Tamar, Helen, and Love’s Ambition

In Joseph and His Brothers, Thomas Mann describes “a woman . . . seated at the feet of Jacob, the man rich in stories, in the grove of Mamre or near Hebron”:

They often sat like this, whether in the tent of felt, close to its entrance, at the same spot where the father had once sat with his favorite and let himself be coaxed out of that colorful garment, or under the oracle tree or at the edge of the well that adjoined it, where we first met that clever lad by moonlight and his father leaned on his staff to gaze in concern at him. How is it that this woman is sitting with him now, be it in one place or the other, her face upraised to listen to his words? Where does she come from, this young and earnest woman whom one finds sitting at his feet quite often, and what sort of woman is she?

The woman in question is Tamar, whom the Bible barely describes at all, considering the extraordinary and highly unusual role she plays in the family romance of Genesis and the larger story of Israel. Tamar is the mother of Peretz and therefore the ancestor of David and, ultimately, through David, of the messiah. She comes to motherhood, however, not through the normal course of marriage but through an exceptionally brazen act, seducing her father-in-law, Judah, while veiled in a harlot’s disguise. This so alarmed the rabbis that much of their commentary on her behavior is a kind of midrashic cover-up.

Mann’s exceptional achievement in creating his version of Tamar was not merely to unveil what the rabbis re-veiled but to reveal something essential that is hidden in the biblical text itself: the deeper reason for Tamar’s actions. As he writes: “She wanted to interpolate herself—and did so with astonishing determination—into the grand story, into the vast play of events, about which she had learned by way of Jacob’s instruction, and she was not to be left out of it at any price.” Tamar, in other words, was not merely a seducer; she herself was seduced by the prospect of being part of the national story of Israel, a story she learned about at Jacob’s feet.

Is that idea, that the ancestor of David inserted herself into the narrative on her own initiative, troubling? I think it is, and I think that it is the deepest reason why rabbinic commentary on the story of Tamar has tried so hard to keep her under wraps.

Though both the commentators and Thomas Mann take pains to identify her ancestry, in the biblical text, Tamar is not given a genealogy or even an ethnicity. She is simply the wife chosen by Judah for his eldest son, Er, born to him by his Canaanite wife, Shuah. All we know of Er besides his parentage and his marriage is of his failures: he was childless and wicked and slain by God for the latter. Judah then marries Tamar to his second son, Onan, instructing him: “Join with your brother’s wife and do your duty by her as a brother-in-law, and provide offspring for your brother.” (Gen. 38:8).

This is the first reference in the Bible to levirate marriage, whose laws are later expounded in Deuteronomy. When a man dies without issue, his brother is supposed to do the duty of “raising up” sons in his name by taking his widowed sister-in-law as a wife. The levirate obligation is disturbing to modern ears; the Tamar story suggests that it may have troubled ancient ears as well, for Onan refuses to do his duty. He marries Tamar, but “when he would come to bed with his brother’s wife, he would waste his seed on the ground, so as to give no seed to his brother” (Gen. 38:9). For this, Onan, too, is slain by God.

At this point, Judah apparently begins to worry that marrying Tamar was a dangerous proposition. He promises her his third son, Shelah, but tells her to remain a widow until he is grown. And so Tamar waits, even as Shelah comes to manhood and is not given to her, until an opportunity presents for her to escape her widowed and childless fate.

When Judah’s wife dies, and he has completed his period of mourning, he travels with his friend Hirah the Adullamite to a sheepshearing in Timnah. Learning of this, Tamar takes off her widow’s clothes, dons a veil to disguise herself as a harlot (zonah), and places herself at the entrance of Enaim on the road to Timnah, where Judah will see her. He does and offers her a kid from his flock as payment to sleep with her. She agrees but demands a pledge to hold until payment: his signet, cord, and staff.

Thus Tamar gets pregnant not by her brother-in-law, as the levirate law commands and her father-in-law promised, but by her father-in-law himself. Judah sends the promised kid with Hirah, but of course he cannot find Tamar because she has returned to Judah’s house and her widowhood. When Tamar’s pregnancy becomes obvious, Judah calls for her to be burnt to death for harlotry, at which point she produces the tokens of his own pledge, and Judah confesses his guilt both in having intercourse with her and in not giving her his third son as a husband.

The story bears many marks of folklore. The pledge that would unmistakably identify Judah is one such; another is the trio of sons, the older two failing, which should leave the youngest to triumph. The most prominent, though, is the “bed trick” by which Tamar gets herself pregnant. In her encyclopedic study of this motif, Wendy Doniger details its many variations across world literature: stories in which a man disguises himself as a woman’s husband to seduce; in which a woman disguises herself as her husband’s mistress to kill him (or to win him back); in which a woman places a double in her bed to sleep with her husband so she can go out and meet her lover; in which two men disguise themselves as women so as to get access to the woman and wind up in bed with each other; and so on and on. The list of variants is nearly endless, as is the range of potential meanings and psychological purposes of these tales.

The most famous biblical bed trick is probably Laban’s substitution of Leah for Rachel at Jacob’s first wedding. Doniger persuasively argues that Ruth—who sneaks under Boaz’s cloak at the behest of her mother-in-law, Naomi—may be another. But Tamar’s is the most brazen. She is the only female bed trickster who acts entirely on her own initiative. More importantly, she is entirely guided by her own desire. She is not directed by a scheming older brother. Nor is she like Jesse’s wife, Nitzevet, who is said to have disguised herself as a handmaid to save her husband from temptation. Her trick is not even quite aimed at getting Judah to uphold the levirate law, since that law technically binds only his youngest son, Shelah. Why did she do it? Who or what did she desire?

Thomas Mann’s answer—that she wanted to be a part of the grand story of Israel—is more mythological than psychological. But there is another heroine who resembles Tamar in crucial ways, whose author was most interested in the psychology of such an audacious woman. That woman is Helen, the protagonist of Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well.

All’s Well That Ends Well has never been one of Shakespeare’s more popular plays. That’s partly because it has few readily quotable lines or speeches; Helen is not a nimble quipster like Rosalind of As You Like It, nor an ardent co-sonneteer like the teenage protagonist of Romeo and Juliet. But the primary reason why All’s Well has never been a crowd-pleaser is that the central storyline leaves a bad taste in theater-goers’ mouths, and it is precisely that taste that will lead us back to the question of Tamar’s desire.

Helen is the daughter of a renowned yet humble physician, upon whose death she was taken in by his lord and lady the Count and Countess of Roussillon and raised alongside their son Bertram, as if they were siblings. This Bertram is the object of Helen’s quest. In the first scene of the play, in her first soliloquy (and very nearly her first lines), Helen laments the fact that her beloved is about to leave for the court in Paris and unpacks her heart to us about its sole object:

My imagination

Carries no favor in ’t but Bertram’s.

I am undone. There is no living, none,

If Bertram be away. ’Twere all one

That I should love a bright particular star

And think to wed it, he is so above me.

In his bright radiance and collateral light

Must I be comforted, not in his sphere.Th’ ambition in my love thus plagues itself:

The hind that would be mated by the lion

Must die for love. ’Twas pretty, though a plague,

To see him every hour, to sit and draw

His archèd brows, his hawking eye, his curls

In our heart’s table—heart too capable

Of every line and trick of his sweet favor.

But now he’s gone, and my idolatrous fancy

Must sanctify his relics.

(act 1, scene 1, lines 87–103)

The pivotal line of this speech is where Helen confronts the ambition in her love. Conventionally, an ambitious woman would seek to marry above her station and use whatever seductive wiles she has to achieve this aim. But Helen, though she is distinctly lower than Bertram is in social class, perceives the difference in status between them as an obstacle, not an enticement. Moreover, as we learn when, in act two, she puts her plot to win Bertram into effect, ennoblement falls easily into her grasp. Bertram, not so much.

Helen learns that the king of France is ill and travels to Paris with some potions from her father with which she aims to cure him—extracting from him first a promise that, if she is successful, she may claim her choice of husband. She succeeds and, presented with all the most eligible courtiers of France, chooses Bertram.

Bertram reacts with shock and dismay, giving as one reason Helen’s low birth, but the king has a ready answer to this: “’Tis only title thou disdain’st in her, the which / I can build up” (act 2, scene 3, lines 128–129). Bertram, though, will not be swayed, and only the king’s express command forces him to concede. Helen’s victory is Pyrrhic, however. Shortly after the wedding, Bertram flees France for wars in Italy, leaving behind a note to his new wife promising never to live with or lie with her until she fulfills the following seemingly impossible conditions:

When thou canst get the ring upon

my finger, which never shall come off, and show me

a child begotten of thy body that I am father to, then

call me husband. But in such a “then” I write a “never.”

(act 3, scene 2, lines 68–62)

Helen, needless to say, rises to that challenge. She sneaks off to the Italian wars, where she discovers Bertram has become enamored of a virtuous local woman, Diana, whom he aims to seduce. This gives Helen the opportunity to propose the bed trick. She tells Diana to agree to an assignation, demanding Bertram’s signet ring in advance as payment, then promises to take her place on the night in question. This accomplished, Helen puts out the story that she has died so as to draw her erstwhile husband back to Paris.

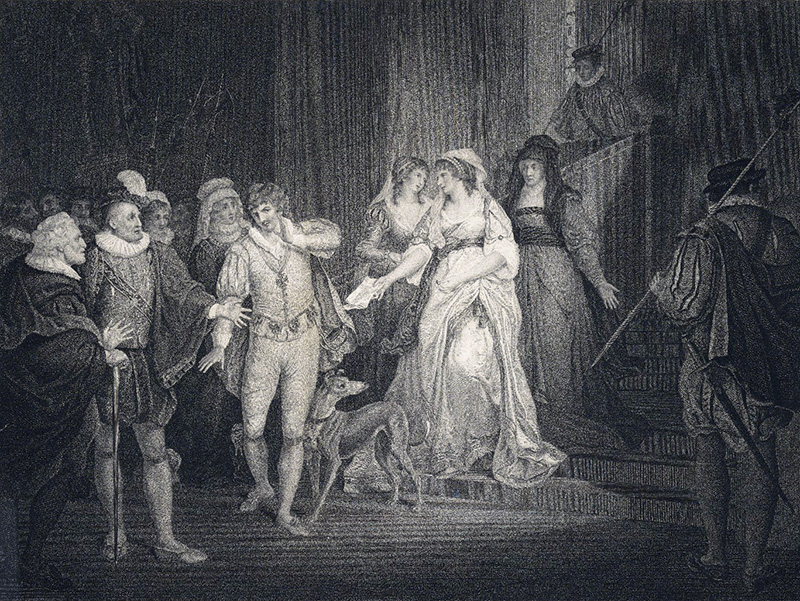

The play climaxes with a recognition scene in which Bertram, exposed for having seduced and abandoned Diana and unable to escape his web of lies, is confronted by the living Helen, who, having obtained the signet and the baby, can no longer be denied. He promises, if she can explain how on earth she accomplished all this, to “love her dearly, ever, ever dearly.”

Shakespeare borrowed the plot of All’s Well That Ends Well wholesale from Boccaccio, but the tone of the play is radically different. Where Boccaccio’s Gillette is a nimble trickster, frank in her desire for Bertrand and confidently determined to win him, Shakespeare’s Helen is anguished by her passion and loathe to disclose it. Where Boccaccio’s Bertrand is a fairly commonplace nobleman used to getting his way, Shakespeare’s Bertram fairly seethes with resentment at being made the object of desire rather than the desiring one.

All’s Well That Ends Well, in other words, is a folktale populated by fully modern, psychologically realistic characters, and the juxtaposition of the two modes is a key source of the reader’s and the audience’s discomfort. It’s one thing for a woman in a folktale to play the bed trick; it’s another for a believable woman to do it. It’s one thing for a man in a folktale to disdain being matched below his station; it’s another to hear him pouring out abuse, see her mortified reaction, and still want her to win him back in the end. Most importantly, once we accept these people as fully real, and not figures in a folktale, it’s hard to read the play’s title any way but ironically.

Yet that is what the play demands of its actors and directors. Even in the best of hands, this challenge is rarely met, and critics have generally blamed that on the inadequacy of Bertram as a romantic object. As Samuel Johnson memorably put it:

I cannot reconcile my heart to Bertram; a man noble without generosity, and young without truth, who married Helena as a coward, and leaves her as a profligate; when she is dead by his unkindness, sneaks home to a second marriage, is accused by a woman whom he has wronged, defends himself by falsehood, and is dismissed to happiness.

But this explanation of the problem has always struck me as inadequate. Plenty of other

Shakespearean heroines have loved deficient men—Portia in The Merchant of Venice, for example, loves the shallow, weak-willed Bassanio—and while we may not be reconciled to them, they don’t pose the same kind of problem that All’s Well does. But those men were the wooers; they professed their love from the first. Bertram, by contrast, protests when commanded to marry Helen: “I cannot love her, nor will strive to do ’t” (act 2, scene 3, line 156). Yet Helen simply will not accept his rejection. Her longing is too deep and too strong to be denied.

The problem that we have with Helen, even today, is a gendered one. A folktale in which a man quests for a high-born, beautiful woman who disdains him and wins her by some combination of daring, trickery, and panache would strike us as old-fashioned—and might well outrage us if it involved a bed trick—but it would still feel proper in its shape. Indeed, Bertram’s key protest from the beginning—deeper than his snobbery about blood lines—is that he be allowed to play the man’s part, to be the quester. Helen wins her chosen partner rather than attracting him; that is the deep reason the play continues to engender discomfort.

I believe the same is true of Tamar, and this discomfort is deeper than rabbinic concerns about her sexual behavior in explaining why so much commentary undertakes to hide her audacity.

Much of rabbinic commentary on the story of Tamar is concerned with the blatant sexual improprieties of the story. There is a midrash in which Judah ignores Tamar in her harlot’s disguise until God sends an angel to bewitch him and turn him back toward her. In another, Judah ruminates on his sin in deceiving his father over Joseph’s fate as the reason this shame has befallen him. In yet another, he lectures his own sons against drunkenness, blaming an excess of wine for both his marriage to a Canaanite wife and his tryst with his own daughter-in-law. All of this is in keeping with rabbinic anxieties about sexual desire that are largely foreign to the Bible.

There is no suggestion in the biblical text that Tamar was driven by sexual desire, but there is an obvious impropriety in disguising herself as a harlot and trying to seduce her father-in-law, which midrash steps in to mitigate. The biblical text says that Tamar veiled herself, so another midrash expands on this, explaining that she was so modest that she was continually veiled when in Judah’s house—indeed, he had never seen his own daughter-in-law’s face. For her modesty she was rewarded with being the ancestor of David (and of Isaiah)—a direct reversal of the plain sense of the biblical account.

To my mind, however, these rabbinic amendments are less central than those that deny Tamar the agency that is manifest in the biblical text. In one midrashic retelling, Tamar was not a Canaanite but an Aramean, and of noble stock; she was a proselyte before she came to Judah’s family, and she was a prophet. It is from an angel that she learned that Judah was going up to Timnah, giving her the opportunity to put her plan into effect, and with an angel’s help that she is able to find Judah’s pledges, the signet and the staff, through which she is saved from death. Most important, she was given the foreknowledge that she was to become the ancestor of David, which is the only justification for her extraordinary seduction of Judah.

Mann’s essential revision was to transform Tamar back into a quester in her own right: not an Aramean but a Canaanite, not a noble but a commoner, not a prophet but a spiritual seeker who came to be entranced by Jacob’s stories of Cain and Abel, of Abraham and Sarah, and of Jacob’s own trials. The key desire that was awakened in her was not primarily for children, and certainly not for Judah, but to be a part of this story. She does not know about David, but she knows that Reuben, Simeon, and Levi have each fallen out of favor for different reasons, and Joseph is no longer, so that the blessing will most likely pass through Judah. And she was determined to partake of that blessing. “She was,” Mann writes, “that ambitious. All her spiritual strivings had flowed into this inexorable and almost sinister—for the inexorable has something sinister about it—resolve.”

The audacity of Mann’s Tamar, from this moment on, is astounding. First, she imagines wedding herself to Judah, but to triumph this way would require the deaths of his Canaanite wife and his three sons, a prospect from which she recoils. So she determines to marry his eldest, Er, despite his questionable and sickly nature, and prevails upon Jacob, her teacher, to win him for her. He does, yet that marriage ends bloodily almost immediately, her husband dying of a hemorrhage on his wedding night. In need of a justification to be wed to Onan, it is Tamar herself, in Mann’s telling, who comes up with the law of levirate marriage, a law that Jacob accepts to be just and therefore promulgates. If midrash is anxious to veil Tamar behind the curtain of divine providence, Mann magnifies her into a questing figure who not only determines her own fate but establishes the law to do so.

Yet even in her audacity, Mann’s Tamar is motivated ultimately by the desire to be a part of a story that is already written and is bigger than her. This, I think, is what ultimately ties her to Shakespeare’s Helen and her own questing love. Why, after all, does Helen love Bertram so irrepressibly much, if not for any obvious qualities of his own? Harold Bloom comments on the extraordinary degree to which Helen’s love for Bertram is overdetermined by her childhood. Bertram was her playmate. Marrying Bertram is the only way to truly become her adoptive mother’s daughter, restore her family, recover a home. So, too, with Mann’s Tamar. She is a kind of adopted daughter, sitting at Jacob’s feet, and her quest is to graft herself to Jacob’s root, which she already feels to be her own.

That story—of a woman using transgressive means to force her rejecting husband to acknowledge her—has a larger resonance for the Jewish story in the modern era. From the messianism of Shabbtai Zevi to the proto-Zionism of Hovevei Zion, that era was punctuated by a deep Jewish longing for a return home. The traditional perspective on this longing was that Israel, like a proper woman, should wait for her divine husband to redeem her. Zionism, at its heart, was powered by the audacious resolve of Jews to stop waiting, take matters into their own hands, and determine their own destiny despite rabbinic prohibitions against actively reentering history and “forcing the end.” Seventy-five years after accomplishing its central aim, that resolve remains troubling for the same reason that Helen’s is and the same reason that Tamar’s is: less because of our feelings about the quest as such than because we did not expect them to undertake it.

Suggested Reading

Upon Such Sacrifices: King Lear and the Binding of Isaac

How Shakespeare helps us think about the akedah, and vice versa.

Fruit of the Fall

The forbidden fruit has been said to be anything from a fig to a banana, so how did the world settle on an apple?

Coming with a Lampoon

Jacobson is a world master of the art of disturbing comedy and each new work of his advances the genre—his latest one by a giant step.

Something Off

There was a sense of oddness about Bruno Shulz that German-Jewish writer Maxim Biller exploits in his new novella, Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In