A Tale of Two Exiles

Not long after Alfred Dreyfus was arrested in 1894 on trumped-up charges of espionage, the notorious French writer and editor Édouard Drumont, called “the pope of antisemitism” by many contemporaries, congratulated himself on his prescience: “Not only did Dreyfus’s treason not surprise me, it seemed to me quite natural. Dreyfus did what Judas did, what Deutz did.” Judas we recognize, but who, most of us would ask, was Deutz, and what exactly did he do?

Readers of the gripping and insightful new book by Maurice Samuels, the director of Yale University’s Program for the Study of Antisemitism and professor of French, will learn the answer—and much more. Simon Deutz was the son of France’s chief rabbi Emmanuel Deutz and, for a time, a close confidant of the mother to a Bourbon pretender to the French throne. He grew up among poor Jews in Paris’s Marais neighborhood and had little chance to become close with his father, who struggled to support his seven children while meeting his community’s needs. Following a troubled childhood, Deutz failed at a host of professions. By his twenties, he was wasting his time in gambling dens and brothels, telling anyone who would listen that “I will either gain a fortune or die trying.”

It was probably this ambition to be rich that led to his shocking decision at age twenty-five to convert to Catholicism. As a prominent rabbi’s son, he was a prized recruit at a time when, as Samuels argues, efforts to convert Jews had taken on a new meaning, serving as evidence of Catholicism’s capacity to resurrect itself after the French Revolution. This was something Deutz understood well. “Son of a rabbi,” he would write later, “I knew my conversion would have a major impact in the Christian world.” In February 1828, he was baptized in the Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome under not only the supervision of a prominent French priest but also—with unmistakable symbolism—the watchful eyes of Michelangelo’s famous sculpture of Moses.

Deutz tried several business ventures in Italy, but all failed, and in 1830 he grasped at the opportunity to set up a Catholic bookstore in New York. It turned out, however, that “there was not much of a market for the highbrow works of theology that Deutz had hoped to sell,” despite the rapidly growing numbers of Irish Catholic immigrants in the city, and he soon recrossed the Atlantic to try his luck in London.

Fifteen years before Deutz’s return to Europe, the Sicilian-born teenage princess, Maria Carolina Luisa di Borbone, stepped into history as the bride of Charles Ferdinand, the duc de Berry, son of the future Charles X, the younger brother and successor of Louis XVIII, the Bourbon king who had assumed power during the monarchical restoration of 1815. Short and nearsighted, with protruding eyes and uneven teeth, the duchess was not beautiful by conventional standards, yet many who met her found her attractive. She was striking for her translucent skin and blond hair, and she would eventually develop a palpable charisma.

On May 30, 1816, Duchess Caroline (as she was now known), covered in diamonds, arrived in Marseille aboard a golden boat rowed by twenty-four sailors wearing white satin, with white flags featuring the fleur-de-lis. Her journey continued with passage through Marseille’s City Hall, where she symbolically bade her governess and childhood friends goodbye. A slow trip through the French countryside to Paris followed, greeting crowds of cheering peasants along the way, followed by her first meeting of her husband in the forest of Fontainebleau.

Four years after her fairy-tale wedding, an assassin murdered her husband, the future king, with a knife outside the Paris Opera. Adding to the young widow’s mystique, she fulfilled the aspirations of the royal family by giving birth seven months later to Ferdinand’s son, who was immediately designated Henry V.

The boy’s royal prospects were shattered in 1830 when France was rocked once more by revolution—the “three glorious days” of July that brought to power Louis-Philippe from the Orleanist branch of the Bourbon family as the “citizen-king.” Yet even as she headed into exile with her son and the rest of the royal family, Duchess Caroline and her fellow “Legitimists” were already seeking a road back to power. This was a role she was well-prepared for. As a member of the royal family in Sicily, she had been forced more than once to flee Naples by the advancing Napoleonic army, and she had “imbibed reactionary royalism and hatred of the French Revolution with her mother’s—or grandmother’s—milk,” Samuels writes, since childhood.

After arriving in England, Caroline and her advisers began to dream of a Bourbon insurrection that would return the family to the throne. By 1831, she was back in her native Italy, trying to turn these fantasies into military-political plans. In her furious correspondence with various coconspirators in France (written in code and often in invisible ink), she received conflicting advice, with many cautioning her against an imminent invasion. Throughout the year, she repeatedly set dates for an invasion and postponed them.

That a misfit convert like Deutz would find his way into the heart of this conspiracy seems extraordinarily unlikely, but Samuels shows how easily it happened. In London, he made a point of going to a French chapel where the Legitimist exiles congregated, praying with such ostentatious fervor, according to Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers, that he attracted the attention of a prominent marquis. The marquis asked him to escort a key general’s wife and daughters to Italy, and soon he was in the presence of the scheming duchess.

After Deutz gained her confidence, she dispatched him on a mission to Dom Miguel I, the king of Portugal, to request help in smuggling a shipment of arms, gunpowder, and cash into France. Deutz would later write that by the time he left the duchess, he had already decided to betray her in defense of the cause of liberty. Samuels, a sober scholar, doubts such retrospective, self-justifying claims from a man as unprincipled as Deutz.

Whatever he may have been planning before the duchess’s ill-fated invasion of France, Deutz was certainly ready to turn against her as soon as the insurrection faltered. After a botched landing in Marseille on April 30, 1832, the duchess proceeded to her movement’s stronghold: the Vendée region of western France. Disguised as a peasant boy and calling herself Petit-Pierre, the duchess led a haphazard military, becoming a modern-day Joan of Arc to her followers. One right-wing journalist wrote that she had a “courage that seduces and subjugates French hearts,” and that if she was “guilty of audacity, of fearlessness, of temerity, these are crimes that will find a great many accomplices in this heroic land.” By mid-June, she was hiding in Nantes, trying to regroup.

Meanwhile, Deutz was on an unsuccessful diplomatic mission in Iberia. When he learned how poorly the insurrection was going, he began to hedge his bets. “There is only one way to deliver France from anarchy and civil war,” he wrote to Louis-Philippe’s government: the arrest of the duchess. Moreover, “there is only one man capable of bringing this about and I am that man.” Nothing came of this, but Deutz wasn’t finished. When he was back in France, in autumn 1832, the regime’s hunt for the duchess had homed in on Nantes but was foundering. Then Adolphe Thiers, an ambitious young lawyer who had played a central role in the 1830 Revolution, was installed as the new interior minister. Believing that the capture of the duchess was essential to quelling resistance in the Vendée, he was only too happy to take help from Deutz—and to offer to pay him half a million francs for it.

When Deutz arrived in Nantes together with Police Commissioner Louis Joly, the duchess had just been persuaded that she should board a ship for Holland or England. It didn’t take long for Deutz to get word to her through local Legitimists that he was on the scene and needed to see her, and on November 6, only a week before her departure date, he led the police and military forces to her hideaway. After Deutz had left and just before the authorities were ready to pounce, the duchess looked out the window and sensed what was happening. She and three close companions immediately ran up the stairs and into a secret hiding place off the duchess’s attic bedroom: a small closet behind the fireplace. With the duchess inside this tiny compartment for the next sixteen hours would be her stalwart Charles, comte de Mesnard; her lady-in-waiting Stylite de Kersabiec; and Achille Guibourg, a dashing attorney with whom Samuels convincingly suggests the duchess was having a steamy affair. The soldiers scoured the home but found no one. Only after they lit a fire in the fireplace to keep warm did they accidentally smoke out the duchess and her companions. “I am the duchesse de Berry,” she grandly announced as she emerged from the hiding place. “You are French soldiers. I entrust myself to your honor.”

The search was over, but the travails of the duchess were not. She was pregnant, in all likelihood with Guibourg’s child. The government kept her in prison until she gave birth in the hope of destroying her support, yet her reputation with her followers remained untarnished. “She had,” Samuels writes, “fought a war against liberalism, a war against modernity. And in the eyes of the Far Right, this made her much more than the commander of an army or the leader of a party. It made her a saint.”

Deutz was demonized in the process. Despite his conversion, the conservative press repeatedly described him as a “Jew by birth,” “the Jew Deutz,” or “even the ‘odious Jew.’” The payoff he received inevitably called to mind the story of Judas and his betrayal of Jesus for thirty pieces of silver, reinforcing Christian stereotypes of Jewish treachery and greed. “We have a second Judas,” exclaimed the Legitimist newspaper La Quotidienne soon after the duchess was taken into custody. The famous French Romantic writer François-René Chateaubriand, an important supporter of the duchess, described Deutz as “the descendant of the Great Traitor . . . the Iscariot in whom the Satan had entered.”

The Judas story became an allegory for the widespread conservative perception that the French Revolution had made a disastrous error in granting Jews equal citizenship. Just as the duchess had trustingly brought Deutz, a commoner and a convert, into her orbit only to see him undermine her rebellion, generous France had brought Jews into the fabric of the nation and bestowed citizenship on them, only to see the Jews respond with treachery. Perceived as quintessentially French—in her indomitable courage, heroism, and patriotic spirit—despite her Italian origins, the duchess was seen as the polar opposite of Deutz, the ultimate foreigner. She herself was alleged to have said about Deutz after her capture: “at least the wretch is not a Frenchman.” This statement was quoted and echoed by numerous supporters, including Victor Hugo, who wrote a poem in 1835 entitled “To the Man Who Betrayed a Woman to Her Foes.”

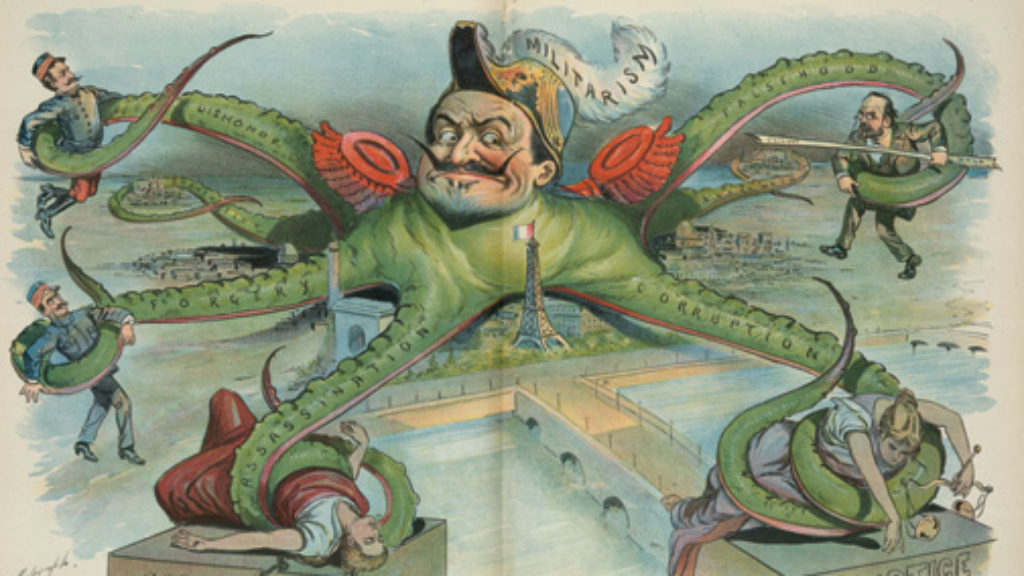

According to Samuels, the vilification of Deutz as a Jew despite his conversion to Christianity signaled a new form of Jew hatred. Unlike the older religious framework of anti-Judaism, which allowed Jews to save themselves by converting to Christianity, the new way of thinking marked Deutz as essentially and immutably Jewish. Descriptions of Deutz and the few illustrations of him that appeared in the press tended to highlight stereotypically “semitic” or even African features. In effect, this was racial antisemitism six decades before the Dreyfus affair.

Deutz’s betrayal of the duchess strengthened the belief that Jews represented all the aspects of liberal modernity despised by antisemites. Samuels’s book powerfully shows that the old-world conservatism of French royalists harbored much greater tendencies toward the new antisemitism than has generally been realized by historians.

After the duchess’s capture, Simon Deutz faced almost universal opprobrium in the French Jewish community (though his father refused to renounce him). By the end of the 1830s, he had blown through the entire half-million franc reward, and, within a couple of years, he had left Paris for New Orleans, where he probably died. The duchess, meanwhile, lost her royal title and was not permitted to raise her children, Henri and Louise.

After lying dormant for decades, the memory of Deutz and his act of betrayal resurfaced in the 1880s and particularly in the decades between 1890 and 1910. For his part, Édouard Drumont was frank about his reasons for dredging up the story of Deutz’s portrayal of the duchess: “Let me just say . . . how charming I find this episode to be! How all the actors fit their roles!” He explains: “Here is the descendant of the Bourbons, the knightly, intrepid Aryan, convinced that the whole world is like her, breathing through her finely wrought nostrils the odor of gunpowder. . . . Whom will she choose to trust? Will it be some artisan’s son from the South of France . . . ? No . . . it’s the oily, viscous, creeping, thick-lipped Jew who seizes hold of that confidence.”

The reader of this arresting historical narrative is left with an uneasy paradox: Drumont was, in a way, right. The two protagonists really do fit their stereotypical roles a bit too well. It is part of Maurice Samuels’s achievement that the duchess becomes a sympathetic character, but try as he might, he cannot do the same for Simon Deutz. Nonetheless, Samuels has told a tale that vividly illustrates the contrasting meanings of the French Revolution in early nineteenth-century French political culture—and shows how Jews, or at least the perfidious Jews of counterrevolutionary imagination, were central to the story.

Suggested Reading

Drawing Conclusions: Joann Sfar and the Jews of France

The great French comic artist is now working at the height of his considerable powers, and he is obsessed with questions of Jewish identity and life in Europe.

33 Days and Four Years

Leon Werth chronicled both the chaotic flight of French civilians from the advancing Germans and the long years of a French Jew living in "free" France.

An Affair as We Don’t Know It

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit.

Richard Wolin on Arendt’s “Banality of Evil” Thesis

Seyla Benhabib responds to Richard Wolin's critique of her review of Bettina Stangneth's Eichmann Before Jerusalem.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In