In Memory of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

April 1948 was the fifth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The Central Committee of Polish Jews had asked Vasily Grossman, Ilya Ehrenburg, and five other members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee to attend the opening ceremony for a monument honoring the fighters. Discussions between the two committees went on for some time, but Viacheslav Molotov, the Soviet minister of foreign affairs, eventually ruled against the Soviet delegation attending the ceremony. Not only was Grossman unable to go to Warsaw, but he was also unable to publish the impassioned essay he had drafted for the occasion. The Russian text was only published more than seventy years later in 2020; it is translated into English here for the first time.

From 1943 to 1946, along with fellow war correspondent and writer Ehrenburg, Grossman had worked on The Black Book, a collection of eyewitness accounts of the Shoah on Soviet and Polish soil. It was canceled by the Soviet authorities in 1947, and the book plates were destroyed. The official Soviet line was that all nationalities had suffered equally under Hitler. Acknowledging that Jews constituted the overwhelming majority of those shot at the many execution sites in the Nazi-occupied Soviet Union would have led to the acknowledgment that other Soviet citizens had been complicit in the genocide. In any case, Stalin was, by then, actively encouraging and exploiting antisemitism.

In 1943, Grossman had published his first fiction about the Shoah, a short story titled “The Old Teacher.” After the war he rewrote it as a play for the Moscow State Jewish Theatre. Struggling to meet the authorities’ ideological demands, he reworked it twice, but in the end it was neither published nor staged. Solomon Mikhoels, the theater’s director and a friend of Grossman’s, had been slated to play the lead role. In January 1948, he was assassinated on Stalin’s orders. Only a man of Grossman’s courage and determination would have attempted to publish an article about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising at such a time.

Vasily Semyonovich Grossman was born in 1905 in Berdichev, a Ukrainian town that was home to one of Europe’s largest Jewish communities. His parents, however, were highly Russified, and he had little Jewish education. After beginning his higher education in Kiev, Grossman transferred to Moscow State University to study chemistry. He soon realized that his vocation was literature, but he was obliged to complete his degree. He worked for two years in the area of Ukraine known as the Donbas as a gas-analyst in a coal mine and then as a chemistry teacher in a medical school. In 1934 he published a short novel, set in the Donbas, and a short story, “In the Town of Berdichev,” which won the admiration of Isaac Babel, among others.

The true nature of Grossman’s—or anyone else’s—political beliefs in 1930s Russia is hard to ascertain. On the one hand, many people close to him were arrested or executed at the time. And Grossman certainly had at least some sense of the magnitude of the Terror Famine in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933. On the other hand, he had literary ambitions, and all writers were dependent upon the Soviet regime. It is possible that, like others during this period, he may have still hoped that the Soviet system would keep its revolutionary promise.

All we can say for sure is that the distinction between the “establishment” writer of the 1930s and 1940s and the “dissident” who wrote the great novels Life and Fate and Everything Flows in his last fifteen years is essentially one of degree. Even Grossman’s first novel, little read today, evidently once had the power to shock with its honesty; in 1932 Maxim Gorky criticized it for “naturalism” and suggested that Grossman should ask himself, “Which truth do I wish to triumph?”

Along with Ehrenburg, Grossman was one of the best-known Soviet war correspondents, famous, above all, for his articles about the Battle of Stalingrad. The Soviet victories of 1943, however, brought him not only joy but also unimaginable pain. As the Red Army advanced west during 1943, Grossman learned in detail about the mass executions of one and a half million Jews carried out in Ukraine from August to December 1941 and during the summer of 1942. His mother was among them, and he was racked with guilt because he had failed to get her to leave Berdichev at the war’s outset. After Grossman’s death, an envelope was found among his papers with two letters he had written to his mother on the ninth and twentieth anniversary of her murder.

Grossman’s first article about the Shoah, “The Murder of Jews in Berdichev,” was not published during his lifetime. Another article, “Ukraine without Jews,” was published only in part. He was, however, able to publish “The Hell of Treblinka,” one of the first substantial—and most searing—accounts of the workings of a Nazi death camp in any language. It was safer to discuss the death camps in Poland, since the issue of collaboration on the part of Soviet citizens did not arise so acutely.

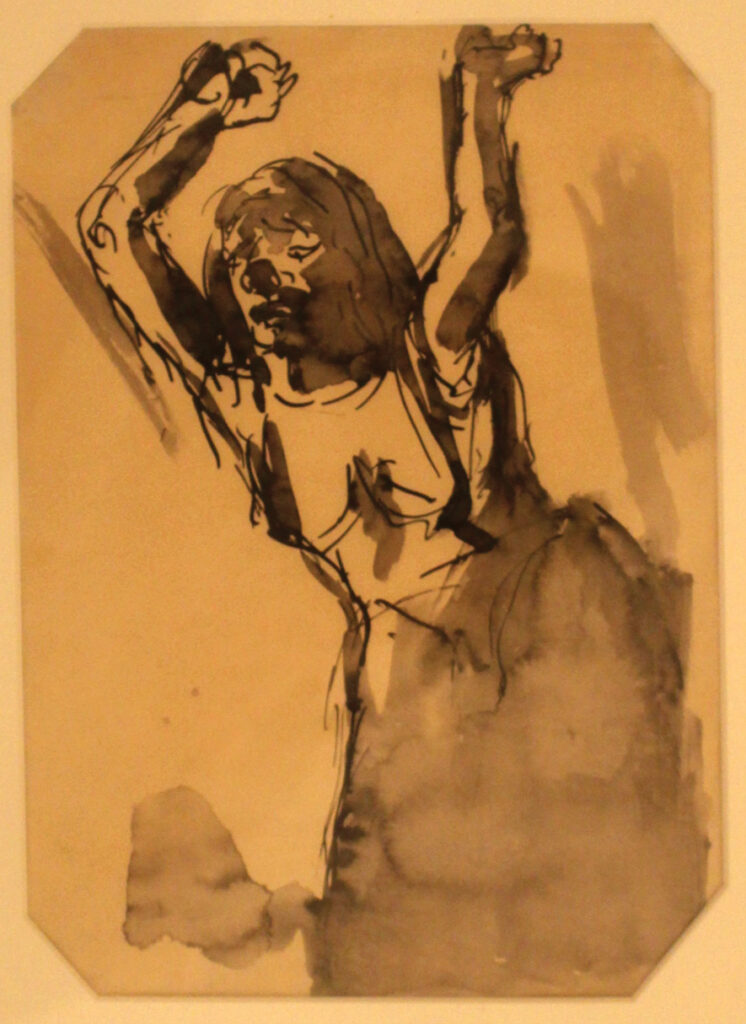

Unlike his earlier writing about the Shoah, Grossman’s unpublished Warsaw Ghetto essay is not the work of a journalist. Rather, he adopts a poetic, allusive mode in this vignette about visiting the ghetto after the Soviet Army had liberated Warsaw. He characterizes the barbed wire on the ghetto wall as a “crown of thorns,” and describes the uprising as lasting “forty days and forty nights.” (Grossman’s editor changed this to “forty two,” probably to eliminate the biblical echo for the censor; in fact the uprising lasted twenty-six days.)

In his 1945 notebook, Grossman described seeing a worker from a Łódź stocking factory with “the face of a living corpse” returning to the Warsaw Ghetto. In his 1948 essay, the worker becomes an emblematic, almost mythic figure:

Short and narrow-shouldered, with sunken cheeks covered in dark stubble, this man was wearing a long, ragged robe and carrying a child’s basket made from colored straw. . . . He was about to leave Warsaw for Łódź and he had entered the ghetto to collect a handful of gray ash from beneath the wall where the SS had burned the insurgents’ bodies; he was taking this ash back with him to his home city.

Although Grossman was not very conversant in Jewish culture, many readers would have sensed an allusion to a story of the Ba’al Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, who once saw a simple stocking maker walking to synagogue and described him as laying the foundation for the future redemption.

Grossman describes this stocking maker as a “Chaplinesque figure,” though this line was deleted by his editor. It’s a curious description, but Ehrenburg once wrote that “Charlie Chaplin—the Tramp, the Charlot, of Europe—not only made people laugh; he also defended them. Yes, it was a comedian—not sages and philosophers, not the West’s exalted institutions—who stood up for humanity.” (Chaplin was also sometimes rumored to be Jewish.) Like Grossman himself, the quiet stocking maker is honoring both his conscience and his fellow Jews who died in the battle for freedom. Grossman’s transformation of this man he first saw as having “a face like a corpse” into a “Chaplinesque figure” and “a symbol of the living memory of the people” is itself a moving profession of faith and hope.

As we have noted, Grossman’s well-meaning editors tried to make this article more ideologically acceptable to the authorities through various small changes. These interventions are an interesting illustration of Soviet editorial practices, so they are included in the following text in square brackets.

This translation follows the text published in 2020 in the journal Voprosy Literatury (Questions of Literature), no. 2. The original typescripts are held in the archive of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee.

On the [glorious] day that the Red Army liberated the capital of Poland, I crossed from the suburb of Praga into Warsaw itself. Praga, on the east bank of the Vistula, had seen long, relentless fighting; nevertheless, compared to the tragic remnants of Warsaw, it seemed to have escaped lightly. It looked intact, almost unharmed. Warsaw itself was all ruins: buildings gutted by fire; gaping eye sockets instead of windows; torn cables; steel tram rails wrested out of the ground; bonfires lit among [once beautiful] squares and streets; crowds of people with no roof over their heads.

It seemed at first that this marked the peak of the destructive frenzy of Fascism. But when I entered the Warsaw ghetto—when I slipped through a gap in the brick wall, beneath its barbed-wire crown of thorns—I saw a picture of destruction unlike anything I had ever seen before. Here were no gaping windows or skeletons of buildings. No fires were burning on squares or streets; no homeless people were warming chilled hands by smoky flames. There was only a dead, frozen sea of shattered fragments of brick, only silence over cold, empty stone. The soldiers of the Warsaw Ghetto were lying deep beneath hundreds of tons of frozen stone. For forty days Warsaw had shaken beneath the thunder of guns, the explosions of bombs, the grinding of tanks, and the grating of repeated bursts of machine-gun fire.

The men, children, and women of the Warsaw ghetto uprising fought for forty days against the regular infantry divisions of the German-Fascist army; they [the rebels’ combat battalions] went into the attack, broke through the Fascist lines [broke through from the ghetto into the depth of the Warsaw streets], fought off tank columns, and withstood heavy bombing. This battle lasted forty days and forty nights.

And I was overwhelmed by grief. When a battle ends, I said to myself, its reality continues to live in the hearts of the fighters, in their memories and stories. They carry within them all the heat, all the flame, all the passion of the battle; the battle lives on in their memory and in their eyes. But here in the ghetto there are no survivors. Who will tell of these great days of suffering and glory?

I walked for a long time among the silent ruins before I met another human being. Short and narrow-shouldered, with sunken cheeks covered in dark stubble, this man was wearing a long, ragged robe and carrying a child’s basket made from colored straw; his large, dark-brown eyes were filled with the precious moisture of sadness and thought. He was about to leave Warsaw for Łódź and he had entered the ghetto to collect a handful of gray ash from beneath the wall where the SS had burned the insurgents’ bodies; he was taking this ash back with him to his home city. I watched him for a long time as he walked away—a small Chaplinesque figure moving alone through the winter fog, among mute stone, his round child’s basket quietly swaying to the rhythm of his steps. It seemed that this small man, whose name I do not remember, who had survived by a miracle and who wanted to pay homage to the memory of the fallen, was the first person to enter the ghetto since the city had been liberated.

And now, on the fifth anniversary of the uprising, this small, ragged figure—the Łódź stocking maker carrying a handful of ashes in a straw basket—seems to me a symbol of the living memory of the people, which has inscribed for all eternity the proudest and bitterest page of Jewish history.

But the battle in the Warsaw Ghetto is destined to be more than this. It will not only be a page in the history of the Jewish people.

There have been many battles that astound human memory through their scale, through the complexity with which they were planned, through the brilliance with which these plans were executed; there have been many battles in which military historians, armies, nations, and states take pride. But there are battles more significant than Cannae, the Trojan War, and the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, battles more significant than Trafalgar, Austerlitz, and Verdun. These infinitely more important battles are the battles for human freedom—such battles [and pride in them] are not the possession of a single state and nation; they are the possession of [laboring] humanity. Their lesson is eternal. [Such battles are the uprising of Roman slaves led by Spartacus, the battle of the Paris Commune, and the Battle of Stalingrad.] The Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto will take its place among these [such] battles for human freedom and dignity. Soldiers of the Warsaw Ghetto! You stand in the ranks of the immortals! You are as immortal as freedom is immortal.

From Dispatches From the Frontline by Vasily Grossman. Forthcoming in English from New York Review Books. Translation Copyright ©2024 by Robert Chandler

Suggested Reading

Shifting Daylight

Ross shows how the U.S.-Israel relationship has survived, and even thrived, since 1948 despite the radically different approaches taken by successive presidents.

Re-Intoxicated by God

The way out is clearly marked: Intense Talmud study leads to intense study of science and philosophy. Spinoza was (in fact, sometimes still is) a crucial step along the path out.

Lost in Translation: Song of Songs and Passover

Why is this Targum different from all other Targums?

Portrait of an Artist “Like Buttah”

If anything ties Barbra Streisand's new memoir together, it's the author's intense need for control.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In