33 Days and Four Years

On the dedication page of The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry apologized to his young readers:

I ask children to forgive me for dedicating this book to a grown-up. I have a serious excuse: this grown-up is the best friend I have in the world. I have another excuse: this grown-up can understand everything, even books for children. I have a third excuse: he lives in France where he is hungry and cold. He needs to be comforted.

His friend was the Jewish writer Léon Werth, who was indeed hungry and cold in France in 1943. After the Nazi invasion, Werth had gone into hiding in the Jura countryside. Saint-Exupéry wrote the dedication in New York, where he was preparing to leave for North Africa as a pilot for the Free French Air Force. The Little Prince was published later that year, but Werth was not to see a copy until after the war, by which time Saint-Exupéry was dead, having disappeared while flying a reconnaissance mission from Corsica in 1944.

The friendship between Saint-Exupéry, the scion of a conservative aristocratic French family, and Werth, a leftist novelist-critic and the son of a Jewish clothing merchant, who spoke out forcefully against French colonialism, fascism, and Stalinism, was an unlikely one. They met in 1931 and, despite a 22-year age difference, forged a friendship remarkable in its intimacy and sympathetic exchange of views. Saint-Exupéry had arrived in New York in 1940 armed with a precious manuscript, Werth’s 33 Days, planning to use it to win American sympathy for France in its hour of defeat.

The text was Werth’s first-hand chronicle of the chaotic exodus of French civilians who, on order from the government, fled from the north of the country, joining refugees from across the Belgian border in advance of the German army. It had taken him 33 days to travel to Saint-Amour, a village near the Swiss border, ordinarily an eight-hour trip from Paris. German planes strafed and bombed the roads, which were clogged with everything from tanks to pushcarts, from horse-drawn wagons to automobiles without gas. An estimated eight million people were on the road, and Werth’s day-by-day account puts a human face on these numbers.

Saint-Exupéry wrote an introduction to the smuggled text and negotiated a contract with the Brentano’s publishing company to publish it in English. But the book never appeared and the manuscript disappeared. It was rediscovered in 1992 and published in France to great acclaim, but a copy of Saint-Exupéry’s introduction did not come to light until 2014. This elegant English-language edition, ably translated by Austin Johnston, is the first to include the introduction of Werth’s best friend.

Although the publication of 33 Days was long delayed, Werth’s Deposition 1940–1944 appeared in France immediately after the war, in 1946. In this diary, Werth recorded the fixed or fluctuating sentiments of peasants, farmers, shopkeepers, and landowners in his isolated free-zone French village. Wryly, perceptively, despairingly, he deciphered the truth behind the German and Vichy propaganda that was on offer in the village and the neighboring market towns, and he sifted through rumors, anecdotes, and village stories about local incidents.

In the last year of the war, Werth made his way to Paris, hiding in the apartment that his wife Suzanne had established as a safe house for English and Canadian parachutists, Resistance leaders, and Jews in hiding. Not Jewish herself, Suzanne Werth worked with the Resistance network, passing 13 times between Saint-Amour in the free zone and occupied Paris at great risk to herself, her son, and her husband. Together the family witnessed the Paris street battles that accompanied the arrival of Allied tanks in August 1944.

David Ball’s new translation is a generous selection from Werth’s original journal, but Ball’s chosen extracts are concerned primarily with the data of history: events, documents, actions, dialogues. He has pared away many, if not most, of the reflective entries that reveal “l’homme interieur” that Werth’s isolation brought to the fore. The most recent French editions of the journal give us more of Werth’s loneliness, doubts, and self-questioning, and his conflicted feelings about France and the future of Europe.

“There is no trace of Judeocentrism in this diary,” observed Jean-Pierre Azéma in his 1992 introduction, which has been translated (and condensed) for this volume. But, of course, it is more complicated than that. Werth had been largely indifferent to his Jewish heritage for most of his life, but his existential situation was permeated with the fact of his Jewishness: He was in virtual solitary confinement in a remote village, forbidden to publish and earn his livelihood, cut off from his friends and his intellectual milieu, a hostage to anti-Semitism. Though southeastern France did not have a heavy German troop presence, Werth’s safety depended on whether or not his local neighbors denounced him. In his first weeks of hiding, he described himself as a “captive in our summer house . . . I take refuge in my room, like zoo animals in their little den.” It was as a Jew, penned in by Vichy’s anti-Semitic decrees, that Léon Werth discovered his identity as a Jew.

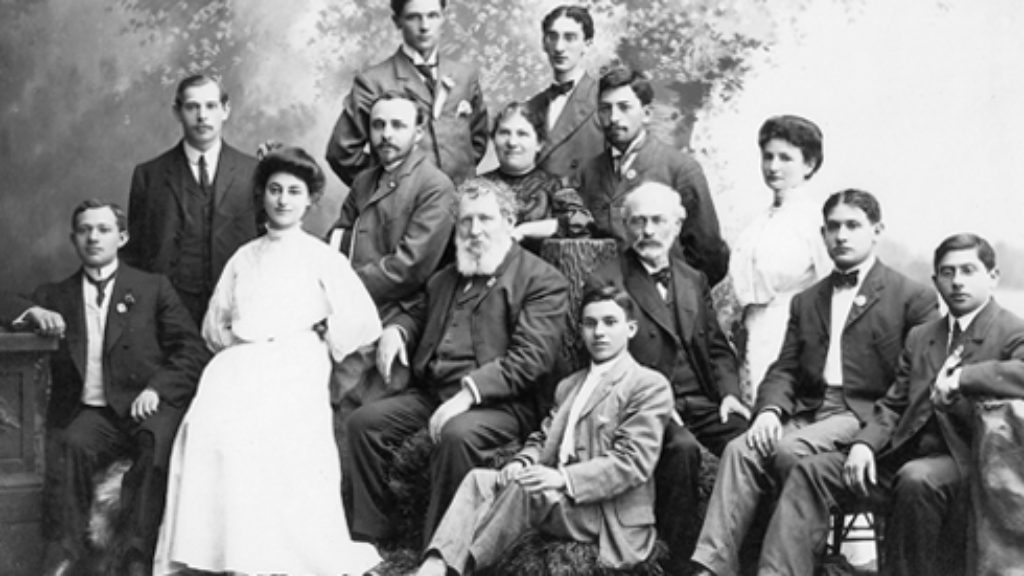

Like many assimilated French Jews, Werth had defined himself as a Frenchman. He embraced the liberal, secular culture of the French Republic that provided and protected his civil rights. His Jewish education was minimal at best. After Werth’s father died when Léon was seven, his intellectual development was taken in hand by his mother’s brother, the young Sorbonne philosopher Frédéric Rauh, who was known as “Rauh the moralist” by his university students. Rauh was a positivist and pragmatist whose books dealt with the question of morality without religious sanctions.

Werth’s first journal entry about Jews is a response to the issuing of the Statut des Juifs, on October 3, 1940, the day of its promulgation:

Vichy is preparing a statute regulating Jews. A Polish Jew at least felt Jewish. People in the Nalewki neighborhood of Warsaw did not conceive of themselves as Polish. But French Jews no longer felt Jewish. Those who felt most Jewish in their hearts were only Jewish through the memory of a few family traditions.

Here, we see Werth holding Jews at arm’s length. Five days later, he describes two kinds of Jews he seems to know, the contemptible materialistic assimilated Jew and the pious observant Jew. He has only contempt for the former: “They’ve lost—and they’re proud of it—all contact with Judaism, not to say with anything resembling religion. They didn’t feel Jewish, they felt rich.” But in the same entry he describes the pious Jews of a past generation, possibly a remembrance of his grandparents:

In Alsace in the middle of the nineteenth century, there was a certain Jewish purity, as there was a Protestant purity. These austere religions offered only demanding things to lean on. Those who practiced them were a suspect group, in the opposition. That led to pride more than to facility.

These distanced observations seem to have been a kind of preparation for acknowledging himself as a Jew. But even as France disowned him, he clung desperately to his French identity. He wrote on October 21, “I care about a civilization, about France. I have no other way of dressing. I can’t go out completely naked.” He is not quite ready to don his Jewish identity.

It is not until the entry of December 9, 1940, that we find Werth clearly identifying himself as a Jew, though he worried about a narrowing of his world view: “I’m a Jew, but am I going to reduce the world to the comforts Jews will have in the Europe of tomorrow?” Seven months later, on July 9, 1941, he wrote, “I am going to Lons to declare that according to the terms of the law of June 2, 1941, I am Jewish.”

I feel humiliated. It’s the first time that society has humiliated me. I feel humiliated, not because I’m Jewish, but because I am presumed to be of inferior quality because I’m Jewish. It’s absurd; it may be the fault of my pride, but that’s the way it is.

[I’m being forced] to claim that I’m from a Jewish nation to which I felt no connection. . . . But if a foreigner means to humiliate me through this nation, I am hurt, and I don’t know if it’s this nation or myself I must defend. But simple dignity obliges me to identify myself with it. . . . It would be just too cowardly to deliberate whether or not I feel Jewish! If you insult the name of Jew in me, then I am Jewish, totally Jewish, Jewish to the tips of my toes, Jewish to my very guts. After that, we’ll see.

Werth went to the market town to register as a Jew, as farmers milled about with their animals to register their weights:

As others go to declare their cattle and the weight of their pigs, I went to the prefecture to declare I was Jewish. . . . I made my declaration at the prefecture. I threw out the word “Jew,” as if I was about to sing the Marseillaise.

From this point on he begins to record meticulously everything he learns about the deportations and massacres of the Jews.

On March 27, 1944, he wrote, “Now and then I wish—oh, I’m well aware it’s a very faint wish—that I were deported to the depths of Poland, to be with the people who are suffering, with those suffering the most.” But he self-consciously adds (though Ball does not translate this): “Heritage of Christianity. Christianity by osmosis.” Werth knew that the idea of suffering as redemptive was not a Jewish one, even though he knew little else about the religion for which he suffered.

In his late journal entries of 1944, Werth wondered skeptically about what kind of Europe would be possible after the war. “Is there a Europe?” he asks. “Founded on what? on Christianity? on reason? on experimental science? Europe seems very far away to me.” Hearing General De Gaulle’s radio broadcasts from London, Werth wanted to believe that there was another France, a “spiritual nation,” that could be restored after the war. But he also feared that under fascist brutality it had lost the ability to conceive of itself as an idea, an ideal of liberty and justice.

When the Allies marched into Paris, Werth experienced the giddy excitement of victory, of deliverance. But at this moment of triumph, he also saw Frenchwomen accused of having German lovers being marched with shaved heads through the Paris streets. Even the public abasement of captured German soldiers unsettled him:

But the humiliation of those men makes me suffer. It is necessary, it is even justice itself. I approve of it, it satisfies me, it soothes me, and I cannot rejoice at it. . . . I’m forgetting nothing [i.e., the massacres, deportations, and tortures]. But when a human being is humiliated, his humiliation is in me.

The full humiliation of the Jews was in Werth during the war years. But it was as a proud Frenchman that he joined the crowd that welcomed De Gaulle.

Suggested Reading

Schechter’s Seminary

Solomon Schechter is remembered as the founder of Conservative Judaism—but who are his religious heirs?

Poems Like Mountains

“I was a year old,” Rivka Miriam says, “and my father would hold me in his arms and throw me up and down and I laughed and laughed and laughed. Each time he threw me up he’d yell in Yiddish ‘Rivkela Rivkela where’s Savta?’ ‘Killed.’ ‘Rivkela Rivkela where’s Miriam?’ ‘Killed.’ ‘Rivkela Rivkela where’s Chaim?’ ‘Killed.’ He’d say all the names…

Original Sins

John Judis book about Truman's Middle East policy isn't a rant, but it's not exactly history either.

The Apocryphal Psalms of David 1:15–20

In 1902 Abraham Harkavy published two previously unknown psalms and parts of two others from a manuscript in the Cairo Geniza. They may date back to the Second Temple.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In