Unsettling Ideology

Irving Howe once told me that the purpose of a polemic is to kill your opponent—with words, not knives; still, at the end, the opponent should be politically, intellectually finished. But you can’t kill an ideology (as Israeli generals have recently told us), so Adam Kirsch’s beautifully argued critique of the new understanding of “settler colonialism” isn’t designed to kill the idea but rather to show that the politics it inspires will end (has ended) in destruction and death. His critique is calm and careful, but it is also smart, sustained, and fierce. And then at the end, Kirsch gives his readers a moment of grace and the possibility of reconciliation.

Settler colonialism as an actual historical process is indeed a tale of destruction and death as settlers from Europe displaced and sometimes replaced the native populations of their countries’ colonies. The process is well worth studying (and even theorizing) since it has happened again and again in world history. You could say that conquest, settlement, destruction, and death are history’s dominant themes. It turns out, as Kirsch says, that all the indigenous people were once settlers themselves: “Every people that occupies a territory took it from another people, who took it from someone else.” Each moment of conquest and settlement is a moment of cruelty on the one hand and suffering on the other. So we need both a historical account and critical reflection on settler colonialism.

But do we also need the militant new ideology that mobilizes opposition to settler colonialism, broadly and ahistorically construed? Certainly, we must understand it. As Kirsch writes, “The term encapsulates a whole series of ideological convictions—about Israel and Palestine, but also about US history and many social and political issues, from the environment to gender to capitalism.”

This ideology originated in the academy, though much of the academic work was ideological from the beginning—calling for a political project. Something like that project was anticipated in places like post–World War II Algeria, where the colonial settlers did not replace the native population (which included both long established Berbers and their Arab conquerors, now indigenous together). Instead, a dominant minority of European settlers, the pieds noirs, ruled over an Algerian majority. So the struggle against the settlers had a fairly democratic character: the goal was popular sovereignty or, since the majority identified itself as a nation, national liberation. The struggle was brutal on both sides, and it ended with decolonization—the forced departure of the settlers, back to France, the country that had promoted and protected the settlement.

The case of the United States (not to speak of Australia, Canada, etc.) is obviously different, and here radical settler colonial ideology gets tricky. Settlement was a long-term process that virtually eliminated the Native Americans, and the settlers’ descendants now make up something like 97 percent of the population. So there can’t possibly be a democratic struggle against them; there certainly can’t be a forced departure. There could be—in fact has been—a liberal struggle for minority rights, but the new ideological militants aren’t interested in that. Indeed, the establishment of a truly liberal regime, with civil rights for everyone, would be a monumental defeat for the theorists of settler colonialism. For it would mean that the remaining Native Americans had assimilated into the political culture of the settlers, accepting the crumbs of citizenship, giving up on the feast of sovereignty. “A struggle for equal citizenship,” writes Columbia anthropologist Mahmood Mamdani, “looks like a masked acceptance of final defeat: total colonization.”

So equality is rejected, and then what? Much of Kirsch’s book is an effort to describe the strangeness of the militants’ politics and to expose the implicit, sometimes explicit, cruelty of their ideological commitment to decolonization. His account of their program for the United States is a revelation even to political obsessives like me. Who knew about the necessary “relinquishing of settler futurity”?

What that means, it turns out, is that only the Native Americans deserve a future. What twentieth-century American leftist ever imagined, as Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang insist in a 2012 paper titled “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” that justice requires a process that “would impoverish, not enrich, the 99%+ settler population of the US”?

Decolonization is the political opposite of Occupy Wall Street’s project for the 99 percent. It is in fact a zero-sum game, in which, Kirsch explains, “Natives win (land, sovereignty, power) only if settlers [that is, the rest of us] lose.” But how to bring about that loss? I have already suggested the magnitude of the problem: there are well over three hundred million Americans whom theorists like Tuck and Yang classify as settlers. According to the theory, settlement isn’t something that happened in the past; it is happening right now, and all of “us” are involved: “Invasion is a structure, not an event.” This line from the Australian historian Patrick Wolfe is, Kirsch writes, the central maxim of settler colonial ideology. All of us settlers inhabit the structure and enjoy the advantages it brings.

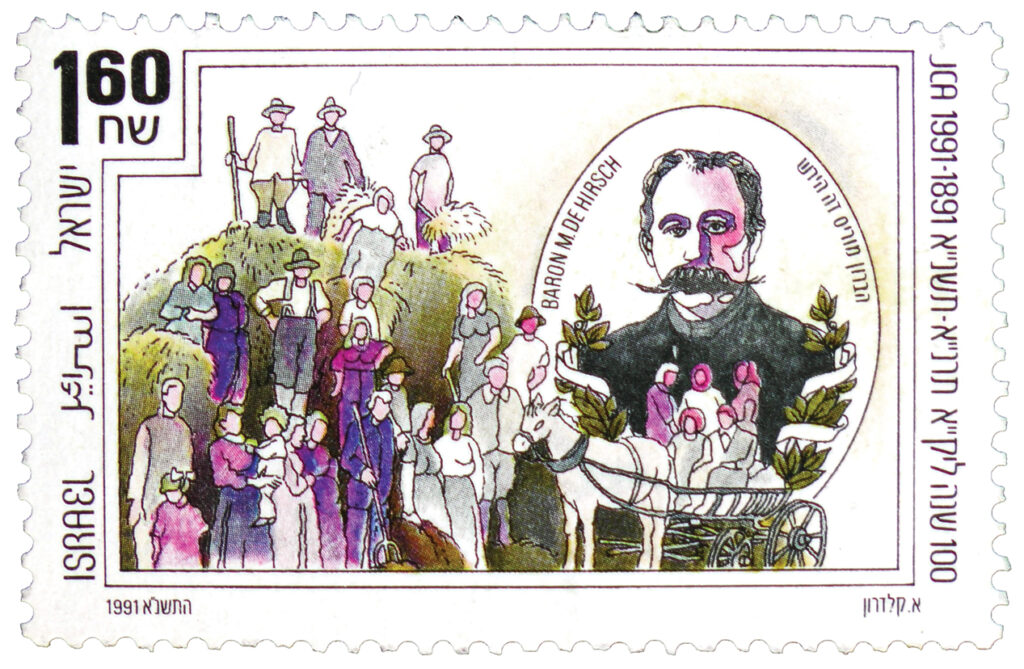

So I am a settler, though my grandparents arrived almost three hundred years after the Puritans landed in New England. My maternal grandfather is especially blameworthy, since he “settled” on a farm in Connecticut (with the help of Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a sponsor of poor Jews from Eastern Europe) on land that belonged, and will always belong, to one of the Native American nations. Black slaves, indigenous in Africa, became settlers when they were brought here, even though they were brought against their will. Slaves as settlers, as a friend remarked to me, sounds like “a category error.” But according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which adheres to the new ideology, Black Americans “benefit from the settler-colonial system as it stands today.” They, too, are implicated in the structure.

What is to be done? Kirsch’s effort to find an answer to that question in the sometimes brutal but always elusive literature of the militants is heroic. In principle, they want all the settlers, all of us, to be gone, or to cede sovereignty to the Native American nations (and live, presumably, as their subjects). As Kirsch sums up a key text: “America is something that should not have happened.” Calls to “eradicate,” “kill,” or “cull” the settlers are, Kirsch remarks, “only metaphorical, so there is no need to put a limit on their rhetorical ferocity.” The ferocity is ever present, often accompanied by quotes from the Algerian writer Frantz Fanon, which give it a realistic touch. But since there really is nothing to be done, a radical critique of “settler ways of being” is the actual politics of the militants here in the US.

Colonization Society, circa 1991. (Courtesy of Alexander Mitrofanov/Alamy Stock Photo.)

Their aim, Kirsch writes, “is to deconstruct the social order founded by settler colonialism.” This “founding” is entirely different from the standard accounts of the American founding. It is not the birth of liberty but rather the origin and cause of everything that is wrong in the US: “racism, white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, and capitalism”— that’s the short list; environmental degradation is the most common addition. As Kirsch dryly notes, how any of these evils occurs in countries without a known history of settler colonialism is a mystery.

The greatest evil is genocide—which, like settlement, is not confined to what we used to call colonial history; it is an ongoing process, begun by the original settlers and continued by their heirs. Pretty much everything that today’s settlers do—that we do—is effectively genocidal. Even efforts at reconciliation, writes Lorenzo Veracini, contribute to “the extinction of otherwise irreducible forms of alterity.” The examples of cultural and material genocide that militant theorists provide—the creation of national parks, industrial farming, the offer of citizenship and equality—suggest how easy it is to define genocide down. Mockery seems the obvious response to those who would put Yosemite in the same category as Auschwitz, but the argument about genocide gets uglier when its focus shifts from the United States to Israel.

Since the ideology of settler colonialism demands a politics that can’t be acted out, at least not in the US, it is best understood, Kirsch argues, as a political theology. Here I will have to simplify an especially rich analysis. Settlement is the original sin, or, better, the settlers’ insatiable desire for more land, more wealth, more power is the original sin. All the evils of exploitation, racism, misogyny, and homophobia follow from the everlasting settler moment. Redemption comes only with decolonization: some secular mix of a return to Eden and the advent of the messianic age.

The picture of life before settlement is idyllic. The Native Americans lived in a society of equals, at peace with their neighbors, at home in the natural world. They understood the cues that nature provides for a harmonious life. Exactly what comes after decolonization is harder to describe. The world will be idyllic again, transformed, much as it might be after the messiah comes or after the Communist revolution.

Kirsch repeatedly, and rightly, compares settler colonialism to other radical ideologies that attribute “many different varieties of injustice to the same abstraction and promises that slaying this dragon will end them all.” But what, concretely, are the Native Americans to do with the settlers (or the messianists with the nonbelievers, or the revolutionary vanguard with the bourgeoisie)? “Lack of imagination also indicates lack of commitment to figure it out,” according to Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, a longtime activist and ethnic studies professor emeritus at California State University.

All the world is not America, and there is one country where “figuring it out” is easy. Kirsch doesn’t get to Israel and Palestine until halfway through his book, though the brief introductory chapter makes it clear that this is where his argument is going—an argument made necessary by the response of American progressives to October 7 (“What did you think decolonization meant?” many tweeted and posted in the days after). For many leftists, not only in the US, Israel is the exemplary settler colonial state and the Palestinians are the prime example of a colonized people. This is a view of the conflict that misses most of its history—or, better, it is an ideological construction of the conflict that takes little interest in history.

But it is important to acknowledge (as Kirsch never quite does) that Israeli settlement on the West Bank from 1967 until the present moment fits the ideological construction all too neatly. The settlers aim to expand Israeli territory; they aim at the subjugation and, many of them, at the expulsion, of the Palestinian inhabitants; and they are protected by the Israeli state, from whose territory they come. Their militants are driven by a theological version of manifest destiny. And it is entirely possible to imagine, though at this moment it isn’t likely, a return of the settlers to the homeland on the other side of the Green Line—like the return of the pieds noirs to France.

This account of West Bank settlement actually proves, by contrast, the falseness of the settler colonial account of Israel itself. The Zionist settlers in Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine, and in the new state after 1948, were desperate refugees, fleeing persecution, hoping initially to live side by side with the Arab inhabitants; they did not have the sponsorship or protection of any of the states from which they came—most of which had a long history of antisemitism. There was no country in the world ready to take them back or take them in. Nor was Jewish settlement in Palestine a European invasion; half or more of the settlers fled from Arab countries.

The flight and expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Arabs in 1947–1948 came during and after a war that the Jewish settlers didn’t start, and the 150,000 Arabs who remained in Israel in 1948 have now grown to around two million, which is not the usual effect of genocide. Of course, according to the ideology of settler colonialism, Arab citizenship in democratic Israel is itself effectively genocidal—a loss of rightful sovereignty, a cancellation of alterity. Today, the number of Arabs and Jews living “between the river and the sea” is roughly even: some seven million each. This is nothing like America; there actually is room and people enough for two sovereignties. What the militants want, however, is for Israeli Jews to “relinquish their futurity.”

“Israel is much younger and smaller than the United States,” Kirsch writes, “and it is easier to imagine its disappearance.” Similarly, the number of Jews, all of them defined as “settlers,” is small enough to allow the antisettler militants to plan their subjugation, exile, or elimination. The leading ideologues argue only for the end of Jewish sovereignty; what comes after that is, as usual, more vaguely described. But Kirsch, who has read more extensively in the literature of settler colonialism than anyone I know would willingly do, concludes that its effect is “to cultivate hatred of those designated as settlers and to inspire hope for their disappearance.” Israel is accused of genocide—and threatened with genocide.

So the radical theory of settler colonialism became “the theory of a massacre,” the ideology that justified Hamas’s atrocities of October 7 and inspired the response of too many American professors, students, and activists. The Israeli settlers were taken to be rapacious and domineering; the native Palestinians were innocent and oppressed, and October 7 was an exhilarating example of a struggle for liberation, as a Cornell historian infamously told rallying students.

To be sure, the Hamas terrorists were not killing and raping to oppose settler colonialism; they acted for religious reasons—they were zealots whose goal was the elimination of any Jewish presence in what they regard as Muslim territory. The ideology of the antisettler militants is entirely secular, but it serves to justify theologically driven rape and murder. I wonder how many of the student protesters who thought they were opposing settler colonists understood what they were defending. Kirsch writes, I believe, first of all for these young men and women, to convince them that an ideology that “makes violence virtuous” needs to be reconsidered.

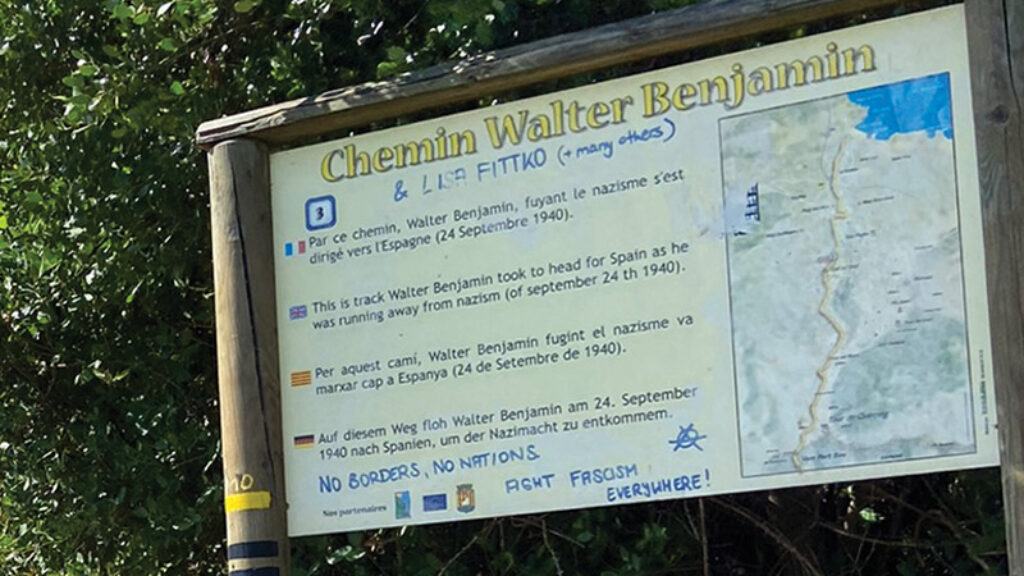

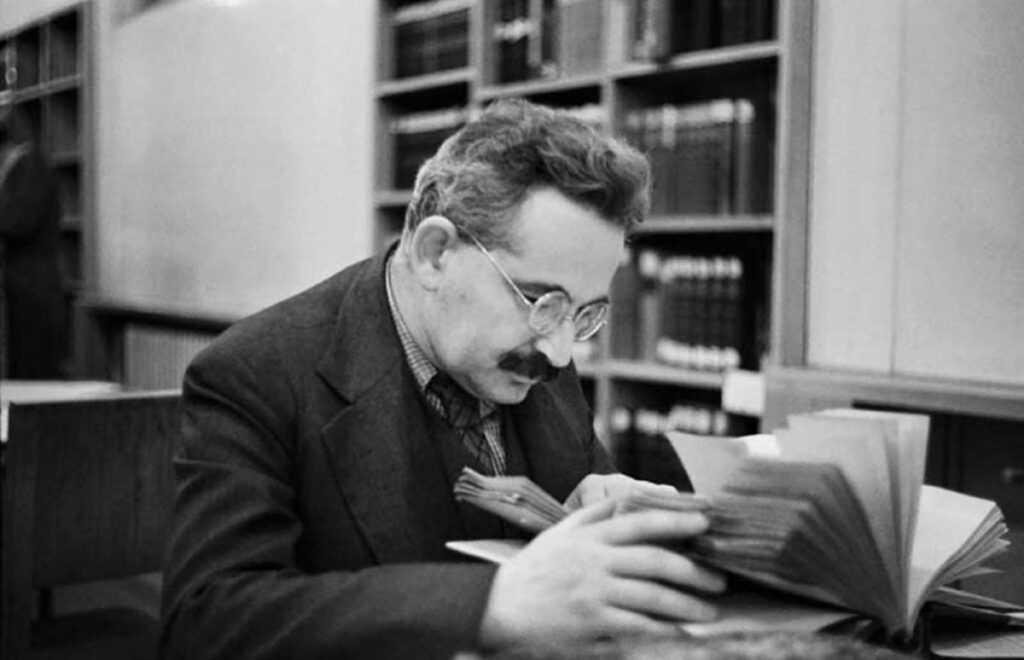

The tone of Kirsch’s last chapter, “Justice and Despair,” is different than the rest of the book. It is a meditation on what Walter Benjamin called “the tradition of the oppressed.” For Benjamin, oppression is ever present, and our duty is to recognize it, to “call in question every victory, past and present, of the rulers” by seeing them through the eyes of the oppressed. Beyond that, beyond reading history against the progressivist grain, Benjamin had no plausible politics. His moment was a moment of hopelessness. “The only way he could envision redemption,” Kirsch writes, “was as the cancellation of history.”

Settler colonial ideology shares a similar bleakness—America, and Israel, should never have happened. But it also pretends to have a political response. Kirsch acknowledges that “there is not a single country whose history does not provoke horror, if seen through the eyes of the victims rather than the victors,” but he rejects the millennialism of the militants. History cannot be undone. Israel’s disappearance is indeed easier to imagine than America’s, “but again, not without massive death and destruction.” There has to be another way to think about, and to deal with, the horrors of history.

Kirsch invokes a talmudic principle developed in response to certain kinds of property dispute. Imagine a stolen garment that is sold to a merchant and then bought by a customer. Does the original owner have a claim, given that the customer acted in good faith? The law assumes that the original owner has “despaired” of the garment; he or she is entitled to compensation and damages, but the garment now belongs to the person who bought it. “Is despair justice?” Kirsch asks, “No. It is what the law offers instead of justice, knowing that perfect justice often cannot be achieved.”

Think about land in a similar way: perfect justice, Kirsch argues, would mean restoring the Land of Israel to the Jews who were driven out of it by the Romans and also to the Palestinian Arabs who have been denied sovereignty by the Jews. “But any attempt to secure the country for just one of these peoples would inflict suffering on millions whose only sin was being born in a contested land.” Despair over past losses would make it possible to hope for a better future for both peoples: “The creation of the State of Israel should not be negated, but Palestinians should have the security and dignity of their own homeland.”

I doubt that either Hamas’s Islamists or Jewish messianists would find this kind of despair acceptable. But Kirsch’s argument, at once sharp and conciliatory, points the way toward more serious scholarship about settler colonialism, toward an intelligent reflection on the pain it has caused, and toward a politics of imperfect justice and peace.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Protocols of Neoliberalism

Baram’s characters are righteously indignant at the system and determined to bring it down.

The Christian Road to Jerusalem

Looking back on the clash of civilizations.

The (Railroad) Baron

How the man who built the Orient Express lost track of his legacy.

Walking with Walter Benjamin

On losing one’s self in Walter Benjamin’s final wanderings.

vernue

Which came first: anti settler colonialism or anti-zionist antisemitism?

That’s a broader question than I can’t address in a response letter, but after a point, it seems like antisemitism is being shoe-horned into a convenient ideological neo-Marxist boot. People who we call intellectuals (because they use big words? Because they teach at universities?) create or mold ideologies to fit their pre-exiting prejudices. It is fun and easy and presented with the authority of an intellectual using big words or legitimized by a university position.

I find it incomprehensible though how Walzer can distinguish between the legitimate colonization of inside-the-Green-Line Israel and what he calls Israeli settlements in the West Bank, which he thinks precisely fit the bill of a settler colonialist regime. He seems to ground the legitimacy of the present-day state of Israel upon their colonization and expulsion by the Romans 2000 years ago, followed by the genocidal colonization of the Catholic Church and subsequently the Moslem Arab conquest and ethnic cleansing of the 7th century. If so, he recognizes that long term residency of an area confers, if not indigenous status to a people, then at least a claim of legitimacy to their occupation. As backed up by both archaeological and historical record, Jewish settlement of the land of Israel was rooted in those areas Walzer calls the “West Bank.” Possession of those lands in modern times are a result of a defensive war thrust upon Israel and continued possession of those lands are of undeniable military importance.

The desire of Jews to inhabit the lands of their ancestors is anything but settler colonialist.

Walzer’s characterization of Israelis living in those areas is absurd, as he probably knows. In any case, it does not undermine the fundamental argument; Jews are returning to their ancestral homeland. According to Walzer’s analysis, they should be seen as having rights there, although perhaps not exclusive rights. Since it is the Jews - even Jews of Yehuda and Shomron - who are in the main pursuing peace and the Arabs who are pursuing genocide, there is a moral argument to be made for supporting continued and even expanding Jewish settlement in these areas, as it increases overall security, both for Jews and moderate Arabs.

I live in the village of Shilo, above an archaeological site of the same name that was once the first capital of the tribes of Israel in our land. I have no desire “to genocide” the Arabs who live across the valley, not economically or culturally or demographically, except to the extant that my neighbors and I will defend our rights to our land. Like most of my community, I would welcome friendly relations with local Arabs, though establishing trust would be a challenge. I find it difficult to see how Prof. Walzer could point to me as an example of a settler-colonialist. But he’s an intellectual, so I’m sure he can shoe-horn me in.