Shifting Daylight

Over the past 35 years, no American has been more deeply engaged in the Sisyphean task of trying to foster peace between Israel and the Palestinians than Dennis Ross. From the time he joined the Carter administration as an assistant to then Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz until midway through the Obama administration, Ross held a series of high-level Middle East policy positions in the White House or State Department under every president except George W. Bush. And during the tenures of Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, Ross was the point man for the United States on what has dubiously enough become known as the “peace process.” Now, from his on-again, off-again perch at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Ross has undertaken the task of summing up the history of U.S.-Israel relations from Truman to Obama.

Although Ross’s book is titled Doomed to Succeed: The U.S.-Israel Relationship from Truman to Obama, he could also have called it Groundhog Day. Ross quotes fellow historian-diplomat Stephen Sestanovich as saying that every president since World War II entered office believing that “the world had changed in some fundamental way that his predecessor either totally misunderstood or failed to manage effectively.” They also came into office with a new playbook for the Middle East. Devoting one chapter to each administration since Truman, Ross shows how the U.S.-Israel relationship has survived, and even thrived since 1948, despite this. In doing so, he also describes how “a number of interrelated assumptions about Israel and the region have embedded themselves in at least part of the national security apparatus—and frequently informed presidents.” These ideas, which largely emanate from Foggy Bottom, include “the need to distance from Israel to gain Arab responsiveness, concern about the high costs of cooperating with the Israelis, and the belief that resolving the Palestinian problem is the key to improving the U.S. position in the region.”

Ross convincingly argues that this approach is “fundamentally flawed” and highlights the presidents who rejected it most forcefully: Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. He is also surprisingly unsparing in his criticism of his most recent boss, President Obama, who, Ross makes clear, unequivocally accepts the State Department’s traditional view of Israel.

Ross begins his tour of U.S.-Israel relations with Truman, who has long been regarded as a hero in the pro-Israel community because of his support, over the strong objection of his State Department, for the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan, as well as for his courageous recognition of the State of Israel only hours after it declared its independence. When Truman’s secretary of state, the illustrious George Marshall, warned him that, “If the President were to follow Mr. Clifford’s advice [in favor of recognition] and if in the election I were to vote, I would vote against the President,” Truman ignored him. However, despite Truman’s genuine support for the Zionist cause (which largely stemmed from his desire to help the victims of the Holocaust find a refuge), once Israel came into existence, he followed his State Department’s advice and kept assistance to Israel to a bare minimum. Indeed, during Israel’s nearly year-long War of Independence, the United States enforced an arms embargo on Israel and its adversaries.

The Truman State Department’s stance was predicated on the idea that support for Israel would be disastrous for U.S. interests in the region, an idea that, as Ross shows, periodically finds its way back into the mainstream of U.S. foreign policy, despite the lack of evidence to support it. Two of Truman’s senior advisors, George Kennan and Loy Henderson, predicted that the U.S. would lose access to Arab oil; would drive the Arabs into the embrace of the Soviets; and would end up spilling its own soldiers’ blood on behalf of the Jews, because otherwise they would surely be defeated. Ross is at his best debunking the positions of the State Department’s Arabists, showing that none of their dire predictions ever came true. First, the Saudis’ economic interests in selling oil to the U.S. trumped whatever animus they may have felt toward the U.S. In fact, King Saud actually increased cooperation with the U.S. after Truman recognized Israel. Second, there is absolutely no evidence that greater U.S. support for Israel would have driven the Arabs into the Soviets’ arms. After all, despite the Soviet Union’s extensive provision of munitions to Israel during Israel’s War of Independence (through their proxy Czechoslovakia), the Arabs weren’t alienated from the Soviets. And third, Israel proved itself capable of defeating simultaneous attacks from Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt without any American military support.

As Ross shows, U.S.-Israel relations have followed a predictable pattern, with each newly elected president feeling the need to change the country’s Israel policy because of a view that his predecessor got it wrong. Thus, believing that Truman’s support for Israel was motivated by electoral considerations, Eisenhower decided to distance the U.S. from Israel. Conversely, when Kennedy was elected, he strove for warmer relations with Israel, both because he saw it as a country with which the U.S. shared basic values and because, as he told David Ben-Gurion, “I was elected by the Jews of New York,” whose favor he wished to repay. This pattern has continued, with Johnson, Clinton, and George W. Bush fostering warmer relations with Israel and Nixon, Carter, George H.W. Bush, and Barack Obama all coming into office intent on putting more distance between America and its ally.

Ross’s overarching historical argument is that, in fact, American interests in the region have suffered whenever the U.S. pulls away from Israel. “Not only was there never a benefit” from such policies, he concludes, but “in many cases our relations with Arab States worsened.” He cites the Eisenhower, Nixon, and Obama administrations as key examples of periods during which our standing in the Arab world fell, notwithstanding the effort each of these presidents made to be more “neutral” in their approach to Israel than their predecessors. For instance, when Nixon’s first secretary of state, William Rogers, tried to peddle a plan that would have returned virtually all of the Arab territory captured in 1967 without addressing Israeli security needs, the Arabs “rejected our outreach and actually drew closer to Moscow.” Moreover, Ross points out that such American coolness toward Israel actually discouraged the Arabs from making peace with it: “Every administration that distanced from Israel succeeded only in building expectations of what more we might do to accommodate Arab interests, not what Arab leaders might do in response to our distancing.”

The corollary to Ross’s argument, as he also makes clear, is that those administrations that avoid allowing too much daylight to come between the U.S. and Israel are much better equipped to promote the peace process. Rejecting the traditional State Department advice, both Clinton and George W. Bush, in particular, understood that only when Israel truly feels secure in its relationship with the U.S. is it willing to take risks. This was certainly borne out during the waning days of the Clinton presidency when Prime Minister Ehud Barak made an unprecedented offer to withdraw from nearly all of the territory captured by Israel in 1967 and during the George W. Bush presidency when Prime Minister Ariel Sharon handed over the Gaza Strip to the Palestinians—the first Israeli withdrawal from territory since the 1970s. In what was clearly a premeditated effort to reassure Sharon that the U.S. had his back, Bush told the press that he “believe[d] that Ariel Sharon is a man of peace,” even as Sharon’s military was holding Yasser Arafat under de facto house arrest in Ramallah. As National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley observed, Bush “had a ‘gut feeling’ for leaders and how you invest in them so they will respond to you.”

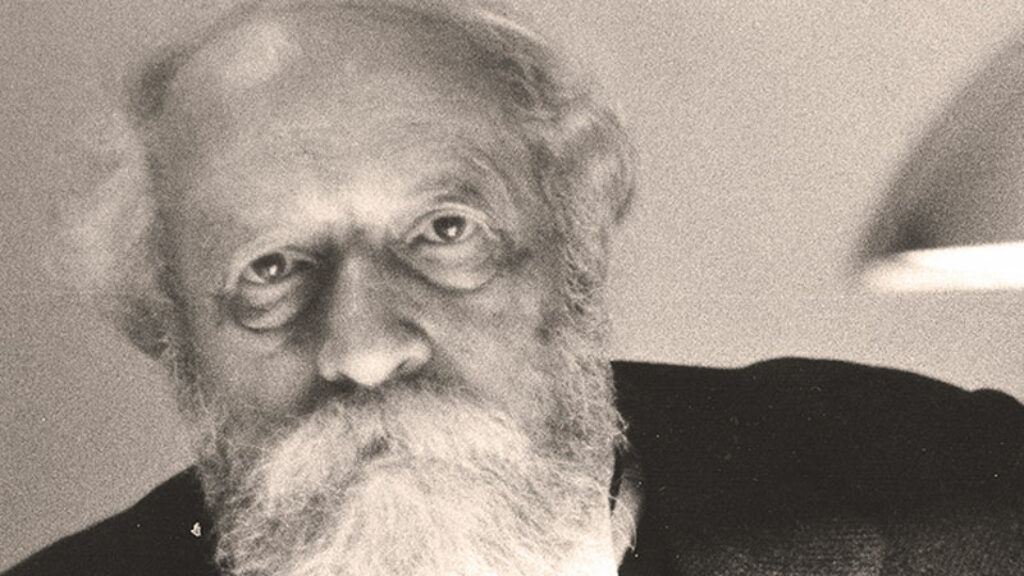

Ehud Barak meet in the West Bank town of Ramallah, March 8, 2000, in a second attempt

to regenerate the Israeli-Palestinan peace talks. (AWAD AWAD/AFP/Getty Images.)

In sharp contrast to Clinton and Bush, President Obama came into office, Ross writes, “believing that we needed to distance ourselves from Israel.” In a telling anecdote from the early days of the administration, Ross describes how his suggestion that Obama combine his initial trip to Cairo, where he planned to give his first major foreign policy address, with a visit to Israel, was rejected. As Ross notes, Obama wanted to advertise that “[he] was different, and the Muslims needed to see he was different.”

And different he has been. Ross explains that even though President Obama “had an instinctive commitment to Israel’s security” and “always responded to Israel’s security needs,” “[h]is instinct to see the Palestinians as the victims in the conflict remained too strong” for him to contemplate an “uncritical embrace” of Israel. Thus, in 2014, when Obama urged the Israelis to see Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, also known by his nom de guerre Abu Mazen, as a viable peace partner, Obama “said nothing about what Abu Mazen had to do; the responsibility for acting was exclusively Netanyahu’s.” Moreover, when Abbas simply refused to respond to Obama’s proposal for an agreement that had not even been cleared with Israel (including a provision that Jerusalem would have two capitals for two states), Obama “gave him a pass by blaming his ‘shutdown’ on Israeli settlement policy.”

As Ross shows again and again, the State Department’s focus on trying to distance the U.S. from Israel actually disincentivized the Palestinians from making compromises for the sake of peace. But he implicitly hints at another, potentially far more troubling by-product of that policy. In the preface to the book, Ross describes a conversation among President Obama and the leaders of three of our most important allies: England, Germany, and France. Even though the agenda for the meeting didn’t include Israel, all three leaders—David Cameron, Angela Merkel, and Nicolas Sarkozy—launched into spontaneous tirades against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, calling him a liar and the obstacle to peace. One wonders if this should be taken merely as an indication of how tenuous Europe’s relations with Israel really are, or whether the comments about Netanyahu were encouraged by the leaders’ perception of the Obama administration’s own animosity toward Israel.

If there is one other message Ross wants to impart to future occupants of the White House, it is that the United States should pay more attention to the genuine interests of the Arab countries. As Ross writes, “The point is not that the Palestinians don’t matter. They do. But the hard truth is that they are not a priority for Arab leaders . . . The priorities of Arab leaders revolve around survival and security.” Ross illustrates the danger to regional stability that can result from a vacillating America with a story from the Suez Crisis. President Eisenhower strongly opposed the military

action taken by Israel, Great Britain, and France after Nasser blocked the Suez Canal in 1956, arguing that the United States “had a duty to oppose aggression.” As Ross puts it, “What damaged the United States was the perception that it would not stand by its friends.” In fact, when Lebanon’s prime minister visited the White House in 1959, he told Eisenhower that “U.S. behavior during the Suez conflict had led him to believe that America would never ‘resort to force to support friends.’”

In view of all the years Ross has toiled in the largely barren fields of the peace process, it is notable that his book is short on policy prescriptions for the key protagonists in the conflict. In fact, notwithstanding his criticism of Obama for giving Abu Mazen a blank check, Ross says very little about what the Palestinians need to do to achieve their goal of statehood. His one real policy suggestion is directed toward Israel. Specifically, Ross writes that the Israelis

should declare that they will negotiate on borders with the Palestinians, but until it is agreed upon, they will build only in those areas that they think will be part of Israel: to the west of the security barrier and the existing Jewish neighborhoods in Jerusalem.

No doubt most Israelis would happily walk away from most of the territory captured in 1967. Many would even be willing to make some accommodations in parts of east Jerusalem (defensive barriers are now being built to isolate the Arab neighborhoods in east Jerusalem in the wake of the knife attacks). But at a time when the Palestinians seem to have abandoned any desire for a two-state solution, it is simply unrealistic for any Israeli government to halt all settlement activity in the West Bank, especially given the organic growth taking place within those communities.

But the larger problem with Ross’s suggestion is that it falls into one of the traps that he himself has just spent hundreds of pages criticizing—the notion that U.S. policy is a matter of pressuring Israel. Notably, the one president who bucked that trend was George W. Bush, for whom Ross didn’t work. As Ross notes, Bush was “breaking the mold” in trying to empower the Palestinians while also holding them accountable for their conduct. Thus, he “offered full-throated U.S. support for the creation of a state” and told the Palestinians from the Rose Garden in a speech on June 24, 2002: “You deserve democracy and the rule of law. You deserve an open society and a thriving economy. You deserve a life of hope for your children. An end to occupation and a peaceful democratic Palestinian state may seem distant, but America and our partners throughout the world stand ready to help . . .” But Bush also made clear such a state could only emerge if “Palestinians embrace democracy, confront corruption and firmly reject terror.” It would not come about solely as the result of territorial concessions by Israel. In other words, U.S. policy should not simply be to promote land for peace.

Despite his sober analysis of 65 years of negotiations between Arabs and Israelis and, in particular, the utter failure to achieve peace between Israel and the Palestinians since the 1967 war, Ross is not prepared to give up entirely on the peace process—though he readily acknowledges that “it would not be a game changer in the region.” Maybe you can take the man out of the peace process, but, after all those years of negotiating for peace, you cannot take the peace process out of the man. Nevertheless, Ross has written an illuminating history, and his detailed accounts of the behind-the-scenes policymaking in the halls of the White House, the Situation Room, and the prime minister’s residence make for fascinating reading for anyone with an interest in America’s policy in the Middle East. One hopes that his book will become required reading for those in the State Department and the National Security Council who are charged with making that policy.

Suggested Reading

Letters, Spring 2023

Cliff-Hangers When I first read Hillel Halkin’s assertion in “On That Distant Day” (Winter 2023) that “for years now, Israel has seemed to me like a man sleepwalking toward a cliff” and “now we’ve fallen from it,” I thought it was excessive, though I shared his concerns about the Likud’s coalition partners (Zionist theocrats, anti-Zionist free-riders). Writing now, in the…

Silence of the Lambs

Sacrifice is both foreign and familiar. Actually sacrificing an animal is difficult to imagine, and yet we continue to speak freely of sacrifice in connection with political and moral obligations.

History with a Flourish

So much gets lost in translation—and to history—when household items, heavy with use, first assume the status of heirlooms and then land in museum vitrines, heralded as art rather than history.

A Life of Dialogue

Martin Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their heritage with a vision of Judaism they could identify with.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In