My Father and Birnbaum’s Heavenly City

In the autumn of 1936, a year and a half before Hitler’s troops moved into Austria, a remarkable monograph of fifty pages was published in Vienna. The work was remarkable both for its author and for its subject. Count Arthur Polzer-Hoditz was a prominent and influential member of the old Austrian Catholic aristocracy. He served with distinction in several ministries as well as in the Parliament, and as director of the cabinet he was the principal private secretary or chief of staff of Kaiser Karl, the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The subject of Polzer-Hoditz’s essay was Uriel Birnbaum, the youngest son of the foremost leader of pan-Herzlian Zionism, and, in fact, coiner of the terms Zionism and Zionist, Dr. Natan Birnbaum. After playing a major role in the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Natan gradually moved away from Herzl and devoted his considerable energies to Jewish cultural autonomy and diaspora nationalism, with a significant detour into Yiddishism. In the final phase of his checkered career he committed himself to strictly Orthodox observance and became a leading figure in the anti-Zionist Agudah Movement. The monograph was entitled simply: Uriel Birnbaum: Dichter, Maler, Denker (Poet, Painter, Thinker).

My father Leo Taubes recited these words about two years ago at a Friday night dinner, gazing straight ahead of him as if reading a paper, grinning somewhat guiltily. I had been begging him for years to share what he had been sporadically working on for so long, and now it was clear that, at least in his head, he had already composed an entire article. He never published it, though, and I found these lines, along with a few more pages, among his papers after he died. His familiar scrawl, difficult to decipher in the best of times, was even fainter and harder to make out. The truth is that even had my father been able to complete the piece, I doubt that he would have submitted it anywhere. In the more than 40 years that he was a professor of English literature at Yeshiva University, although he was always busy with a writing project, usually an original English translation—Moliere’s plays from the French, his own father’s volume of Yiddish limericks, a series of illustrated children’s books that he had read in Dutch as a child during the war—he hardly published a thing.

The same cannot be said of Uriel Birnbaum, who was born in Vienna in 1894 and died in Amersfoort, Holland in 1956. According to one scholar, Birnbaum produced “more than 6,000 poems, 130 essays, 30 plays, 10 short stories, 15 fairy tales, fragments of a longer epic poem, 20 chapters of a lost novel and 30 collections of illustrations.” And yet, Birnbaum received little acclaim in his lifetime. Today he is all but unknown.

Count Polzer-Hoditz’s monograph, which extols Birnbaum to the point of near worship, laments this neglect. My father’s pages continue with a loose translation from the German: “Great artists always suffer the same fate,” it begins, “the fate of genius unrecognized. Such a genius is among us.” Polzer-Hoditz declares that “few living poets deserve the Nobel prize more than he,” and goes on to describe Birnbaum’s work as a visual artist: his paintings, drawings, and book illustrations. Acknowledging that it may seem unusual for a non-Jew to lead the chorus of praises for this Jewish poet-artist, he insists that “it is a matter of honor for non-Jewish Austrians to acknowledge him as a major contributor to world literature” and that “Jews will honor themselves when they celebrate Uriel Birnbaum.”

I doubt that honor, Jewish or otherwise, had much to do with my father’s decision to take up the painstaking job of translating some 50 of Birnbaum’s poems, faithfully adhering to the complex poetic forms he used. It may have been a family connection that led to the project. My grandfather, Jacob Samuel Taubes, a minor Yiddish poet, was a friend and admirer of Birnbaum in Vienna. In fact, Birnbaum created the bookplate for my grandfather’s slim volume of Yiddish sonnets, Sonnaten Fun a Mamin (Sonnets of a Believer).

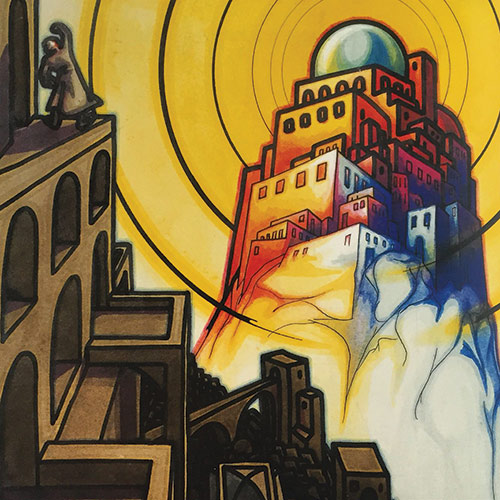

As a child, I was enchanted and somewhat mystified by a beautiful book we inherited from my grandfather, written and illustrated by Birnbaum, called Der Kaiser und der Architekt: Ein Märchen in fünfzig Bildern (The King and the Architect: A Fairy Tale in Fifty Pictures). I would often leaf through its glossy, thick pages, enjoying what I was sure was a children’s storybook. I didn’t need to understand the German text to grasp the simple storyline. The pictures told the tale of a kindly king who has a vision of a glorious, perfect city and commissions an architect to build it for him. The architect builds city after elaborate city, each illustration evoking a stained-glass window, with deep blues and purples, bright yellows, oranges, and greens that reminded me of melted lollypops, almost liquid in their richness. None of his efforts, however, comes close to the heavenly city of the king’s vision. I was disturbed that this fairytale didn’t end with “happily ever after,” but rather in failure and frustration.

I think the main reason my father spent so much time on Birnbaum’s writings was that he simply loved translating, loved keeping several linguistic balls in the air at the same time: finding the precise English equivalent for a word that best conveys the poet’s intention, remembering that he would need to come up with apposite rhymes for that word, all the while keeping his eye on the number of syllables per line. I would often see him in the kitchen tapping out stressed and unstressed syllables with his fingers on the table, quietly mouthing the words. There may have been other reasons for my father’s dedication to Birnbaum; his enthusiasm was so infectious, I never thought to ask him about it. Nor did I ever ask him why he thought Birnbaum’s work was so poorly received by his contemporaries or why he is still overlooked today.

Most of the poems my father translated are sonnets, 15 of which are based on the first four chapters of Genesis. Almost midrashic in their approach, they fill gaps in the narrative by entertaining questions that would likely never have occurred to even thoughtful readers of the Bible. How did Eve feel when she first laid eyes on Adam? What did Adam think happened to Eve’s body after she died? Who showed up for Adam’s funeral, and what were they feeling?

In “Cain at Abel’s Grave,” the poet wonders not about Cain’s emotional state at the time of the murder of his brother, but rather about how Cain would perceive the act much later, after years of restlessly wandering the earth. His conclusion takes us by surprise:

In Eden it was night. Rings of bright flame

Blazed from the swords of angels, whirling, vast.

Cain clambered strenuously till he came

To the wall’s summit—and leaped down. Steadfast,

Supported by his metal staff, he passed

Through Eden’s darkly sweet pervading scent,

Searching until he found the grave at last,

And spoke, as if in greeting, his head bent:

“Abel, I did not come here to repent

That deed of fury I could not restrain.

The weary centuries I underwent

As wanderer brought me—with new fury and disdain:

You never knew life’s hardships, nor life’s pain;

I readily would strike you dead again!”

Another sonnet in the Genesis series, “Division,” seems to have kabbalistic undertones:

When loneliness caused Adam intense pain,

God, who created him in such perfection,

Spoke with derisive anger and disdain.

“I made the man to be a light, reflection

Of total unity, but his election

As wholly one, like me, without a trace

Of discord, is transformed into rejection.

Divided now and twofold be his face,

Let the world be for him a shrunken place,

Split into bright and dark light equally.

Yet since my justice still is also grace,

Let him find joy in the illusory,

And manage to return home blamelessly.”

Thus unity became duality.

Birnbaum was gravely injured in World War I, and his war poems have an altogether different feel. They are precise, vivid, and unflinchingly candid:

The beasts, exultant in shrill ecstasy,

Circle me, coming closer as they plan

To smash the whirling world maniacally. . .

—“I can’t walk! Help me! Over here! Corpsma-a-a-n!”

Birnbaum also describes his psychological state after the war:

Since you’re a murderer, be a man as well:

You! You yourself! You have shot people dead!

You aimed, you! You yourself fired the shell!

The blood that flowed has dyed your own hands red.

The poem ends with a self-flagellating couplet, which my father rendered as “Forget duress and orders. Think the worst: / God’s judgment will condemn you to be cursed!”

Count Polzer-Hoditz had marveled at the “enormous spiritual power there must be in such a weak body, to be able to observe and judge at such moments.”

In fact, in 1913, Birnbaum had undergone a religious epiphany: “In one single night, in a strange vision, I became a believer, and since then, I believe literally in God.” Thereafter, his commitment to traditional Judaism as he understood it was absolute; both he and his father moved from political Zionism to an antipolitical Orthodoxy. In Birnbaum’s view, God desires that the world be just as it is, and it is hubris and even dangerous for man to try to improve it. All man can do is wait for God’s salvation. “He rejected all utopian schemes for improving the world or the human lot as basically blasphemous,” writes Bernhardt Blumenthal, and “certainly, one reason for the neglect of Uriel Birnbaum is his unstinting conservative religious orientation, which set him apart from his avant-garde contemporaries.” This, of course, is the meaning behind that parable of the king and the architect that I puzzled over as a child. The city of God, Birnbaum warns, can never be built by men, and any attempt to do so will end in disaster.

I have not been able to find our copy of Der Kaiser und der Architekt, and, like so many other things of my father’s, I’m afraid it’s lost forever. Other than a vague memory of rubble and collapsed buildings, I had not remembered exactly how the book ended. It turns out that I wasn’t exactly wrong; there is an image of ruin. However, the book actually returns to the vision of a perfect, heavenly city bathed in light at the very end. Birnbaum’s book is not, then, a sweeping critique of all human endeavor, but only of that which elevates man to the exclusion of God.

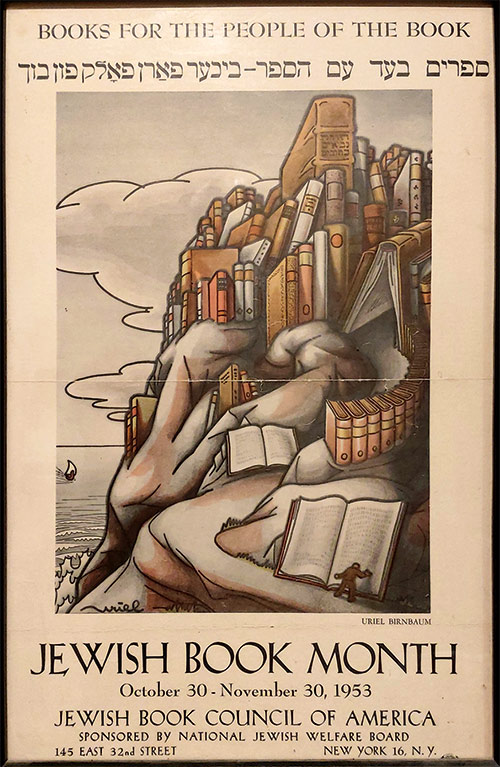

Growing up, I remember a small framed poster we had of a Birnbaum painting, which the Jewish Book Council used to advertise Jewish Book Month, 1953. The scene is of an imposing mountain with an ocean behind it, the style reminiscent of Japanese prints, a jagged crest of a wave and a tiny white sailboat in the background. The mountain peak reaches high up into the clouds, another Tower of Babel. This mountain, however, is made entirely of Jewish books, and a Tanakh with Hebrew lettering sits at the very top. A small figure of a man is making his way up, reading, learning Torah, as he goes. This, Birnbaum is clearly saying, is the only worthwhile enterprise for man: to scale the mountain one book at a time, ever striving towards the word of God.

Birnbaum thought of himself as an artist with a calling (“I gazed below, and horror made me weak / The angel kissed me on the lips: ‘Now speak!’”). My father would have made no such grand claims, but I do wonder how he saw himself in the world. I’m curious precisely because—although he spoke many languages; was fluent in literature, history, art, and music; possessed an insatiable intellectual curiosity; was blessed with an excellent memory and gifted hands—he hardly produced anything that was entirely his own. For his personal entertainment, he translated other people’s works, and as a profession, he taught students other authors’ writings.

Moreover, as a teacher, he was far less concerned with telling students what he had to say about a given subject and much more interested in encouraging them to hone their own ideas and opinions. He was a great believer in the need to revise, to edit, to pare away the extraneous, to say only what you mean, to say it accurately and well. He had high standards, but he was able to draw out of you more than you ever thought you had. In a sense, he was the opposite of Birnbaum, whose life was a whirlwind of activity, painting, writing, drawing, nonstop, amassing an enormous body of work. And yet, I now see that they were similar in some ways. Both deflected the attention away from themselves, refining, enriching, and elevating us as they did.Birnbaum directed our sights toward what is above us, and my father toward what is inside of us.

After escaping Austria in 1939,

Birnbaum spent his last years in

Holland, where, according to Blumenthal,

he spent his time writing “poems of despair, leave-taking, and humorous animal

verse.” My father translated one of those leave-taking

poems, “The Warning,” in four rhymed couplets:

Death, still unseen, just now has sent

An early sign of his intent.

The left arm and left leg, though still

My own, hardly obey my will.

After the stroke, they will not do

Things just the way I want them to.

They are my body’s first two parts

That want their freedom; so it starts.

My father himself received no such warning. He felt fine one day and was diagnosed with advanced cancer the next. Four months later, after a blur of hospital visits, treatments, improvements and setbacks, degradations, and uplifting moments of grace, he died. One of the last weekends of my father’s life, my husband and I visited him in the hospital. We brought some home-cooked food and his worn copy of one of Birnbaum’s books. We sat with him on Friday night for hours eating, singing, laughing, listening to him read and discuss the poems, flipping through the book to look at the illustrations, completely forgetting where we were.

We hung on his every word, not wanting it to end. Like all great teachers, with genuine joy he lured us into his sphere, gradually bringing us to share his excitement. I cannot remember a single thing of what he taught us that night; all that remains is my image of him then—his baritone voice, his eyes wide, a big smile on his lips.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Jokes and Justice

We were sitting in our apartment one evening when a Spanish philosopher dropped in ...

Facing Faces

Nearly every morning since October 7, I open my phone and look at the faces of the war’s most recent victims. I gaze at these portraits fearfully, searching for a…

Videos from Our 2nd Annual Conference

Subscribers and registered users can now watch four sessions from our 2nd Annual Conference, held November 2016 in New York City.

Reader Review Competition

Review a book for us and perhaps win a book in return!

Martin Greenhut

Judy, Your father and I were close friends while students at YU. He spent weekends with me at my home on Long Island, NY. I met him while on line to register as a student at YU and he arrived in the line next to me accompanied by his Father.. I spoke to him the week before he died on the telephone, hoping to renew our friendship. Leo is a very wonderful person, Judy. He brought very much goodness into my life.