Blocked Desire

One of the hallmarks of A. B. Yehoshua’s career is that he has kept trying new things. Sometimes this has involved formal experiments, the most salient of these being Mr. Mani (1990), a historical novel constructed through dialogues in which the words of only one of the two interlocutors are given, structured in a chronological sequence that begins in the 1980s and, moving backward, concludes in the 1840s. More often, Yehoshua has hewn to the style and narrative mode he first developed in his second book, Facing the Forests (1968)—a kind of deadpan, understated Hebrew, in a narrative where the main character incrementally edges into bizarre or emotionally disturbed actions.

The Tunnel, Yehoshua’s most recent novel, written as he moved into his eighties, does not exhibit any traits of what some literary critics have called “the style of old age”—though definitions vary, this usually involves a pointedly pared down kind of writing, resisting literary ornamentation—but its unusual subject, incipient dementia, is patently a concern of old age. It is not a condition from which Yehoshua himself suffers (fortunately, he is still perfectly lucid and lively as a writer), but, like most of us who have reached the ninth decade, it is surely something that has afflicted some of his contemporaries. However, he has experienced other infirmities of aging—the hearing problem he assigns to the protagonist of his novel Retrospective (2011) is his as well.

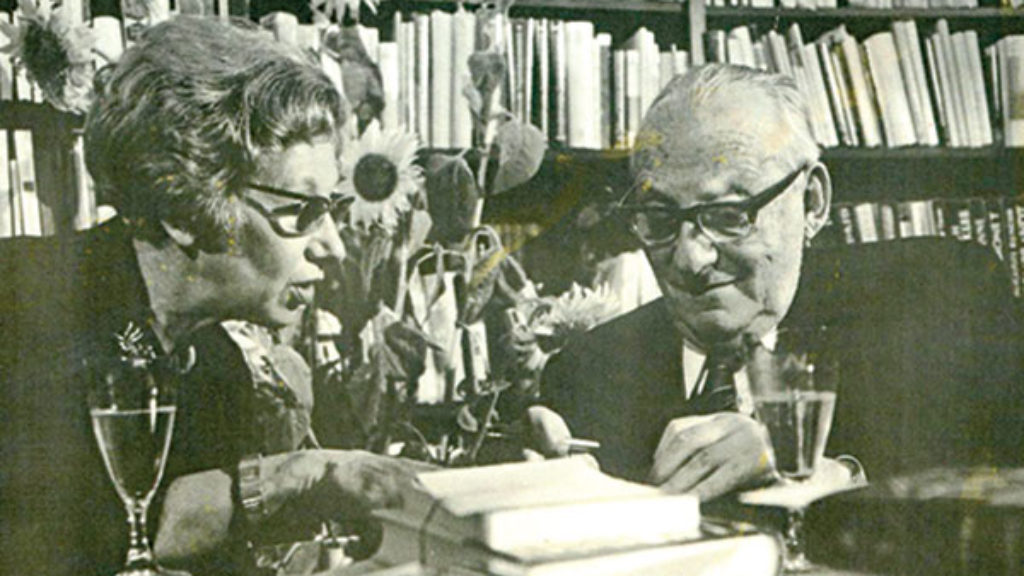

On the very first page of The Tunnel, the central figure, Zvi Luria, a retired road engineer in his seventies, is shown a scan of his brain by his neurologist. There is an ominous dark spot on the cerebral cortex that, he is told, will eventually grow larger and trigger cognitive loss, especially in regard to memory. Luria immediately, and understandably so, becomes obsessed with this menace to his mind, and his decline will become more pronounced in the course of the novel. He has the staunch moral support of his wife Dinah, a prominent pediatrician, who is with him in the doctor’s office and remains by his side, literally and figuratively, through much of what follows. Their long marriage is notable for its unwavering and passionate intimacy. Most Israeli readers have recognized that the character of Dinah is largely based on Yehoshua’s wife Ika, to whom he was extremely close and who died while he was writing this book. Yehoshua lovingly dedicated the novel to her memory, and Dinah is a kind of tribute to his cherished Ika.

However, the support and concern that Dinah constantly offers her husband are not always easy for him to tolerate because, haunted by the fear of decline, he is often irritable and resents what he sometimes regards as her interference. The neurologist had suggested that it might help for him to remain intellectually active, and Dinah, picking up the cue, contrives to enlist Luria as an unpaid assistant to an engineer named Maimoni, who now works in Luria’s old office. At the instance of the army, Maimoni is planning a road in the Negev. There is a hill in the way, on top of which an anomalous Palestinian family of three—a father with his grown daughter and son—have taken refuge for reasons at first obscure. Troubled by the prospect of displacing them, Luria insists that instead of demolishing the hill, the road builders must tunnel through it, and he sets about drawing up plans for the tunnel.

A story centered on cognitive decay and involving an encounter with Palestinians that has fraught political implications may sound a little grim, but it is characteristic of Yehoshua’s fiction that most of this is rendered as wry comedy—a strange sort of comedy that repeatedly highlights bizarre incongruities. When, for example, Luria, headed home from the neurologist, turns on the ignition of his little red car, he hears “a brief, soft murmur amid the gargle of gears and pistons, the voice of a Japanese or Korean girl, possibly planted in the electrical system to wish the discriminating driver a safe trip in his new car.” Stuart Schoffman’s translation throughout is apt, though he permits himself a bit of editing; in this case, he revises the droll conclusion of the sentence, which in the Hebrew says “the driver who chose the right car.” Later in the book, the Asian girl in the engine will reappear as “the whispering geisha.”

Luria’s consciousness is reflexively, unintentionally whimsical. This drollness is often at play in Luria’s thoughts about both his illness and the doctor’s advice. The neurologist had told him that preserving an element of passion in his marriage might mitigate his condition. When at one point the couple comes home to a darkened apartment and Dinah is about to turn on the light, Luria stops her, thinking, “No, he won’t let the light dampen the desire he owes to himself and his neurologist.” Whimsy is especially evident in the many similes that occur to Luria. When, on an unannounced visit to a colleague’s wife, she jumps out of bed to greet him stark naked, then quickly wraps herself in a sheet, he thinks she looks “like a barefoot mummy.” Trying to drive home at night, he runs into a traffic jam because a bulldozer has fallen off a flatbed truck, crushing two cars, “and now in the moonlight it waves its toothy shovel at the sky like the trunk of a yellow elephant turned on its back.”

Sexual desire, which ranges from happy marital consummation to free-floating lust, plays an important role in Luria’s story. It is an impulse we conventionally associate with youth, but this septuagenarian has it in abundance, if ambivalently. That alluring naked woman transmogrified into a mummy angrily confronts him years after the encounter and tells him, “you lusted after me.” When he responds that if it was lust, he “blocked” it, she asks, “Who asked you to block it?” The phenomenon of blocked lust is a familiar theme in Yehoshua, and it is especially important here in Luria’s relation to the beautiful daughter of the Palestinian family on the Negev hilltop.

The father of the family had been a school teacher in a West Bank village. His wife, suffering from a grave cardiac condition, needed a heart transplant, which was possible only in Israel. In order to afford the procedure, the teacher sold a plot of land in the village using old Ottoman documents for the property that would prove to be invalid. Meanwhile, with no heart available for the transplant, his wife died, and the sale infuriated his fellow villagers. Without documents, he fled across the border into Israel with his son and daughter, who took on the names Ofer and Ayala, both of which mean “deer” (as does the name Zvi). When Luria first meets these undocumented, Hebrew-speaking Palestinians, he asks them, puzzled, “Excuse me, what are you? Jews or not?” The lovely Ayala responds:

“Jews? What for?”

“So you’re Palestinians?” concludes Luria.

“We were,” she answers sadly, “we once were, but no longer.”

“So now, what are you? Just Israelis?”

“Not yet, but maybe we will be, maybe . . .”

When the young woman no longer knows how to respond to these questions about their identity, her father intervenes, “Meanwhile, sir, we are Nabateans, we have gone back to being Nabateans.” It turns out that the hill on which they are encamped was once inhabited by Nabateans, an ancient people of the region neither Jewish nor Arab, famous for the city of Petra in Jordan they hewed out of red sandstone. The idea that this family is now Nabatean is, of course, a little crazy, but it aligns with still another aspect of shifting identity introduced by Yehoshua: the notion that the Arabs of Palestine once were Jews, converted in the Islamic conquest, and could theoretically revert to being Jews. At least according to Luria, it is an idea that was entertained by Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. Faithful readers of Yehoshua may recall that the chronologically first of the titular Mr. Manis, losing his grip on sanity, goes wandering through the dangerous streets of Jerusalem’s Old City in search of the hidden Jews within the Arabs. Yehoshua appears to regard this idea as a seductive fantasy, which, if only it were true, might be the basis for resolving the conflict between the two peoples.

The political implications of the Palestinians on the hilltop are spelled out in another way. Luria wants to build a tunnel for the road in order to avoid displacing the Palestinian family, so their predicament becomes a microcosmic image of a dark chapter in Zionist history. The purpose of the road, moreover, is not just a matter of urban planning. Though its purpose is withheld from Maimoni and his aged assistant, they speculate that it is intended to lead to a military base or listening post that could be important in the next war. Displacing people for military ends has ominous political ramifications. However, the connection of this to the primary theme of Luria’s dementia is never made clear.

Somewhat clearer is the theme of sexual desire, whose fading is generally an element of old age. Luria’s fidelity to his wife is never in question, as we saw in his resistance to the invitation of the momentarily naked woman who then wraps herself like a mummy. Extraordinarily, Luria at one point blandly asserts, quite fantastically, that his dementia began when he blocked the desire sparked by the unclothed appearance of his colleague’s wife. This detail, too, harks back to one of Yehoshua’s earlier works. In his short story “A Long Hot Day, his Despair, his Wife and his Daughter” (1968), the protagonist, also an engineer, is working in Africa. During his time there, he views a nighttime native ritual, and when one of the young women dancing in it, naked from the waist up, lands herself in his lap, he freezes. This moment of blocked desire seems to be the origin of the psychological paralysis that overtakes him on his return to Israel—he can do little more than lie in bed most of the day brooding over his adolescent daughter’s sexual awakening. Yehoshua’s fiction is populated by figures who toy with fantasies that appear to become facts against the grain of scientific explanation, just as this novel begins with the ineluctable medical determination of the dark spot on the cerebral cortex showing in the scan, something that surely has nothing to do with the suppression of desire.

In any case, though Luria is a devoted and faithful husband, he does feel intermittent flickers of wandering desire. It is roused in him by the erotically magnetic Ayala. Luria, true to marital form, never contemplates acting on this desire, though he does play with still another fantasy—why not have a second wife, this young one adding to the older one? (This, too, recalls an earlier Yehoshua novel. In Journey to the End of the Millennium, published in 1997, the Sephardi protagonist arrives from North Africa in 10th-century France accompanied by his two wives, one old and the other young, in order to demonstrate to his nephew’s pious Ashkenazi spouse that polygamy really works.)

The concluding pages of the novel introduce a last twist of grotesque comedy. Luria has been progressively forgetting everything: his cellphone, the ignition code for his car, which street his apartment building is on. At the end of the book, he can no longer remember his own name. During a final visit to the Nabatean hilltop, he runs into the Palestinian schoolteacher, who greets him as Zvi. “Luria accepts the return of his name with excitement and gratitude,” as though he had been given back a lost watch or wallet. But, oddly, he is also “filled with fear.” Is it fear that he will lose his name again with no one to give it back to him, or, perhaps more darkly, fear of the identity that goes along with the name? At this moment, the teacher spots a deer, a real zvi, and points it out to Luria. The Palestinian then performs an act rich in ambiguity, which I will not reveal, that leaves the reader wondering about the meaning of Yehoshua’s novel.

The Tunnel, as I have tried to indicate, is something of a hodgepodge. Its different pieces may not fit together as tightly as one would like, but each piece has its own fascination. In any case, the main achievement of the book is to draw us into the process of mental deterioration through aging and the gnawing anxieties about decline triggered by that process, a subject rarely tackled by novelists. This may sound dire, but Yehoshua’s distinctive gift as a novelist is demonstrated yet again in his ability to turn it into an occasion for absurd comedy as well as for fear.

Suggested Reading

Spanish Charity

The sight of a secular Israeli artist in a cathedral confessional in Spain is one of the more interesting moments in recent Israeli fiction. A new novel by A.B. Yehoshua.

Love and War

David Grossman has for sometime been one of Israel's most talented and important writers. In many of his novels, his feeling for adolescence—one is tempted to say, his identification with it—has been so brilliantly intuitive that the imagining of adulthood has scarcely been possible. In To the End of the Land, Grossman makes his breakthrough.

Lost from the Start: Kafka on Spinoza Street

Jerusalem-based writer Benjamin Balint has crafted a wise and eloquent study of Kafka around the eight-year battle in Israeli courts over Max Brod’s literary estate.

Yehuda Amichai: At Play in the Fields of Verse

Yehuda Amichai was an exuberant person with a lively, impish sense of humor. He was, at the same time, a melancholy man. Both traits are present in his poetry.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In