Something Off

When Bruno Schulz was shot to death in Drohobycz—then Nazi-occupied Poland, now Ukraine—in 1942, he was 50 years old and carrying a loaf of bread. He was well-known among the prisoners of the ghetto, which had once been a normal Galician town, for his sloping walk and hypnotic aura. Before the war Schulz had been a famous writer and illustrator. Now SS officer Felix Landau was forcing Schulz to paint a mural for him at his house. Landau had a gambling debt with another SS officer, who chanced on Schulz walking home and shot him dead because he was “Landau’s Jew.”

Schulz’s death has become the stuff of literary legend, as has his slim oeuvre: two volumes of stories, which he illustrated himself, and a lost novel called The Messiah. In Poland, he was hailed as one the great stylists and received prestigious awards during his lifetime. Since being published in English in the 1970s in Philip Roth’s “Writers from the Other Europe” series, he has become a writer’s writer. Both Roth and Cynthia Ozick turned to fiction to speculate about his fate and his lost novel in the 1980s—Roth in The Prague Orgy, Ozick in The Messiah of Stockholm. Jonathan Safran Foer has called Schulz’s 1934 collection The Street of Crocodiles his “favorite book.” And David Grossman went so far as to claim that reading Schulz inspired him to become a writer.

With Schulz, writes Grossman, inanimate objects come to life. Buildings breathe, people are like animals, and animals are like people; Schulz’s world is frightfully alive. “The silence of that third hour after midday extracted from the walls of houses the pure whiteness of chalk and spread it voicelessly, like a pack of cards,” reads his description of an afternoon in a small town. This prevailing sense of being overwhelmed by the world runs through Schulz’s writing, and it in turn overwhelms the reader.

Schulz’s prose is endlessly eloquent, yet his perspective itself is strangely childlike. His protagonists are typically named Jozef and are on the threshold of puberty. They are filled with a longing both infinite and indefinite, which for all its intensity is essentially naïve. The Jozef of Schulz’s second published work, the quasi-novel Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, is obsessed with a girl named Bianca, who is described as an astral being: “She was slim and linear in a white dress as if she had just left the zodiac.”

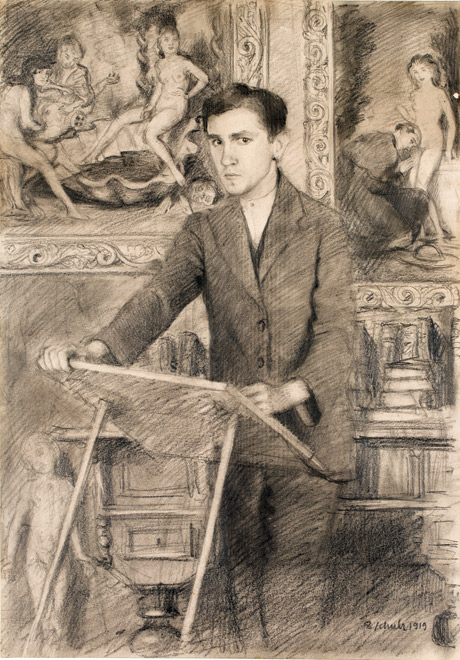

There are no hints of the terrors to come—or even the terrors of being a Jew in 1930s Poland. Schulz’s stories convey a mingling of identities, but they lack overt Jewish references. They do, however, portray an acute sense of loss for Old Galicia. His artwork, mostly pencil drawings, possesses a more demonic and unreal character. His compositions are crammed, his figures are distorted and torn, tormented, as if Francis Bacon had illustrated Galician fairy tales.

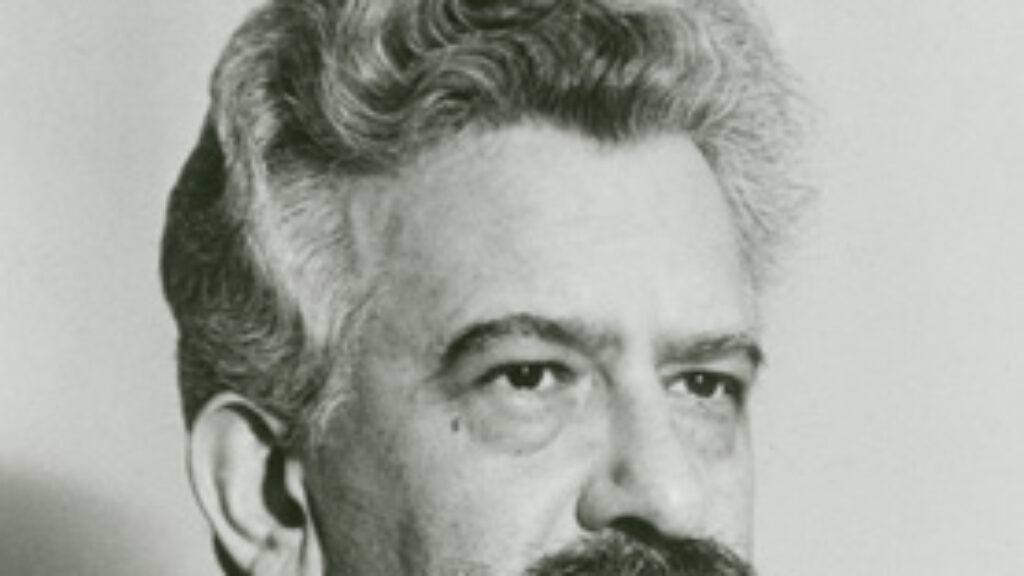

Schulz himself was a shy, timid man who bowed to everyone. That he stayed in Nazi-occupied Drohobycz seems to have been the result of helpless anxiety turned paralysis. In the few photos that survive, Schulz seems positively disturbed. There’s something odd, something off.

It is this sense of oddness that German-Jewish writer Maxim Biller exploits in his new novella Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz, out now in translation from the London publisher Pushkin Press. Previous attempts to fictionalize Schulz’s life dealt with his death and its aftermath. Biller, however, shows us Schulz as a living and breathing—and trembling—human being.

Born in 1960 in Prague to Jewish parents from Russia, Biller moved to West Germany with his family at the age of 10. Biller first made a name for himself as a contentious journalist in the German magazine Tempo, through his column “One Hundred Lines of Hate.” Raised without religion, he made the decision to be circumcised at the age of 16, and he has devoted himself to exploring the vagaries of being a Jewish man in a country where “somebody like me was not allowed for.”

In Germany, Biller is known as much for his aggression and spite as he is for his skills as a writer. On a radio show, he stated—somewhat accurately—that “people say Biller is a prick, but his writing is divine.” His role model seems to be Norman Mailer, whom he emulates in both his confidence and his misogyny, though less so in the length of his books, which tend, like this new one, to be short. In keeping with his penchant for controversy, his second novel, Esra, was banned after a court found that it infringed on the personal rights of a well-known actress and former girlfriend, who was the model for the novel’s eponymous female protagonist.

In Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz, Biller again draws rather freely on the life of another to create a vehicle for his own personal struggles. It is set on a warm November day in 1938; Schulz is taking a day of sick leave from his dreaded job as a high school teacher to write a letter to “Herr Thomas Mann.” He seeks to inform the German writer that a man claiming to be Thomas Mann has taken up residence in Drohobycz and is acting rather strangely, demanding a list of all the town’s Jews. Schulz then attaches a short story he wrote in German, with the hope of having it published in a German journal.

He is interrupted frequently by visions of his co-teacher Helena—“small, athletic and with a hairy face like a clever female bonobo chimpanzee”—who, much to his delight, had trapped him in a closet the previous day. Above all, Schulz is gripped by a capitalized and personified Fear that “soon, very soon indeed, something unimaginably dreadful was going to happen.” Indeed, the novella ends with Schulz stepping out on the street, seeing

a blaze of red firelight over the nocturnal city, [hearing] the sound of motor engines and loud orders, and when he looked to left or right he always saw, at the end of every alley, a gigantic, black, prehistoric insect running past on feet that rattled like tank tracks . . . the doves in the sky above Drohobycz flew one after another into the red firelight, where they burned like tinder.

Shulz really did write a letter to Thomas Mann to ask for assistance in getting published in German. In Biller’s novella the letter becomes a stifled cry for help on the eve of the catastrophe—and it remains unanswered. Biller has written about Mann at length elsewhere. In fact, he wrote at university on Mann and Jews. To Biller, Mann represents the lie of the “noble German,” and his literary sainthood is just another example of Germany’s rotten culture. Mann’s attitude toward his Jewish characters—the evil family Hagenström in Buddenbrooks, the devil manifesting himself as the proto-fascist Chaim Breisacher in Doktor Faustus—had anti-Semitic undertones.

(Courtesy of Yad Vashem Art Museum.)

It seems that to Biller, the Shoah is basically a conflict of aesthetics. Biller is a firm believer in the Jew as the essential outsider, an emblem and fetish for Germans scared of individuality. He is historically aware enough to know that German Jews didn’t necessarily see themselves that way. Many really did see themselves as “Germans of Mosaic faith.” And they loved Mann. For better or worse, Biller calls on Bruno Schulz as a stand-in for the pitiable German Jew who foolishly believes in German culture. Of course, this couldn’t be further from the biographical reality of Schulz, a Polish-speaking Jew who missed Galicia and just happened to like Thomas Mann. (So, for that matter, did the Yiddish writer Der Nister, who modeled his magnum opus Di Mishpokhe Mashber in part on Mann’s Buddenbrooks.)

In actually trying to depict Schulz’s complicated world, Biller stumbles. For every vivid detail—like Schulz’s preferred brand of pencil—there is a wrong note. Schulz tells two bothersome schoolboys to leave him alone and “think of something nice, like what presents you would like for Chanukah”—an American custom scarcely known amongst Polish Jews in 1938. Biller also has Schulz mention the “Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov,” who would not assume that position until 1939. These are minor slips, yet they betray an awkwardness around the historical subject at hand that is at odds with the grandiose claim of Biller’s title.

In fact, his attempt to look inside Schulz falls similarly flat. The big mystery of Schulz’s life is why he didn’t leave Drohobycz when he had the chance. Biller finds the answer in what he thinks is Schulz’s masochism. His last infernal vision is paired with his wish to be tied up and beaten by his co-teacher Helena. In the end, the poetic longing in Schulz’s stories, according to Biller, is no more than the desire to be whipped and chained.

Biller has made it clear that he doesn’t want to follow the prewar German-Jewish literary tradition, and that he is also not interested in making his work palatable for a non-Jewish German audience—an audience that has sometimes received his work with subdued hostility for its perceived overemphasis on Jewish topics and on Jewishness itself.

This actually serves Biller well. He sees himself as part of a lineage that includes Isaac Babel, Danilo Kiš, and indeed Bruno Schulz—outsiders who were truly appreciated only after their death. At the same time there is undeniable melancholy. “A pleasant shiver ran through me as I imagined that I would speak the same clear New York English [sic] today had my parents emigrated to America instead of Germany,” writes Biller about his encounter with the American critic Daniel Mendelsohn. “Going to New York” appears as a motif time and again.

And yet Biller has failed to win over English readers. He has not become a Sebald, or even a Daniel Kehlmann. His excellent translator Anthea Bell is not to blame. Her work here accurately reflects Biller’s attempt to broaden his style to incorporate Schulz’s overwhelming sense of color and mood.

Biller’s literary affinities do make him unique among German writers, both Jewish and non-Jewish. But read in the context of non-German Jewish writing—the context in which he sees himself—he is up against Dara Horn and Nathan Englander, to name just two peers who are also in constant dialogue with Jewish history and literature, and who deepen our understanding of the works and writers upon whom they build.

Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz fails as both introduction and homage. By offering a crude mixture of sexual neurosis and Jewish anxiety, Biller ultimately cheapens Schulz’s work and almost robs it of its mystery. But only almost, for Schulz’s stories are too strange and strong. They will always be able to stand on their own. The same cannot be said for Biller’s strangely perfunctory novella.

Suggested Reading

A Stolen Seat

“Good Shabbos—you’re sitting in my seat” takes on a whole new meaning when it’s your brother- in-law talking. From a Russian Jewish diary, with an introduction by Alice Nakhimovsky and Michael Beizer.

Heschel Transcendent

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s intellectual peers included Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His main thought, Shai Held argues, was of transcendence.

Old-New Sabbath

Does everyone need a Sabbath? Judith Shulevitz thinks so.

When Canines Were in the Land

Did dogs save the Jewish State?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In