Origin Stories

The Jewish foundation story goes something like this: The Children of Israel were enslaved in Egypt, miraculously brought out by the God of Abraham and His prophet Moses, led to Sinai to receive the covenant, wandered in the wilderness, brought to the Promised Land where they established a monarchy and built a Temple, exiled to Babylonia after the destruction of that Temple, restored to the Promised Land, and allowed by the Persian king Cyrus—who had defeated Babylon—to build a new Temple. During the Hellenistic era, the brave Maccabees won independence against the encroaching Syrian Greeks, established the independent Hasmonean dynasty, and then lost that independence to the Roman Empire. Their descendants agitated against the Romans, then watched in horror as their rebellion was quashed, Jerusalem besieged, the majestic Second Temple burned, and thousands of Jews died of plague and starvation. Somehow, the Jews managed to reestablish themselves in the Galilee and consolidate a tradition that was centered on their holy scriptures and oral teachings, which would carry them through the difficult centuries ahead.

Like other origin stories, this compelling tale does not quite align with the facts of history. Strictly speaking, there were no Jews until the Second Temple period—the Pentateuch refers to the people who were redeemed from Egypt as the “Children of Israel.” The word Yehudi, which today is the standard Hebrew word for “Jew,” is rare in the Hebrew Bible and appears mostly in works composed after the period of Babylonian exile in reference to someone from the region of Judea, rather than to a follower of the Torah or practitioner of Judaism. The now standard Hebrew word for Judaism, Yahadut, is missing entirely from the Hebrew Bible and early Jewish sources. Regardless of what they called themselves, moreover, the religious practices of the covenantal people in the Hebrew Bible look quite different from those of the Second Temple and rabbinic periods. What makes the early Israelites and the Jewish people part of the same religion? And if the Israelites of the Hebrew Bible were not Jewish, when did Judaism begin?

Yonatan Adler’s recent book, The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal, considers these interlocking questions by probing the gap between Jews as we know them and their pre-Hasmonean ancestors. Adler argues that archaeological and literary evidence indicates that Jews did not begin to treat the Torah as an authoritative text until the Hasmonean era (roughly 140 BCE). Until then, Adler contends, the protagonists of the familiar Jewish origin story sketched above were not practicing Judaism, and, in an important sense that extends beyond what they called themselves, were not Jewish.

Adler’s book is part of the distinguished Anchor Bible Series published by Yale University Press, which often represents the scholarly consensus, but his argument is quite radical. Few ancient historians would subscribe to the traditional origin story sketched above, but many see signs of ancient Judaism arising centuries earlier, following the Judean return from Babylonian exile.

If his results are controversial, Adler’s approach is admirably clear and methodical. He opens each chapter with a review of the first-century evidence for Jewish observance, demonstrating that practices commanded in the Torah were widely followed in Judea in the first century CE. Adler then moves backward, looking for older artifacts and extrabiblical texts—what Adler calls “actual evidence”—which show that Jews were engaged in these same practices in earlier times, and he stops when he finds the earliest such evidence. For Adler, this establishes the origin point of a given practice, or the terminus a quo, to use the classical term.

Take Adler’s discussion of Jewish dietary laws. Archaeological digs of Roman-era sites in the southern Levant (an area roughly encompassing present-day Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan) have unearthed few pig bones. For instance, the former Givati Parking Lot in Jerusalem yielded “three significant Hasmonean-era faunal assemblages” with a total of 9,516 bones, only twenty-two of which were from pigs. Literary evidence from this period agrees. Roman writings mock Jews for their pork taboo, and the writings of the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria that defend it indicate that most first-century Jews kept some form of kashrut. In pre-Hasmonean sites, however, comparable evidence for such abstinence does not seem to exist.

Adler also argues that there is little compelling literary evidence that Judeans kept kosher before the Hasmonean period:

Outside the Pentateuch, texts that predate the middle of the second century BCE provide no indications that Judeans might have possessed any set of restrictions on their diet. The very few texts in the Hebrew Bible outside the Pentateuch which involve censuring individuals for eating certain foods invariably refer to cultic or ritual contexts—not to prohibitions that apply to ordinary diet.

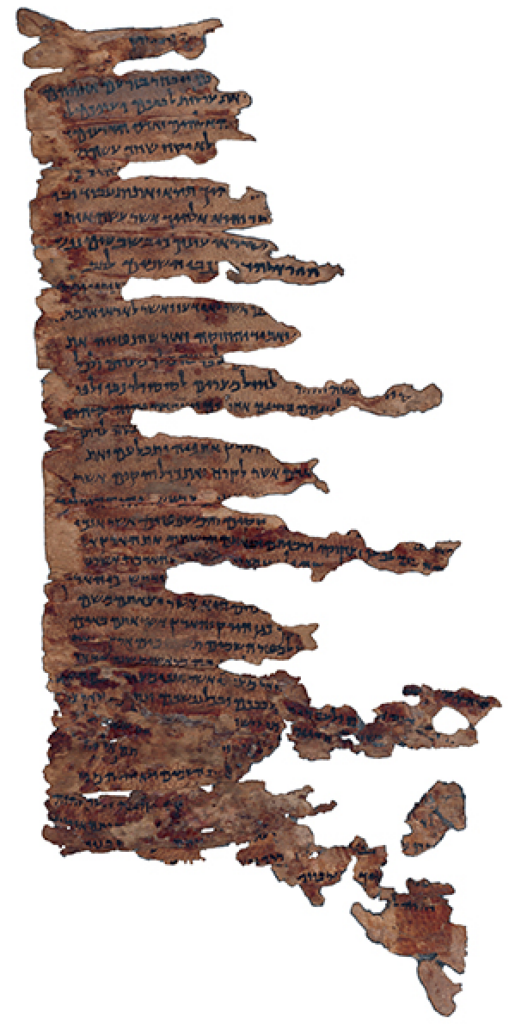

The same trend goes for the Judeans’ ritual practices. Archaeological evidence of Roman-era immersion pools is abundant throughout Judea and is confirmed in the Dead Sea Scrolls, but little archaeological evidence exists for Judean purity practices that precede the Roman era. Adler makes similar arguments about the practices of observing the Sabbath, wearing tefillin, fasting on Yom Kippur, celebrating Passover and Sukkot, and so on. The Torah, Adler argues, was simply not well known beyond “a small circle of Judean literati” in the Persian period and certainly was not viewed as authoritative.

The eighth chapter of the biblical book of Nehemiah recalls how Judeans who have returned from Babylonian exile ask the scribe Ezra to read from the Torah. Ezra reads a passage about the holiday of Sukkot, which inspires them to celebrate the holiday. Adler treats this passage as ideological fiction: “There is nothing in these narratives themselves,” he writes, “which suggests that the stories reflect any kind of historical reality.” Adler finds literary material from this period that was produced in Egypt as similarly unreliable. A cache of papyri and ostraca discovered on Elephantine, an island in the Nile River, includes a letter dated to the fifth century BCE addressed to Judean authorities that discusses the observance of Passover. Adler suggests, however, that this letter was speculatively reconstructed and misinterpreted by scholars overeager to detect traces of early Torah observance.

Persian-era documents that Adler dismisses may be more valuable than he suggests. Take the book of Tobit, a Judean novella that most scholars date to the third century BCE. The book opens with a first-person account of the protagonist’s piety, which includes this description:

After I was carried away captive to Assyria and came as a captive to Nineveh, every one of my kindred and my people ate the food of the Gentiles, but I kept myself from eating the food of the Gentiles. Because I was mindful of God with all my heart, the Most High gave me favour and good standing with Shalmaneser [the Assyrian king], and I used to buy everything he needed. (Tob. 1:10–13)

Adler doesn’t discuss this particular passage, but explains away other early texts that speak of abstaining from the “food of the Gentiles” as a reference to vague concern with ritual purity rather than the Torah’s detailed dietary system. Later in the book, Tobit washes himself before and after moving a corpse and burying it. In a footnote, Adler suggests that “the author of this text may have had in mind regular cleansing rather than ritual purification.” Yet Adler does not clarify why a bath would be important enough to include in an episode meant to demonstrate Tobit’s piety.

Ultimately, Adler dismisses nearly every pre-Hasmonean literary reference to the Torah as representative of an ideological elite. Yet it is notable, I think, that few Jewish texts survive from the Persian era in comparison to the Hellenistic era that followed it, and of the texts we do have, many are concerned with the importance of the Torah. The fact that these texts were preserved and transmitted is perhaps of more historical significance than Adler allows.

Adler treats Jewish literature produced in the first century as the top geological stratum in a mound of evidence for the origins of Jewish practices that show deference to the authority of the Torah. Ideas that developed over time and that united Jews from place to place, however, are of secondary interest. And while Adler looks for practices that he believes were viewed by their practitioners as rooted in biblical tradition, many Jews in the first century also observed practices that had little or no basis in the written Torah. Philo refers to such “unwritten laws” as ancient customs, as did the later rabbis. Yet if unwritten laws were of central importance at this time, why is Adler’s barometer of Jewish identity based on adherence to scriptural laws?

There is no question that the second century BCE was a time of significant change for Jews living in the Land of Israel, and this change is evident in a renewed emphasis on Jewish practices that have roots in scriptural tradition. But what makes the changes of the second century BCE the transition from Judean-ism to Judaism and not the series of similarly impactful changes that took place in the immediate wake of the Babylonian exile? Is it that the changes of the second century BCE bring us closer to the more familiar religion of the rabbis, while the changes of the sixth century BCE are closer to the world of the Israelites?

Adler’s study of Second Temple evidence through the lens of rabbinic practices depends on a set of assumptions concerning what Judaism is and what Judaism once was. But what if Adler had moved forward in time instead of backward? Suppose he had opened his study with an examination of early Second Temple sources and then looked at the development of both ideas and practices as he moved toward the first century CE. Had Adler opened his study by examining evidence from the Second Temple period, he still would not have found compelling evidence for circumcision, kashrut, and Shabbat. But perhaps he would have taken pause to address the many literary references to the Jerusalem Temple, charity, and prayer. He would have had to contend with texts that affirm God’s commitment to the people of Israel. He would have found references to covenant, monotheism, revelation, and the messianic age. Above all, he would have found texts that allude to and interpret scriptural traditions. All of these themes are featured in Judean literature of the Persian era, Jewish literature of the Hellenistic era, and later rabbinic literature. Indeed, they were so important that differences over them eventually led to the separation of Jews into sectarian groups in the early second century BCE.

Even if Adler made a compelling case for starting in the first century and moving backward, and privileging the search for practices over the search for ideas, he does not address the consequences of his choice to privilege archaeological evidence over literature. The artifacts that Adler studies come from the Land of Israel and thus can tell us only about life at the site where they were discovered. They tell us little about Jewish life in cities such as Alexandria, Antioch, and Rome, where Jews had lived for centuries by the time the Jerusalem Temple fell in 70 CE. A reader of Adler’s study could easily conclude that purity laws were a core feature of Jewish identity in the first century. In the diaspora, however, Jews who were devoted to their ancestral traditions may not have practiced these laws.

Such differences led Jacob Neusner and other scholars to conclude that multiple Judaisms existed in the Hellenistic era. Diaspora Jews of the time, however, might not have agreed. In the second century BCE, Jews living in Egypt enthusiastically responded to the Hasmoneans’ victory over the Syrian Greeks. To show support for their Judean kin, many Egyptian Jews began to give their children Hebrew names. And by the first century BCE, Jews in Egypt were sending so much money to support the Jerusalem Temple that the Roman orator Cicero complained about it. With the exception of sectarian documents, nearly all Jewish texts produced at this time refer to all Jews, wherever they lived, as members of a global community that share a common heritage, a common God, and a common messianic future.

When did these Jews start to believe that they were part of a global religion, and how did they define the particular features of Judaism? The answers to these questions are beyond our reach not only because of our limited data but also because they require us to make decisions about the ideas and practices that were most important to Jews. As Marc Bloch warns in The Historian’s Craft, the perusal of origins will inevitably be “put to the service of value judgments.” Projects such as Adler’s can, of course, help us discover significant links between earlier and later Jewish practices. But they also act as mirrors of the people whom we’ve become.

Suggested Reading

Inside-Out

The boundaries between the biblical canon and the Apocrypha have seemed firm for a long time. But what if the walls aren’t that solid?

In Praise of Humility

There are those who carry the quest for yichus to extremes; Steven Weitzman is not among them.

Purity and Obscurity

When contemporary Jews of priestly lineage avoid cemeteries, when ordinary Jews wash their hands before eating, or immerse themselves in ritual baths, they are acting according to the dictates of an ancient system.

Moses, Murder, and the Jewish Psyche

Sigmund Freud had always identified with Moses. At the end of his life, as the Nazis rose to power, he returned to the Bible and the origins of the Jewish psyche. We all know his scandalous theory—or do we?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In