Middlebrow’s Moment

In 1939, William Butler Yeats was placed on trial. The charge: spreading false ideas, namely the absurd belief “that art ever makes anything happen.” It was, of course, a made-up trial—Yeats was already dead. It was conceived by W. H. Auden, his fellow poet, who then famously declared that “poetry makes nothing happen.” For many, Auden’s statement was a goad: Can writing, in fact, change society? If poetry can’t, what about pamphlets, petitions, exposés?

Or, for that matter, bestsellers? The historian Rachel Gordan suggests as much in Postwar Stories: How Books Made Judaism American, which focuses on writers’ efforts to combat antisemitism and improve perceptions of Jews after World War II. At a moment when Jews comprised 4.5 million Americans, they faced a serious challenge: how to convince the other 135 million of their decency, normality, and respectability.The answer—at least one answer—was books.

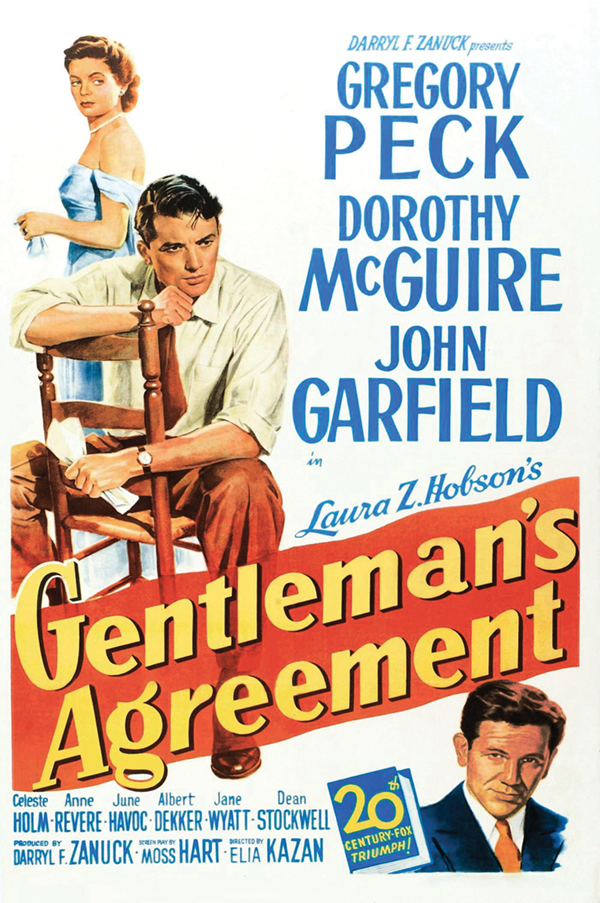

Somewhat improbably, their mission succeeded. Antisemitism declined, becoming taboo, and Judaism emerged as a major American religion. How that happened—and why it happened so rapidly—is Gordan’s subject. At the heart of her investigation are popular middlebrow books and articles about Judaism. It was, she writes, the middlebrow moment, when books like Exodus, Gentleman’s Agreement,and practically everything by Herman Wouk were widely popular. Fiction, said Kafka, should distress us, cracking the frozen sea within. These books didn’t. They were a warm bath, soothing and tame.

Turning our attention to middlebrow writers, and away from Bellow, Malamud, and the postwar Jewish-American canon, Gordan gives the impression of having discovered a major subject. Has she? Certainly she probes an intriguing historical riddle. What made Christian America surrender its sense of superiority, long a sort of birthright, after World War II? Was “middlebrow” a critical catalyst?

Gordan begins, as she must, with notes toward a definition. Middlebrow is slippery; as with obscenity, you know it when you see it. Beckett is highbrow. Steinbeck is middle. So were the Reader’s Digest condensed novels. For decades, elites shunned middlebrow—or pretended to. “It’s time to bring middlebrow out of its cultural closet,” insisted Tad Friend, who hailed its “siren call” in 1992. Friend’s exhortation—Down with shame! Up with middlebrow!—sounds quaint today: we enjoy what we enjoy, whether Proust or podcasts. But in the 1950s, highbrows took to the barricades attacking middlebrow.

If anything embodied middlebrow’s earnest, democratic spirit, it was Life magazine, the photo-packed mass-circulation weekly, which regarded Jews with anthropological interest. In 1952, Life put on its pith helmet to chronicle a strange Jewish rite, the bar mitzvah. Two years earlier, it published “What the Jews Believe,” a sort of CliffsNotes guide to Judaism. To many Christian readers, Jews were a dark continent. Life promised illumination.

Life’s forays into Judaica were something new. Before the 1940s, Jews rarely graced popular magazines, and antisemitism was a taboo subject for fiction. Then came a kind of glasnost. In 1945, Arthur Miller’s novel Focus assailed “race hatred in America” (as the cover delicately put it); two years later, the novel Gentleman’s Agreement featured a Gentile reporter in Jewish camouflage. As a Jew, he’ll investigate whether antisemitism exists (spoiler: it does). A major bestseller, it spawned a Hollywood blockbuster.

This was certainly a better sort of attention than Jews received previously. The 1930s was the height—or nadir—of antisemitism in America. Gordan describes the “barrage of antisemitism permeating American culture,” including, of course, literature. In 1938, just after Kristallnacht, many Americans expressed sympathy . . . for Germany. In the decade that followed, white Gentile America was still making up its mind about Jews.

Gordan captures well the paradoxical nature of Jewish life in America. As middlebrow Look magazine put it, to be Jewish was to “feel that you belong here in America—up to a point.” That point varied according to Jews’ visibility and social status, which was itself changing. Jews were outsiders becoming insiders—firmly planted but not entirely secure. Generally, Jews felt more accepted. Yet the scars of antisemitism remained.

A book could be written about those scars, and, in a way, Gordan has. Running through Postwar Stories is a delicate thread of emotions. It can read like a map of Jewish anxieties: about representation; about Christian judgments; about the state of the Jewish soul; about Jewish weaknesses. As a scholar, Gordan writes ambidextrously, both coolly and warmly; she covers events but also inner lives—“Jewish desires and imaginations.”

And those inner lives are frequently dark and shame-ridden. A middlebrow writer laments “how discrimination mangled the insides of a person.” A fictional protagonist worries, “Maybe it takes hurt to understand hurt, I don’t know.” A Jewish author suffers “the great wound of my youth” when rejected by Phi Beta Kappa. A reviewer blames “years of pogroms, sufferings and tortures” for Jewish angst. It was the condition of diaspora, “which implanted to us an inferiority complex.” And on and on.

To some degree, Jewish middlebrow was a response to these wounds. If antisemitism caused them, writing might soothe them. That meant boosting Jewish morale and stoking Jewish pride. And it meant attacking antisemitism, which hindered Jews socially and professionally and inspired self-loathing.

Exhibit A is Gentleman’s Agreement, whose author, Laura Z. Hobson, was the intense, restless daughter of Russian socialists (her parents, both avid writers, preached full assimilation: no accents, no foreign habits). In Hobson’s sunny worldview, prejudice is curable; bigots aren’t evil, only misguided; and antisemites need persuasion, not punishment. Show them their mistakes, and they’ll change. Her book was Christian in its attitude: first comes self-knowledge, then confession, penance, and absolution.

Gordan makes no claims for Hobson’s novel as literature. Clearly, this was no Middlemarch, but even without graceful prose or psychological depth, it appealed to readers. Some feasted on America’s flaws, enjoying “the pleasure of castigation” (Gordan’s fine phrase). Others wanted to join a righteous club. As Gordan puts it, “They liked liking Gentleman’s Agreement.” This was Truman-era virtue signaling—reading the right novel and flaunting it.

Only one thing was missing from Hobson’s novel: actual Jews. The book was essentially propaganda (“propaganda of the most artful kind,” a critic noted). If readers wanted to know about Judaism, they had to look elsewhere—to a popular genre Gordan calls “Introduction to Judaism.”

In effect, these introductions began where Hobson left off. One of the more popular was Rabbi Milton Steinberg’s Basic Judaism (1947). The rabbi’s simple, noble mission was raising Jewish morale through religious literacy. Steinberg claimed to find Judaism and America fully compatible. “Both are democratic,” he insisted. “Both emphasize the worth of the individual and his right to freedom.” That pleasing message—an instance of what Jonathan Sarna calls “the cult of synthesis of American Jewish culture”—found a large, ecumenical audience.

Not as large, however, as Life magazine, with its 13.5 million readers. Gordan’s chapter is a reminder that not all “Introductions” were high minded or mission driven, except insofar as the mission was to sell magazines. When Life’s editors assigned articles about Jews, they gave Jewish writers a dilemma: how to write honestly about Judaism for a largely Christian audience. Their answer? With finesse. Like Hobson, they sought to subtly (or not so subtly) define Jews in narrowly religious terms, not racial ones.

It proved a smart strategy. Race was fixed, unalterable, and triggered xenophobia. Calling Jews a religious community put them on equal footing with Christians and satisfied the first requirement of public life in America: have faith. It was the 1950s, when “under God” and “in God we trust” were added to stamps, currency, and the Pledge of Allegiance. Thus, a Christian nation became “Judeo-Christian.” The alliance was enshrined in Will Herberg’s landmark Protestant, Catholic, Jew. Never mind that Jews were only 3 percent of the population. In Herberg’s book, they were one-third of America’s religious triad.

Gordan’s brief for middlebrow writing rests mainly on its utility. It wasn’t artful. It wasn’t elegant. It didn’t capture a nuanced, shaded reality. But it was effective. People consumed it avidly, seeking knowledge and self-betterment. In the case of the Judeo-Christian tradition, they embraced a useful fiction. That little hyphen did a lot of work, erasing significant differences.

Yet the problems with middlebrow were also obvious. The “middlebrow moment” was also the “arguing-about-middlebrow moment.” The opening salvo was Clement Greenberg’s 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” which deplored the “dumbing down” of high culture. Twenty years later, the highbrow hatchet fell again. Leafing through Life, Dwight Macdonald spotted a Renoir, then a horse on roller skates. Nothing wrong with the Renoir. “But that roller-skating horse comes along, and the final impression is that both Renoir and the horse were talented.”

Macdonald could acknowledge middlebrow’s power, much as Marx respected capitalism. Still, he found it dreadful. It wasn’t just boring (the Saturday Evening Post was “the sort of magazine that was read by Richard Nixon’s mother,” one journalist said). Macdonald’s strongest objection was his simplest: Middlebrow isn’t true. It simplifies and falsifies. It violates the reality principle.

At times, Gordan seems untroubled by this, but her feelings can be hard to discern. At a 2018 lecture, a questioner noted a disturbing quality to popular Judaism primers: “It’s hard not to interpret this story as a kind of neutering of Judaism in order to be accepted.” Gordan nodded vigorously. “You put it so beautifully,” she said. In her book, she concedes that “a thorny mess of midcentury myths” was handed down and that “each generation’s maturity is achieved, in part, by recognizing lies propagated by preceding generations.”

That deception, she admits, came from a good place—a desire for equality and acceptance in America. The price of admission was a kind of erasure. As Gordan writes, “In Hobson’s fictional world, no religious, noisy, or angry Jews need apply.” It often went beyond that. Jews couldn’t appear too smart or ambitious, too radical or successful, too homely or infirm. They couldn’t be noisy (being shtum was fine). Life’s 1950 article painted a rosy picture: “the respectable man at his ease in respectable society.”

Naturally, many serious Jews recoiled from this. Some decried the “Judaism made easy” approach. (“Judaism is not easy,” one reader objected. “No serious way of life is.”) Among the loudest dissenters was Herberg himself. In his view, Life offered a bland, bourgeois Judaism, bereft of “authentic Jewish faith” and deaf to the poetry of existence. Real Judaism was complex and challenging. It was Kafka’s axe, not Reader’s Digest.

To her credit, Gordan includes this debate, and she acknowledges that the highbrows were essentially right. Though it barely needed saying, Jews were not, in fact, just like Christians. They had a different experience, a different history, and even the most wayward Jews carried that history with them. Some had abandoned Judaism but were defined by what they rejected. Many were shaped by the experience of exclusion. Being treated differently had made them different—profoundly so.

Gordan doesn’t dwell on the psychic cost of pretending to be something you aren’t or the resentment Jews would naturally feel toward a dominant Christian culture. Yet she does suggest that these identity contortions came with a cost. In the name of Jewish dignity, Jews assumed some undignified positions. Gordan describes various Jewish efforts “to pitch themselves to an American audience.” In so doing, they reduced themselves to a product, with Christians as gullible consumers.

In Gordan’s telling, Jewish middlebrow writers were often terribly constrained. Life knew what it wanted and, more pointedly, what it didn’t: Zionism, politics, or anything “defensive.” Unless a Gentile reader “accepts it and warms to it,” an editor worried, “the article is a failure.” Life’s attempt to find a Jewish writer without any grievances who would render Judaism sympathetically can seem grimly comic today. But it was normal for 1950.

Improbably, Life’s experiment succeeded. The editors approached a Reform rabbi, Philip Bernstein, who had a sideline in magazine writing. He gamely agreed, and his article was something of a coup: it honored Judaism’s spirit and diversity, with some simplifying. As Gordan notes, “The essay portrayed Judaism cautiously, and with Christian expectations in mind.” The reaction was mostly, if not entirely, positive, and the article served its purpose: education and uplift. The article “contributes more to decent self-respect among the Jews,” one reader crowed, while Time magazine saluted its “cheerfully humanistic” Judaism. It was left to highbrows to object. This wasn’t Judaism, Herberg sighed; it was feel-goodism: Judaism crossed with The Power of Positive Thinking.

These debates over Jewish middlebrow—a family argument—are at the heart of Postwar Stories. Yet Gordan’s story of middlebrow and its discontents doesn’t abandon its thesis: that these popular books and articles altered how Gentiles perceived Jews and how Jews perceived themselves.

This is easy to suppose but harder to prove. Yes, millions read Life, but often casually; for many, Life was like a quick lunch, consumed and forgotten. As for Gentleman’s Agreement, everyone seemed to think it was for someone else. To highbrows it was for middlebrows. To Jews, it was for Gentiles. A Christian minister thought “it might jolt some of our benighted Christian brethren out of their complacency.”

Like that hopeful minister, we might wish reading improves character while harboring some doubts. Books can inspire outrage—burnings, bannings, the odd fatwa—quite easily, while kindness seems harder to inculcate. And the worst books about Jews—The Clansman, The International Jew, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion—are dreadfully durable, like antisemitism itself.

If middlebrow helped change attitudes (and let’s assume it did), what else played a role? One can point to liberalizing trends in America and the effect of 550,000 Jewish soldiers serving alongside Gentiles in WWII. Also notable was the rise of the Jewish middle class. Wealth conferred status; status brought respect. As Jewish immigrants aged, a young, striving generation, vastly more assimilated, assumed its place. These younger, wealthier Jews were more readily embraced as Americans.

Another important factor, Gordan points out, was the rise of Nazism. It not only inspired sympathy for Jews as victims; it discredited racialist antisemitism. For Americans, rejecting German fascism meant rejecting American antisemitism. Yet Gordan is careful to note the fragility of the Jewish-Christian alliance. Opposing antisemitism didn’t mean liking Jews. Often, it meant toleration, a lower bar, though acceptable given the times.

In general, Postwar Stories makes fine and smart company. Gordan’s métier is middlebrow; she’s on shakier ground with intellectuals, especially those haughty highbrows, the New York intellectuals. They get cursory treatment here, and the children of Marx (Adorno, Horkheimer, et al.) are entirely absent. That said, Gordan’s writing is free of academic jargon, and she has a gift for weaving together history, character, and insight, while teasing out the emotional dimension of a story. Gordan admires cheerful uplift but is powerfully drawn to darker, messier realities, which gives her book weight and gravity.

She also conveys, more subtly, how events might have unfolded differently. History can seem like a series of accidents, but up close, it seems less random: specific people making specific decisions. Gordan cites Lila Corwin Berman’s claim that Jewish PR was “a political necessity.” Was it? Certainly it was understandable, but one can imagine different strategies, different decisions. The arc of history is long, and it zigs and zags all over the place.

Indeed, Gordan shows how it might have zigged (or zagged) differently. Back in 1923, a distinguished Hebraist, Israel Davidson, cautioned against offering “too many explanations” to Gentiles. “Friends do not need them,” he wrote, “and enemies would not believe them.” Two years later, Elliot Cohen, the future Commentary editor, made the same point: American Jews shouldn’t despise or defend themselves. “American Jewry must be made to see that a life of apology is a shameful apology for a life.”

It’s tempting to sort Gordan’s vignettes into two categories: profiles in courage and portraits of compromise. While middlebrows peddled a simple, soothing Judaism, others offered a more dignified path. “Assimilation as a method of adjustment is totally bankrupt,” the author Ludwig Lewisohn insisted. Instead of timid, meeching Jews, anxiously camouflaged, he wanted proud Jews, calmly standing apart.

Of all the paths untaken, the most bracing was Hobson’s—the younger Hobson’s. Before Gentleman’s Agreement, she wrote an article shocking in its force and fury. “You can drown us, shoot us, poison us all and have done forever with the Jewish problem,” Hobson wrote, addressing herself to a Christian nation that failed to banish antisemitism. “Go ahead,” she dared them, “get on with it.” Naturally, her fiery j’accuse was rejected by Time. Far too angry. For Jews, such incendiary outbursts were forbidden. The path of righteous Jewish anger was closed for the moment.

It wouldn’t be closed forever. By the late 1950s, the “middlebrow moment” had passed. Indeed, it seemed obsolete. The 1960s liberated a long-festering Jewish anger, as Jewish artists gleefully demolished the model-minority myth. Suddenly, there were angry Jews; lustful Jews; Jews with complex, messy lives; even indignant Jews. This was the Allen Ginsberg–Lenny Bruce–Philip Roth era. The culture had caught up to Laura Hobson.

In a way, “middlebrow” is a fairly good peg on which to hang a larger, more interesting story about Jewish Americans. By the 1970s, shame was out. Jewish literature was flourishing. “If any group is to be pitied, it is perhaps the ‘Wasps,’” Alfred Kazin declared in 1972. Even before then, Robert Lowell had complained that “Jewishness is the theme of our literary culture,” supplanting midwestern and southern writing.

A middlebrow book might end here, on a cheerful, triumphant note. In real life, such “closure” eluded Jewish Americans. Gordan tells the story of a group limping toward a sort of freedom—not legal freedom, which Jews already enjoyed, but spiritual freedom: freedom, within the normal human constraints, to be one’s true self without excessive shame. “Perhaps it would be the century that broadened and implemented the idea of freedom, all the freedoms,” says the hero of Gentleman’s Agreement.

That hopeful spirit animates Postwar Stories, with its army of wounded souls longing to have their pain recognized. In a sense, that’s what Gordan has done, while paying respectful attention to neglected middlebrow writers. Gordan’s boldest stroke is taking middlebrow seriously, insisting it mattered and matters still. Her book suggests that Jewish middlebrow’s noblest mission wasn’t changing Christian minds but salving Jewish wounds.

In one of her final chapters, Gordan describes an Orthodox woman, a Holocaust survivor, who happens upon a 1955 Life magazine story about frum Judaism. For the first time since fleeing Poland, she feels recognized, respected. Gordan captures her excitement: “To see a Jewish lady lighting candles on the cover! It meant that a Jewish life was worth something in America. Even more stunning, it meant that the life of a Jewish woman mattered.” It’s a beautiful moment, and Gordan holds it up to the light.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Revisiting Herman Wouk’s City Boy

Remembering Herman Wouk's "gentle mockery at the shopworn pretensions of bohemian poseurs and ethnic Jews passing as nonhyphenated Americans."

Another Round with Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer had the gift of enlivening everything he touched. And he touched almost everything, from politics to Hollywood to Sports. But his Jewish novel stayed in the drawer.

Bellow, His Biographers, and the “Quivering Schmucks”

Many authors have passionate readers, but few have drawn as many self-consciously nutty fans as Saul Bellow.

Eden in a Distant Land

A new biography of Abraham Cahan unpacks how a young immigrant from Lithuania created the Forward and changed American Jewry.

ann powwell

For all his subtle disdain, Jesse Tisch's final paragraph got it right: Even the bestsellers that appealed to readers beyond the Jewish world, were, at bottom for Jews. And they spoke to some of us in ways beyond what is now credited to them.

Reading "Gentlemen's Agreement " as a teenager inspired me to resolve to speak up in situations in which self-interest or politeness were the more desirable option . It also sensitized me to the subtle antisemitisms that the Jewish world in which I lived were inclined to tolerate, if not ignore. Jews more sophisticated than Tisch's "middle-brow" ones tolerated "The Death of Klinghoffer," overlooked the antisemitism in Spike Lee films, endured ethnic and DEI studies that embraced every minority except Jews, and never spoke up as the heroine of "Gentlemen's Agreement " finally did. Turns out, the

"sophisticated " Jews never learned any lesson from "Gentlemen's Agreement, never even making it to "middlebrow" understanding.