Dateline Zion

On Friday, September 12, 1941—at the height of the war, just ten days before the Jewish New Year—the rabbis of Jerusalem received an urgent telegram from Kobe, Japan:

350 JEWS APPEAL RESCUE ANSWER IMMEDIATELY WHICH DAY TO FAST YOMMKIPUR.

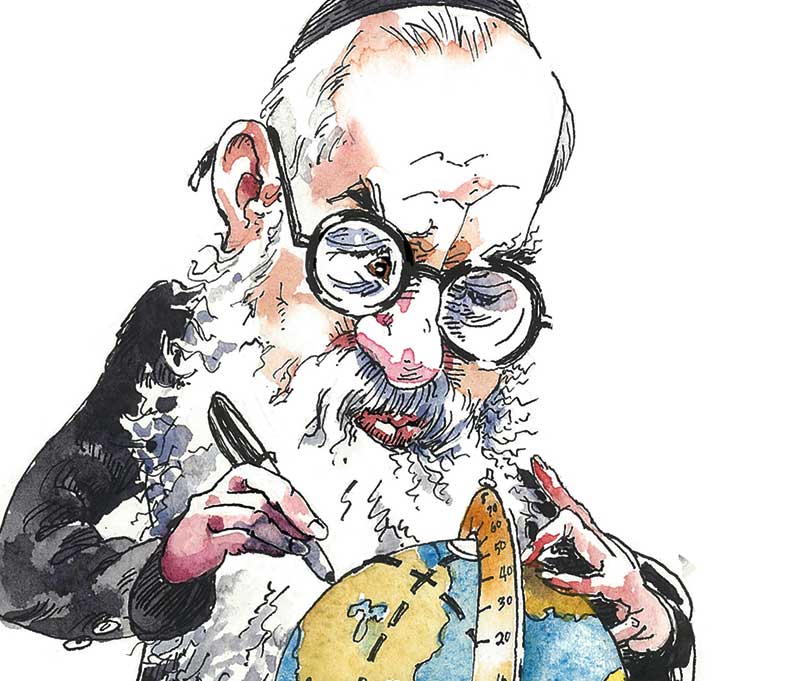

Rabbi Yitzchak ha-Levi Herzog was Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Palestine at the time, having succeeded Rav Kook in 1936. For the last few years, Herzog had worked tirelessly to secure visas, certificates, and funds to help free Jews from all over Europe. In 1940, he had been part of a daring and elaborate plan to enable the students from the famed yeshiva in the Belarusian town of Mir to flee the Nazis via Japan en route to Curaçao. By the late summer of 1941, almost the entire student body of the Mirrer Yeshiva would find itself in Kobe. Now Yom Kippur was fast approaching.

The question of Yom Kippur in Japan comes down to maps and lines. On our spherical Earth, when the sun is directly overhead and it is noon, the day is ending one-quarter globe to the east, while the same distance to the west, it is just beginning. If we are to have a calendar, at some point one must arbitrarily define a spot where the date changes abruptly. A single step to the east and January 1 becomes December 31.

In the nineteenth century, the empire on which the sun never set addressed this problem by drawing an imaginary international date line in the middle of the Pacific Ocean running from the North Pole to the South, directly opposite the globe from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich Park, London. Here and there the line meanders, generally reflecting the history of colonization as migrating peoples brought their date with them from the East or West. Jewish law, of course, does not go forth from London, and so rabbinic authorities have attempted to define a Jewish date line. The two main opinions at the time began with the assumption that Jerusalem is the center of the world. Rabbi Yechiel Michel Tucazinsky, a prominent rosh yeshiva in Jerusalem, set the dateline 180 degrees opposite Jerusalem. Rabbi Avraham Karelitz, the leading haredi authority of the time known as the Hazon Ish, argued that since noon in Jerusalem means sunset in China, the date line should be set at the eastern edge of the Eurasian continent. A third view held that there is no uniform date line, and Jewish law should follow the local date.

Japan lies to the east of the Hazon Ish date line but to the west of the line drawn by Rabbi Tucazinsky. The Jewish community in Japan had generally accepted the local reckoning of the date, but the Mirrer Yeshiva in exile was looking for a more authoritative answer.

Two days before Yom Kippur, the supplicants received a cable from Jerusalem:

In reply your cable 12/9 meeting rabbis my presidency decided you fast Wednesday Yom Kippur according the counting the days of the week current in Japan stop on my part I add none dare risk danger by fasting also Thursday but should eat that day.

Chief Rabbi Herzog

This decision was reached at a special summit convened in Jerusalem by Rabbi Herzog, which was attended by a number of great rabbinic figures (including Rabbi Tucazinsky) and boycotted by others.

Herzog explained that his decision was not actually a ruling on the question of the dateline per se. Deferentially noting that there were really only two people in the world knowledgeable enough to have a creditable opinion on the matter, the Hazon Ish and Rabbi Tucazinsky, Herzog did not feel qualified to decide between the two. As such, the matter should be deemed a safek (in doubt or indeterminate). Jewish law has decision procedures in such circumstances, and those are what he applied in this case.

However, another telegram had arrived in Kobe, this one directly from the Hazon Ish himself: “Eat on Wednesday and fast for Yom Kippur on Thursday, and don’t worry about anything.” Confusion ensued—some Jews fasted on Wednesday, some on Thursday, and some, to play it safe, on both days.

Some fifteen years later, Rabbi Herzog returned to the date line question. In the course of his deliberations, he discussed a classic eighteenth-century book on doubt in halakha: Rabbi Aryeh Leib Heller’s Shev Shema’tata. The copy he was using had once belonged to his beloved father and mentor, Rabbi Joel Herzog, who had been chief rabbi of Leeds and later of Paris. Herzog described discovering his deceased father’s handwritten notes in the margin of his book. But the words were cut off, midsentence. “Chaval al d’avdin,” Herzog laments, how unfortunate the loss, perhaps thinking not only of the words but of the man as well.

Herzog tried to reconstruct his father’s line of thought and suggested an epistemological distinction within the larger category of safek. There are uncertainties that are by their very nature unknowable, and there are those that could in theory be known but are not known now. Some things are unknowable; others are merely unknown. In the first case, there is greater room for leniency than in the second.

Herzog then wrote that the issue was too important to be left as a doubt, and the time had come to address the issue of the date line head-on. He considered the opinion of the Hazon Ish, which was based on an analogy to a related position first expounded by the twelfth-century Spanish scholar Rabbi Zerachiah Halevi of Gerondi. “This opinion,” Herzog wrote, “is built entirely on the premise that the top hemisphere of the Earth contains the land and all inhabitants, while the bottom is all water, with Jerusalem at the center of the top hemi-sphere.” As a modern, Herzog could not bring himself to accept this ruling. “Though I am but a thousandth of the dust under their feet,” he wrote of his rabbinic predecessors, he was unable to deny the obvious: “in reality this premise is erroneous.” Likewise, he saw no justification or precedent for “turning Jerusalem into our Greenwich” and setting the line 180 degrees opposite the Holy City, as Rabbi Tucazinsky had done.

Rabbi Herzog was an extraordinary Torah scholar firmly committed to halakha, yet also fully engaged in the modern world. He devoted much of his intellectual energy to striking a balance between the two.What, then, was Herzog’s final conclusion regarding the date line? We’ll probably never know. The last words of his lengthy responsum on the topic bears a note from the editor—“The manuscript abruptly ends here”—and continues “chaval al d’avdin.” Not only of the words but of the man as well.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

My Father and Birnbaum’s Heavenly City

According to one scholar, Uriel Birnbaum produced “more than 6,000 poems, 130 essays, 30 plays, 10 short stories, 15 fairy tales, fragments of a longer epic poem, 20 chapters of a lost novel and 30 collections of illustrations.” And yet, Birnbaum received little acclaim in his lifetime. Today he is all but unknown.

He Shall Not Press His Fellow

Once every seven years, the Torah says, the economic playing field should be leveled, and those trapped in debt should be freed. Even the rabbinic workaround reminds us of the ideal–as I was reminded after my startup foundered in the 2008 financial crisis.

Why I Defy the Israeli Chief Rabbinate

Everyone knows that the Israeli Chief Rabbinate is often capricious, needlessly adversarial, and hopelessly bureaucratic. Actually, it’s worse than that. It can’t be abolished any time soon, but its power should be radically diminished.

Chaim Grade: Portrait of the Artist as a Bareheaded Rosh Yeshiva

Grade attempted to perform the impossible: to undo in literature what had occurred in history and revive the dead of Jewish Vilna.

David Matar

Fascinating story told in such an engaging way. Am looking forward to Baruch and Judy Sterman's intellectual biography of Rav Herzog, that will capture the unique response of a great Jewish hero to the monumental challenges of Holocaust and Rebirth.