Revisiting Herman Wouk’s City Boy

Herman Wouk, who died May 17 at age 103, would not make most critics’ shortlists of great American postwar novelists—or even Jewish American ones. At a time of literary experimentation, his prose style and plot structures were conventional if not downright retrograde; in an era of radical critique, his sensibility was one of bemusement rather than outrage. His was not the voice of the jeremiad against postwar suburban conformity but of gentle mockery at the shopworn pretensions of bohemian poseurs and ethnic Jews passing as nonhyphenated Americans. Wouk, whose name is pronounced “woke,” was anything but.

Yet, as literary historian Leah Garrett points out (citing a 1955 Time cover story on the bestselling author), though Wouk’s novels rejected the dominant trends in recent U.S. fiction of “skeptical criticism, sexual emancipation, social protest and psychoanalytic sermonizing,” Wouk was not only a popular author but also a surprisingly innovative one. Without ideological fanfare, his works injected the New Deal and Popular Front agenda of ethnic pluralism into a new, more inclusive definition of American patriotism, one that gently edged WASPs from their pedestal without violently overturning it.

It was Wouk’s insertion of Jewishness almost seamlessly into the postwar American tapestry that constituted his signal achievement. Even his breakthrough work, the 1952 Pulitzer Prize–winning The Caine Mutiny, managed to derive a counterintuitive Holocaust lesson from the admonition to “just follow orders”—even when issued by irrational, shaky authority. Jewish naval lawyer Barney Greenwald, after he had won the acquittal of the court-martialed officers who had seized command of a ship from its incompetent and evidently insane captain, said American soldiers “going by the book” was precisely what saved his “little gray-haired Jewish” mother from being “turned into soap” by the Nazis.

The Caine Mutiny was sandwiched between two far more overtly Jewish novels by Wouk. Still remembered today in part through the film version in which Natalie Wood embodied its beautiful eponymous Jewish heroine, Wouk’s subsequent effort, the bestselling 1955 novel Marjorie Morningstar, intertwined the midcentury subcultures of Upper West Side affluence, downtown bohemianism, and summer stock theatrics in a manner that highlighted their Jewish inflections without either sentimentalizing or burlesquing them.

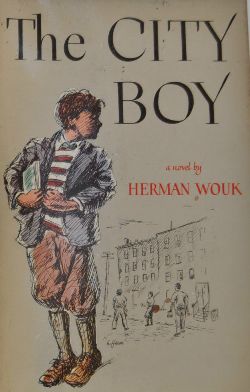

Less well remembered but perhaps still more deserving of reacquaintance today is Wouk’s second novel, City Boy: The Adventures of Herbie Bookbinder. A small comic masterpiece that has been accurately described as an urban Jewish Tom Sawyer, City Boy is a classic of the young adult genre avant la lettre. As with Marjorie Morningstar, the fact that the action takes place in a thickly Jewish environment is both essential and inconsequential to the book’s enjoyment. Eleven-year-old Herbie is a universal type: diminutive, overweight, bookish, and unathletic, yet a true boy nonetheless, whose quest for the pretty red-headed fille fatale, Lucile Glass, drives him to acts of foolhardy bravery and reckless derring-do we would otherwise not expect from such an apprentice schlemiel.

Herbie grows up on Homer Avenue in the largely Jewish Castle Hill section of the Bronx, the son of an upright, scrupulously honest ice manufacturer. He is a romantic who finds himself periodically consumed by a new feminine object of adoration. It is on the rebound from a jilting by his teacher at Bronx Public School 50—the former Miss Diana Vernon, now unaccountably transformed into Mrs. Mortimer Gorkin—that Herbie first sets his sights on young Lucile:

Her starched, ruffled blue frock, her new, shiny, patent-leather shoes, her red cloth coat with its gray furry collar, her very clean knees and hands, and the carefully arranged ringlets of her hair all suggested non-squeaky loveliness. At the moment of his so deciding, it chanced that she turned her head and met his look. Her large hazel eyes widened in surprise, and at once there was no further question of candidacy. She was elected.

Discovering that not only Lucile but his archrival for her affections, Lenny Krieger (Esau to Herbie’s Jacob), will be spending the summer at Camp Manitou, perched in the Berkshires, Herbie declares his intention to join them there, even so much as voluntarily entering the office of his school principal—an act hitherto unheard of for either pupil or teacher—who also happens to be the camp’s owner and director. Mr. Gauss requires no further provocation and, through his trademark flattery and flummery, manages to persuade Herbie’s parents to cough up the $300 per-child fee to enroll both Herbie and his big sister, Felicia, for the coming season.

That summer camps have served as vital institutions for assimilating Jews while simultaneously perpetuating their distinctiveness has not been lost on students of American Jewry. That the Jewish summer camp experience, an object of much nostalgic rhapsodizing by its myriad veterans, was in truth often a rather unpleasant and typically unromantic experience—at times even a cruel one—will be admitted by the honest among us. Perhaps no book captures this peculiar amalgam better than City Boy.

Camp Manitou is a dilapidated construct built and maintained on the cheap by the penurious Gauss with the sole design of supplementing his modest educator’s income. A character straight out of Dickens, Gauss possesses an uncanny knowledge of how far he can minimize expenditures on his charges while maximizing their chances for reupping the following summer. In the long, tedious intervals between strategically timed highlights, like color wars or fireworks night, campers and owners “glared at each other, so to speak, over the sack of money which the parents had provided, and in which lay the possibilities of happiness for both; and every time one side drew a benefit from the bag the other side suffered.”

Manitou is Jewish in an equally calculated way:

In his visits to parents [Mr. Gauss] raised no religious questions. He had observed that strict Jewish parents brought up the topic at once, and their children were lost to him in any case, since the Manitou kitchens did not at all follow the Mosaic food laws. The others, from whom he drew most of his campers, were satisfied with a few words in the booklets about “beautifully inspiring services each Friday evening under the shining Berkshire stars.” The timing of worship on Friday night instead of Sunday morning was adequately Hebraic for his purpose.

Wouk does not make Gauss himself a Jew, possibly because few Jews had attained the office of public school principal by the late 1920s, when the story is set, or possibly out of fear that doing so would render him too close to being an anti-Semitic stereotype. But it is certainly apparent that Gauss is a thoroughgoing urbanite otherwise out of place in the bucolic Berkshire setting. “Had he been found unconscious and naked in a forest,” Wouk quips, “he would have been identified at once as a New York City principal who owned a summer camp.”

City Boy is a testament to Herman Wouk’s comic genius, his satiric wit, and his narrative aplomb. The story races to a suspenseful climax, too convoluted and improbable to summarize here but nevertheless entirely convincing and mesmerizing for the charmed reader. At the same time, the novel is not without its serious side. Young Herbie does triumph over adversity in the end—the scholar Bookbinder vanquishing his nemesis, the truculent Krieger—but this is no Revenge of the Nerds. The camp’s homespun handyman, Elmer Bean, in the midst of an extraordinary goodbye in which he advises Herbie and his cousin Cliff not to let Gauss hoodwink them into returning the following year, offers the hero only his mixed endorsement: “Herb—I dunno what to tell you, Herb. You might be a very big guy someday, an’ then again I dunno.” Herbie has employed deceit and theft to win the day—and the heart of his fair lady. Before the book’s end, he must at last confront the real ethical hurdles to his becoming a true mensch.

What it took to become a mensch remained one of the abiding themes of Herman Wouk’s fiction over the many decades after the publication of City Boy. It was certainly what he was thinking about when he wrote in his enduringly popular This Is My God that “the core of Judaism is right conduct to other people.” What has been labeled Wouk’s conservatism was more accurately an ethical commitment that rooted his fiction in a quest to transcend human foibles even as he took great relish in exposing them.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Jake in the Box

The patriarch Jacob was the father of twelve tribes and (eventually) fêted by Pharaoh. But, as Yair Zakovitch shows, the Bible does not portray a happy man.

Questioning in the Darkness

A century ago, S. Ansky (Shloyme-Zanvl Rappoport) assembled thousands of questions for a survey directed at shtetl residents in the Russian Empire's Pale of Settlement. A new book examines this fascinating survey.

Purim at JRB

This Purim at the Jewish Review of Books, we’re turning things a little upside down. A Jewish review of books? Why stop there? We’ve collected three fun and funny reviews…

The Great Family Circle

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, “the father of modern Hebrew,” famously raised his own son to be the first child in almost 2,000 years to speak only Hebrew. When Itamar Ben-Avi grew up, he was fascinated by . . . Esperanto. Esther Schor’s new book on L. L. Zamenhof, his would-be universal language, and those who still speak it inspired Stuart Schoffman to revisit the oddly parallel careers of Ben-Yehuda and Zamenhof.

David Fried

I was delighted to read this piece. I ran into "City Boy" by accident in the library a couple of years ago and enjoyed it a great deal. despite the "Herbie saves his Dad's business!" heroics at the finish. With Wouk, though, period is everything. Folks are nostalgic for the Jewish summer camps of the Fifties and later--what things were like in the Twenties you have to be 103 to remember. Similarly, people forget that "Marjorie Morningstar" is a satire of the Thirties, looking back from mid-century. I read it a long time ago, but remember thinking how much was lost when Dwight MacDonald's despised Midcult met its end.