Chaim of Arabia: The First Arab-Zionist Alliance

On January 3, 1919, a few weeks after World War I ended, the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann met with Emir Faisal, the commander-in-chief of the Arab uprising against the Ottoman Empire, at a London hotel. Faisal’s father, King Hussein of Hedjaz, ruled the two holiest sites of Islam—Mecca and Medina—and the family traced its lineage to the prophet Muhammad. Faisal was accompanied to the meeting by his adviser, friend, and translator,

T. E. Lawrence, who had helped him lead the Arab Revolt.

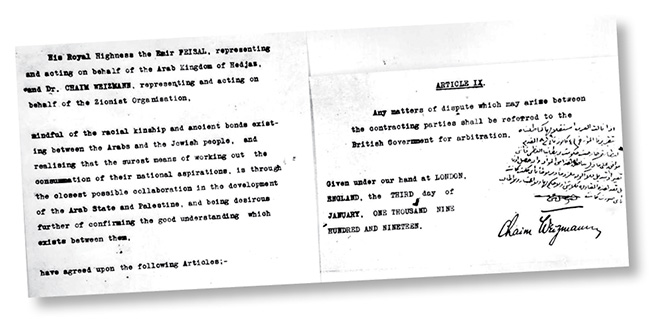

At the meeting, Weizmann and Faisal signed an agreement, brokered over the preceding month by Lawrence, exchanging Arab acceptance of the Balfour Declaration for Zionist support of an Arab state in the rest of the Ottoman lands. In February, they traveled to the Paris Peace Conference, where the victorious Allies would remap Europe and the Middle East, and made complementary presentations about the future of the region.

In the famous 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia, Lawrence would be played by Peter O’Toole, and Faisal by Alec Guinness. Weizmann was not portrayed at all, but perhaps he should have been. His arduous wartime trip, in June 1918, from Palestine to Faisal’s remote desert military camp—a five-day journey by train, boat, car, camel, and foot—led to their January agreement.

The Balfour Declaration, issued on November 2, 1917, had pledged support for a Jewish national home in Palestine, in part to generate support in America and Russia for Britain’s war effort. The British believed that both countries had influential Jewish populations and that the declaration would help keep Russia and America in the war against Germany and the Ottoman Turks. It was also, however, part of a broader British war strategy—one designed to bring the Jewish, Arab, and Armenian national movements into an informal alliance to defeat the Ottoman Empire.

Two weeks after the declaration, Sir Mark Sykes—the British diplomat who had negotiated the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 that divided the Middle East into British and French spheres of influence—outlined the British diplomatic strategy in a letter to the British War Cabinet secretary, Lt. Col. Sir Maurice Hankey:

We are pledged to Zionism, Armenian liberation, and Arabian independence. Zionism is the key to the lock. . . . If once the Turks see the Zionists are prepared to back the Entente and the two oppressed races [the Arabs and Armenians] … [the Turks] will come to us to negotiate.

To encourage this alliance, Sykes wrote, “our immediate policy should be by speech and open statement” to promote “Zionist, Armenian, and Arab common action and alliance.” A month after the Balfour Declaration had been issued, a celebration was held at the London Opera House, drawing a capacity crowd of more than 4,000, with thousands more turned away. Lord Robert Cecil, the British undersecretary of state for foreign affairs, addressed the gathering and said British policy was “Arabian countries should be for the Arabs, Armenia for the Armenians, Judea for the Jews.” Arab and Armenian representatives also attended the event and gave congratulatory speeches.

In the following months, Weizmann formed a Zionist commission to travel to Palestine to bring relief to the war-torn Jewish community, plan for new Jewish institutions (including the Hebrew University), and meet with Arab leaders. Upon arriving in April 1918, he learned that the anti-Semitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion had been widely distributed among the Arabs, leading to rampant speculation that—as he wrote caustically to Balfour from Tel Aviv—the British were “going to hand over the poor Arabs to the wealthy Jews, who are . . . ready to swoop down like vultures on an easy prey and to oust everybody from the land.”

Arab opposition, however, was not merely the result of propaganda or fear-mongering. Even prior to World War I, some Arab notables in Palestine had been alarmed by the growing Zionist presence in the land, and the formal British endorsement of a “national home for the Jewish people” there significantly deepened their concerns.

To counteract both old worries and new rumors, the British arranged for Weizmann to address Muslim and Christian leaders in Jerusalem at a dinner on April 27. Weizmann began by saying it was “with a sense of grave responsibility that I rise to speak on this momentous occasion. Here my forefathers stood 2,000 years ago.” The Jews were not coming to Palestine, he said, they were returning. Moreover, he continued, there was room in Palestine for many times the existing population. The Zionists endorsed the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans and sought only “the opportunity of free national development in Palestine, and in justice it cannot be refused.” As to the question of sovereignty in Palestine, Weizmann asserted that it should be deferred while the country developed, and it should be administered by a Great Power in the meantime.

Weizmann’s speech was consistent with the “organic” Zionism he espoused, which aimed for more than a cultural home but less than an immediate state. He wanted the right of Jewish immigration and the opportunity to build Jewish institutions in Palestine—which he believed would inevitably evolve into a democratic Jewish state. This was also consistent with what Lord Balfour had said a Jewish “national home” meant at the October 31, 1917, British cabinet meeting that approved the declaration. It would be

some form of British, American, or other protectorate, under which full facilities would be given to the Jews to work out their own salvation and to build up, by means of education, agriculture, and industry, a real centre of national culture and focus of national life. It did not necessarily involve the early establishment of an independent Jewish State, which was a matter for gradual development in accordance with the ordinary laws of political evolution.

Weizmann’s speech was well received that evening, and the British then arranged for him to travel to meet with Faisal next.

Turkish forces still occupied the Jordan Valley in the spring of 1918, so Weizmann could not travel directly from Jerusalem to Faisal’s camp on the Transjordanian plains. He had to travel to Tel Aviv, take a train to Suez, circumnavigate the Sinai Peninsula in a dilapidated cargo boat, proceed north 75 miles from Aqaba by car (which broke down), continue by camel, and then complete the journey on foot. The weather, he wrote his wife Vera, was “like standing near a red-hot oven.” It took him five days to travel from Tel Aviv to Faisal’s camp, where he watched Arab military movements through binoculars and then looked west across the Jordan River:

I looked down from Moab on the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea and the Judean hills beyond. . . . [A]s I stood there I suddenly had the feeling that three thousand years had vanished. . . . Here I was, on the identical ground, on the identical errand of my ancestors in the dawn of my people’s history . . . that they might return to their home.

The next morning, Weizmann and Faisal met for almost an hour, with a British military attaché, Lt. Col. P. C. Joyce, acting as their as interpreter. Weizmann explained Zionism’s goals in the same way he had in Jerusalem, and Joyce’s minutes state that Faisal repeatedly endorsed cooperation between Jews and Arabs. Faisal stipulated that only his father could make political commitments, but, according to Joyce’s minutes, he “personally accepted the possibility of future Jewish claims to territory in Palestine.” Joyce sent his minutes to Balfour, who asked him to convey to Weizmann “my appreciation of the tact and skill shown by him in arriving at a mutual understanding with the Sheikh.” Following the meeting, Faisal suggested that they take a photograph together.

After he returned to Tel Aviv, Weizmann wrote to Vera that he had found Faisal “quite intelligent,” a “very honest man,” interested in “Damascus and the whole of northern Syria” but—strikingly—“not interested in Palestine.” Weizmann later told a Zionist group that he considered the meeting “momentous.” Faisal and he had “fully understood each other.”

Faisal’s relative indifference to Palestine was understandable given his larger goals. At the time of the Balfour Declaration, Palestine was largely undeveloped and sparsely populated, with a total population of about 60,000 Jews and 600,000 Arabs, approximately 5 percent of the Arabs then living under Ottoman rule. Faisal was primarily interested in Arab sovereignty in—and the eventual unity of—the key cities of Damascus, Baghdad, Mecca, and Medina. In Jerusalem, the residents had been mostly Jewish since the late 19th century.

Faisal and his father believed Zionism would bring financial resources and technical expertise to Palestine, transforming the economic circumstances of the Arabs in both Palestine and beyond. In January 1918, D. G. Hogarth, director of Britain’s Arab Bureau in Cairo, had traveled to Jedda to deliver to King Hussein a formal message regarding British policy: The Arabs would be given “full opportunity of once again forming a nation,” and “no obstacle should be put in the way” of the return of the Jews to Palestine. All holy sites would be protected and the religious and political rights of all residents preserved. The message emphasized the importance of “the friendship of world Jewry” to the Arab cause. In an article published in March 1918 in Al-Qibla, the daily newspaper in Mecca, the king wrote that Palestine was “a sacred and beloved homeland” for “its original sons” [abna’ihi-l-asliyin], and the “return of these exiles [jaliya] to their homeland” would be beneficial to the region.

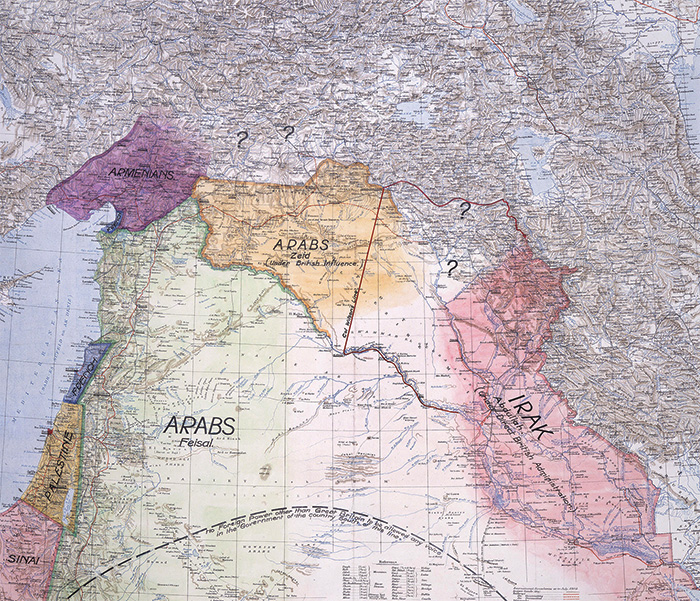

After World War I, Lawrence submitted a map to the British cabinet outlining his vision of the postwar Middle East. The map assigned a broad swath of land to Faisal; an additional area labelled “Irak” to Faisal’s older brother, Prince Abdullah; a northern area to Faisal’s younger brother, Prince Zeid; an area in the northwest to the Armenians; and a small “Palestine” comprised of the area west of the Jordan River and a narrow strip of land on the eastern bank. At the time of the Balfour Declaration, “Palestine” was considered to comprise not only the area west of the Jordan but an equally large area to the east, so Lawrence’s proposed delineation of “Palestine” effectively split it in half, assigning the Transjordanian portion to Faisal.

On December 10, 1918, Faisal arrived in London with Lawrence, and they met with Weizmann at the Carlton Hotel the next day. Weizmann wrote a long memorandum summarizing their discussion, noting that Faisal had promised that at the Paris Peace Conference—scheduled to begin in January—he would recognize the national and historical rights of Jews to Palestine and the appointment of Britain as trustee over it, with protection of the Muslim holy places and the economic interests of the Arabs there.

The next day, the Times of London carried a statement from Faisal, stating, “The two main branches of the Semitic family, Arabs and Jews . . . understand one another, and I hope that as a result of interchange of ideas at the Peace Conference . . . each nation will make definite progress towards the realization of its aspirations.” On December 27, he met with representatives of the British Foreign Office and told them he recognized the moral claims of the Zionists in Palestine. Two days later, at a banquet given in his honor by Lord Walter Rothschild, a prominent British Zionist, Faisal gave a speech (with Lawrence translating), declaring, “No true Arab can be suspicious or afraid of Jewish nationalism. . . . We are demanding Arab freedom and we would show ourselves unworthy of it, if we did not now, as I do, say to the Jews—welcome back home.”

The following month Faisal and Weizmann met again at the Carlton Hotel and signed their formal agreement, which explicitly recognized “the national aspirations” of both Jews and Arabs. The agreement provided that “all measures shall be adopted” to implement the Balfour Declaration, including “immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale,” while protecting the civil and religious rights of Arabs and providing for Muslim control of Muslim holy sites. The Zionist movement promised to support formation of an Arab state and provide economic, technical, and other assistance to it.

The agreement was silent on the ultimate political sovereignty over Palestine. At that point, Faisal would not have endorsed a Jewish state, and Weizmann would not have sought one, since the Jews were not yet a majority in Palestine. Weizmann envisioned a slow process, perhaps spanning decades, involving immigration and institution-building in preparation for a state. He viewed the Balfour Declaration not as an announcement of a state in Palestine but rather as a charter giving the Jews the right to build one there.

On the final page of the agreement, Faisal added a handwritten proviso, conditioning the entire agreement on the achievement of Arab independence as set forth in a memorandum he had delivered that week to the British Foreign Office. The proviso, written in Arabic, read:

Provided the Arabs obtain their independence as demanded in my memorandum [to the British] . . . I shall concur in the above articles. But if the slightest modification or departure were to be made, I shall not then be bound by a single word of the present agreement.

In his memorandum, Faisal wrote that the “aim of the Arab nationalist movements” was to “unite the Arabs eventually into one nation” but not to seek a single state immediately, since—in Faisal’s words—it was “impossible to constrain” all the provinces into “one frame of government,” given their economic and social differences. He asserted that Syria was “sufficiently advanced politically to manage her own internal affairs” and was thus entitled to immediate freedom, while Hedjaz would continue as an independent kingdom and should be allowed to work out its relationship with neighboring Arab areas on its own.

Faisal dealt with Palestine in a separate paragraph, which did not claim Arab sovereignty. The memorandum stated that “the Arabs cannot risk assuming the responsibility of holding level the scales in the clash of races and religions that have, in this one province, so often involved the world in difficulties.” Faisal sought instead an “effective super-position of a great trustee,” together with “a representative local administration” to promote “the material prosperity of the country.” This was consistent with Weizmann’s position.

Subsequently, at the Paris Peace Conference, Faisal excluded Palestine from his demand for Arab independence, asking instead that, because of its “universal character,” Palestine be “left on one side for the mutual consideration of all parties interested.” The Zionist submission to the conference specified boundaries for the Jewish national home leaving almost all of Transjordan to the Arabs, consistent with Lawrence’s November 1918 map.

In March 1919, the New York Times, in a news story headlined “Prince of Hedjaz Welcomes Zionists,” published the text of a letter Faisal delivered to Felix Frankfurter designed to ensure continued Zionist support for Arab nationalism after he had given an interview to Le Matin, a Parisian daily, that cast doubt on his acceptance of the Zionist goals. The letter stated that, “Our deputation here in Paris is fully acquainted with the proposals submitted by the Zionist Organization to the Peace Conference, and we regard them as moderate and proper. . . . [Dr. Weizmann and I] are working together for a reformed and revived Near East.”

The conference, however, did not award Faisal the independent Syrian state he sought. Instead, it endorsed a mandate system giving France control of Syria, from which the French expelled Faisal by force the following year. The conference endorsed British mandates over Palestine and Iraq, and Britain installed Faisal as king of Iraq and his brother Abdullah as king of Transjordan. Hedjaz eventually became part of Saudi Arabia. But Faisal’s handwritten condition in his agreement with Weizmann had not been met by the Allies, and he departed the conference with a sense of betrayal. In July 1919, the Syrian Congress, comprising representatives of prominent Arab families in Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, adopted a resolution that rejected French rights to any part of Syria, claimed Lebanon and Palestine as inseparable parts of Syria, and opposed Jewish immigration.

Lawrence was also deeply disappointed. During the Paris Peace Conference, he began drafting Seven Pillars of Wisdom, his famous account of the “procession of Arab freedom from Mecca to Damascus.” Even in the extreme desert heat, he wrote, “the morning freshness of the world-to-be intoxicated us.” But after the war, “the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew. . . . we had worked for a new heaven and a new earth, and they thanked us kindly and made their peace.” Weizmann considered him a friend, with a sympathetic understanding of Jewish aspirations in Palestine.

Eventually, most of the Ottoman Empire was transformed into independent Arab states with a total area of approximately 1,184,000 square miles. Britain was given a United Nations mandate in 1922 to implement the Balfour Declaration in a Palestine covering less than 11,000 square miles. Britain increasingly retreated from that obligation until, with its 1939 White Paper, it reneged on it entirely and proceeded to block any further significant Jewish immigration to Palestine or further purchases of land. After World War II, Britain returned its mandate to the United Nations, unfulfilled.

Faisal died in 1933 at the age of 50, having used his diplomatic skills over more than a decade to build Iraq into a fully independent state. His biographer, the Iraqi scholar Ali A. Allawi, writes that “realistic, purposeful and constructive patriotism also died with Faisal, to be replaced with the far more strident, volatile and angry nationalism that swept the Arab world after the end of the Second World War.” For Weizmann, his agreement with Faisal (which he often called a treaty) was a landmark of Arab-Jewish relations. In 1936, in testimony before the British Peel Commission on Palestine, he recounted its origins:

[I]n 1918 there was one distinguished Arab who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Arab armies which were supporting the right flank of Allenby’s army, the then Emir [Prince] Faisal—subsequently King Faisal—and on the suggestion of General Allenby I went to his camp. I frankly put to him our aspirations, our hopes, our desires, our intentions, and I can only say—if any oath of mine could convince my Arab opponents—we found ourselves in full agreement, and this first meeting was the beginning of a lifelong friendship, and our relationship was expressed subsequently in a treaty.

In 1946, when the British again considered the future of Palestine, Weizmann wrote to Prime Minister Clement Attlee, arguing that Jewish and Arab national aspirations were compatible:

The Balfour Declaration was part of a general Middle Eastern settlement, offering a subcontinent to the Arabs and a “small notch”—as Lord Balfour put it—to the Jews. In 1917, it was the protagonists of the Arab revival—Sir Mark Sykes and Colonel T. E. Lawrence—who were among the foremost advocates of the Zionist settlement in Palestine. King Faisal was agreeable to a Jewish Palestine because he realized that it would promote the general progress of the Arab world. I submit that the policy supported by these three outstanding figures—of a Jewish Palestine within a revived Arab Middle East—is still capable of successful implementation.

On October 18, 1947, Weizmann addressed the United Nations as it approached a vote on a two-state resolution for Palestine. He noted the Arab achievement of independent states in a wide area of the Middle East and then said:

There was a time when Arab statesmanship was able to see this equity in its true proportions. That was when the eminent leader and liberator of the Arabs, the Emir Faisal, later King of Iraq, made a treaty with me declaring that if the rest of Arab Asia were free, the Arabs would concede the Jewish right freely to settle and develop in Palestine, which would exist side by side with the Arab states.

Weizmann acknowledged that Faisal’s condition had not been satisfied in 1919. But, he told the UN, “[t]he condition which [Faisal] then stipulated, the independence of all Arab territories outside Palestine, has now been fulfilled.”

Two weeks before the United Nations voted on its resolution, Weizmann discussed the issue in the UN Delegates Lounge with Eleanor Roosevelt, FDR’s widow, who was a member of the U.S. delegation. The next day, he wrote her to say he was sending documents, including “my treaty” with Faisal, Faisal’s letter to Frankfurter, and Faisal’s formal statement to the Paris Peace Conference, in order to “dispel the impression which is so assiduously circulated by the Arabs that it was all done without the consent of the Arabs at that time.”

On May 16, 1948, Weizmann—as of that day the provisional government’s president—sent a message to a Madison Square Garden rally celebrating Israel’s May 14 declaration of independence—to which all five neighboring Arab states had responded by invading Israel. He recalled, yet again, his “treaty” with Faisal and promised that the Arab nations would find “the Jewish State always ready and eager to enter into neighborly relations and to join with them in a common effort to increase the welfare and prosperity of the Near East.”

The Weizmann-Faisal agreement marked a historic moment, a time when Arabs and Zionists coordinated their diplomatic efforts to realize their respective national goals. One hundred years later—with their states in existence but facing existential threats from Iran—another de facto alliance between Arabs and Jews has emerged, composed of Israel, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt, to oppose the new would-be hegemon. Such an alliance is not quite the unprecedented event many believe it is. Indeed, it might be called the second Arab-Zionist alliance.

Suggested Reading

100 Years of Solicitude: Commemorating Balfour

The controversies over how (and whether) Great Britain should celebrate the recent centenary of the Balfour Declaration were revealing. Anglo-Israel relations have rarely been uncomplicated, but they could soon be much worse.

A Mechitza, the Mufti, and the Beginnings of the Arab-Israeli Conflict

In his new book, Hillel Cohen offers an analysis of the Arab-Jewish violence of 1929 that goes very much against the grain of the usual Zionist narrative and even the non-partisan historical research concerning this period.

In Praise of Humility

There are those who carry the quest for yichus to extremes; Steven Weitzman is not among them.

Friends of Zion

Getting by with a little help from our friends.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In