After the Fall

The antigovernment demonstrations continue. So does Israel’s freefall. As I write these words in the second half of August, there is disarray in the command echelons of the country’s air force, the mainstay of its military might, caused by protesting reserve officers who are refusing to report for duty. One grimly imagines a meeting of the joint chiefs of staff of Iran and Hezbollah, which has been preparing for war with Israel for years. “Let’s strike now before the Israelis get their act back together,” urges one general. “On the contrary,” says another, “the longer we wait, the more they’ll unravel.”

Who would have believed things could fall apart so quickly? When I wrote in these pages last December, well before the formation of the coalition government that emerged from November’s elections, that Israel had “fallen from a cliff” and that no one could say when it would hit bottom, many readers, even those as appalled by the government-elect as I was, thought I was exaggerating greatly. I dare say no one still thinks that.

There is no consolation in this or in having one’s fears borne out by Benjamin Netanyahu’s clerical-nationalist coalition, the havoc wreaked by which has gone well beyond its so-called judicial reform plan. The Netanyahu government has ignored pressing national problems; squandered huge sums on sectarian-religious interests; shown contempt for Israel’s Arab population and done nothing to combat its shocking homicide rate, driven by unchecked crime wars; turned a blind eye to pogroms and settler violence against Palestinians in the territories while contributing to a surge in Palestinian terror by deliberately weakening a Palestinian Authority that had helped to control it; and degraded public life by staffing high offices with cronies, handing out jobs and contracts as political plums, and behaving as Tammany Hall might have done had it had a country rather than a city to rule. It would get a first-semester report card full of Fs, even had judicial reform never existed.

And yet I am in a way more hopeful now than I was in December.

Back then, shortly after the elections, the half of Israel that had voted for the losing parties was in a state of shock and paralysis. There was a sense of helplessness that I shared, a feeling that there was nothing to be done, that a macabre constellation of forces had come to power and would have its way.

The first protest demonstration had yet to take place. And it was only when it did, on January 14, in what has entered Israeli lore as “the protest of the umbrellas”—because a crowd of eighty thousand turned out in a pouring Saturday night rain in Tel Aviv to tell the new government that it would be resisted—that the paralysis passed. Suddenly, there were demonstrations everywhere: week after week, Saturday night after Saturday night, often on weekdays too; the biggest in Tel Aviv but also in cities and towns all over the country—100,000 demonstrators, 150,000, 200,000. Masses of Israelis had woken from what seemed a bad dream to find that it was not a dream at all but that they had the power to act that dreamers do not have.

They have been remarkable, these demonstrations. They have been large and noisy but rarely unruly and never violent (though the tactical wisdom of some demonstrators in blocking highways and airport access or staging protests outside private homes can be debated). They have expressed anger and frustration but more good cheer than anger and more determination than frustration. They have been marked by a sense of standing together, of those beside you being there for you as you are there for them. The Israeli flags that most of the demonstrators hold and wave are not a PR stunt. They say what those holding them feel: “This is our country. It will not be taken from us.”

The demonstrators are all ages. One sees grandparents, parents, and children side by side. Nearly all belong to what can be called secular Israel, keeping in mind that many secular Israelis observe some Jewish rituals in their homes; kippot and other signs of strict religious observance are rare. Few of the protesters have been involved in political activity before. They are not demonstrating for a cause or ideology. They have turned out week after week because they fear that the alliance of an indicted prime minister, brainless and spineless politicians, fundamentalist rabbis, Land of Israel zealots, and Kahanist

xenophobes that is now running the country they live in and love will make it unlivable.

And they have succeeded. When Justice Minister Yariv Levin presented his judicial reform plan to the Knesset on January 4, it contained four main planks: the abolition of the courts’ right to strike down legislation or executive action as “unreasonable”; an “override clause” that would empower the Knesset to reverse court decisions by a simple majority vote; a change in the composition of Israel’s Judicial Selection Committee that would give the elected government control of the appointment of all judges; and the demotion of the attorney general’s office to a merely advisory body whose representatives could be fired at will and whose legal opinions, hitherto binding on the government’s ministries, could be freely ignored. These measures would have allowed the Knesset and government to pass any law and issue any edict without effective judicial review or restraint, and ultimately, to pack the courts with subservient judges, as has been done in once-democratic countries such as Poland and Hungary.

It has been argued by proponents of the reforms that they are less drastic than claimed and are needed to correct imbalances created by an activist High Court that has for years exceeded its legitimate mandate. There is something to be said for this. Israel’s High Court has indeed allowed itself to rule on issues that do not generally reach other such courts and to judge them by standards that few other courts would apply. Although the High Court has sometimes been drawn into vacuums created by government or Knesset inaction, it is admittedly problematic when, say, a court decides that a democratically elected government has behaved “unreasonably” rather than illegally. Yet is it any less problematic when a democratically elected government regularly flouts democratic norms by such acts as appointing a twice-convicted felon as its minister of the interior or an outspoken racist with a long record of inciting and defending violence to head its ministry in charge of the police? Does not the public need to be protected, whether by the courts or ministerial legal advisers with real powers, from a government like Benjamin Netanyahu’s, even if it has elected it?

In the end, the Netanyahu government backed down from its original plan to ram Levin’s entire package of reforms through the Knesset by the end of the latter’s summer session and put only one of its proposals, revocation of the “reasonableness” criterion, up for a vote—and even that was approved in a watered-down version that applies to the decisions of cabinet ministers alone and not, as originally planned, to those of lesser officials as well. This retreat was due to the demonstrators.

Not just due to them, of course. Viewed narrowly, it was not due to them at all, since what caused the government to backpedal were other things: the threat of striking reservists; warnings by Israel’s business elite of a severe economic downturn; a flight of capital from the country; a consequent plunge in the value of the shekel; the beginnings of a relocation abroad of Israel’s vaunted high-tech sector; a possible downgrade of its credit rating; the worried reaction of foreign countries, particularly the United States; and public opinion polls showing part of the coalition’s Likud electoral base turning against it. Netanyahu and his partners could put on a brave face and declare that all this would pass once it was realized that they meant to stand their ground, but they were scared by it and rightly so.

None of this would have happened, however, without the protest movement. A striking pilot needs public support just as he needs a wingman in a dogfight, and no Israeli businessmen would have questioned the future health of a strong economy were it not imperiled by civil disorder, nor would the U.S. government have been worried by an internal Israeli matter that did not worry Israelis themselves. Had not so many of them taken to the streets, every one of Levin’s reforms would have been adopted.

Were the demonstrators justified in bringing Israel to such a pass? That depends, of course, on one’s assessment of the Netanyahu government’s intentions. Only if one believed that they posed a clear and present danger to democracy could one defend jeopardizing Israel’s economy and military preparedness to prevent this. The precedent of reservists refusing to serve is especially troubling. Turnabout is fair play: should a future government of the Center-Left ever wish to evacuate settlements, as did the government of Ariel Sharon in 2005, or negotiate the establishment of a Palestinian state, as did the government of Ehud Olmert in 2009, by what logic will the supporters of the striking soldiers of 2023 seek to dissuade the striking soldiers of 2028?

This is a grave question. But a more timely one might be: even if Israel’s courts deserved to have their powers trimmed, and even if the government’s motive for trimming them was not, as the opposition to the judicial reforms feared, to impose semiauthoritarian rule, why did it not, when confronted with this fear, suspend further action at once? Netanyahu or Levin could have said something like: “Look, we think your apprehensions are absurd. But since they are real, and since none of the proposed reforms, which come to correct long-standing inequities, is a matter of special urgency, we will not tear the country apart over them. Let them be subject to a dispassionate and, if necessary, prolonged national debate before we go ahead with them. In the best of cases, a consensus may be reached. In the worst, we will not have acted rashly. There are enough other concerns to keep us occupied in the meantime: Iran, Hezbollah, Israel’s exorbitant cost of living, its housing crisis, its floundering educational and medical systems, its clogged roads—the list is long. Let’s get to work on it.”

The Netanyahu government could have done this. Few Likud voters in November’s election, in which judicial reform was a rarely mentioned issue, cared about it much or at all; probably not one in ten would have put it high on a list of priorities. The Likud’s coalition partners had more of a stake in it: theultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism and Shas parties because they wanted haredi yeshiva students to be exempted by law from all army service (something past High Court decisions had stood in the way of), and the hypernationalist Religious Zionism and Jewish Power parties to keep the court from interfering in the expansion of settlements on Palestinian land and discriminatory practices against Israeli Arabs. But these parties needed Netanyahu as much as he needed them; there was no necessity for him to let Levin, a high-ranking Likud member, put judicial reform at the top of the coalition’s legislative agenda to the near exclusion of all else. This only lent credence to the suspicion that the government’s intentions were sinister. For what other end than a fundamental regime change that would ensure its permanent grip on power would it have thought it worth plunging Israel into such chaos? Surely, not just to correct a problem of occasional judicial overreach; surely, too, not to extricate Netanyahu from a trial that had gone too far to be called off. It had to be something else, something more like what hundreds of thousands of demonstrators had in mind when they chanted week after week, “There will be no dictatorship here!”

The demonstrators surprised even themselves. None of them had thought such sustained turnouts were possible. These have made it clear that a large body of Israelis, though politically inactive until now, will not accept the clipping of democracy’s wings. “You’ve tangled with the wrong generation,” nafaltem al ha-dor halo-nakhon, is one of the antigovernment slogans of what is preeminently a multigenerational movement. Although the demonstrations have been superbly organized, the parliamentary Opposition has had almost nothing to do with them. Someone, of course, has had to plan them, get the word out on social media, arrange for speakers and technical equipment, and raise the money to pay for all this, but the organizers have come from the ranks and are not known figures even to most of their fellow protesters.

They have, these protesters, gotten the best of the first round. Why, then, is there such dejection among so many of them? Talk to them and you will hear things like: “We’ve lost.” “It’s hopeless.” “We’ve accomplished nothing.” There is more and more talk of emigration. Conversations turn to green cards, foreign passports, acquiring citizenship in this or that country. “My son will go into the army in three years,” a demonstrating mother said to me. “If this government is still in power then, I’m leaving. I’m not putting his life in its hands.” She had tears in her eyes.

But Netanyahu may remain in power for at least three more years, since the next elections are scheduled for November 2026, and there is nothing right now to make his coalition fall before then, as unpopular as it may be. The more unpopular it becomes, the more its parties will cling to one another to avoid defeat in an early vote.

Still, the three years will pass and the Opposition, if the polls hold steady, will win in 2026. Even before then surprises are possible. Netanyahu may be convicted on two of the three charges against him (an acquittal on the third seems likely), reshuffling the political deck. Or the Biden administration may achieve its ambition of a Saudi-Israeli peace deal whose Israeli concessions to the Palestinians will force the extreme Right out of Netanyahu’s coalition and make room for the Center-Left. What cause is there for such despondency?

A part of it is the protesters’ knowledge that, even if they win, it will take years for Israel to recover from the brutal fall it has taken. A part is Netanyahu himself. The same demonstrators who revile him have an almost superstitious belief in his powers. Time after time, he has bounced back from situations that would have ended the careers of other politicians; time after time, many of the protesters feel sure, he will do it again. Tell them they have bested him and they say, “Don’t you understand that he’ll never give up, that he’ll always have another trick up his sleeve?” Remind them of his promise to seek agreement with the Opposition before pushing through any further reforms, and they shake their heads at your naivete. “When did Netanyahu ever keep a promise?”

For all their determination, many of the demonstrators, especially those more inclined to the Left, have little confidence in their own strength.The Israeli Left is not used to winning. Excluding Centrist candidates supported by it as default choices, it hasn’t won an election since Ehud Barak’s victory in 1998. It hasn’t had a major event to celebrate since Yitzhak Rabin signed the 1993 Oslo Accord, the disastrous outcome of which initiated a long political decline that has left it with a permanent sense of being on the losing side. And in fact, what is happening in Israel now is the Right’s revenge for Oslo, in which it seeks to do what it feels was done to it in 1993, when the Rabin government won the Knesset’s approval for an agreement with Yasser Arafat by the narrowest of margins and against the bitter opposition of half the country. The specter of Oslo and of the Palestinian problem that it failed to solve haunts the demonstrators too. It lies not only behind them but ahead of them. They know that the judicial reform battle, as critical as it may be, is only a dress rehearsal. Even were all the reforms to pass, they would not spell the end of Israel. The Palestinian problem can and quite possibly will.

Wisely, perhaps, the issue of the Palestinians has so far been kept out of the protest as a matter of deliberate policy. The protesters know that to embrace it at this point would cost them part of their public support and fracture their solidarity. Several weeks ago, I took part in a demonstration in my hometown of Zichron Ya’akov, at which, for the first time, there was an Arab speaker from the nearby town of Faradis. He was blunt. “You Jews are fooling yourselves,” he said, “if you think you can have democracy while oppressing us. Either we all live in a free country or none of us does. Let there be democracy for everyone in one land from the Jordan to the sea!”

He was met with a smattering of applause, a heavier chorus of boos, and a still heavier uneasy silence. Nearly all the demonstrators would have told him that the one-state “equality for all” solution advocated by him, even in the improbable eventuality that it could work, was unacceptable to them; they want to live in a Jewish, not a binational, state. But they also knew that a conventional two-state solution has long been impossible, given the massive presence of Israeli settlers in the territories, and that prolongation of a status quo in which millions of Palestinians have no rights is morally indecent and politically unmaintainable, no matter how long it may have lasted until now. Hence, their silence.

It is possible to imagine the judicial reform crisis ending in a parliamentary compromise; conceivably, this could be along the lines suggested, so far unsuccessfully, by Israel’s president Isaac Herzog. Every one of the issues involved has its middle ground. Although such a compromise would leave many of the demonstrators unhappy and feeling betrayed by the parliamentary parties that sign off on it, it is the obvious way out of the impasse.

But where is the middle ground when it comes to the territories and the settlements? Quite apart from the fact that any common position would then have to win the improbable acceptance of the Palestinians, how could such a compromise be reached between two sides over land that one side considers given to it by God and the other does not?

And so even if the demonstrators win the judicial reform battle, they will be like a person who scrambles back up a steep cliff at enormous effort only to face a high mountain that still bars the way to safety. Who wouldn’t feel heavyhearted in their place?

The second round of the judicial reform battle begins in September, when the High Court convenes to hear arguments for and against the Knesset’s repeal of the “reasonableness” criterion. If the court’s decision, which could come as early as October, strikes the Knesset’s legislation down, the government will have three options: to accept the decision; to refuse to accept it, thereby precipitating a showdown with the court; or to do nothing and wait for the criterion to be invoked in a specific case. Meanwhile, on November 15, the Knesset will reconvene for its winter session, at which the first reform to come up will be that of the Judicial Selection Committee. There will be more than enough to keep the demonstrations going.

Even before that, Israel will go to the polls on October 31 in nationwide municipal elections. Such elections, which choose mayors and town councils, are not normally accorded much national significance, since many of their candidates run as independents and local issues predominate. This year, though, the judicial reform battle will inevitably spill over into them. Candidates will be called upon to take a stand on it. For the protest movement, this will be a first test of its ability to translate the energy of the demonstrations into electoral activity. It is one thing to wave a flag in a city square, another to knock on doors, canvas for votes, join or organize political discussion groups in which not everyone shares your view, and get those who share it, or can be gotten to share it, to the polls. These are things that can win or lose elections.

Far more critical, of course, will be the national elections of 2026. Israel can survive, if at great cost, three more years of the present government; yet if the Center-Left does not win in 2026, a dire situation will become desperate. Here, too, the protesters of 2023 will play a role. The present government has politicized them. It has made them aware that politics, however dull or unpleasant, will determine whether they can live their lives where and how they wish to live them. It has led them to the rueful realization that had they been more active in the close elections of last November, a different government might have been chosen.

When Netanyahu, Smotrich, Ben-Gvir, and company are gone, the task will begin of freeing Israel from the Palestinian morass. This will call for combining forces even more powerful than those arrayed against the present government. It will demand even more determination; more imagination; a participation that better reflects the many faces of Israel; and new alliances and coalitions, some across the secular-religious divide. It will not be a healing process, since the healing can only take place afterward, and it will take years of slow, patient work that, if it fails, will do so with fatal consequences for Israel and for all of Jewish history. But if, as one can only hope, it does not fail, many of those at its forefront will be able to say that it started with them on January 14 of this year, on the night of the umbrellas.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On That Distant Day

Benjamin Netanyahu is back in the Prime Minister’s chair, but where are the factions who put him there taking Israel?

Responses to Halkin

Hillel Halkin's article about the future of Israel and Zionism has sparked a tremendous debate. We have curated some of the most interesting and engaging responses.

Solidarity and Democracy

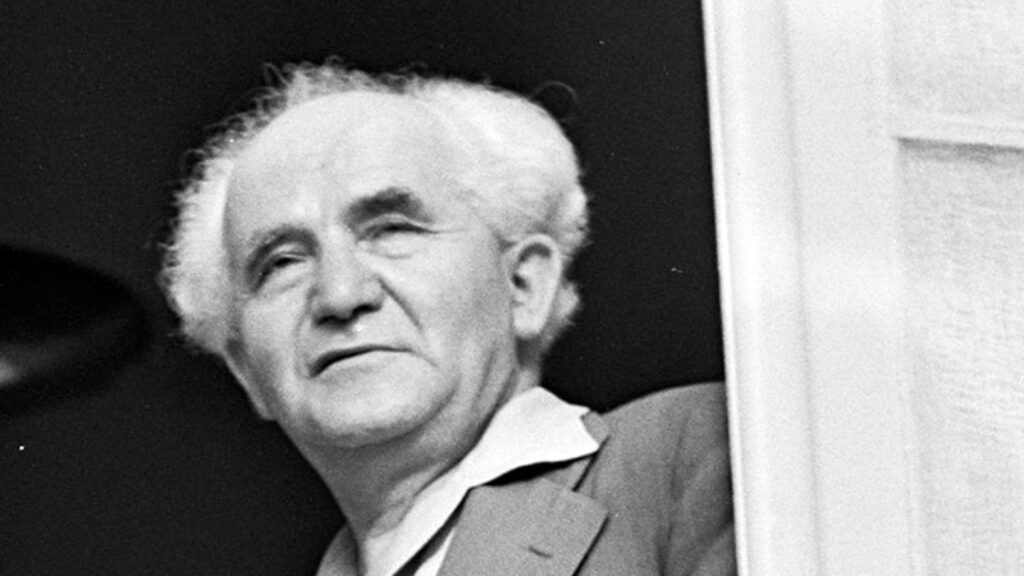

Ben-Gurion saw little need for American-style checks and balances. Instead, he put his democratic faith in mamlakhtiyut.

Wishful Republic

What lessons can be learned from the city of Haifa, and what does its culture suggest about the likelihood and limitations of a binational state?

Jonathan Gerard

This is a pretty good overview of the political landscape in Israel today--worth sharing with more poorly informed friends and neighbors.