Dangerous Liaisons: Modern Scholars and Medieval Relations Between Jews and Christians

In the spring of 1942—which, as Mel Brooks noted, was “winter for Poland and France”—Salo Baron published a boldly revisionist article on “The Jewish Factor in Medieval Civilization,” based on his recently delivered presidential address to the American Academy for Jewish Research (AAJR). Baron, who was born in western Galicia in 1895, had earned his rabbinical ordination and various doctorates in Vienna, and served as the Miller Professor of Jewish History, Literature, and Institutions at Columbia University beginning in 1930. Although he was famously familiar with every period of Jewish history, Baron chose to devote his lecture to the Jews of medieval Europe with a somewhat startling thesis. “Any comparison with the legislation of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy,” he asserted, “will reveal that we are maligning the Middle Ages when we call the Nuremberg Laws a reversion to the medieval status.” He stressed that “medieval Jewry, much as it suffered from disabilities and contempt, still was a privileged minority in every country where it was tolerated at all.”

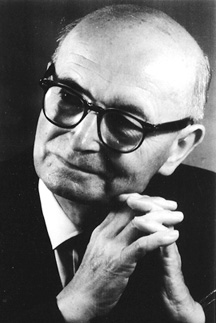

These comments, as Robert Liberles noted in his 1995 biography of Baron, Salo Wittmayer Baron: Architect of Jewish History, continued Baron’s famous critique of the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history” that he had first expressed in his influential 1928 essay “Ghetto and Emancipation” and broadly translated into practice in his three-volume A Social and Religious History of the Jews, published in 1937. There he had written that “the widespread belief that Jewish life in medieval Europe consisted in an uninterrupted series of migrations and suffering, of disabilities and degradation, is to be relegated to the realm of misconception,” adding that the Middle Ages were not “as dark for the Jews, in comparison with the rest of the population, as is still widely believed.”

The misconceived narrative that Baron boldly set out to overturn owed much to the great 19th-century German-Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz, who saw the history of his people, particularly in the Middle Ages, as having been “characterized by unprecedented sufferings, an uninterrupted martyrdom, and a constantly aggravated degradation and humiliation.” Graetz dramatically described German Jewry after the First Crusade as “cloaked in a spirit of sadness and walking in darkness all day long,” asserting further that “their appearance and manner expressed sorrow and subservience.” Baron clearly had such passages in mind when in a footnote to his 1942 essay he distanced himself from “the eternal self-pity characteristic of Jewish historiography.”

Of course, Baron was thinking not only of lachrymose Jewish historians but also of Europe’s new Aryan masters. In stressing the “the closeness of social intercourse between medieval Jews and Christians,” he clearly alluded to Hitler’s Nuremberg Laws, which prohibited marriage and sexual relations between Jews and Aryans. And yet, in the Middle Ages, he wrote such closeness “often broke down the walls of segregation, even in the most obscure and outlawed domain of sex relationships.” Furthermore, “intermarriage, and still more, illicit relationships, were far more frequent than is indicated by the sources.”

There may have been a more local impetus behind Baron’s AAJR lecture as well. A decade earlier he had succeeded the brilliant Johns Hopkins medievalist David Blondheim as corresponding secretary of the AAJR. Blondheim had been forced out of office, albeit not out of the Academy itself, after marrying Eleanor Lansing Dulles, a Bryn Mawr graduate and minister’s daughter, whose older brothers were Allen and John Foster Dulles. The couple had met in Paris, where she was researching the French franc for her doctorate in economics and he was researching the vernacular French of medieval Jews. Their first kiss took place, as she later wrote, “in the shadow of Notre-Dame’s deserted moonlit square.” (One wonders whether Blondheim showed her the monumental sculptures of Ecclesia and Synagoga, personified as females, on the cathedral’s west façade, a vibrant and triumphant Church juxtaposed with a blindfolded and drooping Synagogue.)

Eventually, after a civil marriage, their union was re-formalized in a religious ceremony performed by Eleanor’s brother-in-law, a Protestant minister. The bride, as she later recalled, told him that he could “do any kind of service he thought suitable, with Jesus included, but it would be nice to leave Christ out of it” (emphasis hers). Despite these efforts at accommodating the religious sensitivities of both sides, the marriage ended tragically less than two years later with David’s suicide, while Eleanor was carrying their first child. “I did not know the reason for his death. More than forty years later I still do not know,” she later wrote. Whatever the reason or reasons, Blondheim’s treatment by some of his colleagues in the AAJR, particularly its previous (and founding) president Louis Ginzberg of The Jewish Theological Seminary, could hardly have enhanced his nuptial life. Other colleagues were more understanding. “I cannot tell you how sorry I am that our pleasant and effective cooperation in the interest of the Academy cannot go on as heretofore,” wrote Alexander Marx, JTS’s learned librarian who had succeeded Ginzberg as the AAJR’s president. Marx, who had known Blondheim for decades, later encouraged and assisted Dr. Dulles in publishing the second volume of her late husband’s French monograph on the loan words in Rashi’s Talmud commentary.

Of course, whatever Baron’s personal and political agendas in writing it, his 1942 address was, above all, a call for a bold new historical research program.

In short, the entire realm of sexual interrelations, extremely important not only for the racial history of both groups, but also for their social coexistence, its impact upon mutual friendships or hatreds and the success of anti-Jewish propaganda . . . would merit much more searching investigation than has been given to it thus far.

But how could this be done? In a lengthy footnote Baron suggested that “a large, hitherto almost unexplored, body of materials for mixed amorous relationships may be culled together from medieval belles-lettres which, though fictional in nature, undoubtedly reflect life’s daily realities at least as much as the normative sources.”

Among the medieval sources Baron mentioned was the Dialogus miraculorum (Dialogue on Miracles) by the Cistercian monk Caesarius of Heisterbach (d. 1240), two of whose stories involve sexual relations between clerics and young Jewish women. In one of these a young English cathedral canon falls helplessly in love with a beautiful Jewish girl with whom he has sexual intercourse, at her invitation, on the night following Good Friday. After the canon confesses his guilt to his bishop, he is persuaded to renounce his Church career and marry the girl—after her baptism. In her excellent recent book The Jew, the Cathedral, and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century, Nina Rowe writes that such medieval fantasies of “sexually provocative” Jewish women “were sometimes associated with the figure of Synagoga herself.”

Were there indeed “sexually provocative” Jewish women in medieval Europe, or only fantasies about them? And were these fantasies harbored only by Christians? One Hebrew source dealing with the background to the 1171 ritual murder accusation in Blois, on the Loire, repeatedly mentions a Jewish woman named Polcelina, whose close relations with Count Thibaut apparently led to the outbreak of murderous hostility against the local Jews, more than 30 of whom were burnt as punishment for the alleged murder of a child whose body was never found.

This Hebrew chronicle, composed late in the 12th century by Ephraim of Bonn, was interpreted by Heinrich Graetz as suggesting that the mayor of Blois “bore a grudge against an influential Jewish woman . . . who was a favorite of his lord . . . and took this opportunity of revenging himself.” The opportunity presented itself, as we learn from Ephraim, when a local servant saw a Jew watering his horse alongside the river and mistook an untanned hide sticking out of his coat to be the body of a child. The servant, in Ephraim’s telling, knew that his lord “would rejoice” upon hearing the news, “since he hated a certain haughty Jewess in the town.” Upon hearing of the alleged incident the lord replied: “Now I shall take my revenge from that woman, Madame Polcelina.”

But which local lord hated Polcelina, and why? In Graetz’s reading, it was not Count Thibaut who now hated her, but the local mayor, who was jealous of the count’s relations with the “haughty Jewess.”—Although it is not clear that such a mayor existed, this questionable storyline, which sundered Polcelina’s erstwhile Gentile lover from the Gentiles who now hated her, was later followed by Baron, who wrote in 1957 that the local investigation into the servant’s suspicions “became entangled in Count Thibaut’s love affair with a Jewess . . . and the enmity of local officials toward the count’s exacting lady friend.”

From the 1960s on, however, a different historical reconstruction began to emerge: It was the count’s change of heart towards Polcelina that set the stage for the tragedy in Blois. In his Medieval Jewry in Northern France, Baron’s student Robert Chazan asserted that Polcelina “had unknowingly lost her leverage with the eroding of princely ardor.” Another former student and perhaps Baron’s leading disciple, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, suggested a more developed scenario in his now classic book on Jewish history and memory, Zakhor. In Yerushalmi’s version, “Count Thibaut was having an affair with a Jewess, Polcelina, which aroused the jealousy of the count’s wife, while other Christians resented the lady’s influence at court.” Although the Hebrew chronicler had referred to Thibaut by his actual name, he had assigned the count’s wife the archetypal name of “Jezebel.” Since the 1953 publication of Shalom Spiegel’s classic Hebrew article on the martyrs of Blois we know both her real name and her royal pedigree. She was Countess Alix, the second daughter of Louis VII by Eleanor of Aquitaine, who was born shortly before their divorce. By the time she married Thibaut (Theobald) V in 1164 his sister—also known as Alix—had become Louis’ third wife. The relationship between a local aristocrat who was so closely connected to the royal chamber and a Jewess was bound to become the subject of gossip among both Jews and Christians—and perhaps even between them.

Readers who have been sensing the dramatic possibilities of the story may not be surprised to learn that a Hebrew play was indeed written about Polcelina, Thibaut, and the Blois martyrdom of 1171. More surprising, however, is the identity of the playwright: Shelomo Dov Goitein (1900–1985), who along with Salo Baron must be counted as among the 20th century’s greatest Jewish historians. Goitein is best known today for his extensive and meticulous use of documents from the Cairo Geniza to reconstruct the social and economic history of medieval Mediterranean Jewry, but when his five-act play was published in Tel Aviv during the summer of 1927, Goitein had not yet inspected a single Geniza fragment, although he had recently earned a doctorate in Islamic studies at the University of Frankfurt. Having arrived in Palestine before The Hebrew University of Jerusalem opened its doors, Goitein spent his first few years in the country teaching at Haifa’s Reali high school. There one of his colleagues was the equally overqualified Shalom Spiegel. Of those two future titans of Jewish scholarship only Goitein was hired by The Hebrew University, joining its Institute of Oriental Studies in 1928. Spiegel made his way to New York shortly thereafter, eventually joining Louis Ginzberg and Alexander Marx at The Jewish Theological Seminary.

Polcelina was completed in Jerusalem early in the spring of 1927. It is likely that when he began composing the play, Goitein was considering the idea that he might support himself as a Hebrew writer like his friend the future Nobel laureate S. Y. Agnon, one of the three friends he thanked in the play’s postscript. Another was Berl Katznelson (1887–1944), the founding editor of the Labor Zionist newspaper Davar. It was in the pages of Davar that Shalom Spiegel’s tripartite review of Goitein’s play appeared in October 1927.

Spiegel, an expert in medieval Hebrew liturgical poetry whose brother was Sam Spiegel, the great Hollywood producer, opened his review by quoting from a penitential prayer (selicha) composed by the chronicler Ephraim of Bonn after the burning of Blois’ Jews (he also quoted one from Ephraim’s brother Hillel). In one of the poem’s more wrenching passages, Ephraim wrote:

I am stoned, I am struck down and

crucified. I am burned, my neck is

snapped in shame. I am beheaded and

trampled on for my guilt. I am

strangled and choked by my enemy

These lines are taken from T. Carmi’s 1981 translation. Carmi, himself a poet, wisely did not seek to emulate the poem’s complicated rhyme scheme, but neither did he seek to sidestep or soften those lines in Ephraim’s poem that might grate on some late 20th-century ears. Not only did he include the poet’s description of his coreligionists as “crucified” (Ephraim was not the first Hebrew liturgical poet to compare the fate of medieval Jews with that of Jesus), but he also included the poet’s raw request for divine revenge:

May disaster strike all my evil neighbors! Woe upon them!

They have earned their own disaster by destroying me.

Spiegel had evidently first encountered this poem in Simon Bernfeld’s recent anthology Sefer ha-dema’ot (Book of Tears, 1923–1926), where it followed an account of the Blois incident taken from Joseph Ha-Kohen’s 16th-century history of Jewish suffering Emek ha-Bakha (Vale of Tears). Goitein had also read Bernfeld’s anthology, to which he referred in the learned notes to his 1927 play. Unlike Bernfeld, however, Goitein also consulted the two original medieval chronicles of the Blois incident. Bernfeld, true to his anthology’s title, was primarily interested in eliciting tears, and for his purposes it was sufficient to include Joseph Ha-Kohen’s later account of the events in Blois. Salo Baron, who arrived in New York during the late 1920s, had also been perusing Bernfeld’s anthology, probably with some degree of irritation. His polemic against lachrymose history in “Ghetto and Emancipation” may be seen as a response not only to 19th-century historians like Graetz, but to Bernfeld’s Sefer ha-dema’ot. In fact, as the literary scholar Yael Feldman has recently suggested, Bernfeld’s title “may have . . . inspired Baron’s ironic phrase ‘the lachrymose conception of history.’” Goitein’s play of the previous year can be read as another response to Bernfeld, albeit one which sought to humanize rather than minimize the subject of Jewish suffering.

In the final scene of Act 1 the mayor of Blois—a figure of whose existence Goitein had apparently been persuaded by Graetz—soliloquizes about Polcelina’s contemptuous conduct:

What did she say to me on that day? “Insolent goy!” “goy,” “goy,” cursed be the power of that word . . . “Goy” means you are not a person, your word does not insult, your blow does not cause pain . . . I will dispel that word from your mouths! . . . I will pursue you in anger and destroy you from under the heavens of France.

Unlike Graetz, who had depicted the mayor as jealous of the relations between the “haughty Jewess” and his own powerful lord, Goitein presented him as understandably rankled by her insolent manner of addressing him.

Polcelina’s imperiousness was evidently suggested to Goitein by Ephraim of Bonn’s reference to her as gevartanit, a strong woman (perhaps even a “manly” one). This trait is depicted in the play’s very first scene, which takes place on a Saturday afternoon during the spring of 1171. While strolling along the Loire, the mayor mentions the object of the visiting count’s affection, to which the latter replies sardonically: “Oh, thank God, the subject of Polcelina has come up.” Then, echoing Ephraim’s chronicle, Thibaut refers to her as “that imperious woman,” and acknowledges that she had once slapped “a certain nobleman” when he had allowed his hands too much freedom.

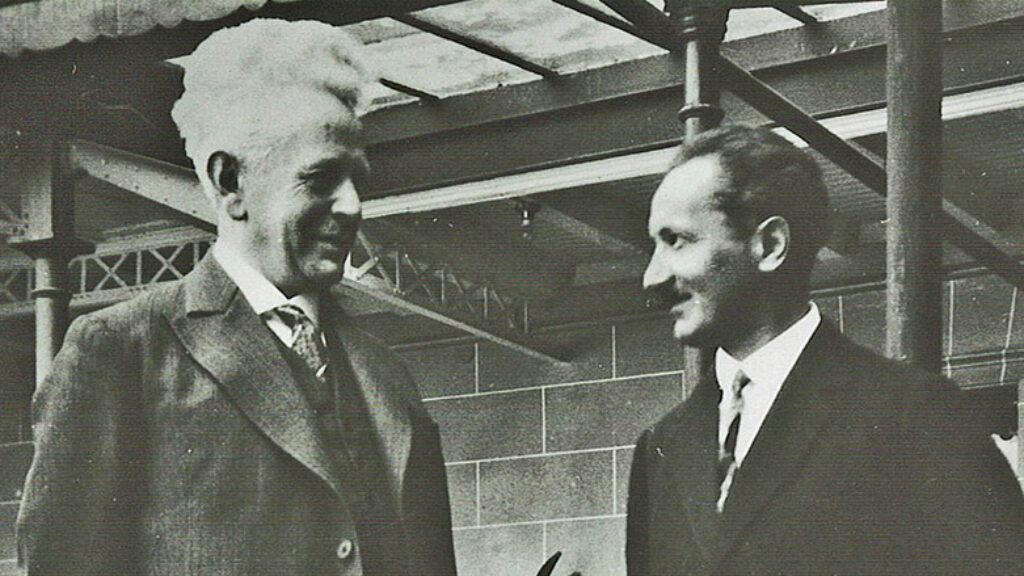

Right: Eleanor Lansing Dulles, ca. 1930s. (Courtesy of the Eleanor Lansing Dulles Papers, Special Collections Research Center,

The George Washington University.)

Goitein portrayed Polcelina as a wily widow aware both of the count’s unrelenting desire for her and of the rumors concerning their alleged affair. His Polcelina continues to keep the count at arm’s length even after realizing that she is thereby endangering her community. When Polcelina reluctantly agrees, after her coreligionists are accused of ritual murder, to meet with Thibaut privately she scoffingly challenges him to take her by force: “Yes, Polcelina is a piece of meat” (a learned allusion to a talmudic passage in Nedarim). When the count explains that he does not want her on those terms, she hisses back: “Take her, you dog! A carcass is permissible to you, goy!” In the play’s second scene one of her coreligionists describes Polcelina as a cross between Esther and Vashti, treating both circumcised and uncircumcised with equal contempt. Another Jew comments on Polcelina’s distinctive demeanor while leading the local women in prayer during the High Holy Days—looking, he claims, as if she were propositioning the Deity. “Were I God himself at that moment,” he adds, “I would be afraid of her.”

One character who definitely fears her is her adolescent son Tov-Elem. Spiegel noted in his 1927 review that Goitein had invented not only the name, but also the character. While acknowledging that he “did not know of a historical work in our literature that so faithfully reflects research in all sources of the period,” he also praised the playwright for having the courage to occasionally improve upon historical truth—as in exchanging Polcelina’s two daughters for a single son, whom on one occasion she threatens to disown “if he does not become another Rashi, or at least something close.” One wonders if this improvement upon the historical record was not rooted in Goitein’s own youthful experiences as the scion of a distinguished rabbinical family.

A final “improvement” upon the historical evidence appears in Goitein’s dramatic depiction of Polcelina’s death. Both medieval chronicles dealing with the martyrs of Blois, as well as two of the liturgical poems, stress that while waiting to die they sang the Aleinu prayer, which (in uncensored versions) refers to both Jesus and Christianity in rather uncomplimentary terms. “As the flames mounted high,” wrote the medieval chronicler Ephraim of Bonn, “the martyrs began to sing in unison a melody that began softly but ended with a full voice.” He adds that the Christians reportedly asked: “What kind of song is this, for we have never heard such a sweet melody?” Although Ephraim, in his accompanying poem, depicted the Jews as joyfully offering themselves to God as a “burnt-offering,” his brother Hillel chose a different biblical allusion:

As they were being brought out to be burnt,

they rejoiced as a bride being led to her wedding canopy.

Reciting alenu le-shabeah with souls full of rapture,

“Behold thou art fair my love, behold thou art fair.”

That last line, as many readers will recognize, comes from the fourth chapter of the Song of Songs; Hillel has the martyrs of Blois serenading the divine beloved whom they hope soon to join in marital rapture. The link between martyrdom and Eros already developed by Rashi in his commentary on the Song of Songs recurs later in Hillel’s poem, where the 17 Jewish women being led to the pyre are described as “each hastening the other to move ahead quickly . . . with joy and gladness they enter the palace of the king.”

Both poems seem to have shaped Goitein’s poetic rendering of Polcelina’s last words. As in Ephraim’s poem, she beseeches God: “Let this sacrifice be accepted as a sin offering on behalf of the Jewish people,” but then, using imagery from the Song of Songs she describes herself as God’s eager betrothed:

My beloved descended into his garden to inspect his rose

and see if its time is ripe. I replied to him: I am ripe.

Spiegel, who considered these lines to be “the best of all attempts at poetry in the play,” undoubtedly recognized the influence of Hillel’s medieval poem.

As it happens, Goitein’s play about love and death in the medieval Jewish-Christian encounter appeared in the same year in which the medievalist David Blondheim and the economist Eleanor Dulles were secretly engaged in Paris, and only a year before Salo Baron’s first attack on “the lachrymose conception of Jewish history.” As Baron would later write, “every generation writes its own history of past generations.” This, as theatergoers know well, is also true of playwrights. Perhaps our own generation is ready for one who will present David and Eleanor’s modern story of love and death as boldly and sensitively as Goitein presented that of Polcelina and Count Thibaut during the 1920s.

Suggested Reading

Overturned Tables

Despite his incontestable Jewishness, Jesus never participated in a Seder as the Mishnah describes it any more than he intended for Judeans to abandon biblical law for the worship of God’s only begotten son.

Fatal Attraction

Although Martin Heidegger joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and never forthrightly repented of the episode “no other philosopher had more impact on twentieth-century European Jewish thought.”

Rallying Round the Flags

Derek Penslar's new book returns to aim Jewish soldiers of the diaspora to their rightful place in Jewish history.

Nobody Expects

I mug at myself in the mirror and recite the old Monty Python gag.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In