Like a Son of Man

“Any discussion of the problems relating to Messianism is a delicate matter,” wrote Gershom Scholem, “for it is here that the essential conflict between Judaism and Christianity has developed and continues to exist.” This “essential conflict” is not merely the identification of a particular man as a messiah but about the nature of the messianic figure.

What should we expect a messiah to do, and what kind of being should he be? In Jewish tradition, the primary expectation of the messiah is that he restore the kingdom of Israel by defeating the enemies of his people. He must be an exceptional individual, but nonetheless human. The role of Jesus of Nazareth, the Christian messiah, is to save people from sin so that they can enjoy eternal life. He is not only Son of God, a title that can be understood in various ways, but actually divine. (Eventually, although not in the New Testament, Christianity would proclaim him “one in substance with the Father.”) Of course, his earthly career did not end in victory but in a shameful death, the ultimate sacrifice to atone for sin. This humiliation was overcome by his resurrection from the dead, and Christians await his second coming in victory at the end of history.

According to Christian tradition, all of this was predicted in the Old Testament, although the predictions admittedly went unrecognized before Jesus’s death and indeed are still not recognized by Jews. Modern scholarship, both Christian and Jewish, generally rejects that claim and sees the traditional Christian reading of messianic prophecy in the Hebrew Bible as a retrojection of Christian beliefs. About a decade ago, the eminent (Jewish) talmudic scholar Daniel Boyarin generated headlines by claiming that the Christian understanding of the divinity of the messiah was actually grounded in an ancient Jewish tradition that had never died out. The claim was met with skepticism, notably by another eminent talmudist, Peter Schäfer, who happens to be Christian (as am I). Now another distinguished Jewish scholar, Israel Knohl, has taken up the issue.

Knohl, who teaches at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has been discussing this subject for many years, and his new book, The Messiah Confrontation, is the most complete and accessible treatment of his provocative views. Knohl’s interpretation is a cousin to Boyarin’s, insofar as both argue for the Jewish roots of positions that are commonly regarded as distinctively Christian. But the details are very different. Boyarin based his argument largely on the figure of the Son of Man in the book of Daniel and the Pseudepigrapha, while Knohl relies on the Dead Sea Scrolls. He argues that the basic conflict over the nature of the messiah was originally an intra-Jewish one between the Pharisees and the Sadducees, which predated Jesus. The Sadducees, who initially condemned Jesus to death, were a small antimessianic group that disappeared from history a generation later. For other Jews, notably the Pharisees, arguing about who was or was not the messiah was nothing out of the ordinary. They did not condemn other messianic pretenders to death, and they would not have condemned Jesus. Knohl writes:

Unfortunately, Jesus’s judges were not Pharisees, the predecessors of the rabbinic sages. Jesus’s judges were Sadducees, engaged in a bitter controversy with the Pharisees on this very question of the Messiah. In other words, the trial of Jesus was not a confrontation of Jewish and Christian doctrines, but a conflict between two internal Jewish positions in which Jesus and the Pharisees were on the same side.

Knohl’s story begins many centuries before the time of Jesus—in fact, before the Babylonian Exile. He sketches two fundamentally different religious ideologies in ancient Israel and Judah. On one hand, the Torah had only a marginal place for a king, and it insisted on a clean separation between the human and divine realms. On the other hand, the prophet Isaiah and certain psalms (2, 45, 110) portrayed the king/messiah as a demigod who could be called the Son of God. (The term “messiah,” mashiach,simply means anointed one, since kings, as well as priests and possibly also some prophets, were anointed with olive oil to signal that they were chosen by God). This royal ideology, with its exalted view of kingship, ultimately derived from the mythology of the ancient Near East and was at home in Jerusalem. The ideology of the Torah, which was critical of kingship, was influenced in some part by traditions from northern Israel, represented by the prophet Hosea.

Knohl’s interpretation of some of the relevant texts, such as Isaiah 7:14 and 9:6, is questionable. Isaiah 7:14 famously reads “Look, the young woman”—in Christian renditions: “a virgin”—“is with child and about to give birth to a son. Let her name him Immanuel.” And Isaiah 9:5 announces “For a child has been born to us, A son has been given us. And authority has settled on his shoulders.” It seems unlikely that the prophet was speaking of a figure who would arrive in the distant future rather than in his own time. But the general picture Knohl paints of two essentially opposed biblical approaches to kingship is certainly right. He is also right that the messianic tradition went into abeyance for centuries after the aborted restoration under Zerubbabel, the promising governor who led the first wave of Judeans returning to Judea from the Babylonian captivity. It was only revived in the Hasmonean era, when the descendants of the Maccabees made themselves kings, even though they were not descendants of David.

The evidence for the return of messianism is found in the Dead Sea Scrolls and in the so-called Psalms of Solomon, which were composed in Hebrew in the middle of the first century BCE but only survived in Greek translation. Knohl, like many scholars, regards these psalms as Pharisaic. He writes of the author of the Psalms of Solomon that he “was assuring his audience that a Messiah—in fact, a semidivine Messiah—of the house of David would soon arrive to put things right.” But the Psalms of Solomon do not really highlight the semidivine status of the king, although they clearly draw on Psalm 2, in which God tells the king/messiah that he is his son. Knohl is strangely silent about more convincing proof texts for his argument, such as the Dead Sea Scroll text 4Q246, which speaks of a figure who will be called “Son of God” and “Son of the Most High” in terms that correspond directly to what is said of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (1:32, 35). He also fails to mention that in the late first century CE apocalypse of 4 Ezra, God refers to “my son, the messiah.” These texts provide much stronger support for Knohl’s claim that the messiah was widely viewed as the Son of God in the time of Jesus than do the Psalms of Solomon.

The main qualification for the royal messiah in the Hellenistic and early Roman periods, however, was that he be a warrior who would overthrow illegitimate kings and drive out foreign powers, first the Greco-Syrians and then the Romans. The Psalms of Solomon pray that God “gird him with strength to shatter in pieces unrighteous rulers, to purify Jerusalem from nations that trample her down in destruction.” There are similar prayers in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The upshot is that, as a nonwarrior, Jesus of Nazareth was poorly qualified for the messianic role. The puzzling historical question is not why he was not accepted as messiah by the majority of Jews but why anyone ever thought he was the messiah at all.

The answer lies in the fact that there were other ways of thinking about a messiah current in this period. The best known of these was the idea of a priestly messiah, known as the Messiah of Aaron, who would serve as high priest in the messianic age. This figure would atone for Israel’s sins by offering the prescribed sacrifices and observing the rituals properly. Jesus was not a priest (although the New Testament Epistle to the Hebrews casts him in that role), so the messiah of Aaron does not shed much light on his messianic career. There was, however, another view of atonement that received its classic expression in Isaiah 53:5 in the figure of the suffering servant, who was “wounded because of our sins, crushed because of our iniquities . . . and by his bruises we are healed.” The identity of this figure in Isaiah is much disputed. He probably personifies the experience of Israel during the Babylonian Exile. In any case, the figure was not a messiah until he was interpreted as one by the followers of Jesus after his death, as it seemed to anticipate his suffering and crucifixion.

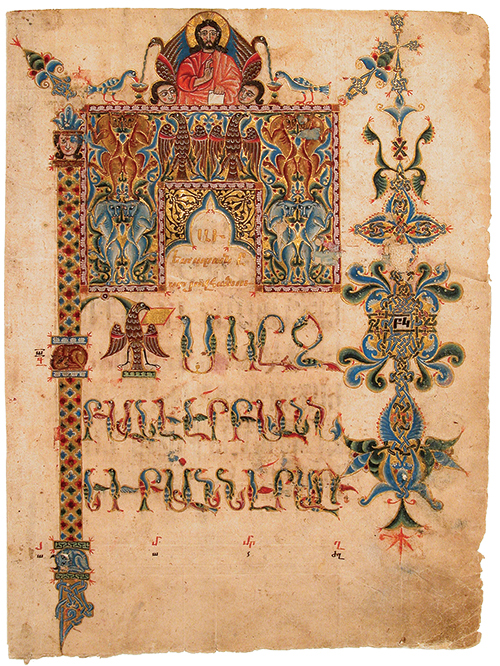

Title page of the Gospel of John by Sargis, 1300–1310. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

According to the Gospel of Mark, Jesus already understood his mission in light of the suffering servant:

He began to teach them that the Son of Man must undergo great suffering and be rejected by the elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again. He said all this quite openly. (Mark 8:31–2)

Nonetheless, it is clear that his disciples were surprised and shocked when he was arrested and crucified. Since the work of William Wrede more than a century ago, most New Testament scholars have held that the predictions of his suffering were put in his lips after his death by the evangelist. Knohl, however, claims that

three Qumran texts present the idea of an unusual messianic figure who is both exalted—elevated to a quasi-divine status—and suffering.

And like Isaiah’s suffering servant, he also atones for all the members of his generation.

Following the late David Flusser, he suggests that Jesus had met people from Qumran or learned of their beliefs from John the Baptist.

None of these Qumran texts, however, withstands scrutiny. One is a variant in a manuscript of the book of Isaiah. Isaiah 52:14 reads mishchat mei’ish mar’eihu (“marred was his appearance, unlike that of man”). The Qumran manuscript adds one letter, a yud, to the first word, which can then be vocalized as mashachti, “I anointed.” The resulting reading “I anointed his appearance unlike that of man” would be very odd, and it is not clear that it should be taken to mean “I made him a messiah.” The simplest explanation of the reading is that it is a scribal error.

Knohl’s second text is a very fragmentary Aramaic text about a priestly figure. He is not called a messiah, but he might be the Messiah of Aaron. He endures affliction and rejection. “Lies and falsehoods will be told about him, and all kinds of accusations will be made about him.” Nonetheless, he atones for his generation. Knohl assumes that he atones by his suffering, but that is a large assumption.

The third text, known as the “self-glorification hymn,” is also extremely fragmentary. The most striking thing about it is that the speaker claims to have a throne in heaven. This brings to mind Psalm 110, in which the king is invited to sit at God’s right hand, but the figure in the Qumran text is not seated on the right hand, and the description does not have other overt messianic connotations. This figure also boasts of enduring evil. Some scholars think he may also be the priestly messiah, others the exalted teacher of righteousness, a key figure in the formation of the sectarian movement described in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Again, there is no suggestion that whatever suffering he endures atones for anyone else. These Qumran texts, then, do not significantly alter our picture of Jewish messianism or lend credence to the idea that Isaiah 53 was understood to predict a suffering messiah before the death of Jesus. Wrede’s explanation remains the most likely one: the messianic interpretation of the suffering servant was invented by the followers of Jesus as a way of explaining his shocking death.

The passage in Mark in which Jesus allegedly spoke openly about his suffering, death, and resurrection does not use the first-person pronoun or speak of the messiah. Instead, it says that “the Son of Man must endure great suffering.” This is an allusion to the book of Daniel, in which Daniel sees “one like a son of man” coming on the clouds of heaven and receiving a kingdom (“son of man,” bar enash, was an idiom for “human being”). Knohl devotes a chapter to Daniel, but I think he misreads the vision badly. He takes the figure on the clouds as a symbol of Israel or the Jewish people. However, the idea that the Son of Man is a symbol for Israel does not appear until the third century CE. All the early interpretations of Daniel’s vision assume that the “one like a son of man” is a heavenly being. Besides the Gospels, the early interpretations include the Similitudes of Enoch, an apocalypse from around the turn of the millennium, and 4 Ezra, from the late first century CE. In both of these texts, the Son of Man figure is identified as the messiah. When Jesus says in the Gospel of Mark that the Son of Man must suffer, or that he will come on the clouds of heaven, no one ever thought that he was referring to the Jewish people.

At least in the first century CE, Daniel’s Son of Man was understood as a heavenly messiah. This idea was of fundamental importance for early Christianity. After Jesus’s death, his followers came to believe that he was risen from the dead, taken up to heaven, and would come again as the Son of Man on the clouds. The Gospels claim that Jesus often spoke of the Son of Man and imply that he was referring to himself. Whether he actually did so is difficult to determine. It is unclear why anyone should expect him to arrive on clouds while he was still alive and much easier to see why this expectation would arise after his death. It is also possible, however, that Jesus spoke of the Son of Man as a heavenly savior without claiming that he himself was that figure.

It is extremely difficult to know how Jesus understood himself and his mission. According to Mark 8:30, he sternly ordered his disciples not to tell anyone that he was the messiah. Many New Testament scholars see this messianic secret as a way of explaining why he had not been openly hailed as the messiah during his lifetime. There is one exception to this—his entry into Jerusalem riding on a donkey to shouts of “Hosanna to the Son of David.”

Of course, we don’t know whether Jesus actually did this, but in the first century CE, there were several sign prophets who tried to reenact scenes from biblical history. One told his followers that the waters of the Jordan would part before him, as the Red Sea had parted before Moses. Another promised that the walls of Jerusalem would fall down as the walls of Jericho had fallen before Joshua. Jesus was evoking a prophecy from the book of Zechariah: “Lo your king comes to you, triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey” (Zech. 9:9). These figures were not militant revolutionaries. All seem to have relied on divine intervention to achieve their goals.

Knohl is surely right that neither the Jewish leaders nor the Roman authorities understood Jesus. Arguably, his followers did not understand him either. However, the Romans wanted to suppress any disturbance that might even hint at the restoration of Jewish independence.

The focus of Knohl’s book is on the confrontation between Jesus and the high priest. The story of this confrontation, as told in Mark 14 and parallels, is of dubious historical value. The disciples of Jesus were not present, except Peter “at a distance,” so what was the source of their information? The story is more likely to be a reconstruction by the authors of the Gospels than a transcript of the proceedings.

According to this story, the high priest asked Jesus directly, “Are you the messiah, the son of the Blessed One?” He answers, “I am, and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the Power and coming with the clouds of heaven.” The charge of blasphemy seems to be based, at least in part, on his implicit self-identification as the Son of Man. Knohl argues persuasively that Jesus’s answer would not have been judged as blasphemy by the Pharisees. Only the Sadducees, who held to the antimessianic ideology of the Torah, would have regarded it as such. But ultimately, Jesus was not crucified because Sadducean judges convicted him of blasphemy. He was executed by the Romans on a political charge, because some people were saying that he would restore the kingdom of Israel.

Whether the Sadducean chief priests had a hand in Jesus’s execution, by handing him over to the Romans, remains controversial. The Gospels consistently claim that they did, and this claim is not implausible, but the issue was not necessarily blasphemy. The Gospel of John (11:47–53) says that some of the chief priests and Pharisees were disturbed by the fact that Jesus was attracting crowds. They worried: “If we let him go on like this . . . the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place and our nation.” At that point, Caiaphas, the high priest, said that it is better to have one man die than to have the whole people destroyed. About fifty years after Jesus’s death, there would again be tension between the Jewish ruling class and revolutionaries. Even if the chief priests did hand Jesus over to the Romans, Knohl is unquestionably right that this was the act of an elite minority.

What, then, are we to make of The Messiah Confrontation? On one hand, Knohl makes an important point (which Boyarin has made in a different way) in showing that the idea that the messiah would be in some sense divine, and could be called “Son of God,” had deep roots in Judaism. Christian theologians would later go beyond this, but the claims made for Jesus in most of the New Testament would not have been considered blasphemous by many Jews at the time.

On the other hand, Knohl’s attempt to find a Jewish pedigree for the notion that Jesus’s death served as an atonement falls short. The idea of redemptive suffering and death were not foreign to Judaism, but no one before the time of Jesus had expected a messiah who would be executed. Knohl’s suggestion that Jesus got his messianic ideas from Qumran through John the Baptist is implausible and unfortunate. It brings to mind a long list of sensational and baseless claims about the Dead Sea Scrolls and the origin of Christianity. From the viewpoint of a Christian scholar, Knohl’s willingness to take the portrayal of Jesus in the Gospels at face value seems a little naive, although it also bespeaks a generous respect for Christian tradition.

The Messiah Confrontation is an engaging, provocative book, and Knohl is certainly on the right track in looking for Jewish roots of Christian beliefs, even if he is not always convincing in locating them.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

(Almost) People

What does it mean to say that books have lives?

What a Friend We Have in Jesus

A new crop of books about Jesus, by Jews and for Jews.

What Jesus Wasn’t: Zealot

When Fox News' Lauren Green asked Reza Aslan why, as a Muslim, he would write a book about Jesus, he answered that it was his job as an historian of religions—which would have been a good answer, if it had been true.

Overturned Tables

Despite his incontestable Jewishness, Jesus never participated in a Seder as the Mishnah describes it any more than he intended for Judeans to abandon biblical law for the worship of God’s only begotten son.

hana blume

First of all, why are all the references - including the author's position - in Christian terminology? Inherent in the description of the Hebrew Bible as The Old Testament is the inference that it is insufficient in itself and is supplanted - as per Christian theology, - by a New Testament.

Also, how is anyone "guilty" of Jesus' death if it is preordained as a part of his destiny? If Jesus lived to a ripe old age and died of a heart attack, what happens to the story? So Jesus must be crucified, and those who enable this are destined to perform the functions that will ensure that outcome.