Radically Enlightened Jews

In the career of an average scholar, a book on the scale of Revolutionary Jews from Spinoza to Marx would constitute a landmark, if not a magnum opus. But if you were to line up all of Jonathan I. Israel’s books on a shelf, it might easily escape your notice. It would be dwarfed by his three-volume, nearly three-thousand-page history of the Enlightenment. And even if you were to take those big books away, another half a dozen hefty tomes would remain on a variety of subjects that might lead you to overlook his newest one. These other books include a couple of early works on Jewish history, most notably his European Jewry in the Age of Mercantilism, 1550–1750, which has been since its publication in 1985 a key text of early modern Jewish history.

Revolutionary Jews isn’t really a return to Jewish history on Israel’s part as much as it is a kind of postscript to his vast study of the Enlightenment, in which only one Jew plays a major role, albeit the starring one. According to Israel, Baruch Spinoza founded what he calls the “Radical Enlightenment” in the middle of the seventeenth century. In a brief (for him) book published twelve years ago, Israel described this “Radical (one-substance) Enlightenment” as an intellectual movement that conflated “body and mind into one, reducing God and nature to the same thing, excluding all miracles and spirits separate from bodies, and invoking reason as the sole guide in human life, jettisoning tradition.” Israel distinguishes this from the inferior “moderate (two-substance) Enlightenment . . . postulating a balance between reason and tradition, and broadly supporting the status quo.”

Elsewhere,Israel has endeavored to show at great, indeed phenomenal, length how Spinoza’s one-substance doctrine became the foundation for the Radical Enlightenment’s principles, on the basis of which society could be made “more resistant to being manipulated by religious authority, autocracy, powerful oligarchies and dictatorship, and more democratic, libertarian and egalitarian.” After tracking the development of these radical ideas all over Europe, and in the Americas as well, for more than a century after Spinoza’s death, Israel seeks to show how the French Revolution was essentially an attempt to put its principles, rather than those of the moderate Enlightenment, into practice.

Revolutionary Jews makes no grand argument about the impact of the Radical Enlightenment on the trajectory of Jewish history. After reiterating much of his earlier analysis of Spinoza and amplifying it in certain respects, Israel seeks in this book mostly to show how a few extraordinary Jews absorbed or rejected the ideas of Spinoza andthe Radical Enlightenment in the years before 1850. His discussions of figures ranging from Spinoza’s contemporary Isaac Orobio de Castro to Karl Marx are characteristically rich and surprising but also sometimes problematic.

One of Israel’s most provocative discussions is his account of Moses Mendelssohn, who is generally contrasted to Spinoza as a champion of the moderate Enlightenment—and for good reasons. Spinoza’s God is immanent in nature if not equivalent to it (hence his famous phrase “Deus sive Natura,” God or Nature); Mendelssohn’s is transcendent. Spinoza rejects the very possibility of revelation; Mendelssohn reaffirms its enduring truth. Spinoza proclaims Jewish law to be obsolete; Mendelssohn upholds its authority. In the eyes of most scholars, the contrast is, in short, one between a seventeenth-century renegade from Judaism and an eighteenth-century thinker who famously sought to defend and perpetuate the religion for a new age.

However, Israel suspects that the differences between the two philosophers are merely superficial and that Mendelssohn was at bottom much more in tune with Spinoza than he wanted to appear. He goes so far as to suggest that Mendelssohn may have been a covert adherent of Spinoza’s one-substance doctrine, whose public defenses of Jewish doctrines were insincere gestures designed to maintain his credibility within his community. But whatever Mendelssohn truly believed about God and nature, his practical program was essentiallyaligned with the Radical Enlightenment.

In his classic work Jerusalem, Mendelssohnmay have defended the divine origin of Jewish law, but he simultaneously sought, according to Israel, to render it inefficacious when heargued for the separation of church and state. Israel writes:

Mendelssohn seconded Spinoza’s assault on institutionalized religious authority (albeit refraining from pointing this out) by urging the need for total separation of religious life and the churches, as well as individual conscience and philosophy, from the functions and duties of

the state.

Despite its “general repudiation of Spinoza’s substance monism and Bible criticism,” Jerusalem “was undeniably a sanitized reworking of the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus aimed at bolstering toleration and personal liberty, and promoting equal rights for all, while insisting the Hebrew Bible supported such a libertarian stance.”

This is an unconventional view of Mendelssohn, but, as it happens, it is close to one that I have maintained for more than thirty years without persuading many fellow scholars that I am correct. It came as a pleasant surprise, therefore, to encounter a historian of Israel’s stature partly relying on my interpretation. However, I’ll be surprised again if Israel makes a dent in the long-standing consensus that Mendelssohn’s reconciliation of Judaism with the philosophy of the Enlightenment ought to be taken at face value.

Roughly contemporary with Mendelssohn, but a bit younger, the Sephardi native and resident of the large Jewish community in Surinam, David Nassy, was a less circumspect figure, who is more to Jonathan Israel’s liking. A startlingly well-educated provincial living in freer circumstances than just about any Jew in Europe, Nassy was immersed in “all aspects of the trans-Atlantic Enlightenment” by the time he was thirty, in 1777. As his ideas consolidated, his critique of Jewish society grew broader:“rigid observance, tradition and law, and indifference to the world beyond Judaism, became for Nassy an insufferable barrier to individual development, a focus of ever-sharper enlightened critique.”

Living in a “relatively tolerant society deep in the tropics, Nassy had little need to be overly reticent about his revolutionary creed.” He and a few others like him, who belonged to “the Jewish New World Enlightenment clique,” were attracted to the Radical Enlightenment as “the only uncompromising emancipatory universalism available.” They eventually adopted “a comprehensive . . . political ideology proclaiming equality, democracy, full freedom of expression and ending religious authority’s hold over social organization.”

For people with such lofty egalitarian ideals, the creation of the United States in their own lifetimes and general vicinity definitely represented an encouraging advance. But only a qualified one, given the inequities it preserved—above all, the institution of slavery. Israel himself pauses to note how the American Revolution, which he sees as having been too largely a product of the Moderate Enlightenment, “initially made strikingly little difference to the continuing exclusion of Jews from office, political participation and equal civil rights.” He claims that “apart from New York State . . . all other states retained strict ‘religious tests’ for officeholders requiring avowed allegiance to Christ, thereby wholly debarring Jews from office until well into the nineteenth century.”

To illustrate this, Israel adduces the case of Pennsylvania, where a Jewish plea for full civil rights was rejected in 1783. He fails to mention that a similar petition met with success a few years later, and that by 1790, the Jews of Pennsylvania had what they wanted. Even more significantly, he overlooks the case of Virginia, where the passage in 1786 of the justly celebrated Act Establishing Religious Freedom, written by Thomas Jefferson, endowed everyone, including Jews, with full civil rights. Moreover, by the end of the eighteenth century, the constitutions of South Carolina, Delaware, Georgia, and Vermont likewise permitted Jews to hold office.

These are somewhat inconvenient facts for an author who believes:

Jews, Sephardic and Ashkenazic, everywhere in the Americas just as in the Old World, needed a comprehensive revolutionary rationale and agenda measuring up better than did the American Revolution to the new principle of “universal and equal rights.”

Israel could argue that in the case of Virginia, at least, it was really “the Jeffersonian (radical democratic republican) tendency in the American Revolution” that made the difference—but that’s not the whole story. The “moderate” Enlightenment seems to have had an emancipatory momentum of its own.

The second half of Revolutionary Jews moves beyond the Enlightenment era to examine a gallery of radical Jewish thinkers and writers from the period of the French Revolution through to the Revolution of 1848. Some of them broke with Judaism and the Jewish people altogether; others blended their radical ideas with their Jewish loyalties. Israel has a certain amount of admiration for all of them but seems to prefer those who remained within the fold, if in admittedly untraditional ways.

Israel doesn’t point to any direct link between Spinoza and the Polish-born librarian Zalkind Hourwitz, but he does characterize him as “the Ashkenazic personage who most fully articulated the new trans-Atlantic secular Jewish revolutionary identity in France” and made the radical case for Jewish emancipation on the very brink of the French Revolution. He also made the case for black emancipation, “asserting the unity of mankind and universality of equal rights.”

When his narrative returns to Germany, Israel returns to Spinoza’s direct legacy.The great poet Heinrich Heine, he writes, “learnt early to associate Spinoza with battling ignorance, obscurantism, prejudice, injustice and oppression, and the prevailing reality surging all around him.” Together with Ludwig Börne, Heine became a model “for a whole generation of aspiring young revolutionary Jews.” He was distant enough from any kind of Jewish faith to famously undergo an opportunistic conversion to Lutheranism (his self-proclaimed “ticket of admission” to European culture) but never really became any kind of a Christian and even retained a measure of Jewish cultural identity.

In exile in France in the 1830s, Heine wrote his three-volume essay On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany, in which he foreshadowed Israel’s own work, hailing Spinoza as a champion of humanity. Heine also was early in discovering “hidden underground philosophical networks” throughout Europe, which, Israel writes, represented “a working out of Spinoza’s ideas deep in the underground of European culture.”

Moses Hess, the renegade product of a traditional Jewish home, “imbibed the heretical ‘Spinoza ideology’” from Heine’s writings and went on to write A Holy History of Mankind, which bore the subtitle: From a Young Disciple of Spinoza. In the 1830s, he “ardently reworked Heine’s notion of Spinozism as a world-redeeming force.” Hess’s alignment with the Radical Enlightenment was qualified even at the beginning of his career by “messianic longings and dreaming” of a new world, which he attempted to achieve through revolutionary activism. Later, after the failure of the Revolution of 1848, these yearnings came to focus on the idea of Jewish resettlement inthe Land of Israel. Even as a proto-Zionist, however, Hess remained a self-declared Spinozist, who applauded the fact that his master “conceived Judaism to be grounded in Nationalism, and held that the restoration of the Jewish kingdom depends entirely upon the will and courage of the Jewish people.”

Heine’s third cousin and erstwhile ally Karl Marx studied Spinoza’s writings intensively in the early 1840s. Israel writes:

During this formative early period, it was arguably also Spinoza who most decisively shaped Marx’s general view of man as being, in body and mind, purely a product of nature and then political outlook, his separation of all theology and religion from politics and society, his self-awareness as an active, committed democratic republican revolutionary.

But this did not last. Marx broke with the tenets of the Radical Enlightenment in 1843, when he plunged, as Israel puts it, into “an inexorable materialist dialectic” in which “the focus on individual autonomy, freedom of expression and democracy had evaporated.”

It’s a bit strange to encounter a discussion of modern Jewish revolutionaries in which Karl Marx represents a fall from grace, and it’s hard not to relish this particular twist in Israel’s story. Israel’s denigration of Marxism is not a rejection of the left but reflects a conviction that Marx pointed it in the wrong direction. The Radical Enlightenment that he outgrew, in Israel’s eyes, is a tradition that ought to remain vital.

Israel believes that we can keep this tradition vital not simply as human beings but specifically as Jews, if not as practitioners of Judaism. While he acknowledges that there is no absolute contradiction between adherence to some sort ofreligion and acceptance of the teachings of the Radical Enlightenment, the path that Israel himself prefers is an entirely secular one. The Jews, he argues, can rally around Spinoza’s ideas, which do have some roots in their tradition and their experience of oppression and liberation, as Spinoza himself made clear. They can belong to the enlightened sect whose role, for Spinoza, was to provide “the key to what he envisages as a better human future, advancing a secular ethics edging surreptitiously forward, staunchly opposing oppression and the delusions of the majority.” These goals can perhaps still serve as the basis “of a Jewish secularist democratic (and secularized Marrano) identity.”

This may not be that much of a stretch. Decades ago, Leo Strauss acutely observed that modern Judaism was “a synthesis between rabbinical Judaism and Spinoza.” Today, on the whole, there is less of the classical rabbis and more of Spinoza in the mix. One can readily imagine the emergence of a Judaism that would contain an even greater dose of one-substance radicalism. But if that were to develop, I think, it would be less likely to provide wavering Jews with a compelling reason to remain united than to induce them to conclude, sooner or later, that they could best pursue their enlightened goals simply as human beings, without any of the old baggage.

Suggested Reading

A Very Jewish Encounter

The text is full of underlining, circled words or phrases, arrows, careful cross references, and copious comments in Yiddish, English, Spanish, and Hebrew. It’s what my students at Ohio State might call an “extreme reading.”

Lands of the Free

It is sad to watch the territorialists engage in their wild goose chases all over the globe at a time when multitudes of Jews were in need of a place, any place, to go.

The Martyr of Reason

On Saturday evening, December 31, 1785, the eminent Enlightenment philosopher Moses Mendelssohn left his house to deliver a manuscript. He had finished it on Friday afternoon but, as an observant Jew, Mendelssohn waited until the Sabbath concluded to bring it to his publisher. He died a few days later on January 4, 1786, at the age of 56.

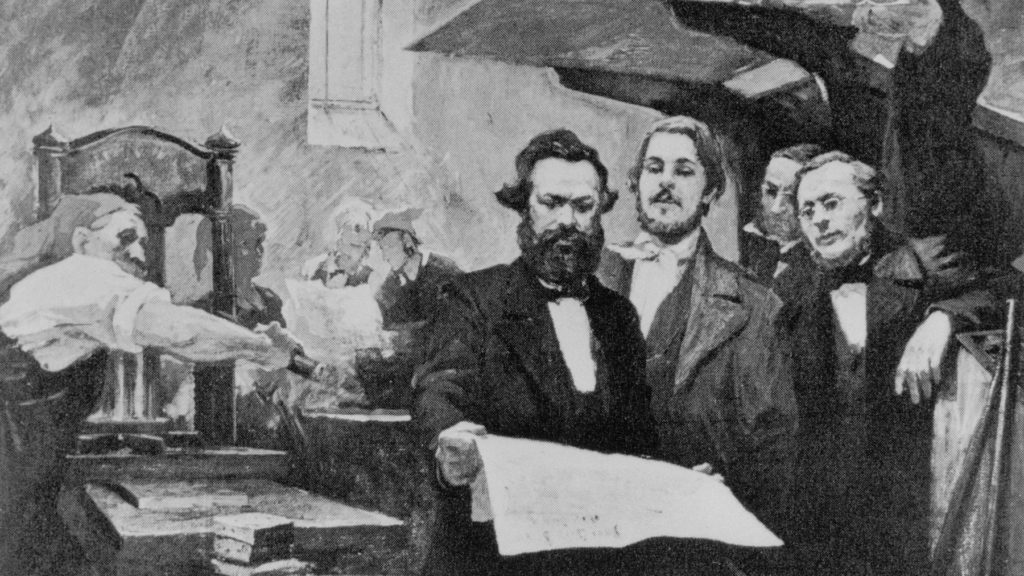

Karl Marx, Bourgeois Revolutionary

Jonathan Sperber's new biography paints Karl Marx as a surprisingly conventional 19th-century paterfamilias.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In