A Season of Tzuris: The Shtisels Return

It has been five long years since we last saw the Shtisels. While Israeli viewers just finished the nine episodes of season 3, Americans had to wait until today to see it on Netflix. Internecine politics, disasters natural and human, and a once-in-a-century pandemic have visited our world in the intervening half-decade. Things haven’t been easy for the Shtisels either.

When the show’s third season begins, one of the young couples in this large extended family silently suffers from infertility, while another pair has been rent asunder by the angel of death. Meanwhile, the once prosperous Belgian uncle Nuchem (Sasson Gabai) has taken to sleeping on the hard wooden benches of a local shtiebel. Even the dogged family patriarch, Reb Shulem Shtisel (Doval’e Glickman), now walks with a cane, on which he hobbles right into a career-ending incident at the cheder he runs. When Shulem receives a desperate phone call with another piece of bad news, he sighs and says, “Master of the Universe! What do you want from your yiddelech?!” It is a cry that will resonate with its audience, though few of them express their pain in Shulem’s signature mixture of Hebrew and Yiddish (and many of them are not Jewish).

Shtisel’s unlikely international success is built on audiences drawn to the struggles of this relatable family despite—though on second thought, also because—of their radical difference. If only for a moment, we forget our troubles when we watch this “unhappy family . . . unhappy in its own way”—not just in the fact of their unhappiness but in their distinctive haredi lives. Much has been made of the tremendous lengths the Shtisel crew went to re-create the self-enclosed universe of the Geula neighborhood, populated by “Yerushalmim,” a unique Jerusalemite amalgam of Hasidic and misnagdic cultures. The production crew included experts to help the non-Yiddish-speaking actors get the language and lilt just right, as well as mashgichim (supervisors) to ensure that both Jewish law and custom were scrupulously portrayed. The arduous work of accurately depicting this subculture of a subculture (which is playfully acknowledged in a subplot that has Zohar Strauss’s ever-scheming Lipa start a business supplying ultra-Orthodox extras to a film crew) is not just about realism. Rather, it is because, as I argued in my review of the first two seasons, the ritualistic obsessions of haredi life offer the filmmaker an ideal symbolically dense palette with which to capture the extraordinary struggles of ordinary life.

In season 3, the Shtisels reckon with an endless procession of trials and tribulations, from the perils of courtship to the strains of fraying marriages. There is alcoholism, loss of work and dignity, mental illness—including an attempted suicide—and other life-threatening conditions. At one point, child services is called in. As in prior seasons, in which the family mourns the loss of its matriarch, Dvorah, loss and the literal specter of loss hovers above the action. Yet, despite the anguish, it would be inaccurate to describe the Shtisel family as an unrelievedly unhappy family. They have their coping mechanisms and small pleasures, both of them often culturally specific.

Wit and humor, both light and black, do more than dull the pain; they transform, if fleetingly, calamity into comedy. Akiva finds relief with a pair of haredi misfits, one of whom is identified only by his nickname, Fershluffen—meaning something like “sleepy” in Yiddish. In a politically charged vignette, one of the Shtisel balabustasrelies on her impressive strength and wit to overcome the patriarchal conviction that women should not drive, ensuring that in the end—mini spoiler alert—she wins the peppy neon-green Fiat of her dreams. In the season’s most superbly acted scene, Shulem faces down three haredi men issuing a summons to rabbinic court. Incensed, Shulem fumes, saying, “What do you think I am, some mizrochnik—some religious Zionist—sitting in a booth selling lotto tickets?!” The non sequitur is utterly senseless outside the hall of mirrors of Shulem’s mind (and the memory of the audience, who will remember the sad story of Sucher, Shulem’s brother-in-law), and so we laugh at, but also with, Shulem at the moment of his unraveling.

There are also many expressions of communal compassion that address the characters’ pain head-on. Among many things, the haredi community is famous for its formal and informal charitable associations, known by the Hebrew acronym GeMaCH’s (for gemilus chassodim, acts of loving-kindness). Giti (Neta Riskin), the head of the family restaurant, runs out one afternoon to deliver tins of food to someone who is af tzuris (roughly, beset by troubles). Less visible, but just as affecting, are intimate moments of pious, even radical, kindness. In a beautiful retelling of an old Jewish tale, a poor couple subtly deceive one another to each discreetly take up a side gig—as it turns out the same side gig—delivering mail in the predawn hours. A major plot turn, which I will not spoil, has a character willing to dramatically reorient her life to save someone she hardly knows. Even the simple way Shulem beseeches his guests to let him give them a glass of soda with a little shpritz of flavor gestures toward the redemptive power of quiet kindness.

If we were to ask the Shtisels what gets them through all the tzuris, they would undoubtedly respond that it is the study of Torah. Two members of the Shtisel clan, Zvi Arye (Sarel Piterman) and Hanina Tonik (Yoav Rotman), spend their lives studying in kollel. A grandson, Yosa’le Weiss (Gal Fishel), has to be persuaded to leave the study hall to start dating for marriage—if it were up to him, he would spend his days with nur Toyreh (only Torah). The Shtisel women have made tremendous sacrifices to this scholars’ economy, working as the primary breadwinners so that their husbands can occupy themselves in the dizzying dialectics of Talmud. Remarkably (and, apparently, realistically), they seem to be largely happy with this arrangement.

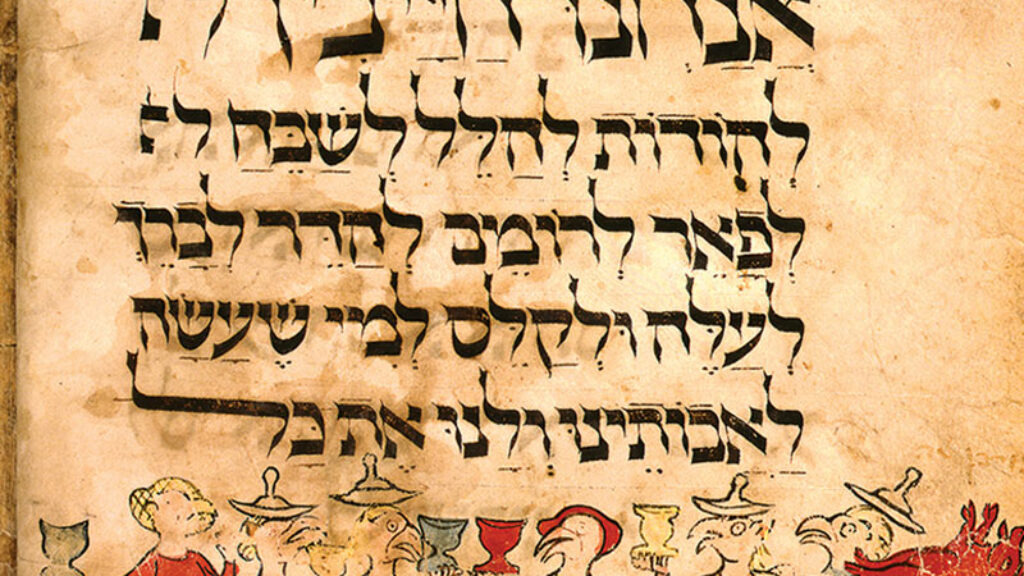

The ever-present din of religious study in Shtisel is more than another example of the show’s sensitive realism. When Shulem tries to regain control of his classroom in the cheder, he recalls Abraham bargaining with God to save the city from destruction (Genesis 18), even for just “one righteous man of Sodom.” The allusions pile up, and Shulem frequently abbreviates with a tired “ve-chu”(etc.), encouraging his listeners to complete the reference on their own. A little like Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye, Shulem also sometimes botches the references, perhaps a sign of his aging or just his humanity. Regardless, such allusions reveal the comforting intertextual fabric of haredi life.

And yet, the writing goes much further than a verse here and a midrash there. In the first season, it was already clear that the show’s creators, Ori Elon and Yehonatan Indursky, would redeploy their advanced Talmud educations in more interesting ways. There was, for instance, the episode in which we hear a rapid-fire talmudic discourse about a ship docked on the Sabbath within the ritual perimeter of a city. In this latest season, many of the overheard talmudic discussions are just as complex, and they add further layers to the story. Now a widower of seven years, Shulem spends much of his time alone at the dining room table, smoking and learning out loud passages like Berachot 5b, which explores the disturbing theodicy of so-called yissurin shel ahava (the “sufferings of love” that God inflicts upon the pious).

On their anniversary, Hanina, the show’s most dedicated yeshiva student, offers his young wife, Ruchama (Shira Haas, whose piety here may startle some viewers who now know her as the star of Unorthodox), an intricate homily that weaves together sources such as the halakhic discussion of rescuing someone buried in rubble (Mishnah Yoma 8:7) and Jacob’s romantic removal of the well’s covering when he first meets Rachel (Genesis 29). He writes it out on a piece of thick paper like a love poem, but it can’t solve their terrible predicament. And yet, when matters come to a head in a later episode and Hanina asks the head of his yeshiva dean for an expert opinion on what to do about his marriage, he is encouraged to decide for himself after first spending an hour or two immersed in Talmud study. As if by chance, the passage Hanina ends up studying is Shabbat 32a, whose strange and startling teaching about the power of grace against impossible odds—“Even if there are nine hundred ninety-nine portions within the angel accusing him, and one portion asserting innocence, he is saved”—cries out to him like an oracle. Magically, the Talmud provides the counsel Hanina sought and serves as a reminder that his beloved Ruchama is, if not literally one in a million, at least one in a thousand.

Shtisel’s creative reappropriation of classical Jewish texts is perhaps its most remarkable feat: Elon and Indursky have followed the artistic lead of great Hebrew modernists like S. Y. Agnon and Yehuda Amichai to write a TV show. And now it is being watched by international audiences who cannot possibly get all, or even most, of the references (in truth, neither can most viewers in Tel Aviv). And yet, that does not mean that the echoes and allusions are entirely lost on them. What they have responded to, I think, is a sense of cultural depth and the deep truth that the greatest expressions of art and life are almost always elaborate re-creations of earlier wisdom.

In the season’s penultimate scene, Shulem asks Nukhem and Akiva—and us—to share a final glass of seltzer with him. He is struggling to remember a reference by a certain koyfer (heretic), the Yiddish author, Isaac Bashevis Singer, whose work he “chanced upon” in the bathroom (the only appropriate place to read secular books). When someone finally recalls the correct name of the author, Shulem relates his teaching (from the novel Shosha)that all of us are walking graveyards, carrying within us our bubbesand zeides. The deadare always with us. As the camera pulls back, we see and hear the room crowded with Shulem’s dead: his beloved wife, Dvorah; his mother and mother-in-law; grandparents; and more, serving and eating food, sitting together, and kibbitzing.

As the ancient rabbis said, when we invoke the teachings of the dead, their lips mouth the words in the grave.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Our Lady in Tehran

In Tehran, the Mossad has orchestrated a complex and brazen operation as part of a last-ditch effort to cut the capital’s power supply so that the Israeli Air Force can take out Iran’s nuclear program

No Sex in the City: On Srugim

A new Israeli TV show chronicles single life in Jerusalem.

Holiness and Public Policy: The Haredi Response to COVID-19

Bnei Brak, where yeshivot and synagogues were kept open far too long, accounted for 16 percent of all Israeli COVID-19 cases and a comparable percentage of fatalities despite comprising only 2 percent of the Israeli population. We haredim must radically rethink our approach to public policy—and holiness.

(Almost) People

What does it mean to say that books have lives?

Jonathan Gerard

This review, without warning, gives away important plot events in the first episode of season 3 of Shtisel before the first airing of the program on Netflix. I am very annoyed. Publishing this was inexcusable.