This Great House

On October 18, 1899, on the front page of the Warsaw Hebrew daily, Hatzfirah, a physician and book collector named Joseph Chasanowich published a lengthy call to erect a library in Jerusalem:

I say that in Jerusalem there will be built a grand house . . . high and lofty, in which will be gathered all the fruits of Israel’s spirit, from the moment it became a nation. All the books written in Hebrew, and all the books in all the languages that discuss Jews and their teachings, all the writings and the paintings that touch upon their lives. Everything, everything, will be collected in this great house.

When Chasanowich made his emphatic appeal, he had already assembled a large collection of Judaica in Jerusalem counting over fifteen thousand books—more volumes than Jews who were then living in the city. But Chasanowich was ambitious, and he envisioned something larger, more impressive, and comprehensive. A fervent Zionist living in a Zionist age, what Chasanowich willed was no fairy tale. Within six years, the Seventh Zionist Congress began to transform his collection into the main library for the burgeoning Jewish community in Palestine. A decade and a half later, Samuel Hugo Bergmann—professor, philosopher, close friend of Franz Kafka—became the library’s first academic director. And five years after that, the institution merged with the Zionists’ major institution of higher learning, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

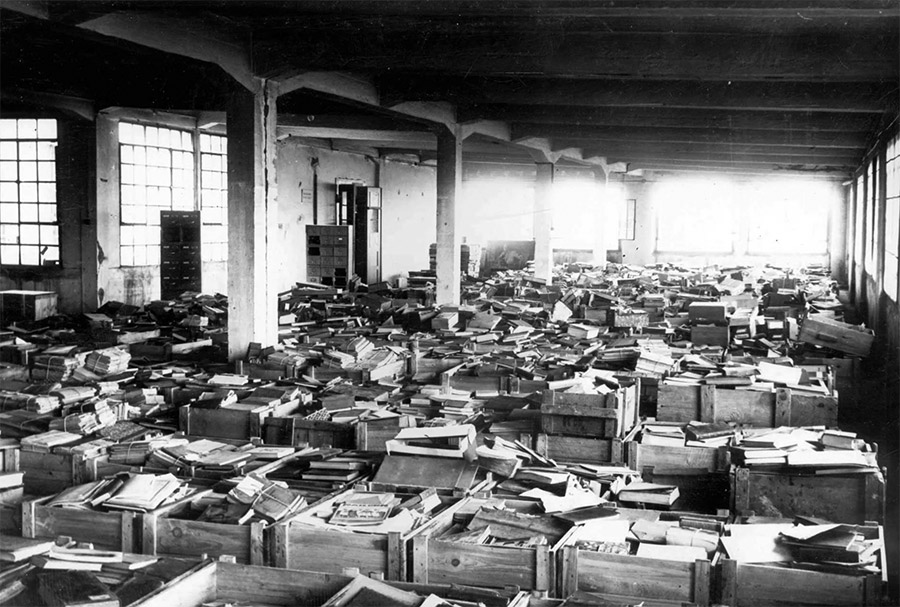

War has shaped the library’s history. Many thousands of books were smuggled to the library in advance of the Shoah, and others were recovered after 1945 by distinguished scholars, including Salo Baron, Hannah Arendt, and Gershom Scholem. Controversially, in 1948 valuable books and manuscripts were salvaged from Palestinian homes abandoned in Western Jerusalem and Haifa and deposited in the library under the auspices of the Custodian for Absentee Property. Of course, it was the 1948 war that led to the establishment of the State of Israel and what was now its official national library. The postwar cease-fire lines presented a logistical nightmare, since the library was then located on Hebrew University’s Mount Scopus campus—an Israeli enclave in Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem. Israeli soldiers stationed on Mount Scopus ferried books to temporary library facilities in the western part of the city (they also sometimes used researchers’ carefully compiled index cards to roll cigarettes). The situation was only remedied after the Six-Day War, when East and West Jerusalem were reunited and the rest of the books could be transferred to the library’s new location, built in 1960, on Hebrew University’s

Givat Ram campus.

The bloody attack unleashed by Hamas on Southern Israel last October delayed the much-anticipated inauguration of the National Library’s new home, also in Givat Ram but now closer to the Israel Museum, Knesset, and other official buildings. As with museum artifacts, the most valuable items in the collections were sent deep into protective vaults. And the grand opening, which was supposed to have taken place right after Sukkot, was postponed. When the library finally opened its doors to the public at the end of the month, it was with little fanfare.

I entered uneasily, thinking of friends and family valiantly serving in uniform and the hostages held in Gaza, in whose honor an exhibit of their beloved books had been quickly assembled. Against good sense, I could not help but recall the response, attributed to an Oxford don during the First World War, about why he was not fighting for civilization on the front lines: “I am civilization!” It’s an insufferable retort, yet not entirely off the mark when it comes to the National Library’s position in the current crisis. As soldiers fight to protect the Jewish state, the library preserves books, documents, and objects covering Israeli and Zionist history and millennia of Jewish writing (it also holds major collections of Islamic and Arabic studies). Indeed, the National Library of Israel aspires to house no less than the bibliographic life of Jewish and Israeli civilization.

A new permanent exhibition at at the library, entitled A Treasury of Words, showcases some of the collections’ most remarkable holdings. It is located in a part of the building dedicated to nonresearchers, where its neighbors are an education center, experiential center, and a nicely appointed gift shop. The William Davidson Permanent Exhibition Gallery, which houses the exhibit, is high-end and high-tech. At the entrance is a sleek, flashing display case containing a sizable set of Aramaic incantation bowls. These unusual artifacts, written in the same dialect of Aramaic as the one used in the Babylonian Talmud, were once buried as talismans in the corners of homes in late antique Iraq. Now they watch over the exhibition, with their inscribed and illustrated innards exposed to viewers for inspection and admiration.

Across the well-spaced room are many glimmering riches, including the famous and gorgeous Rothschild Haggadah; a page of Maimonides’s Judeo-Arabic commentary on the Mishnah in the author’s own hand; a petite, millennium-old Qur’an; an even older Syriac translation of the Bible; and more. At the back of the hall is an enormous rotating electronic display table, the kind of apparatus found in world-class institutions like the Neues Museum in Berlin, which allows viewers to press a button and call up valuable and vulnerable artifacts for temporary viewing. Visitors can gaze at Modern Hebrew literary treasures, such as the corrected galleys to an S.Y. Agnon masterpiece or the working notes of an experimental novel by A.B. Yehoshua, amid an array of Israeli artifacts, like scores to songs written by beloved Israeli songwriter Naomi Shemer and a letter sent by the ill-fated Israeli astronaut Ilan Ramon to the Israeli philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz.

A thick, lavishly made coffee-table book, 101 Treasures from the National Library of Israel is more inclusive than the exhibition. Following laudatory greetings from the president of Israel, the chairman of the library, and the library’s president is a detailed history of the institution. The main body of the volume consists of stunning photography and accompanying essays about the 101 treasures. These are organized into ten themes, with predictable groupings (“Community” and “Canon”), more evocative categories (“Crossing Cultures” and “Journeys”), and thought-provoking sections (“Art and Text” and “Text and Power”). Diving into each is like requesting a unique item from special collections and then enjoying a mini-lecture by the presiding archivist.

A few of the entries in 101 Treasures present artifacts displayed in A Treasury of Words, such as a stunning fourteenth-century illuminated Spanish manuscript of Maimonides’s Code and the thirteenth-century Worms Mahzor, which preserves the earliest example of written Yiddish (“Gut taq im betage se vaer dis mahsor in beis hakeneses trage”—“let a good day shine for he who carries this mahzor to the synagogue!”). 101 Treasures also presents plenty of less flashy but no less crucial items, like Gershom Scholem’s index cards painstakingly documenting the Zohar’s Aramaic terminology; a nearly one-hundred-year-old archive of metal records recording the sounds of Mandatory Palestine; and remnants of libraries lost and found, including the lending library of the Vilna Ghetto and the Offenbach Archival Depot, where some two million Nazi-looted books were gathered by the US Army after the war’s end.

Especially notable are entries that reflect the library’s unrelenting acquisitions ambition. Perhaps most controversial among these is the Kafka archive, which was recently won in an epic court battle. The argument that the Israeli lawyers made is as straightforward as it is self-assured: “Like many other Jews who contributed to western civilization, we think his legacy . . . [and] his manuscripts should be placed here in the Jewish state.” (See “Lost from the Start: Kafka on Spinoza Street” by Stuart Schoffman on Benjamin Balint’s book Kafka’s Last Trial, Fall 2018.)

Both 101 Treasures and A Treasury of Words operate according to the logic of a national museum, preserving an impressive, but still merely representative, sample of the country’s cultural heritage. They are beautiful but necessarily incomplete maps to an irreducible and fantastic place, not the territory itself. Really, they are invitations to visit the library, lose oneself in texts in its reading rooms, wander in its stacks, and bask in its herculean efforts to fulfill Chasanowich’s vision to “gather all the fruits of Israel’s spirit, from the moment it became a nation.”

In James Joyce’s Ulysses, Leopold Bloom walks across Dublin, past the National Museum, and toward the museum’s architectural twin, the National Library of Ireland, “his eyes beating looked steadfastly at cream curves of stone.” To get to the National Library of Israel, one enters Jerusalem, passes the Chords Bridge (another recent project that has redefined the city’s skyline), and travels onward to the governmental district where the library is located. The eyes widen at the sight of the curved structure of Jerusalem stone seemingly floating on a glass platform. At night, interior lighting illuminates the facade, upon which are etchings that suggest Paleo-Hebrew letters. Nearby is a marvelous sculpture garden dreamed up by the Israeli artist Micha Ullman that uses sunlight and the play of shadows to enact the mystical Sefer Yetzirah’s elemental understanding of letters of the Hebrew alphabet as the building blocks of creation.

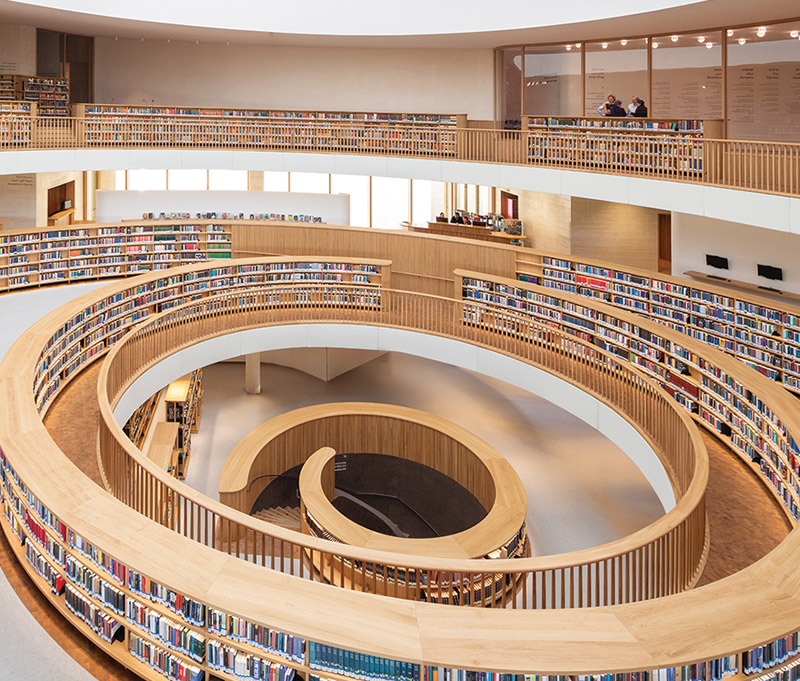

Without exaggeration, the National Library of Israel is the most exquisite building erected in the history of the Jewish state (a leading Swiss firm, Herzog & de Meuron, designed the building). Its gargantuan skylight, bright-green gardens, Negev-toned textiles, and generous windows all reflect recent shifts in Israeli aesthetics. The burning Mediterranean light is no longer an enemy to be shut out by heavy curtains, nor is the building hidden behind high walls. Its tall windows face the boulevard, so that pedestrians walking by can see patrons reading deeply and typing furiously on their laptops. This is all in stark contrast to the bunker-like buildings on the library’s first Mount Scopus campus as well as the library’s second home, which was somewhat unassuming and inaccessibly positioned at the far end of Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus.

Entering the library’s reading halls, one is struck by its open floor plan, which is softened by the strategic placement of staircases and furniture to form separate, cozier reading spaces. There are also two distinct specialized reading rooms: the wood-lined Gershom Scholem library has a muted elegance; the rare-book room, which is designed to look like a jewelry box, is appropriately opulent. The reading room floors almost flow into one another, cascading from the third to the first floor to make it seem as if the library were an undulating fountain of books. I was pleased to find a rounded bookcase shelving numerous volumes of the Talmud and encircling the “pool” at the base. But the real core of the building is below ground level and can be seen, via a large porthole, one floor down. There, one looks in astonishment at apparently endless and impossibly high closed stacks holding most of the more than four million books that make up the library’s collections, preserving them in ideal low-oxygen conditions.

Even as the library constantly expands (as with the Library of Congress, every book published in the country must be officially deposited there), it is committed to keeping the entirety of its holdings on site, making them quickly accessible to patrons. Materials are called up via a sophisticated online system, which dispatches a robot to retrieve the requested items. Remarkably, there is no permanent place for the books in the closed stacks. Each time the robot takes and returns a requested volume, a new location is generated and recorded within the system. “Everything, everything,” Chasanowich wrote, “will be collected in this great house.”

There is something terrifying in the vision of a “universe (which others call the Library)”—that’s the opening phrase of Jorge Luis Borges’s famous story “The Library of Babel.” When a librarian in the Library of Babel grasps that his institution is “total—perfect, complete, and whole, and that its bookshelves contain all possible combinations of the twenty-two orthographic symbols,” it is exhilarating at first but swiftly debilitating. The notion of a library that is “enlightened, solitary, infinite, perfectly unmoving, armed with precious volumes, pointless, incorruptible, and secret,” is awe inspiring. But such a library is closer to the Sefer Yetzirah’s abstract vision of the universe as a set of alphabetic permutations than it is to the library as a human institution, an oasis for book lovers.

As long as I have known it, the National Library of Israel has been such an oasis, not unlike Joyce’s National Library of Ireland: a place of loquacious comradery, where “portals of discovery open” and intellectuals gather to share their latest discoveries, prompting Buck-Mulligan-like cries of “Eureka!” and John Eglintonian trash talk (“You are a delusion. . . . Do you believe your own theory?”). Particularly for Jewish studies scholars, the National Library of Israel has been a bottomless academic watercooler, a ceaseless convivium of striving scholars and idle “hocks” (a Yiddishism for aimless remarks and wild surmises, which punctuate the conversations of Jewish scholars). Sure, it was in the silent reading rooms that giants like David Weiss-Halivni (who sat, like the Eastern European masmid that he was, in the same seat at the front right table whenever he was in Jerusalem) produced work that fundamentally changed the way we read our texts. But it was downstairs, over bad coffee at the pitiful eatery, that academic friends and foes caught up on the latest gossip, planned conferences, plotted job applications, and exchanged ideas, contemplating “possibilities of the possible as possible: things not known.”

In the aughts, when news broke that the National Library of Israel would be relocating, there was an outcry from professors and students, coldhearted philologists and warm-blooded poets. One scholar could be heard repeatedly worrying that a tool critical for his research, the Real-encyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (1890–1980), might be removed from the open stacks. But the real concern underlying all the worry was whether the local genus of scholars would survive the ecological destruction and the move to a new habitat.

More than half a year into a punishing war, the new National Library of Israel is crowded with visitors coming to marvel at its architecture, take in its permanent exhibition, find a quiet place to read, or just achieve some solace. Slowly, the scholarly community has begun to reconstitute itself, securing seats in the nicely appointed reading rooms and conversing over (surprisingly good) coffee in the library’s new cafe. Ultimately, this is what Chasanowich dreamed of 125 years ago—not a collection of books but a people who read them:

To this great house shall stream our masters, sages, and all the scholars of our nation, and everyone with a heart which understands our literature, and whose spirit yearns and strives for the Torah and for wisdom and to know of the history of our people and the lives of our ancestors.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Zero-Sum Game

Most liberal Israelis once believed the 1990s-era Western narrative about Israeli-Palestinian peace: that the Palestinians would eventually be satisfied with a state alongside Israel, that everyone desired the same kind of progress, that maximalist rhetoric on the Arab side masked more modest goals, and that the Palestinian talk about millions of refugees and their “right of return” to Israel was a starting position that was bound to be bargained away.

Culture and Education in the Diaspora

After 1948, Ben-Gurion strongly urged young American Jews to make aliyah. In 1951, Hayim Greenberg, head of the Jewish Agency's Department of Education and Culture, came to Jerusalem to argue for the dignity of Jewish life in the diaspora—in Yiddish.

Tragedy and Power

Barry Gewen’s new book argues that Henry Kissinger's "hardheaded Realism” was born of his family’s tragic experience in Nazi Germany.

Moses Mendelssohn Street

Immortality in Jerusalem.

Janet Rice

Shai Secunda writes in "This Great House" that in 1899, Chasanowich's collection of over 15,000 volumes in Jerusalem exceeded the number of Jews then living in the city. But in Jerusalem: The Biography, Simon Sebag Montefiore says that in 1898 when Kaiser Wilhelm II entered the city, there were 28,000 Jews living there (more than half of the total population). I have just been reading the book, so the difference in the numbers jumped out at me. Wondering if that number was later found to be excessive or if perhaps different city limits are being used by the two writers.