Lost from the Start: Kafka on Spinoza Street

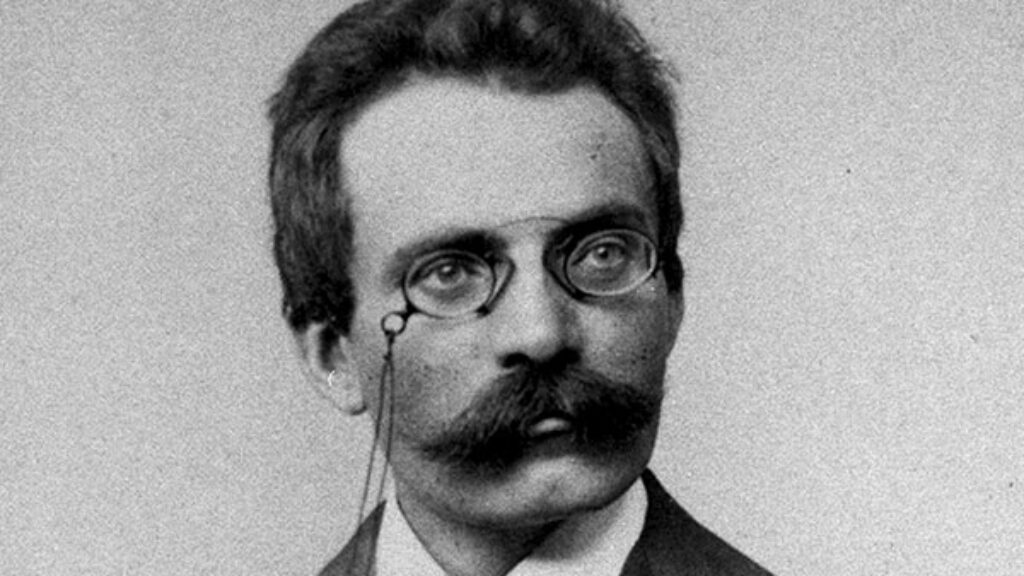

If one had a dime for every time the adjective “Kafkaesque” has been used in print, one could have bought the original manuscript of The Trial from Esther Hoffe of Tel Aviv, secretary and heir to the childless Max Brod. Well, maybe not quite: She got $1.98 million for it from a rare book dealer representing the German Literature Archive in Marbach, Germany 20 years after Brod’s death. Kafka fan Philip Roth, reacting to the 1988 sale in a letter to the New York Times, bemoaned the “lurid Kafkaesque irony” of selling the manuscript to the country that killed Kafka’s three sisters and would have murdered him too, had he not died of tuberculosis in 1924, a month shy of his 41st birthday.

Now, 30 years later, the Jerusalem-based writer Benjamin Balint has crafted a wise and eloquent study of Kafka around the eight-year battle in Israeli courts over Brod’s literary estate. Following Esther Hoffe’s death in 2007, Brod’s papers, including Kafka manuscripts and notebooks that Brod had spirited from Nazi-occupied Prague to Palestine in 1939, landed in the hands of her two daughters. Over the years, many other Kafka papers had made their way to Marbach or the Bodleian Library at Oxford. The literary treasures that remained in Tel Aviv were stored in safety-deposit boxes or in the apartment on Spinoza Street that the unmarried Eva, a longtime employee of El Al, shared with many cats. (Her sister, Ruth Wiesler, died in 2012.)

The case began in family court in Tel Aviv, when the sisters sought to probate Esther’s will, continued on in District Court, and culminated in the Supreme Court. The contest turned on the issue of national rights versus property rights. The lawyers for Israel’s National Library claimed that since Franz Kafka is a Jewish national asset, his papers should belong to the Jewish State, and that this would fulfill Brod’s wishes that they be turned over to a public archive. Eva’s advocates argued that she had inherited the estate Brod bequeathed to her mother and could do with the papers as she wished. In particular, she could sell them to the Marbach archive, whose attorneys were also on hand. The lawyers, writes Balint, “fluctuated between two rhetorical registers, the legal and the symbolic.” He does the same, alternating between a chronicle of the “last trial” and a literary history of Kafka: his telenovela life, the reception of his work in Israel and Germany, and his deep involvement with Max Brod, which lasted long after Kafka’s death. The book is a felicitous mixture of reportage and scholarship, and can serve as a splendid gateway into Kafka for readers who may not have gotten through The Trial in college.

Balint artfully makes Eva Hoffe, with all her cat-lady histrionics, into a sympathetic protagonist, a surrogate for Kafka’s bewildered Josef K. Supreme Court Justice Elyakim Rubinstein, a former Israeli attorney general, rejects a key argument of Hoffe’s lawyer with “a schoolmaster’s manner, and with an air of omnicompetence about him.” Eva tells Balint, as she awaits the verdict: “As far as I’m concerned, the words justice and fairness have been erased from the lexicon.” Throughout the convoluted, exhaustively detailed legal saga, the author pays even-handed respect to opposing points of view, but we can tell which side he’s on. In Chapter One, “The Last Appeal,” he quotes from the novel: “A trial like this is always lost from the start.”

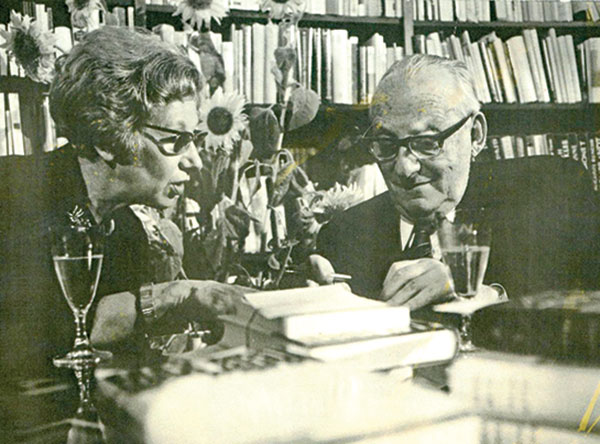

Max Brod, a hyperproductive writer (80 books or so), worshipped his tall, skinny, and vastly more talented friend and famously disobeyed Kafka’s instructions to burn all his manuscripts after his death, publishing them feverishly while editing them as he saw fit. The world thus owes the disloyal Max Brod an eternal debt. In 1937, Brod came out with a schmaltzy biography of Kafka, painting him as a saintly prophet of Zionism. Walter Benjamin dismissed the book in a long letter of 1938 to his own best friend, Gershom Scholem. Kafka’s friendship with Brod, he wrote, “is above all a question mark . . . I think I am on the track of the truth when I say: Kafka as Laurel felt the onerous obligation to seek out his own Hardy.” Among Balint’s many virtues as a writer is a keen ear for the great quote.

Brod was a ladies’ man; Kafka famously feared women, lived with his parents, and never married. The Nobel laureate Elias Canetti, in a fascinating little book of 1969 entitled Kafka’s Other Trial, endeavored to find the roots of The Trial in Kafka’s voluminous correspondence with his fiancée Felice Bauer of Berlin, whom he first met in Prague through Brod in 1912. Over five years and two broken engagements, they barely saw each other, but he wrote to her obsessively. In his very first letter to Felice, he confirmed their promise to travel together to Palestine. Some Kafkologists have interpreted this pledge as evidence of Zionism, others as mere flirtation. In 1913, he attended the 11th Zionist Congress, in Vienna, and wrote her that he sat there “as if it were an event totally alien to me.” The following year, he confided in a letter to Felice’s friend Grete Bloch: “I admire Zionism and am nauseated by it.”

Indeed in his diary, notes Balint, “Kafka mocked Palästinafahrer, or those who journeyed to Palestine, who ‘constantly mouthed about emulating the Maccabees.’” But he did learn Hebrew and even tried reading a novel by Y. H. Brenner. Near the end of his life he and his 19-year-old girlfriend Dora Diamant, daughter of a Hasid, fantasized about moving to Tel Aviv together and opening a restaurant. “But the dream of Zion would remain a dream unfulfilled,” says Balint. “Kafka allowed himself to imagine moving to Palestine only when his illness was so far advanced as to make the move impossible.”

To each his own Kafka. Canetti reads him as “the greatest expert on power,” whose fixation on small animals makes him “the only writer of the Western world who is essentially Chinese.” Be that as it may, Canetti also provides a tasty anecdote about the time Kafka went spazieren in Marienbad with the Belzer Rebbe. The Prague-born historian Saul Friedländer, in Franz Kafka: The Poet of Shame and Guilt, floats the notion of Kafka as a repressed homosexual (Orson Welles’s thrilling 1962 film of The Trial, starring Anthony Perkins, implies likewise). Balint has ably synthesized scores of sources in three languages, ranging from an item by Kafka’s gay Hasidic friend Jiri Langer (“Mashehu al Kafka,” 1941); to Martin Buber’s Drei Reden über das Judentum (1916, based on lectures attended in Prague by Kafka, who was underwhelmed); to Cynthia Ozick, Judith Butler, and the German scholar Reiner Stach, whose monumental three-volume biography has lately appeared in a superb English translation by Shelley Frisch. Oddly, the first part came out last, as Stach waited for the Spinoza Street stash, which contained valuable information about Kafka’s early years, to be made public (it also contained intimate letters between Esther and Max, reason enough for Eva’s ferocious opposition).

Stach has also published a charming book of outtakes called Is That Kafka? 99 Finds, which reminds us that Kafka was an ardent swimmer, frequenter of brothels, and proponent of natural medicine. Stach’s curiosities include Kafka’s outline for the ideal polity of a kibbutz and a facsimile of a letter Kafka penned in Hebrew to his teacher Puah Ben-Tovim.

It’s all fascinating stuff, but the big legal and cultural question remains: Who owns Kafka? Is he a Jewish writer or a German one? Balint’s book ends with a famous quote from a letter to Felice: “Am I a circus rider on two horses? Alas, I am no rider, but lie prostrate on the ground.” In January 1914, Kafka wrote an immortal line in his diary: “What have I in common with Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself.” Combing through his letters and diaries, scholars have found countless references to things Jewish. He became fascinated by Yiddish theater, to his assimilationist father’s consternation, and owned M. Y. Berdichevsky’s anthology of Jewish folklore. Gershom Scholem, Robert Alter, and others have detected kabbalistic, biblical, or talmudic overtones in Kafka’s writings. “Kafka’s world is the world of revelation,” Scholem wrote to Walter Benjamin in 1934. “The key to Kafka’s work,” he clarified, is “the nonfulfillability of what has been revealed.” Forty years later, in a lecture to the Bavarian Academy of Arts entitled “My Way to Kabbalah,” Scholem said there were only three books he “read and reread with true attentiveness”: the Hebrew Bible, the Zohar, and the collected works of Kafka.

Philip Roth, in a dazzling piece from 1973 called “‘I Always Wanted You to Admire My Fasting’; or, Looking at Kafka,” wrote of Kafka’s “oedipal timidity, perfectionist madness, and insatiable longings for solitude and spiritual purity.” Then he went on to imagine him in 1942 as a refugee in Newark, the Hebrew-school teacher of the nine-year-old Roth. Dr. Kafka (he did hold a law degree) begins dating Roth’s Aunt Rhoda, which ends badly, of course. (In homage to Roth, Nicole Krauss, in her recent novel Forest Dark, ruminates on Kafka as a refugee in Palestine, living in obscurity as a gardener on a kibbutz.) And yet, as Balint writes, “in all of Kafka’s fiction, there is no direct reference to Judaism. One searches in vain for Jews, or Jewish patterns of speech, in Kafka’s placeless fiction . . . Kafka rigorously strips his characters of discernable ethnic identities.”

There is one exception, which Balint mentions in an endnote: a “fragmentary story” written in 1922 and published by Brod in 1937 as “In Our Synagogue,” about “a timorous animal who takes up residence in a synagogue.” In A. B. Yehoshua’s novel Chesed Sefaradi (The Retrospective, 2013) an Israeli film director named Yair Moses discusses an early film of his, based on that story, at a festival in his honor in Spain. (As in The Trial, there is a pivotal scene in a cathedral.) Kafka was an early and enduring influence on Yehoshua. In the words of the fictional Yair Moses: “But as opposed to those who interpret every line of his writings in light of his private life and sexual struggles, and celebrate every Jewish detail exhumed from his biography, there were many readers, myself among them, for whom Kafka’s cryptic, radiant works transcended the specifics of his personality and inhabited the realm of the universal.” W. H. Auden, in a 1941 essay on Kafka called “The Wandering Jew,” also cast Kafka in a universal role: “Had one to name the artist who comes nearest to bearing the same kind of relation to our age that Dante, Shakespeare, and Goethe bore to theirs, Kafka is the first one would think of.”

The point, in the end, is not how Jewish Kafka was or wasn’t, but something much deeper: Is Israel a sovereign state of its citizens or the country of all Jews? “Throughout the trial,” writes Balint, “Israel acted as though it can lay claim to any pre-state Jewish cultural artifact, as though everything Jewish finds its culmination in the Jewish state, as though Jewish culture has been driven by a teleological thrust toward Jerusalem.” The irony is that Israel had never shown much interest in Kafka. “During the trial, the Marbach archive subtly portrayed Israel as a latecomer to the Kafka industry,” Balint writes. No Israel city has a street named for Kafka. There is no Hebrew edition of his complete works, whereas a Serbo-Croatian version came out in 1978. His three novels were translated into English in the 1920s, into Hebrew only much later, The Castle not until 1967. The critical edition of Kafka’s complete works in German, produced by an international team of scholars, was completed in 2004. The National Library in Jerusalem—“as of this writing,” Balint is careful to specify—does not own a copy.

How can this be? The author considers the possibilities: an Israeli aversion to the weak, passive galut Jew personified by Kafka, coupled with a persistent antipathy toward all things German, not least the language in which the annihilation of the Jews was carried out. Balint himself is inclined otherwise: He clearly relishes the sound and logic of German and often goes out of his way to deploy such confections as kulturkämpferischen Gestus (“gesture of culture-war”), Sprachunrichtigkeiten (Brod’s label for Kafka’s “linguistic errors”), and Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past). The efforts by Germany to claim Kafka, a Czech Jew, as one of their own served an important historical purpose, writes Balint:

Perhaps there was a recognition that to bring Kafka—precisely as a Jewish guardian of German prose, and as a Jew who died before he could fall victim to the Nazis—back into the German fold would be to erase the moral stain of the past, to regain a forfeited standing, and to recover a German language not yet defiled by the nihilistic bellowing of Hitler and Goebbels. Herein hides another irony with which the story of Kafka’s last trial is salted: the attempt to use the writer who raised self-condemnation into art as a means of self-exculpation.

Then again, Balint notes, the same has been said of Israel:

Judith Butler of Berkeley suggests that Israel, a small and insecure country, wishes to recruit Kafka for its increasingly urgent fight against cultural delegitimation. “An asset,” she says, “is something that enhances Israel’s world reputation, which many would allow is in need of repair: the wager is that the world reputation of Kafka will become the world reputation of Israel.”

In August 2016, the Supreme Court ruled against Eva Hoffe, ordering her to hand over the Brod estate to the National Library of Israel, for which she would receive no compensation. Justice Rubinstein, quoting the talmudic tractate Gittin, concluded that this had been the wish of Max Brod and must be obeyed. “Like the man from the country in Kafka’s parable ‘Before the Law,’” writes Balint, “Eva Hoffe remained stranded and confounded outside the door of the law.” Eva Hoffe died on August 4, 2018.

What is one to make of all this? “If the Israeli judges can be understood as the latest of Kafka’s gatekeepers of interpretation,” writes Balint, “then their verdict might be read as another telling reading—or misreading; as the latest page in the long history of the uses and abuses of Kafka’s literary afterlife at the hands of those who claim to be his heirs.” Fair enough, but let us give the final words to Kafka, who wrote in The Trial, with tantalizing obscurity: “The commentators tell us: the correct understanding of a matter and misunderstanding the matter are not mutually exclusive.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Discrimination and Identity in London: The Jewish Free School Case

How Britain's highest court misunderstands Judaism.

Thoroughly Modern Maimonides?: A Rejoinder

To sharpen Stern’s point, we may say that the person who believes God literally gets angry metaphorically angers God.

Return without Returning

In Micah Goodman’s new book, The Wondering Jew, he argues that Israeli Jews should develop a relationship with Jewish tradition that falls somewhere between strict adherence and total abandonment.

The Most Important Word in the World

For a moment, a literary giant and talmudic genius sparred over the implications of a biblical phrase.

Daniel Winter

Judith Butler is small and insecure. No wonder s/he projects the Kafkaesque facets of h/is/er identity onto the modern nation state that has been leaving the ghetto Jew behind since at least the election of Menachem Begin.