As Though the Power of Speech Were an Ordinary Matter

At the end of the 24th fragment of Yoel Hoffmann’s latest book, Moods (Matzvei Ru’ach), the following line appears: “We said ‘we need to call the plumber,’ as though the power of speech were an ordinary matter.” The power of speech (ko’ach ha-dibur) is never an ordinary matter in Moods, which is composed of 191 subtly connected fragments and which might just as easily be described as a prose poem as a novel.

Those who have read Hoffmann’s first novel, Bernhard (1989), will recall that it features a plumber who is a poet. It is hard to think of someone better qualified to translate Hoffmann’s oblique investigations into the “power of speech” than Peter Cole, a distinguished poet-translator who translated Hoffmann’s previous three books as well. Hoffmann’s obsession with words—often the names of family members, with their seeming power to raise the dead—must be transformed into English while preserving his strange combination of humor and nostalgia, intimacy and irony. Cole’s sensitive translation allows us to come as close as one can in English to hearing Hoffmann’s words, and this is important for he is as obsessed with the sounds of words as he is with their power. “When a person who doesn’t speak Hebrew hears the word bakhah (wept),” he writes, “he can’t guess what it means.”

Unlike Israel’s other major novelists (Grossman, Oz, Yehoshua), Hoffmann is not a public intellectual. He began his professional life as a professor of Japanese poetry and philosphy, took up fiction in middle age, and has come to be recognized as one of the contemporary masters of Hebrew prose. His sprinkling of Yiddish and German in Hebrew texts that are halfway between poetry and prose, with fragmentary narratives and several levels of metaphor, has led scholars to declare him the herald of a new Israeli postmodernism. Regardless of how accurate (or helpful) this label is, it does hint at the way in which Hoffmann’s novels undermine our expectations of literature, without giving up on the traditional ideals of aesthetic delight or moral investigation.

While his previous novel, Curriculum Vitae, was a kind of account of his life, in 100 fragments, Moods provides glimpses into Hoffmann’s life in literature and his ambivalence about the project of capturing life in words. Early on he writes, “Literature’s so pathetic. We peddle fabric with a sun painted on it and no one even looks up.” Although Hoffmann is now almost 80 (the original Hebrew novel was published in 2010), his speculation that “[t]his might be the last book we’ll write” seems to be as much about the limits of literature as it is about the summing up of a life.

In Moods’ penultimate fragment, Hoffmann writes that he would “like to leave our readers with a great gift before they move on to other books,” a character:

But we’re like a building contractor whose tools are limited . . .

Once we knew a woman whom we could describe (on our own) down to the last of the thousands of hairs on her head. That’s how much care we took with her character. But if we were to do that now, our readers would sue us for excessive particularity. So all we can offer our readers is this: a large mug with the words GOOD MORNING (in English) written across it. They can drink their morning coffee from it and picture a person in their mind’s eye.

What once would have been a meticulous description of character (in Hebrew) becomes a marketing gimmick, empty (English) words that exemplify the limits, even impotence, of the power of speech, in capital letters.

The limitations of speech may also explain Hoffmann’s choice to switch from “I” to “we” in the 14th fragment “out of embarrassment,” he explains. This may have something to do with the famous debate about the importance of the personal voice as opposed to the voice of the national collective in 1960s Israeli literature. Hoffmann’s “we” is neither the homogenizing “we” of early Israeli works, nor the individualist “I” of Natan Zach and his peers; rather, it stands for the fragmentary nature of the self.

Consider again the phrase ko’ach ha-dibur, the power of speech, which may remind the Hebrew reader of ko’ach ha-meshicha, the power of gravity: an irresistible force. The sense of regret, which is so prevalent in Moods, turns this power not into a shared national experience, but rather into an evocation of the experience of personal memory. This is an almost impossible task, even harder in translation, and Cole manages to bring the English reader to Hoffmann’s world of the very local memories from Nahariya, Haifa, Tel Aviv, and Ramat Gan. Cole also manages to reflect, despite the obvious difficulties, Hoffmann’s fascination—evident here perhaps even more than in his previous works—with words and their sounds: onomatopoeias, the foreignness of Hebrew to the ears of newcomers, and the different worlds that different languages build. Here is a typical and beautiful example:

My stepmother Francesca called the ground Boden. The two of us walked across the ground but, because of this other name, it (the ground) carried her differently.

Cole’s elegant translation makes us forget that Hoffmann calls the ground adama and that therefore it carries him “differently” not only compared to his stepmother but also compared to the readers of his novel and perhaps, to some extent, also to Cole himself. These lines also remind us that, at the end, what stands at the center of Hoffmann’s work is the endless attempt to find and represent the way the earth carries its habitats and the experience—our experience—of being thus carried. Toward the end of the book, Hoffmann writes:

There’s someone else we wanted to talk about but we’ve forgotten his name and how he looks. We remember only the other things. That he was a body’s length from the earth’s surface. That he came near and grew distant. That night came over him and the day made him bright, and things of this sort. We can’t recall anyone more precisely. Therefore we miss him, and because we can’t remember his name, our longing is greater than we can say. This person is with us wherever we go, and without him we’d die of a broken heart. And if this seems overly clever to someone, then maybe he should look at himself. This man is also the hero of this book that we’re writing (and of all the books that we’ve written to date). If we could bring him to mind, we wouldn’t need to write.

This abstract figure, whom Hoffmann calls adam, is combined from the many concrete and sometimes real characters (including himself) that populate his works. The word “adam” appears in the original Hebrew version of this paragraph six times, but Cole’s English text uses “someone,” “anyone,” and “this person,” thereby losing something of Hoffmann’s meaning. This “precise figure of a man” (demut ha-adam ha-meduyak) that Hoffmann struggles to recall is not (only) of a specific “someone,” but also the abstract concept of a person—adam—that Hoffmann paradoxically wishes to locate within the rich, diverse experiences of his characters. This may be another reason for Hoffmann’s choice to write most of the novel in the first-person plural. He is writing about himself while attempting to refer to the shared experience of humanity. Perhaps this is also why the word “adama”—earth—is so crucial for Hoffmann, as it includes (in the Hebrew) the word “adam,” and thus the simultaneously personal yet shared experience of human life on earth.

Translation is a difficult art. In his own translation of Japanese haiku and Zen stories, Hoffmann once wrote that “a free translation requires sensitive word choices and placements.” My occasional disagreements notwithstanding, in bringing the Moods of Hoffmann into English, Peter Cole has made masterful choices on every page. One hopes that this will not be Hoffmann’s last book.

Suggested Reading

The Mabam Strategy: Israel, Iran, Syria (and Russia)

In 2017, Israeli fighter jets hit an Iranian weapons facility in Syria, and such strikes have continued over the last 18 months. But as Assad solidifies his victory in the Syrian civil war while Iranian and Russian forces remain on the ground, the next Israeli government must rethink its strategy in “the campaign between the wars,” known in Hebrew as mabam.

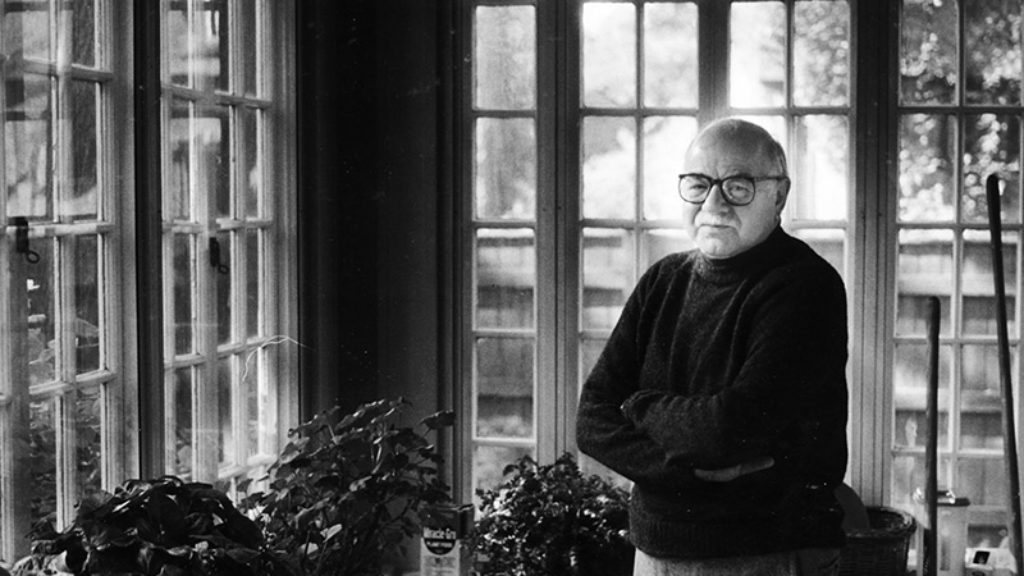

Daniel Bell (1919-2011)

In memoriam.

A Normal Israel?

Zionism has long based its claim to sovereignty on the universal right to national self-determination, and the phrase “like all other nations” has been incorporated into Israel’s Declaration of Independence, yet the goal of “normalization” has proven to be much more complicated than most early Zionists had thought.

Kol Nidre with Dragons

One of the most spectacular books of medieval Ashkenaz, the Leipzig Mahzor, contains a stunning illumination for the opening of Yom Kippur.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In