Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and the Halakhot of Hostages: Part II

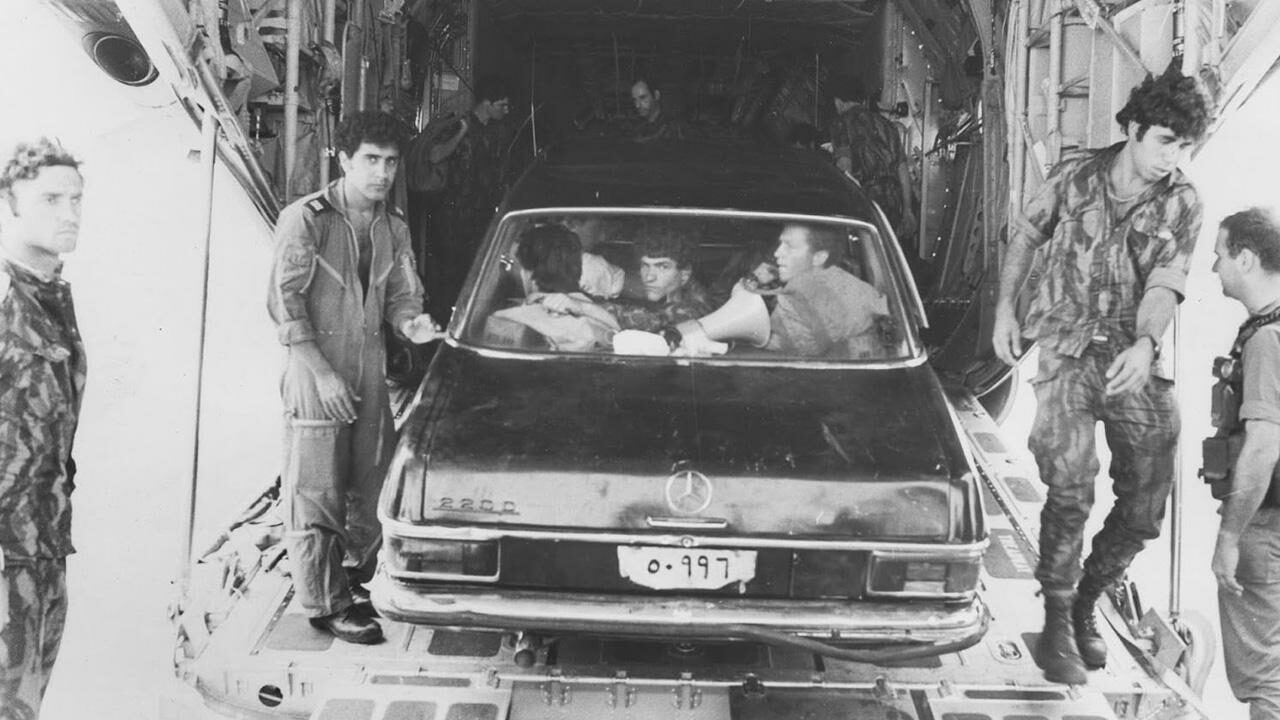

When Chief Rabbi Ovadia Yosef was asked whether one could exchange hostages for imprisoned terrorists in the midst of the Entebbe crisis, he began by arguing that to do so would not violate the prohibition on sacrificing one person in order to save another. We read that even if the released terrorists went on commit further acts of violence, the exchange itself would be an act of rescue, not an act of collaboration with evildoers. We now turn to the next section, which makes up about half of Rabbi Yosef’s long, learned responsum and concerns the duty to save another’s life at risk of one’s own.

The Torah commands, “You shall not stand by the blood of your fellow” (Leviticus 19:16), from which the Rabbis derive that if one sees another “drowning in a river, being dragged away by a wild animal, or under attack by bandits,” he must rescue him (Sanhedrin 73a). These examples seem to indicate that one must take risks—confront bandits and wild animals or jump into a raging river—to try to save someone else. But is the charge not to “stand by the blood of your fellow” absolute, regardless of the risk one incurs, and regardless of the likelihood of a successful rescue?

To answer this question, Rabbi Yosef turned to the thirteenth-century sage Rabbi Meir HaKohen whose work Hagahot Maimoniyot (Glosses to Maimonides) supplemented Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah with rulings from the Ashkenazic tradition, and Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (known as the Radbaz; 1479–1573), who served in the rabbinate in Egypt and the Land of Israel after being expelled from Spain. Hagahot Maimoniyot requires a person to endanger himself to save another based on a passage in the Jerusalem Talmud. Radbaz argues, to the contrary, that someone who risks his life to rescue another is a ‘pious fool’ (hasid shoteh), explaining that “the possible [danger] to himself outweighs the certain [danger] to his companion.” So must one risk his life to save someone else? According to Hagahot Maimoniyot, yes, according to Radbaz, no—in fact, it is forbidden.

However, Rabbi Yosef introduces three key exceptions to Radbaz’s restrictive view: (a) one may risk his life to save a large number of people in danger; (b) one may risk his life to save a great sage or leader, upon whom the community depends; and (c) one may take a minor risk in order to save someone from grave danger. In mentioning this last exception, Rabbi Yosef refers to his own ruling on kidney donation: there is a risk to the donor, but since it is minimal whereas the recipient will almost surely die without a healthy kidney, donation is permitted.

Despite these hedges, Rabbi Yosef concludes in the penultimate paragraph of this section that the question of exchanging dangerous terrorists for the Entebbe hostages would still be a matter of dispute between the opinions of Radbaz and Hagahot Maimoniyot—and that settled halakha follows the opinion of Radbaz:

According to the view of Hagahot Maimoniyot, in the name of the Jerusalem Talmud, that one must incur possible danger to save a companion from certain danger, it seems that in the present case we would have to release the forty terrorists imprisoned here—since even though it might result in their posing renewed danger, it remains uncertain—[in contrast] to saving the abducted Jews from certain danger….

But as a matter of law, we do not follow [the ruling of] Hagahot Maimoniyot. . . rather, we say that uncertain [danger] to oneself overrides certain [danger] to one’s companion, as it says: “Your brother shall live with you” (Leviticus 25:36) [which the Sages in Bava Metzia 62a explain to mean:] your life comes first. And we require that one makes certain to live, as in Yoma (85b), that [the biblical phrase] “and live by them” (Leviticus 18:5) means that one may not put himself in a situation of potential danger.

This would seem to tilt the scales definitively against a prisoner exchange. Halakha follows the view that one may not incur risk to rescue another, so how could Israel risk the lives of its citizens by turning terrorists loose, even to save the lives of hostages? Yet it is at precisely this point in the argument that Rabbi Yosef introduces a further line of inquiry, undermining this conclusion.

Is there, he asks, a difference between endangering oneself to rescue someone and endangering others to rescue someone? Because the exchange of hostages for terrorists is clearly a case of the latter, and the distinction might cut both ways. On the one hand, Hagahot Maimoniyot might require one to incur risk only to oneself but forbid endangering a third party to save another; on the other hand, Radbaz may only prohibit endangering oneself (“your life comes first”) but allow a third party to rescue Person A by placing Person B in some danger.

Rabbi Yosef analyzes this question through the lens of two early modern responsa. In these two cases, saving one person may endanger another. The first incident comes from Responsa Maharival (2:40), by Rabbi Yosef ibn Lev (1505–1580, Turkey and Greece):

Reuven is friendly with the royal advisers and noblemen, and sometimes [the noblemen] would arrest wealthy Jews on behalf of the regime and conscript them…. This Jew [Reuven] is favored by the noblemen and can save a Jew from that misfortune, but he is afraid that if he saves Shimon, they will take Levi in his stead. [But] who is to say that Shimon’s blood is redder? Maybe Levi’s blood is redder! And so he asks whether he is permitted to save Shimon from his troubles.

The second case appears in Beit Hillel (Yoreh Dea 197) the legal commentary of Rabbi Hillel ben Naftali Hertz (1615–1690, Poland and Germany):

I was asked concerning a young woman who was living with her uncle in one community. A gentile libelously accused her of promising to abandon Judaism and to marry him. When her uncle learned that she was thus slandered, he sent her to a different community, governed by a different nobleman. Then, when this gentile saw that she was sent away, he went to the [local] nobleman, who arrested the rabbi and communal leaders, demanding that they bring the young woman before him for trial.

Now, the rabbi and communal leaders wrote to me to extradite the young woman to their city, so that she may stand trial before the nobleman and thus free [the rabbi and communal leaders] from prison. But the young woman cries bitterly that she never spoke even a word of such matters with that gentile.

In both cases, there is an opportunity to free a Jew from prison, sparing them from imminent danger, but to do so endangers others to some extent.

Maharival rules that Reuven may intervene to release Shimon from prison since:

if it is possible that the outrage will pass and no one will be taken in his stead, an uncertainty does not take precedence over something certain. . . . So clearly [such a] rescuer has done nothing wrong and, to the contrary, has done a mitzvah.

In the overall calculus, Reuven has liberated Shimon while only possibly placing Levi at risk. (Maharival does not explicitly invoke Radbaz or Hagahot Maimoniyot, and it is possible that both would agree in this case.)

In the second case, Rabbi Hillel rules that the young woman need not endanger herself to rescue the imprisoned rabbi and leaders because she herself would be in far graver danger than the rabbis and leaders whose freedom she could secure, as only she is accused of breaking the law. The implication is that if the local leaders were in greater danger than the young woman, then the rabbinical court of the community harboring her would have to extradite her to stand trial—possibly according to both Hagahot Maimoniyot and Radbaz.

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef concludes that it is legitimate for a third party to subject one party to moderate risk in order to save another party from mortal danger:

When the choice is given to a third party to decide between two, one who is in a state of possible danger, and the second in certain danger, the possibility [of danger] does not supersede certain [danger], and the rescue of the one in certain danger is given precedence.

In the final paragraph of this section, Rabbi Yosef adds one final argument in favor of exchanging prisoners for hostages:

It seems that we really must be much more concerned about the immediate danger to the hundred abducted Jews, as the cruel terrorist hijackers brandish the sword blade at their heads, threatening to execute them by Thursday, 3 Tammuz [July 1], at 2:00 p.m.—and these evildoers do not make empty threats. But the future risk that the release of forty imprisoned terrorists is liable to pose is not our immediate concern. It is rather a future, long-term concern.

Rabbi Yosef bolsters this argument for the distinction between immediate danger and future danger by citing a rather surprising precedent.

Rabbi Yehezkel Landau, who was the Chief Rabbi of Prague and one of the towering figures of the late eighteenth century, was once posed a question from London. Could surgeons be trained by performing autopsies, which are generally forbidden, on corpses? Rabbi Landau ruled that if a patient was present, and if conducting the autopsy would directly help the performance of the surgery here and now, it was permitted. Under normal circumstances, however, autopsies were forbidden, even though they advanced the medical profession and contributed to the saving of lives in the future. Rabbi Yosef takes Rabbi Landau’s ruling as indication that long-term considerations do not factor into the calculation of risk against rescue.

With these two arguments—that even if one may not put risk his life to save another, one may place a third party at some risk in order to save someone in greater danger, and that indefinite future risk cannot be part of the calculus—Rabbi Yosef concludes, once again, that it is permissible to release terrorists in exchange for hostages.

In the third part of this classic responsum, which I will turn to in the next installment of this series, Rabbi Yosef lays out the parameters of the mitzvah of pidyon shevuyim, the ransoming of captives.

Suggested Reading

Are We All Khazars Now?

While it's exciting to imagine our ancestors as "Jews with swords," the science just isn't there.

Sephardi Soap

With the runaway success of the novel The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem, a television adaptation was all but inevitable, and the decision of Yes Studios to invest record amounts of cash in the show, while eyebrow raising, is also unsurprising.

As Though the Power of Speech Were an Ordinary Matter

Moods provides glimpses into Yoel Hoffmann’s life in literature and his ambivalence about the project of capturing life in words.

Passport Sepharad

The recent offers of citizenship by Spain and Portugal tap into a long, rich, and complicated Sephardi history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In