tents, camps, displaced people. The word “refugee” means “a person who flees for refuge or safety, especially to a foreign country,” but this wasn’t true of the vast majority of the people we were describing. So what were we talking about?

That very good question is the subject of a very good book, The War of Return: How Western Indulgence of the Palestinian Dream Has Obstructed the Path to Peace, by the Israeli journalist Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf, formerly a member of Knesset for Israel’s Labor Party. The authors, like most liberal Israelis (and like me), once believed the 1990s-era Western narrative about Israeli-Palestinian peace: that the Palestinians would eventually be satisfied with a state alongside Israel, that everyone desired the same kind of progress, that maximalist rhetoric on the Arab side masked more modest goals, and that the Palestinian talk about millions of refugees and their “right of return” to Israel was a starting position that was bound to be bargained away. We were all wrong, and in this book, the authors set out to explain why.

“Our book demonstrates,” they write, “that in the case of Israel and the Palestinians, decades of shuttling, strong-arming the sides, and endless hours of negotiations came to naught because none of the diplomats or negotiators truly understood and dealt with the root causes of the conflict, choosing instead to turn away and focus on that which appeared easier.” The part that appeared easier, they believe, was the route of the future border—which chiefly meant pressuring Israel to remove settlements. But all along, the real root causes, Schwartz and Wilf argue, were the Palestinian refugees and the desire of Israel’s enemies to use them and their descendants to reverse the very creation of Israel.

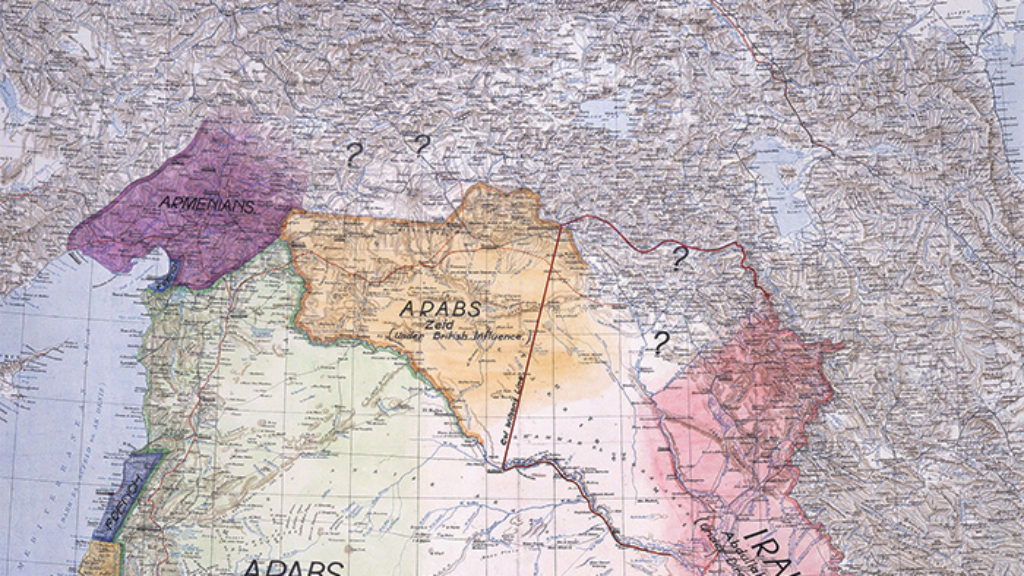

The War of Return isn’t a book about the refugees themselves. The authors don’t delve very deeply into the details of the genuine human tragedy of 1948—the uprooting of about 720,000 people amid the chaos of Israel’s war for independence, the shock of the Arab defeat, and the misery of a people living in limbo since then. Schwartz and Wilf are interested in the cold political use that has been made of the refugee issue by Israel’s enemies, and they present a political counterargument. They do so by tracing the evolution of the refugee problem—beginning not just from the 1948 war, but from the world of the first half of the 20th century, which was awash in displaced people of dozens of nationalities. There were the 1.2 million Greeks and 600,000 Turks of the 1924 population exchange between those two states, for example, or the 12 million ethnic Germans who became refugees after World War II, the approximately 14 million refugees of the India/Pakistan partition. That’s not to speak of the displaced Poles of Western Ukraine, the ethnic Bulgarians and Greeks of the 1919 transfer, and other groups that have been almost completely forgotten.

The transformation of the Palestinians into the world’s most famous and durable group of refugees, the authors write, had a lot to do with politics in the years immediately after 1948. This meant not just the Arab refusal to accept Israel’s existence, but the ulterior motives, misplaced sympathies, and naivete of some of the Western officials who set the contours of the conflict after Israel’s independence. Much in this part of The War of Return was new to me, particularly the Cold War’s importance in shaping refugee policy. The first years of Israel’s existence were also the ones in which the Arab world became an important arena of competition between the Western powers and the Soviet Union. If, wrote President Truman in 1948, “the Arabs are antagonized, they will go over into the Soviet camp.” And if Western funds weren’t funneled to the refugees, American officials worried, they could “provide fertile ground for social ferment and communist revolutions.”

Israeli leaders first assumed that the Arab refugees would eventually be absorbed into neighboring Arab countries, like the even larger number of Jewish refugees being absorbed by Israel just then, and like the millions of other people in the 1940s who were homeless and were obviously never going back to their original homes. But Israel’s first intelligence agents, Arabic-speaking Jews who were already undercover in the Arab world in 1948 and 1949, warned early on from Beirut and Amman that the refugees showed no inclination to resettle and that their Arab brothers showed no sign of helping them do so. This particular refugee problem was not about to go away.

Arab leaders weren’t coy about their plan. “It is well known and understood,” said Egypt’s foreign minister Muhammad Salah al-Din, “that the Arabs, in demanding the return of the refugees to Palestine, mean their return as masters of the Homeland and not as its slaves. With greater clarity, they mean the liquidation of the State of Israel.” With that being the case, the fragile new state—which numbered only about 600,000 Jews at its founding—couldn’t allow the entry of a large hostile population. The Arab world, for its part, wouldn’t resettle the displaced people because that would be admitting defeat. That deadlock has only been magnified over the seven ensuing decades, with the price paid by the hapless Arab civilians formerly of Lod, Haifa, and Jaffa, who’d lost their homes permanently, would never get them back, and would never be assisted in moving on. Instead, they would exist in a kind of suspended animation as human weapons in a failed war against the Jews.

In this coherent and well-argued account, responsibility for the initial transformation of the displaced Palestinians and their descendants into perpetual refugees is attributed in part to Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish UN mediator in 1948. Bernadotte sought to placate the Arabs by forcing the Israelis to give up some of what they’d managed to eke out in the bitter fighting, setting the tone for many subsequent Western interventions. It was Bernadotte (before he was killed by Jewish Lehi assassins in September 1948) who defined the return of Palestinian refugees to their original homes as a “right”—even though no such right exists in international law or was ever suggested for the millions of other refugees in the world at the time, including Jews, and even though it meant suicide for the new Jewish state. “Rather than set in motion a process that would ultimately lead to peace,” the authors write, “Bernadotte opened the door to a protracted war under the cloak of international legitimacy.”

The most fateful move on the part of the international powers was the creation of the UN Relief and Works Agency, or UNRWA. This was a bureaucracy tailored specifically for Palestinians, one which would remain separate from the UN agency in charge of the rest of the world’s refugees. Schwartz and Wilf make the interesting point that UNRWA was not the original name: the organization was to be called the Near East Relief and Works Agency, but the Arab side insisted on the inclusion of “UN” to make clear that the international community owned this problem.

In an indication of how things might have worked out in the Palestinian case, a different UN agency set up around the same time for another group of refugees, the 3.1 million people displaced by the Korean War, wrapped up its work within a decade with the resettlement of all refugees in South Korea. It then ceased to exist. But in the Middle East, this was not to be. The Palestinians and the Arab states, with Western acquiescence and money, made sure that UNRWA refugee status would be passed on first to the children of the refugees, and then, incredibly, to all descendants. It’s this move that created the ever-expanding “refugee” population now numbering over five million, seven times the original number, nearly none of whom would qualify as refugees by the UN’s own definition in any case but this one. (The number of original refugees from 1948 who are still alive is usually estimated in the tens of thousands.)

The peculiarity of the logic becomes apparent if applied to other instances. My grandfather, for example, was a child refugee from the 1914 Russian advance on Lemberg, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He wandered penniless on the roads of Europe and never saw his home again. By the logic of UNRWA, as the grandson of a refugee, I’d qualify for international aid 106 years later. My descendants would continue to qualify until it became possible to reclaim my family’s original property in what is now the Ukrainian city of Lviv.

The Western donors who began footing the bill early on told themselves they were helping the refugees, who’d be educated in UN schools and treated in UN clinics and would eventually move on to better lives. But the refugees themselves thought the UN agency was entrusted with getting their original homes back and were furious at any hint that this wasn’t going to happen. Just a few days after the agency’s founding, the authors tell us, its director in Nablus was attacked by the very people he was supposed to be caring for, and his driver was beaten. The word “resettlement” was forbidden. There was no alternative to “return.”

People in the West, and many Israelis, have had trouble understanding all of this and have dismissed it as irrational. But the authors disagree: the Palestinian position is consistent and must be taken seriously. “Their supreme concern—above any humanitarian considerations—was not to recognize the state of Israel,” they write of the refugees. “They subordinated their own living conditions to the wider struggle against the state of Israel. They saw the living conditions of hundreds of thousands, and later millions, of their people as less important than this political objective.”

That’s how we arrived in 1966, 18 years after Israel’s creation, at the discovery that about 15,000 PLO fighters were getting food and aid from UNRWA as they pursued the destruction of Israel (and this before the Six-Day War and the occupation of the West Bank, which is now generally cited by Westerners as the cause of the conflict). It’s how we arrived, three years after that, at a UN report which found that UNRWA schoolbooks funded by Western taxpayers called Jews “liars,” “cheats,” and “moneylenders” and used maps on which no country called Israel existed. And it’s how we arrived at 2001, after many of us hoped the conflict was about to be solved, when the official magazine of Fatah, the party of Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas, insisted that Israel accede to the “return” of refugees in order to “help Jews get rid of the racist Zionism that wants to impose their permanent isolation from the rest of the world.” It was around the same time, in 2001–2002, after no fewer than 87 suicide bomb attacks, that most Israelis, including supporters of the Oslo peace process like the authors, realized that we’d misunderstood what was going on. “Return” wasn’t an empty slogan or a negotiating tactic. The game was, tragically, zero-sum.

The War of Return is a valuable book, particularly now, as the United States emerges from the four strange years of the Trump administration and presumably returns to a foreign policy more closely resembling what came before. Many Israelis, focused on their own problems and with little idea of the domestic controversies engendered by the last president, appreciated his administration’s willingness to break with the calcified policies of the past—like the ahistorical obsession with settlements as the main cause of the conflict, or the idea that the Palestinians are key to a wider regional peace.

One of the Trump administration’s moves was to cut funding for UNRWA, moving in the direction of the authors’ practical proposals in the book’s final chapter. Funding for the Palestinians, Schwartz and Wilf suggest, should continue, but via the Palestinian Authority—not through the refugee agency whose goal, consciously or not, is to encourage the idea that Israel is temporary and “return” a possibility, maintaining the conflict in perpetuity. International money should be used in better ways to help the real people involved, the authors argue, and UNRWA should finally follow its contemporary, the Korean refugee agency of the 1950s, into obsolescence.

This suggestion is an eminently sensible one, one of many in this clear and timely book. As Biden administration officials begin to formulate their stance toward a Middle East that has changed dramatically since the Democrats were last in power, The War of Return should be among the first books on the reading list.

Suggested Reading

Chaim of Arabia: The First Arab-Zionist Alliance

Chaim Weizmann regarded his 1919 agreement with Emir Faisal as an epoch-making treaty. That didn’t turn out to be the case, but a century later an Arab-Zionist alliance may be reemerging.

Original Sins

John Judis book about Truman's Middle East policy isn't a rant, but it's not exactly history either.

One State?

Sari Nusseibeh's recent book is a new formulation of an old proposal.

Awe and Joy

S. Y. Agnon curated a stunning anthology of Jewish texts, published later in English as Days of Awe. In his introduction to the anthology, the eminent scholar Judah Goldin grappled with the idea of awe—and so does this author.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In